The earliest days of company-building are typically a solitary slog, an exercise in delayed gratification. It’s just you, maybe a co-founder and a few early hires, coding and running cold outreach for hours on end. Even with a newly minted product and a handful of customers, it’s tough to zoom out from the grind and figure out whether you’re making good progress in those first few months (and even years).

You might be stuck in a loop of self-doubt, asking yourself, “Is our message landing? Do people actually like — and use — what we’ve created? Is this what product-market fit is supposed to feel like?”

From a quantitative lens, there are metrics to lean on as you seek to answer those questions, from ARR to CAC to sales conversions. We’re big fans of taking a more scientific approach to finding PMF here at First Round — it’s why we launched PMF Method and published detailed benchmarks B2B SaaS startups should be aiming for in our analysis of the four levels of PMF, alongside actual data from Looker’s trajectory through these stages.

But numbers aren't the only signals to monitor obsessively, especially when it’s still early and you can’t even calculate some of these figures yet. In the opening stretch of a startup’s life, you can’t write off the subtler qualitative cues entirely.

The rub is that the non-numerical leading indicators are easy to miss in the swirl of startup life. And in some cases, they might even feel the opposite of promising in the moment — like a deluge of customer complaints or an uptick of competitors tackling the same problem. Sparks of traction are often easier to clock in the rearview mirror.

Eilon Reshef, CPO and co-founder of Gong, puts it this way: “As a founder, I was always looking for the negative signs instead of the positive signs. Focusing on what you can improve isn’t a bad idea, but then you’re never in celebration mode.”

So we revisited the conversations we’ve had with founders in our paths to PMF series, digging deeper into the stories of their messy early days to surface the most surprising moments when they knew things were working — even if it took years of hindsight to recognize them. These glimmers of potential were hard-won, often appearing after painstaking periods of pivoting, refining the message and bouncing between ICPs.

Before you have hard numbers or encouraging trend lines, watch for the following signals from your customers, your industry, your competition — and even your own mindset. Hopefully, these stories from fellow founders who’ve been in the trenches can help you spot these signs in real time — and serve as a welcome affirmation that pushes you to keep chugging along.

HOW YOUR CUSTOMERS FEEL

Criticism is better than crickets

The obvious gauge for customer satisfaction is usually a high NPS or low churn rate — or per Sean Ellis’ classic benchmark (featured in the popular PMF framework from Superhuman’s Rahul Vohra), how disappointed customers would be if they couldn’t use your product anymore.

But some of the founders we spoke to found that complaints are an underrated (and counterintuitive) measure of customer love. Consider it the customer version of radical candor — if they’re giving you honest feedback, it means they actually care. If customers aren’t saying anything at all, there’s a good chance they don’t.

Just ask Eddy Lu, GOAT’s CEO and co-founder. After a period of sluggish sales in the months following the sneaker resale site’s launch, his team wanted to do a Black Friday promo to drum up more interest. But after building some hype with features in all the industry publications, on the day of, an influx of users crashed the website, and thousands of people eager for an ultra-discounted shoe walked away empty-handed — and took to social media to curse out Lu.

While that was no doubt a hellish experience, Lu managed to find the silver lining: GOAT had found an upswell of consumer demand. “In that painful moment, we got advice that I’ll always remember: At our company’s stage, it’s better to be hated than unknown,” remembers Lu.

Read more about how Lu pivoted from cream puffs to iPhone apps before landing on the billion-dollar idea that became GOAT.

Eilon Reshef had a similar brush with customer criticism — albeit a more tame version.

Back when he was working on the beta for Gong, which was conceived as a tool that records sales conversations with prospects, he and his co-founder tested the product with a batch of design partners. After the design partners had been using it for a few months, Reshef started getting tons of complaints.

“Our design partners started telling us, ‘How come you didn’t record this call?’ Which is ironic because Amit’s vision for Gong was just to record some of the calls and do the analytics from there, and it’ll work the same way. But it turns out sellers and managers were like, ‘I’m relying on this tool to be my eyes and ears and notepad for all of my calls,’” says Reshef.

“Getting so many complaints about our system not recording all calls, which it wasn’t even designed to do, should have given us better indication that it was becoming a critical tool versus just a nice-to-have.”

All 12 of Gong’s first design partners eventually converted into paying customers — another early signal that they’d built something people wanted.

Criticism is better than people ignoring you, which means they probably don't need your product. If people start complaining, that's usually a good sign.

Get more of Reshef’s learnings about leaning on design partners and non-obvious signs of product-market fit.

Strangers are willing to try your product

If complaints are being hurled at your startup, they’re probably from people you don’t know. By the same token, if you ask your friends to be early users of your product, they’ll most likely oblige out of generosity, not from an actual need.

