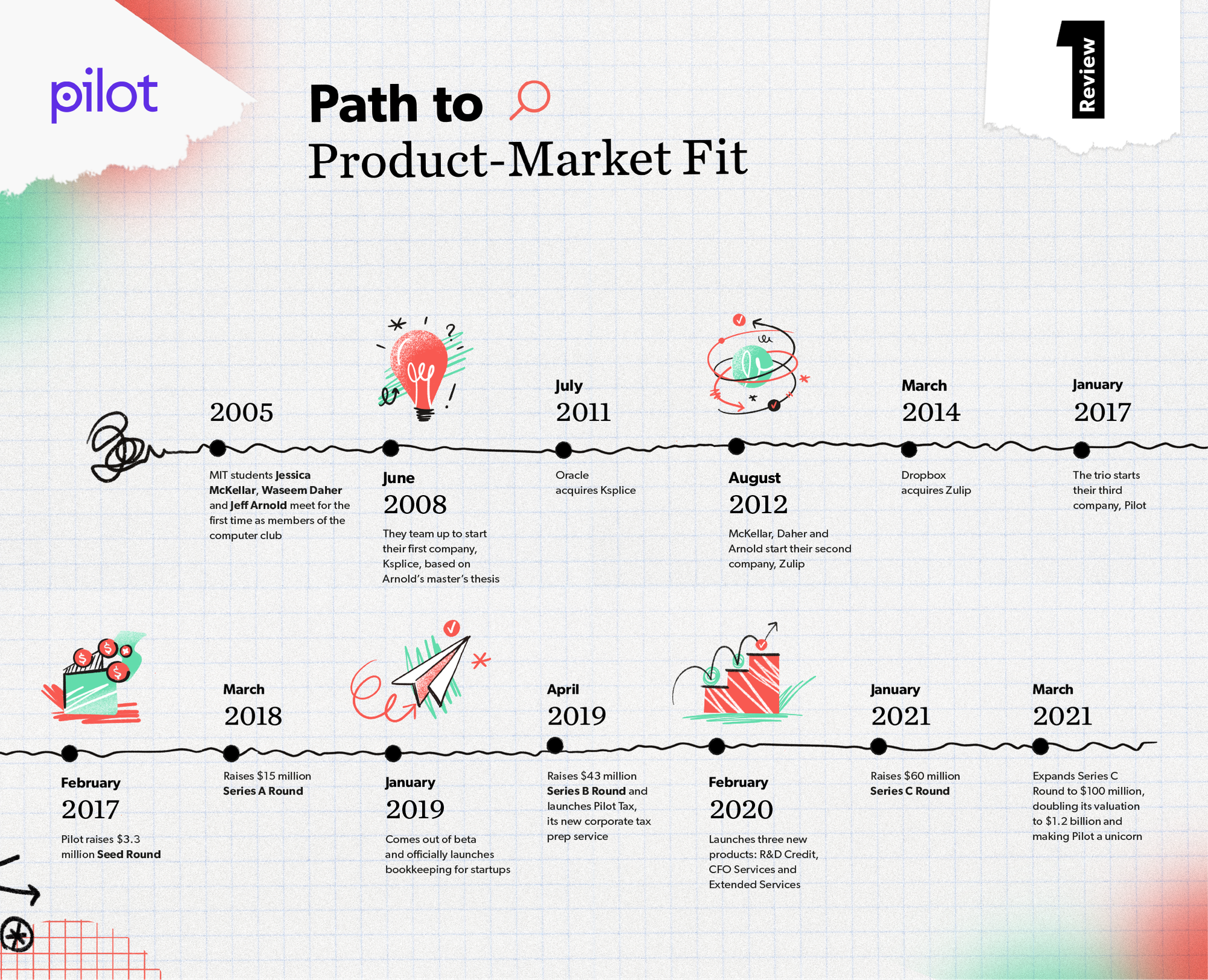

For a founding team to achieve startup success together just once in their lifetime is impressive. Twice is remarkable. Thrice? Practically unheard of. That’s part of what makes the story of Jessica McKellar, Waseem Daher and Jeff Arnold so unique. Not only did they build successful startups together three times over (with one acquired by Oracle and another by Dropbox), but they did it while maintaining a deep mutual respect that most founding teams can only dream of.

