The scene is often romanticized in magazine profiles of successful founders: the keen observation jotted down in a notebook. The serendipitous conversation that clicks the puzzle pieces into place. The idea is where everything begins — at least, that’s what we’re led to believe.

All you have to do, these stories seem to imply to aspiring entrepreneurs, is wait to be struck by the muse of inspiration, which isn’t the most actionable strategy. But that’s exactly the problem with the mythologized startup epiphany. In the retelling of the spark that ignited the brilliant success story, the more messy parts of the journey from -1 to 0 often get lopped off. What can appear like some divine revelation is actually the product of months or years of interviews with experts, endless pivots, and tons of “That’ll never work” conversations.

When we start with the story of the brilliant idea, we’re glossing over all the hard work that went into unearthing it.

From outlining the unique insight, to capturing how customers might respond and sizing the market you’re going after, there’s a long punch list of things to chase down. In other words, if you want to find the next great startup idea, you can’t wait for the proverbial lightbulb moment — you have to do your homework.

As we’ve said, before a founder starts building their castle, they have to make sure they’ve picked the right piece of land. To help aspiring builders survey potential plots, we’ve gone back through our archives to surface the best advice from first-time entrepreneurs and repeat-founders. The 12 tactics they share here offer more concrete tips for reverse-engineering these fabled eureka moments, whether you’re in the wide-open ideation phase, or contemplating a hyper-specific direction.

This collection of advice contains frameworks for brainstorming, questions to help pressure test concepts, and even thoughts on how to best explore a new idea with a potential co-founder. Whether you choose to adopt just one, or a combination of them all, we hope they’ll help you accelerate on your course to finding the right problem to solve and diving into the work of starting up.

START WITH THE RIGHT MINDSET:

1. Put more effort into problem selection than you think you need to.

When it comes to the problem-selection phase of finding startup ideas, Ayo Omojola has plenty of experiences to tap into. He’s currently the VP of Product at Carbon Health, was the founding PM on the banking team for Cash App at Square, previously founded a YC-backed startup and actively angel invests — all of which adds up to a unique lens for finding and evaluating startup ideas.

“When it comes to a new idea, it’s so much more important to be certain, or as sure as possible, that the questions you’re answering are worth asking to begin with,” he says. “When I think back to my last company, I was co-founders with my brother and a friend. We picked a problem to tackle that we found really technically interesting. We cranked for years and worked so hard and it just didn’t matter,” he says.

“The lesson I took from it was that we had put so much effort into the actual work, and had not put nearly enough effort into choosing what to work on. That was a much bigger determinant to our outcome — we hadn’t chosen a large enough market. If you pick a big domain that’s rich with opportunity, it of course matters how hard you work, but you also get so much more leverage.”

Omojola pinpoints how this grind-it-out mindset might be a product of our school days. “What we’re taught when we grow up is that our outcome is 100% correlated to our effort. If I study hard for a test or work hard on a project, I’m going to get a better grade than if I don’t try. So I’ve always just assumed that when things aren’t going well, I just need to work harder,” he says.

Choosing a problem that matters, even if your work is average, will generally yield a better outcome than choosing a terrible problem, even if your work is excellent.

2. Prepare your pack — and get ready to have your ideas challenged.

“Doing a startup isn’t a sound financial decision. Logically, the odds are so stacked against you that it doesn't make any sense. Jumping into life as a founder is a romantic decision. It's the kind of move you make when you want some adventure,” says Punit Soni. “But that doesn’t mean you have to leap off a cliff. Starting a company is like climbing a steep mountain — you need to take the time to prepare your pack.”

Part of the preparation includes keeping your mindset in check before you even set off. “You have to put a lot of intellectual vigor into figuring out exactly what you want to do. You need to carve out time specifically for that task by reading up, doing diligence, exploring different spaces,” says Soni. “It’s just like getting into a top school or amazing company. If you want the chance to start your own company, work for it — don’t wait to get inspired.”

Soni eventually landed on the idea that became Suki (a voice-based digital assistant for doctors) — but here’s a vignette of the work that went into unearthing it. Soni wanted to start a healthcare company, but he didn’t have much direction beyond that. “I had zero experience in healthcare, so I spent six months just shadowing doctors and embedding myself in large health systems to learn what kind of issues they were facing,” he says. “Nothing replaces in-person observation as a tool for figuring out both go-to-market and product.”

At one point, he thought he might have a winner. “It was essentially what Slack did for healthcare. There’s so much communication in a hospital, it seemed like there was a desperate need for it. And I knew I could build a great consumer product,” Soni says.