That’s why Sprig co-founder and CEO Ryan Glasgow likes to assess a product’s stickiness by how many people respond to cold pitches during customer development. In the realm of B2B selling especially, acquiring customers through your personal network can give you false positives with product-market fit.

“One of the key learnings I had early on is to never involve people who you personally know in the customer development process. Folks often reach out to their own audience for customer development — but I think it’s often misleading. Instead, I started to cold email founders and PMs at Y Combinator companies. I had no relationship with them, and I wanted to see if they would respond to my emails, because if I'm truly solving a pain that they're experiencing, then they will spend time. And I was able to get several of them to respond and take meetings with me,” says Glasgow.

In B2B, time is more valuable than money if you're selling to someone here, because it's the company's money, but it's their individual time. And they're often very busy with a lot of different priorities.

Read more about the product hurdles Glasgow overcame to spring from MVP to multi-product while building Sprig.

You’re swamped with feature requests

Getting tons of asks from your customers might seem like a tell that you haven’t quite figured out what they want. But in Clay CEO and co-founder Kareem Amin’s experience, a flood of feature requests was a positive indicator.

Amin spent the first few years wrestling with whether to go wide or narrow with the product’s scope, playing around with different ICPs and positioning and struggling to commit to just one. Eventually, the Clay team decided to focus on just outbound salespeople and began molding the product’s features accordingly.

That ended up being the right call. In Amin’s view, one of the precursors to the breakout success that followed was that their customers started asking for even more features.

“Sometimes we would ship a bug and then a customer would immediately flag it,” says Amin. “This is in many ways a good thing because it means that they care and are using Clay. So once those things started to happen, it was clear that we were being pulled along and that a lot of our theses were right.”

Read more about how Amin whittled down Clay’s ICP to mold a product that finally landed.

You see your product open on customers’ screens

Securing a contract with an enterprise customer is no guarantee of actual usage of your product by its employees. You might be skeptical that the people who make up your ICP — and not just the company’s decision-makers — are getting any value out of it.

Andrew Ofstad, Airtable CEO and co-founder, had to break out of the digital realm to find out. He didn’t fully grasp that the product was taking off until he visited a newly signed customer’s office and saw people using it with his own eyes.

“We landed with WeWork and it grew virally within the company, going more or less wall-to-wall. When I was on this customer tour to New York — after having mostly interacted with customers over the support channel or Zoom — I visited the WeWork office. I looked around and everybody's computer monitor had Airtable open. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is actually a thing. People use it,’” remembers Ofstad. “It became so much more real at that point. That was the first moment when I thought we'd actually built something that might make it.”

Read how Ofstad confronted the pesky challenges of building a horizontal product.

Customers are sold on the idea alone

A few of the founders we interviewed knew their idea was a compelling one when prospects started approaching them even without a sleek website or product demo.

That was the story for Vanta. Christina Cacciopo, its CEO and founder, spent years tinkering with software that never garnered much interest, from a transcription tool to a voice assistant for biologists in labs. Finally, she landed on the idea for a security platform that helps startups get SOC 2 compliance — and she knew she’d struck a chord when people started approaching her thanks to word of mouth.

What was most impressive about that organic traction was that customers had to go out of their way to contact someone from Vanta — the team hadn’t even set up a proper website. At the time, vanta.com was only a barebones homepage with a company email address. But the team was still getting a few emails a week.

Read more about how Cacioppo validated the idea for Vanta with a minimal marketing and sales lift.

Jack Altman, former CEO and co-founder of Lattice, recalls that the first sign of real market pull was when leads started pouring in despite never interacting with the product.

That surge of demand came after pivoting away from software that helps employees with OKR planning, which the team was having a hard time selling. So Lattice switched up the product to focus performance management — and the contrast in customer interest couldn’t have been more stark. This time around, people were clamoring to sign deals even before testing out the product.

“We had people paying us annual upfront contracts without ever touching a real product, just on our design mocks — which couldn't be more different than the experience we’d been having with OKRs,” Altman says.

“There were leads coming organically from all over the place. People were telling their friends about us. People would say, ‘I'm kicking off this performance cycle in two weeks and I need this feature. You don't have it yet. Can we schedule time tomorrow to talk it through so we can help you build it?’

Once you've got something that's going to work, it's going to work even in the face of a pretty undeveloped, incomplete, semi-broken product, which we certainly had at this stage.

Find more of Altman’s lessons in pivoting to get “un-stuck” on the path to PMF in our essay.

