Today on The Review, we're excited to launch a brand-new series on product-market fit, spearheaded by First Round partner Todd Jackson (former VP of Product at Dropbox, Product Director at Twitter, co-founder of Cover, and PM at Google and Facebook). Jackson shares more about what inspired the series in the opening note below, but if you want to dive right into our first interview with Airtable co-founder Andrew Ofstad, click here.

Product-market fit is one of the most important, yet elusive, concepts in company building. It’s not a clear metric you can measure or a milestone you can easily check off your to-do list. I think of product-market fit as the transition moment you feel as a founder when you go from "pushing" your product on people to them "pulling" it out of your hands. But the path to get there is deeply personal. One founder’s journey to product-market fit may look totally different from another’s, and yet both paths could be completely valid — which can make it difficult to discern which lessons you can draw when you’re on the outside looking in.

There’s certainly been an uptick in articles on the subject in recent years, yet surprisingly little truly useful information out there on the concrete steps it takes to find product-market fit. The recommendations that do exist either tend to be too rigid because they’re based on one person’s experience, or too broad to be actionable.

Finding PMF has been a constant theme throughout my career, so I’ve experienced this journey firsthand — taking Gmail from beta to more than 200 million users as a PM and starting my own company, Cover, back in 2013. Now, as a Partner at First Round, I spend my days helping founders tackle this very challenge.

I’ve seen the quest for product-market fit take on more urgency lately, as follow-on funding becomes more difficult to secure and the pressure to hit stellar metrics has set in. So I’ve spent the better part of this year interviewing founders who’ve already cleared this hurdle to help inform the journey for earlier-stage founders. (Check out the post on validating startup ideas that I shared earlier this year in Lenny’s Newsletter or a few of the In Depth podcast episodes I’ve guest hosted on the topic.)

Today, I’m excited to share that I’m teaming up with the First Round Review team on a new series dedicated to telling more of these stories. We’ve already shared some fantastic resources here on The Review — like the widely-read PMF playbook from Superhuman’s Rahul Vohra — and I’m excited to contribute to growing our collection of advice on this topic.

Here’s what you can expect: Every other week, I’ll share an interview with a founder so you can hear about the most pivotal moments on their path to product-market fit — from how they stumbled into their company idea to their first “aha moment” and all the nitty-gritty details in between.

I’ll be talking to dozens of founders across backgrounds, verticals, and stages to showcase the varied paths to PMF. While there’s no singular playbook or recipe to follow, I’m a firm believer that there’s a lot to learn from reverse-engineering the frameworks and tactics others relied on to hit it big. My hunch is that, if we collect enough stories, we can start to pull out themes, patterns and insights that can be used to better inform advice that actually helps founders get to PMF.

I hope you’ll follow along. Feel free to share any feedback with me over on Twitter, or suggest guest ideas for future interviews!

With that, let’s dive into my first interview, with Airtable’s Andrew Ofstad.

REWINDING THE CLOCK ON AIRTABLE'S STORY:

After a decade of company building, the Airtable team has some stats to show for it. The low-code platform boasts a customer base of over 300,000 organizations, including the likes of Amazon, Baker Hughes, Netflix and Nike. In fact, an astonishing 80% of the Fortune 100 use Airtable.

The low-code movement is firmly established, the company is focused on going global (opening its first international headquarters in London), and the team has raised $1.36 billion in funding, with an $11 billion valuation.

But like any polished story, if you rewind the clock back to the earliest days, the picture looks decidedly different. So many tiny details get glossed over with the passage of time and the halo of success, whether it’s the struggle of architecting the first prototype, or the challenges of figuring out the ideal customer profile. In Airtable’s case, building a big, horizontal product made that path all the more daunting. (Browse their templates section to get a flavor for the wide range of use-cases this flexible product can tackle, ranging from tracking bugs and marketing campaigns, to cattle ranching and finding baby formula.)

In 2012, Andrew Ofstad and his co-founders Howie Liu and Emmett Nicholas set out on what would be a “slow build.” In his current role, Ofstad spearheads the company’s long-term product bets, but today he takes us back to the beginning, tracing Airtable’s path to product-market fit.

We dig into the nitty-gritty of how they validated the initial vision and approached the early product-building journey from private alpha to launch. From the glimmers that it was starting to catch on, to the challenges of positioning and thinking about the competition, there are tons of lessons in here for aspiring founders — especially those building horizontal products.

EXPLORING IDEAS AND VALIDATING THE VISION:

The -1 to 0 phase of company building can take many shapes. Some founding teams coalesce around a particular idea rather quickly, while others spend several months exploring completely disparate industries. For the Airtable trio, the early vision was broad, but had a clear end goal.