Over lunch in the break room with a group of nurses, he pitched his big idea. "They looked at me and said, 'Punit, I use a fax machine, pagers, Microsoft Outlook, electronic medical records, and paper documents on top of that. I will not use another communication protocol. In fact, if I see anybody else using it, I’ll actively try to stop them,” Soni says.

The criticism stung, but it was revealing. “It was an idea that I was personally very excited about. But it's an example of how you need to understand what the user is going through when you’re coming up with these Silicon Valley ideas to solve their problems,” says Soni.

“You have to spend the time asking a lot of questions and truly listening, but also translating. Most users don't necessarily know what they want, but they do know what's hurting them. It's your job as an entrepreneur to convert what's hurting them into a product.”

If you’re open to having your ideas challenged, you'll have a far greater chance of creating the product that your users actually want — not the one you think they want.

BLUE-SKY BRAINSTORM:

3. Set your compass with these three questions.

When you’re starting out with a completely blank slate, it can seem like you’re at an intersection with infinite pathways. Sasha Orloff knows the feeling. After founding and scaling LendUp for seven years, he decided to step down as CEO — without anything solid lined up. In the hiatus that followed, he took 100 coffee chats with founders, CEOs and investors to gather advice for his next move. Of course, one option was obvious — finding another entrepreneurial itch to scratch as a repeat founder.

“When you’re a founder, you’ve proven that you’re capable of creating something, and that’s really exciting. Becoming a serial entrepreneur is a way to keep creating,” says Orloff. “But fear of the ‘sophomore slump’ was acute among founders who left and started another company. And I admit that, no matter how many times people told me not to pay attention to those irrational fears and insecurities, I felt it too. For my next venture, I obviously wanted to create something that’s bigger and has a larger impact than my first — and that’s intimidating to say out loud.”

Whether you’re a first-timer or on your second or third bite at the apple, Orloff suggests finding direction as you search for a stroke of inspiration by asking yourself a simple series of questions:

- Where are the big problem areas in the world?

- What personal skills, advantages or insights do you have to be able to help solve it?

- How can you turn this into a viable business idea?

Orloff gives an example of how he thought through this framework: “During my time off, I was exploring how I could apply my background in entrepreneurship, technology, and experience with working-class Americans to democratize access and improve their lives,” he says. “If you’ve been thinking about a business idea for a long time, and repeatedly, it’s a good sign that you are passionate about it and should at least explore moving forward with it in some capacity.”

4. Hunt for ideas in nonobvious markets.

The trick to spotting a nonobvious idea lies in finding what bucks conventional wisdom before anyone else and scaling that unlikely idea into a high-growth company — something investor, operator, and High Growth Handbook author Elad Gil is very familiar with. To help potential founders find and mine nonobvious markets, Gil buckets the best types to go after: new technology, looks crowded but isn’t, and seemingly niche.

New tech:

“From mobile to social to crypto, there’s so many examples where people failed to imagine what a couple years of compounding developments would look like, in terms of technology speed improving, costs dropping or adoption increasing,” he says.

“We should be monitoring what’s compounding at a fast rate, or alternatively, where adoption is growing reasonably rapidly. The proof is in the growth rate or the extrapolated technology curve rather than the number sitting in front of you in that moment. You can also look at the technology and ask ‘Well, how much faster or better is this thing getting per year?’ and then look downstream. Or go the opposite way and ask ‘What happens if instead of a million people doing this thing, you had 50 million? What fundamentally changes in the market?’”

Looks crowded but isn’t:

“A busy market isn’t a negative signal in and of itself. If you do some poking around, you may find that it’s actually quite empty, whether that’s because no one has a great product or there’s lots of players with little differentiation,” he says.

You can still win even if someone else gets there first. Dig deeper to find differentiation and capture what they’re leaving on the table.

Given that many of the most interesting markets always look crowded, Gil offers a series of questions to hunt for signals of open space:

- Size up the competition. Are the competitors any good? Is it a great team than can crank out fast follows? How strong is their brand? “Many good ideas have bad implementations, so if you can come in strong and do it well you can win,” says Gil.

- Look for structural disadvantages. Are there unfair distribution mechanisms or other barriers? “Some crowded markets are indeed crowded or not worth it. Selling niche software tools to big pharma is an example, because there is just a small number of customers. Edtech is another area where I think it’s tough to gain traction,” says Gil. “Same with IoT. Large enterprises have a significant advantage because they can integrate and distribute, as opposed to a startup that makes a single ‘smart’ device, which doesn’t scale.”