HOW THE STARTUP COMMUNITY FEELS

No one’s roasting you on Hacker News

Nabbing the top spot on Hacker News may be an obvious spark of traction. Another less splashy but equally impressive outcome? The typical snarkfest on the dev hub subsides when you launch on it.

Michael Grinich, founder and CEO of WorkOS, took his time to build what he called a “minimum awesome product,” operating with the understanding that first impressions mean everything in the developer world.

So when he finally launched on Hacker News after over a year of quietly building, the product had a solid debut on the platform with a tagline that resonated: “Plaid for enterprise IT systems.” But what he was most proud of was that everyone had nice things to say.

“There were no snarky Hacker News comments — which is perhaps a silly metric, but I saw it as a badge of honor. Developers loved the idea of WorkOS and what we stood for,” he says. “Even though we didn't have the traditional signals around usage-based traction, I felt like we had strong product idea-market fit.”

To this day, Grinich still gets signups who reference WorkOS’ launch on Hacker News back in March 2020.

Read how Grinich spent a year quietly plugging away on a “minimum awesome product” to set the stage for WorkOS’ breakout launch.

People are calling you by your name

Naming your startup is a massively consequential early decision for founders. Love it or hate it, you’re probably saying your startup’s name so much that you’ve wrung it free of meaning in your head.

So it might not strike you as notable when you catch people in your industry name-dropping your startup. But this was a memorable moment for Shippo CEO and co-founder Laura Behrens Wu, a tangible sign that the startup had found a foothold in the shipping logistics market.

People were starting to use the name of the company, Shippo. When it’s just the two of you talking about your startup, it sounds like it's all made up and not real. But suddenly, you have other people using the name, and it feels real.

Read how Behrens Wu built an industry upstart and used her lack of experience in the shipping domain to her advantage.

Smart people are solving the same problem

There are all kinds of contradictory cliches for how to think about competition: pay close attention to it, use it as a motivating force, keep your head down and ignore it altogether.

Guillermo Rauch, CEO and founder of Vercel, has a more nuanced take on it. He’s found that sizing up the quality of your competition can actually be an indicator of product-market fit. If there are big players in the same market that make you sweat, it’s a sign that your problem is a worthwhile one to tackle.

After finding some initial traction with developers for Vercel’s open-source framework, Next.js, Rauch still wasn’t wholly convinced that it had true staying power. That was, until he heard from some respected names in the open-source world.

“Right after we released Next.js, someone from Redfin reached out saying they were building the same thing. And then a week later, someone from Trulia reached out saying they were building the same thing. These were not just folks doing little experiments. I had all these people running businesses at scale telling me that they were either building a version of this, about to assemble a team to start building a version of this or asking me to share ideas and best practices,” says Rauch.

One signal of product-market fit that I recommend you pay attention to: When something is really needed, you’ll find there are lots of very intelligent people at other organizations trying to build a version of it.

Read how Rauch materialized a childhood dream of building software into a billion-dollar open-source business.

HOW YOU FEEL

You can relax (a little)

Retool founder and CEO David Hsu struggled to know for sure whether he’d found product-market fit even despite scoring some impressive metrics, like $2 million in ARR shortly after launching. The problem was that Retool’s first customers were using the product for wildly different use cases — so he wondered whether the startup would be able to serve such a varied pool of customers.

After Retool hit around 40 customers, however, he loosened up a bit. But his outlook shift wasn’t exactly night and day.

“We talked to someone who said that finding product-market fit was so visceral that you immediately feel it — like a geyser exploding. We honestly never felt that. Every customer we got — whether that was number four or number fourteen — felt like the last customer we were ever going to find,” says Hsu.

He describes the feeling of reaching product-market fit as being able to relax a bit without worrying about the rock rolling back down the hill.

It’s like rolling a stone up a hill — if you stop pushing, it'll start rolling back down rapidly. That’s what our experience of searching for product-market fit felt like until we had a few million in ARR.

You’d use your own product

If you’re your toughest critic, then hopefully you’re a fan of what you’ve built. A few of the founders we spoke to remember their “aha” moment arriving while dogfooding their product.

That was the case for Jessica McKellar, co-founder and CTO of Pilot, a bookkeeping and tax service for startups — which her founding team had been using while they built it.

“Of course, we were using the software that we were building to close Pilot's own books. And there would be moments when the software would catch something that we had missed, like a double payment,” McKellar recalls. “And we’d realize that this wouldn't have happened unless we were using Pilot technology. So the dogfooding of the product internally was very affirming of the route we were on.”

Read more about how the co-founders of Pilot pulled off a successful three-peat startup.