“The early vision was to democratize software creation. We all felt we had this crazy superpower of being able to build software, which had given us these advantages in our careers. You can have tremendous influence in an organization — even if you’re not in leadership — by building software and deploying it to people. So broadly, we were exploring how to make software creation easier for non-programmers,” says Ofstad.

Much of that inspiration stemmed from computing history. “The early days of computing were using these arcane command lines to operate a computer. It was only through Xerox PARC’s GUI and Apple’s Mac that computing was made more accessible to everyone. We wanted to do the same thing for software — to give everybody a software stack they could build useful software on top of.”

But an idea in hand isn’t enough — assessing its promise is the next critical hurdle for aspiring founders to overcome. How do you prove to yourself (and others) that it has legs?

Taking your time here is key, Ofstad says. He advocates for what he calls a “long gestation period,” recommending that founders resist the temptation to dive into building features and shipping underbaked concepts quickly. Instead, he advises founders dive deep and hit the books to examine the problem from every angle: what’s come before you, where there’s whitespace to build in the market, and your own motivation to see it through:

- Don’t follow the fad: “We were a bit contrarian. At the time, it was all about the Lean Startup, getting early customer validation and failing fast. This book making the rounds called ‘The Four Steps to the Epiphany’ espoused this lean company development model, where you put out a super rough prototype to get to know the customer and quickly pivot,” he says. “We took more of a first principles approach — we didn't want to just throw spit at the wall, so we went really deep on the problem before formally breaking ground on building the product and trying to get customers.”

- Brush up on the prior art: “We were intellectually excited about going down that path of this general space of software creation. So we spent a lot of time doing research. It was almost like being on a sabbatical, reading all this prior art of old computing pioneers, like Douglas Engelbart and Bill Atkinson, and even contemporaries, like Bret Victor. We played with old products, like HyperCard, that had flavors of software creation for everybody, and read a lot about how to visualize complex systems.”

- Assess the potential and spot the openings: “We spent a lot of time thinking about ‘What is the market for this?’ Spreadsheets have been around forever, but most of the time, people use them to track objects: people, companies, simple tables. They're not doing modeling and number crunching, which they were invented for,” says Ofstad. “And when Howie was at Salesforce, he learned more about the enterprise software market and saw that most business applications out there are essentially just databases with views and business logic on top, and there's a lot of reinventing the wheel in vertical software. So we saw the business potential of how Salesforce — this giant platform — was more or less just a flexible database. But you had to be an advanced admin to understand how to configure and build it. We saw the potential of opening up that type of software creation to a much larger market.”

- Make sure you’re dedicated to digging in: “We took our time early on to make sure that it was something we were committed to. If you’re going to tackle a horizontal product that’s pretty hard to market and has a lot of stuff that needs to be built to get to MVP, I'd recommend taking that time to make sure that you're super interested in the problem space and like the people you're working with. It would've been hard for us to get to that level of conviction without having that period of going deep on the problem.”

We had this long, early gestation period where we did our research on the technological challenge, the market and precedent before us. We saw that we could build a big company, but knew that it might take a long time to do, so we had to get into the right mindset.

BUILDING THE EARLY PRODUCT: SLOW-GOING ON THE PATH FROM PROTOTYPE TO LAUNCH

“The first version was trying to prove that we can make a database easy to use. It was like a prototype — a lot of smoke and mirrors. We focused 100% on the UI and the interactions. We didn't really have a backend, it was just persisting to local storage and the browser — enough to make sure we could test the interactions and get to a point where people could play with it. We wanted to put it in front of people and ask them to try to organize something and see if they could actually do it,” says Ofstad.