“Jeff, Waseem and I have complete trust in each other to do what is right for the business,” says McKellar. “It’s a rare thing to experience. I would never let go of it.”

Before they were at the helm of Pilot — a $1.2-billion company providing bookkeeping and tax services to the likes of OpenAI, Lattice and Airtable—they were just three self-professed computer nerds at MIT. “The nerdiest of the computer nerds hung out at the computer club,” jokes McKellar. “And that's where we met.”

Soon after, in June 2008, they started their first business together, Ksplice, which built technology that made it possible to update Linux kernels without rebooting and causing downtime. The trio lived in a rundown row house in Cambridge, bootstrapped the entire operation, grew it to seven figures in revenue and sold it to Oracle in July 2011.

After working at Oracle for a year, the founders were once again itching to start a new venture together. Their next company was Zulip, a pre-Slack group chat app that was acquired by Dropbox in March 2014.

With two successful exits beneath their belts (all before the age of 30), it would be understandable if the trio decided to hang up their founder hats — at least for a while. But after a couple of years at Dropbox, McKellar, Daher and Arnold decided to start yet another company. This time, bigger. This time, one that could go public.

“We wanted one last go-around. We wanted to have the experience of building a company to a later stage than Ksplice and Zulip had reached — a company that is wildly successful and financially transformative,” she says.

But first, they needed to find the idea that would get them there. In this exclusive interview, McKellar (Pilot’s co-founder and CTO) shares the behind-the-scenes story.

EXPLORING AND VALIDATING IDEAS

When the three founders began brainstorming their next business in late 2016, they were sure of three things:

- They wanted to solve a business problem, not a consumer one.

- Their target audience, at least initially, would be startups and small businesses.

- They would only pursue an idea that all three of them were jazzed about — the founding trio sticking together was a non-negotiable.

From this jumping-off point, they created a list of problem-solutions they thought had potential, mining their past experiences for clues. And, as it turns out, a kernel of the idea for Pilot could be found as far back as 2009 when they were recent college grads bootstrapping Ksplice.

“We certainly couldn't afford a back office team back then, so we got a copy of ‘QuickBooks for Dummies’ and QuickBooks Desktop software and we tried to do it ourselves. We even wrote some software to try to auto-close the books ourselves. So that experience of having to figure out how to take care of our own finances was a problem we had experienced ourselves nearly a decade prior,” says McKellar

To validate that this problem resonated with a much wider founder audience, they went to startups and small businesses and asked: What are your biggest pain points? Then, they expanded their scope and talked to teams in finance, accounting, legal and HR across a variety of business sizes, from SMBs to mid-market companies.

The overwhelming, loudest theme that came out of customer discovery was that getting your finance and accounting taken care of was as unsolved a problem in 2017 as it had been back in 2009 when we were at our first startup and trying to do it ourselves.

“That seemed like a thread that was worth pulling on. So we started pulling on it,” says McKellar.

The idea for a bookkeeping solution won for four reasons — all strong indicators that there was a clear path to product-market fit if they continued down this road:

- It was the most prevalent and pressing pain point that came up in customer discovery.

- It was in an enormous market.

- The average sales price (ASP) was high.

- The competition in the space was low.

And so, after some brainstorming and customer discovery, the founders landed on the idea for Pilot, a monthly subscription bookkeeping service for startups. Did they entertain other ideas? Yes, they toyed with building mid-market HR software. Could they have taken the HR software idea and made it a success? Sure.

“But at some point, you just have to call it. You have to stop talking about ideas and just say, ‘Okay, we're going to try it.’ And what does it mean to try it? It means you try to get someone to pay you. Payment is the true proof,” she says.

GETTING THE FIRST PAYING CUSTOMERS

It was now January 2017. Pilot had no engineers, no software, no bookkeepers. But that didn’t matter. The founders approached their fellow founder friends, verified that bookkeeping was a painpoint for them, and then asked, “Would you pay us $100 to take care of your bookkeeping?”

If the answer was no, they dug deeper to get to the root of their target customers’ hesitation.

But if the answer was yes? “We’d say, ‘Great, please provide your ACH details, and we will become your bookkeeper,’” McKellar recalls.