Bryant Chou, co-founder of Webflow, shares a similar standout memory of watching his co-founders, Vlad and Sergie Magdalin, use an early version of the product to build a site in minutes.

“The very first time I realized that Webflow was going to be impactful was when Vlad and I pushed the latest version of our code so that the product would work end-to-end. We sat Sergie down to try it. And then I watched him as he dragged a div onto the canvas, then added a class to that div,” says Chou.

“Right in front of our eyes, Sergie was building the very first Webflow site. He created something in five minutes that used to take a proficient developer five hours — and that just blew us away.”

Read more about how Chou built Webflow with unrelenting customer empathy.

Founder morale is rising

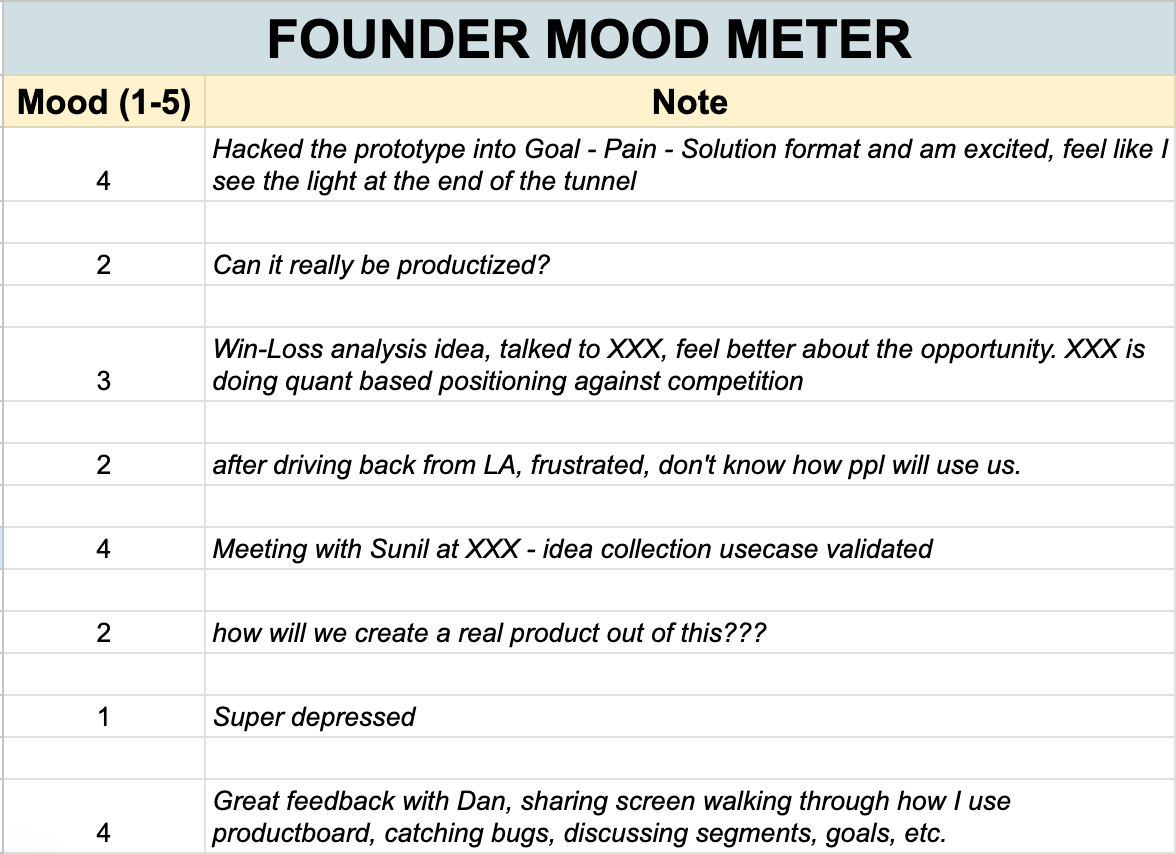

It may feel like a flimsy gauge of your startup’s success to simply ask, “How am I feeling?” But when you track your own emotions as a founder consistently, you can trace a regression line through all your day-to-day happenings and pull out a trend, just as Hubert Palan discovered.

The Productboard CEO and founder created a “founder mood meter” where he wrote down his mood three times each day, rated on a scale of one through five. Upon reviewing his entries, the takeaway was clear: When your mood is consistently high, things are working.

“I measured my own happiness as a proxy for the customer's happiness. At first, it was completely up and down. Eventually, I started feeling much better about where we were headed once the feedback became consistently more positive. It became obvious that there was a real market here — not just a few nerdy tinkerers,” Palan says.

Read how Palan harnessed lean startup principles to find product-market fit for the unicorn startup.