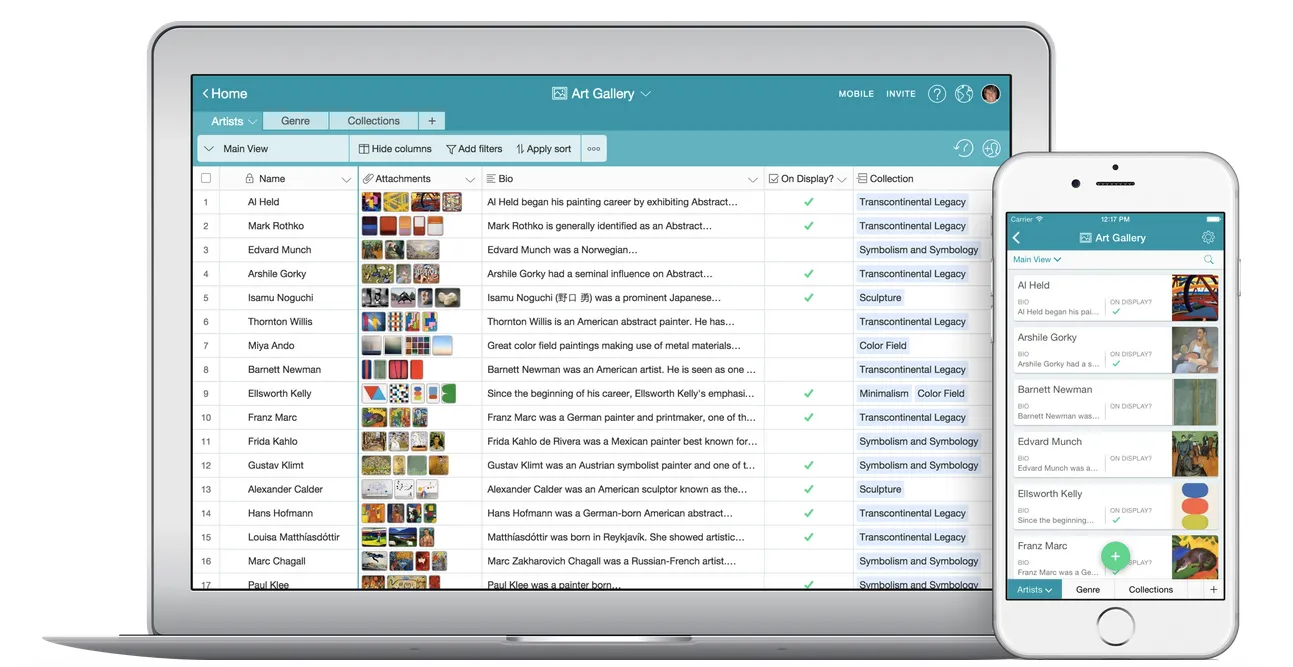

Product differentiation would be key to Airtable’s success, but that early version looked suspiciously like a spreadsheet. “It was a database underneath, obviously, but we co-opted the spreadsheet interface, which is familiar to most knowledge workers,” he says. “We built a lot of the same interactions, although we had typed fields, tables, and links between foreign key relationships. But for a lot of people, it just didn't click. It took us a lot of iterations and doing things like building templates to make it feel different.”

Here’s an example: “Even smaller details like fields that were colored select options helped convey that mental model that you're dealing with records, not a spreadsheet. We also always emphasized direct manipulation, making it feel like you could reach out and touch your data. When we first built attachments, it came with the drag-and-drop functionality because we wanted it to feel super interactive, so we put a lot of effort into real-time architecture.”

Despite these initial hurdles, there was still an early adopter crowd. “They were programmers or database people, more of that tinker persona who’s very structured in their thinking,” he says. “We had a friend who was a video producer and he started tracking his video productions, creating tables of his cast and crew and linking them together.”

Many founders might be tempted to cast a wider net and get more users onto the product — but Ofstad again cautions against moving too quickly here. With just pockets of those click-into-place customer moments, the Airtable team knew it would be an unusually slow path to launch.

As you assess your own timeline, Ofstad recommends stepping back and reassessing whether a public launch will truly help you achieve your mission-critical goal in this early phase. “We were focused on de-risking the main risk for the company as early as possible. For us early on, that was, ‘How do we actually make this database accessible to non-programmers?’” says Ofstad. “That meant it was all about making it easy to use, iterating on a prototype and getting lots of feedback. It seemed like launching the product publicly wouldn't really get us more data or accelerate the path to getting there.”

Separate the concept of trying to get feedback from customers and refining the product from the concept of a public launch.

Ofstad breaks down how that principle worked in practice:

Alpha: Stay lean while you de-risk your biggest hurdle.

“Our strategy was to build a very horizontal product and then roll it out to more people over time. Very early on, we had a private alpha. It was invite-only, but you could refer other people, so that helped us get some organic growth, but not a ton,” says Ofstad. “After maybe 100 people or so, eventually we felt like we were in a good place.” This took two years, he says. “We had to build so many features to get to something useful.”

In addition to delaying a public launch, this strategy also kept the team comparatively lean — avoiding the early-stage trap of overhiring. “This work in the alpha phase would have been really hard to parallelize. You can't hire a bunch of engineers to make that go faster. It actually would've been counterproductive to try to scale it up a lot more because we needed to nail that foundation of the database. Hiring a bunch of people would have made it harder to be nimble and change the direction of that foundation,” he says.