Believe it or not, no one asked to see their accounting credentials. “It's not like there was some clear, best-in-class provider that all of their other startup founder friends were using. It was totally fragmented. No one wants to go on Yelp and try to find the best bookkeeper for their startup. It's a trust-based decision. And what we had with our friends was trust. We were successful founders, so getting our friends to trust us with their books was no worse than choosing a random bookkeeper.”

With a few yeses in hand, Arnold and Daher started doing their first customers' books manually while McKellar looked over their shoulders and wrote code.

“Doing the books looks like this: You're importing transactions into QuickBooks, reconciling, categorizing. You're dealing with bills and invoices. There's a review process. You have to validate to yourself and to the customer that the books are correct. So we got really familiar with the QuickBooks APIs to figure out what's possible and what systems we would need to build,” she says.

Step one of building Pilot’s software was creating a checklist. "To build these big systems, you need to start getting the shape of the process flow. What are the checklist steps? What are the systems that need to be built? And then you just crank on it."

If you can articulate what needs to happen in a checklist, you can, piece by piece, translate that checklist into software.

As they cranked out code, they juggled dozens of initial customers, tracking them all on a whiteboard. Shortly after, they put up a website that accepted payments. At the time, they were charging $100/month, but as they took on larger customers, they bumped up their pricing to reflect the increased complexity and get the margins they wanted.

“Margin is an important part of how we assess the health and growth of the business because Pilot is not pure SaaS,” says McKellar. A quick point of clarification here — in addition to Pilot’s software, the company employs accountants, fractional CFOs and tax specialists who work with customers in tandem with the technology (more on that decision later). “We're delivering a service on a monthly basis. So we're very tender to margins,” she says.

At the beginning of any business, pricing can be tricky, and many founders just throw out a number to start charging something, anything. But as you get to know your market, you can get it down to a science, as McKellar explains: “We actually have a pretty tidy heuristic for pricing, which is, if you look out in the market, we know that most businesses, whether or not they're using Pilot, spend between a half a percent to one percent of their total spend on finance and accounting. And if you know that, you can build a pricing and packaging model around that.”

LAUNCHING AND FINDING PRODUCT-MARKET FIT

There’s often a lot of buzz around launch day for startups — with plenty of fanfare and, if you play your cards right, flashy headlines. But McKellar places so little importance on it as a strategy that she can’t even remember when Pilot officially launched.“What are launches really for anyway?” she says. “They're mostly about organizing yourself internally; rallying the team around a new feature, product, sales motion or marketing collateral; getting the team excited; and getting it out the door. For the most part, launches don't cause you to generate a bunch of new money. You might see a bump in website traffic or a spike in signups, but only briefly.”

For Pilot, we focus on delivering a service people love. They love it so much that they stay with us, and they tell their friends, who then become Pilot customers. That’s our go-to-market flywheel, and that's how our revenue grows.

But, if you had to pick the date when Pilot officially launched, it was probably January 2019. That’s when it came out of beta and became available to the general public. At this point, the company was already managing the books of more than 150 companies.

Having paying customers is certainly one sign of product-market fit, but what signaled to Pilot’s founders that they were on the right path? A memorable moment was when they started to see proof that their software was doing exactly what they’d built to do.

“Of course, we were using the software that we were building to close Pilot's own books. And there would be moments when the software would catch something that we had missed, like a double payment,” McKellar recalls. “And we’d realize that this wouldn't have happened unless we were using Pilot technology. So the dogfooding of the product internally was very affirming of the route we were on.”

The biggest turning point was when, without even trying, they started getting pulled upmarket and across verticals by their customers—an enviable position for any founder.

Customers kept coming back to us saying, “Can you do more for me? Can you also do my taxes?” That pull suggested that we were actually providing a customer experience that was so valuable that people wanted to not just pay us for bookkeeping but actually to expand the engagement with us.

EXPANDING THE PRODUCT SUITE

Finding initial product-market fit gave the founders the conviction they needed to start adding on new services and pursuing expanded customer segments.

“Given the goal of the company, which is to be the financial back office for a broad range of businesses, we had to break out of startups eventually,” McKellar says. “Startups are a very small percentage of the economy. Plus, we have the goal of building a company that's going to be independent for a long time and eventually go public, so we need to be on a particular revenue growth curve. We need to get to billions of dollars a year in revenue.”

It goes back to the initial spark for this co-founder trio to start their third company in the first place — with their sights set on building something much bigger than their first couple of ventures. But while Pilot’s founders have aggressive growth goals, they always balance those against their steadfast dedication to customer satisfaction.

“We're very protective of that go-to-market flywheel that's about the brand and the reputation we have that we can only earn by actually doing a good job. We need to be delighting our customers consistently. So how do we expand safely? Do we have the right instrumentation, the right feedback loops, the right expertise on the team? Honestly, the revenue curve is brutal if your goal is to be on the best-in-class path towards being a public company. Every six months, you're like, ‘Oh shit, what's our next additional revenue stream?’”

First things first: Don't ever jeopardize CSAT. You should never be so desperate to hit your numbers that you sacrifice customer satisfaction. We’re always asking, “What do our customers want us to do?”

Pilot’s founders knew the timing was right for adding a new product because this expansion was led by their customers, who were practically begging for tax services. To determine which customer segments they should go after next, again, the founders let the customer tide pull them in the right direction, looking at who was knocking on their doors and getting turned away. Ecommerce, CG&R and professional services firms were already showing interest in working with Pilot, even before Pilot sought them out.

“That meant that what we were already saying out in the market was resonating with them without us even trying to speak directly to these segments,” says McKellar. “So we decided to learn operationally about these types of larger businesses and figure out the delta from startups so we could adapt to it on the product side and on the service delivery side. Once we felt really confident that we could deliver a high-quality experience, we opened the floodgates from a marketing and sales perspective.”

In April 2019, Pilot raised $40 million in Series B funding and launched its corporate tax preparation service. And less than a year after that, three additional products debuted: R&D Credit, CFO Services and Extended Services.

THREE BIG LESSONS FROM THREE-TIME FOUNDERS

Pilot’s seamless additions to its core product point back to the enormous importance of choosing the right problem to solve. Well into their third business together, McKellar, Daher and Arnold have made the moves of seasoned multi-time founders. So if you’re not one yet, here are three lessons you can learn from these serial entrepreneurs.

PMF Lesson 1: Picking a big market Is first priority

“If you plan to build an enduring company, one that can be independent for a long time, one that can go public, the number one thing you need is a market that's large enough,” McKellar says. “A lot of other things you can change after you've started, but you can't change the size of the market. We’ve tackled smaller markets before. The market for businesses who care about rebootless kernel updates on Linux is a great market, but it’s not huge, which is why Ksplice was always going to end up being acquired. It's just too niche a product to live on its own independently. When we started Pilot, we knew we wanted to tackle a really big market, something that could have legs indefinitely.”

The sneaky genius behind the problem Pilot solves is that it’s an activity that’s legally required for all businesses, guaranteeing demand and longevity. Businesses all have to do their taxes, and to do that, they need bookkeeping.

We chose a problem that literally every business has. Bookkeeping is not a nice-to-have, it’s a must-have. And because of that, it's an enormous market, and our business is resilient even amidst economic turbulence.

PMF Lesson 2: Ensure the problem you solve is the problem your customers actually want you to solve

As three MIT-trained computer scientists, Pilot’s founders easily could’ve built a pure software solution, but by doing so, they would’ve missed the mark of what their customers were actually telling them. By listening closely to what their customers really wanted, the founders decided Pilot would be a combination of people and software.

“From talking with business owners and founders, nobody was saying, ‘Hey, I want more accounting software.’ People were saying, ‘I want to give this problem to someone else and have peace of mind that it’s being solved.’ The feedback was that they wanted someone else to own the problem from end-to-end.”

It’s a hard-won lesson from their Zulip days (their second company together) when the founders built the product they wanted as engineers, not the one that a wide swath of customers wanted.

“There were some companies that passionately used Zulip, like 8-10 hours a day average for the company, per person, and deeply integrating it into their workflows. But for everyone else, it was too hard and complicated. What we built couldn’t generalize to the broader customer base we were trying to target,” she says.

You have to be really careful about overfitting to your own experience. You need to make sure that you're selling something that is going to resonate with the intended audience.