If you’re building a similar type of product, Ofstad’s advice is to keep the feedback loop extremely tight and loosen your expectations around what your MVP “should” look like. “We'd sit down with our customers to see what they were using the product for. With horizontal products, you build this very generic thing and the cool part is seeing how people use it,” says Ofstad.

The MVP for our product was not any one thing. With a horizontal product, you're constantly unlocking new use cases.

“As we added new features, we unlocked new use cases. It was a slow roll of adding a calendar view and then suddenly seeing people using it for marketing use cases. Or adding kanban and seeing people use it for processes and pipelines.”

Beta: Test, test, test — but push to go faster.

“Eventually we got to a spot where we felt comfortable putting it into beta and trying to get some more customers. We launched publicly on Hacker News in 2014. We kept it as beta to give us an opportunity to have a bigger public press launch later on, and to have that beta tag on in case things didn't work right,” says Ofstad.

“In hindsight, maybe we waited a bit too long. We probably could have launched earlier and cut some features. But for the most part, we got the learning we needed and launched when we were ready. We were trying to see if it was resonating with our customers and if we could handle the potential extra traffic. Did we have the features so people won't lose data and it won’t be a big headache for us to recover it?”

FIGURING OUT GO-TO-MARKET AND ASSESSING THE COMPETITION:

“Early on, the way we approached our go-to-market was opposite of what most companies do, which is start with a super niche audience, find them, target them and expand to new markets,” he says.

“We started completely horizontal with a blank-slate product, and we got more and more narrow with our focus on landing customers over time. We started seeing organic adoption for different use cases and then we’d create hundreds of templates.”

“But it's really only been the last few years that we've gotten super targeted with our go-to-market motion,” says Ofstad. “We've since gotten much more opinionated and narrowed the aperture. Now we're mostly focused on marketing and product organizations in terms of how we initially land in a company. Part of that has just been having a much more mature executive team to help us refine this, with our CRO Seth Shaw and our CMO Archana Agrawal” (who shared her marketing lessons in this previous episode of In Depth).

But that path to figuring that out wasn’t easy. Here’s Ofstad’s advice for fellow horizontal product builders:

1. Double down on early traction (carefully).

“When you’re building a horizontal product, as soon as possible, understand where people are getting value from your product and really double down. You can build a horizontal product with a deep customer understanding of a specific use case. It's just a matter of not going too deep on it,” he says.

“There's a balance because you also don’t want to take the first use case that pops up, especially if it's not going to be something that will grow a lot or fit your longer-term vision of the company,” says Ofstad.

“But as soon as you see some validation where the customer is in the wheelhouse of what your broader vision is for the product, co-build the product with them. Focus on understanding the problems and generalizing those into capabilities that might solve a bunch of different use cases.”

If you build a hyper-specific app for one function, it's not going to capitalize on the broader vision you had for the product. Get data points from customers, but also pattern match that against your broader vision for the broader horizontal platform you're trying to build.

2. Blend the functional and the aspirational.

One of the biggest hurdles with a horizontal product was messaging. “Over the years, we've gotten more and more focused on how we describe the problems we solve and the use cases we're good for. But before we had product-market fit, it was hard to describe the product in the early days,” says Ofstad.

“We had a couple of messages. One was, ‘This is a way for you to build software.’ We were mostly just a database still. We hadn't built things like automations, but that's how we framed the mission. And then separately, we'd say ‘It's a spreadsheet database hybrid, or a spreadsheet with the power of a database.’ That came from the way our customers would describe us, which was, ‘It’s an easy-to-use database,’ or ‘It's a spreadsheet, plus plus.’” (We’ll note that the “Show HN” copy from 2014 read: Airtable, a real-time spreadsheet-database hybrid.)

3. Map out your adoption.

Those “we just went viral” product-led growth stories are never all that relatable for most startups that are still struggling to find traction. Ofstad digs deeper into Airtable’s growth trajectory:

“It happened in a lot of different S-curves. We started seeing media companies where we spread word-of-mouth. Or the head of production would go from Netflix to some other company and they'd bring the tool with them. It was very slow, and wasn’t until 2018 or so that it started to really inflect,” he says.

“That functional and industry-driven word-of-mouth growth, combined with us building new capabilities that unlocked more use cases and having the organizational maturity to expand within companies, all layered together to cause pretty solid growth in the past five years.”

But much of it came down to the nature of the product itself. “Somebody builds something in their table and they share that with people on their team to do critical work. Once people start doing work in it, it generates useful data and other people want to consume that. So people invite them to the base. We describe those internally as golden datasets, those critical datasets for a company, like a product roadmap or a marketing calendar. Once you get to that point, you get a lot of viral adoption on top of that.”

Key to figuring this out was the ability to track these metrics. “The more important thing we did is that early on we had things instrumented so we'd get a notification every time somebody signed up,” he says. “Once we started getting more adoption at larger companies, we built out these network graphs that would show how the product spread from individual to individual, and then team to team. That helped us understand the mechanics of the product and gave us an intuitive mental model of viral adoption.”

4. Think about pricing as positioning early on.

“We thought about pricing from the earliest days. Even during our alpha with our first pockets of users, we had a pricing page with a few different plans. It mostly described features we hadn't built yet, but we at least wanted to frame that this is a product we're going to charge for,” says Ofstad.

“We also chose price points from a positioning standpoint — how do we position against the value we think we'll bring to companies? We priced more against the Salesforces and ServiceNows of the world, as opposed to the Evernotes and Dropboxes. We did anticipate that people would build applications that power important company processes on Airtable, so we wanted to price accordingly,” he says.

“The thing we didn't build for quite a while was the actual billing system to charge our customers. We actually had a place, buried in one of our settings pages, where customers could voluntarily put their credit card in, but we didn't charge them. We were amazed because some of our customers actually found this and put their credit cards in and then complained to us that they didn't get charged,” he says.

While this may seem like the ideal problem to have, Ofstad notes two factors that may be overlooked when founders hesitate over getting into pricing too early. “Our customers were worried that Airtable would disappear. So while we’re building pricing from a marketing standpoint, it was also important to convey that we were here to build a durable business,” he says.

“And I think I would be skeptical myself if I start using a product and it's not clear how they're making money. You wonder: Are they gonna sell my data? Are they going to totally price gouge later on? That transparency is actually good for the customer too, and helps build trust in the product.”

5. Keep your head pointed forward when it comes to the competition:

“We were fortunate to pick a space that didn't have a lot of competition breathing down our neck early on. Of course, we did have comparable products and substitutes that customers would use, like a spreadsheet or a project management app, but those were very different types of products,” he says. “To be honest, no-code wasn't really a thing back in 2012, and B2B productivity software wasn't super sexy — it was very much about consumer social. That afforded us a landscape where there wasn't a lot of direct competition.”

This, of course, is no longer the case. But the increase in competition doesn't faze Ofstad. Instead, here’s his philosophy: “I used to run cross country and track in high school, and my coach would always say, ‘Don't look behind you. You'll slow down. Just keep your head pointed forward and sense what competition is doing, but don't focus on it too much, because you'll lose track of where you're going,” he says.

“The best thing you can do is to have your own sense of the vision for where you want to go and to make sure you're going in that direction. But of course, you can learn a lot from other products in the ecosystem, see what cool products are launching and understand what people are using and how the consumer tastes are adjusting.”

Staying savvy on good products and trends in the broader ecosystem is super important. But that’s different than focusing on your direct competitors and getting into a myopic state of, ‘Oh, we’ve gotta build this because they did.’ That's counterproductive.

FINDING TRACTION: THE “AHA” CUSTOMER MOMENT

Product-market fit isn’t a singular moment in time — and it’s also a moving target. But looking back, there tends to be an “aha” moment for the founders, where it all clicks into place.

“There are a couple of different milestones that stand out. When you initially see one person getting value out of the product, like our friend using us for video production. Or when you first see a team using us and getting value out of it — we had a nonprofit that was like 10 or 15 people that started using us early on for managing all of their applicants,” he says.

But the moment that sticks with Ofstad was much more visceral. “We landed with WeWork and it grew virally within the company, going more or less wall-to-wall. When I was on this customer tour to New York — after having mostly interacted with customers over the support channel or Zoom — I visited WeWork. I looked around and everybody's computer monitor had Airtable open. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is actually a thing. People use it.’ It became so much more real at that point. That was the first moment when I thought we'd actually built something that might make it.”

Sitting here in 2022, it seems safe to say they did indeed make it. But for Ofstad, the journey is far from over.

“We're constantly trying to make the product easier to use. And that's both for the person that's building apps on top of Airtable, as well as the end-user who's using those apps. We’re obviously focusing on the enterprise more and more, on our customers who are running large departmental and company-wide processes on Airtable. So there's a lot we have to do around larger-scale, better permissions, all the things you'd expect,” he says.

“More and more, we're thinking of Airtable as a connected apps platform, and that's the category we're defining. What that means is we want to give individual teams and departments control over building and deploying their own software while at the same time, connecting to shared data sets and shared tables that help to break down silos within organizations.” (If you’d like to dive deeper into Airtable’s long-term strategy here, we recommend this Protocol profile on Ofstad’s co-founder Howie Liu.)