PMF Lesson 3: Build a product that has natural extensions

“One thing that’s really attractive about bookkeeping as an entry point to the back office is that there are a bunch of natural extensions out of bookkeeping: taxes, fractional CFOs, R&D tax credits. It’s ideal to get that all done under one roof so you don't have to deal with and coordinate among multiple vendors. If we're your bookkeeper and your tax preparer, when the tax preparer has a question, they can just go ask the bookkeeper. We have a deep understanding of how Pilot does bookkeeping to make that exchange really efficient and avoid mistakes. There's synergy in the product. It's a better customer experience.”

This natural extension is what enabled Pilot to start with bookkeeping, and then have their customers literally pulling them into other product lines — rather than building second and third products and hoping they’d catch on with the initial customers.

HOW TO FORGE A CO-FOUNDER RELATIONSHIP THAT CAN GO THE DISTANCE

It’s been said that VCs invest in teams, not ideas — and Pilot’s co-founders are a classic example of why. When it’s time to choose who to start a business with, it pays to choose wisely. Notably, back when McKellar, Daher and Arnold were running Zulip, angel investor and Kayak.com co-founder Paul English didn’t like their idea for a group chat app—but he chose to invest anyway because of the team.

"Their dynamic was so powerful that I would almost invest in whatever they do," English told CNN back in 2014. (And yes, English is now an investor in Pilot, too.)

So what makes McKellar, Daher and Arnold such a dream team? Let’s dissect the dynamics of this trio.

1. Separate areas of ownership

Early on, the three founders established separate, non-overlapping areas of expertise. This allows them to be subject matter experts in crucial areas of the business and trust each other to take care of their distinct areas of ownership. This may seem a bit surprising — after all, the trio met as admitted computer nerds at MIT. But there were some nuances that each brought to the partnership beyond a sharp acumen for code.

“As a people person, Waseem gravitated toward the sales and go-to-market side and was the first salesperson at Ksplice,” explains McKellar. “Jeff is the kind of person who reads corporate tax law for fun. He brings that analytical mind and conservativeness to the business to make sure that we're running it safely. And then I’ve always stuck with the product side, staying closer to the customers.”

2. Alignment of values and motivations

When they started brainstorming ideas for what would later become Pilot, they were already in agreement on wanting to solve a business problem for startups and eventually grow the company to go public. They were only diving back into the world of building from 0-1 with their sights set on a massive outcome.

“We're values aligned about what kind of company and company culture we want to build. And that’s been key to functioning well as a founding team.”

3. The ability to handle conflict well

“Like any relationship, there are ups and downs,” says McKellar. “It probably took Jeff and me a solid seven years to really get along. But why did we start working together? Because we thought we were the most effective potential cofounders that we knew. And why did we stay together? Because we proved that we were so effective as a group. If you have that alignment, if you have that trust, that's so precious. We would never let go of that.”

So even if you and your co-founders are squabbling, ask yourselves this: As business owners, are you able to deliver results together? If you’re consistently delivering the business outcomes you want, you’re proving your effectiveness as a team and are likely able to channel those conflicts into growth.

THE PATH AHEAD

A lot has changed since McKellar, Daher and Arnold bootstrapped their first startup from a mouse-infested house in Cambridge. Today, their third venture, Pilot, is a Series C unicorn with over $150 million in funding and noticeably cushier digs: one office in San Francisco with a view of the Ferry Building and another in Nashville with river views.

But three startups later, two things have remained the same: the founders’ closeness to their customers and to each other. McKellar still occasionally does bookkeeping herself and hops on customer and sales calls every week. "Nobody should be closer to the customer experience than founders,” she says.

When asked who her most memorable mentors have been during her 15-year career, she says, “My co-founders, Jeff and Waseem. They’ve had a tremendous impact on me, not just as a founder and a business owner, but as a human being. I'm deeply grateful to have been in the crucible of this startup experience for so long with these two people who I have such deep trust and respect for.”

If their venture history is any indication, these founders are not ones to rest on their laurels. They’re forging ahead toward the vision they’ve had for Pilot since its inception in 2017.

“We’re on the path towards building a profitable company,” says McKellar. “That means staying on that revenue curve and continuing to climb upward slowly on those margins. From there, you grind it out. It's kind of a math problem. You know what ARR you roughly need to have by the time you should be going public. You know what your metrics and margins should look like. So the next five years for Pilot will involve continuing to build out that rigor internally, busting our asses to stay on that revenue curve and, first and foremost, delighting customers.”