- Suss out if there’s room. Is it a winner-take-all or winner-take-most market? Or is it more of an oligopoly structure? “You need to measure how much room there is. People often think it’s ‘game over,’ which if you look at things like payments, isn’t always the case,” he says.

- Calculate potential customers. Are customers actually being served well? What's the total penetration versus what it should be? How many people are actually utilizing the product and what is the true potential? “These questions can uncover that the incumbent product isn’t great,” says Gil. “Part of the reason Dropbox spread is because there was a real need there. If you think about it, the total population that should be using cloud storage solutions is close to all of the people who are online and using files. If you did the math before Dropbox came on the scene and looked at how many people were actually using a certain provider versus how many people should have been using cloud storage, you would have seen that the numbers were way off. It can be a quick back of the napkin calculation,” he says.

Seems niche:

When determining how big a market can get, founders and investors often delude themselves — in both directions. “Sometimes it’s not niche, it’s just boring. If you conflate the two, you’ll miss out on incredible opportunities,” he says. For Gil, there are four types here that warrant a second look:

- Too small: “I’ve heard so many investors say ‘Yeah, there's real uses there, but it's too small to go anywhere,’” says Gil. “But ‘small’ can easily turn into a mainstream product. I remember when Uber first got funded, a lot of the conversations were ‘They’ll only get 20% of the taxi market which is tiny.’ And in hindsight, Uber was actually solving a pretty dramatic user experience problem around transportation.”

- Too boring: “There are some real opportunities in areas where investors or founders essentially don’t want to think about it or they just don’t understand it. Some things like payroll aren’t very exciting,” says Gil. “PagerDuty is also one of my favorite examples. A signal for founders might be if you or your friends keep building the same internal tools over and over again. If it’s boring, just go do it, because that can become an advantage.”

- Too high-end: “You also hear that certain ideas are super high-end and can’t possibly scale. But you have to see the bigger picture and think about where it could go,” says Gil. “How else could it be applied or who else could be served if costs came down with scale? Think of Tesla when it was just the Roadster or how Uber’s initial pitch deck was focused on black cars.”

- Too personally unfamiliar: “As a founder, you should go with what you know, even though others may not get it — it'll be less crowded. For example, Katrina Lake turned Stitch Fix into a multi-billion dollar company. Emily Weiss founding Glossier is another awesome example. Male entrepreneurs may not have thought of these markets and investors might have overlooked their potential, but Katrina and Emily knew there was white space,” says Gil. “Drawing on your own experiences or getting diverse perspectives is a key tool for figuring out if an opportunity is really niche or if it just appears that way and is a massive market instead.”

5. Relax your constraints on the current reality.

As a professor, former CEO, longtime investor, and co-founder of First Round Capital, Howard Morgan has seen one habit differentiate good founders from great founders: the ability to relax constraints.

If you can’t think out of the box, make the box bigger. Start by relaxing constraints.

Morgan has seen both seasoned and green founders constrain their big idea from the get-go. But at ideation, it’s important to not limit yourself to the current reality — don’t be shy to engage in truly futuristic thinking.

Start with the technical. To build something that will change how people live their lives, you need to think beyond what’s available today. “When we were building internet companies at Idealab in '96 through 2000, the bandwidth that was available to most people was 56k dial-up. But to build interesting user interfaces, you had to assume broadband,” says Morgan. “Likewise, mobile bandwidth on 2G was not enough to do interesting data. So successful developers imagined away that constraint. “They said, ‘What if that goes away? We can build GPS. We can build rich applications that need hundreds of megabits per second.’"

When it comes to developing solutions to previously unsolvable problems, founders will also come up against the limitation of what is currently known, or knowable. But when relaxing knowledge constraints, it’s still important to observe the laws of physics. “We’re not likely to change those, so antigravity or perpetual motion machines should not be part of your plan,” says Morgan. “You should also understand that what may be known in 50 years is not that relevant to today’s startup. Thinking three to 10 years out is about as far as one should go for almost any founder building a company.”

As you consider startup ideas, here are several questions that might help you cast off these constraints:

- What technology is missing that is stopping you from achieving your end goal?

- What can you do now that lets you fold your more ambitious aims in later?

- What’s the science fiction version of your product?

- Have you pondered any particularly intriguing “What ifs?”

- When hiring teams to build groundbreaking technology, ask: What's the closest analog to what I want to do? Where can I find those people to relax that constraint?

SHARPEN YOUR VISION:

6. Take two weeks to tackle a hands-on project.

After leaving Stripe to start what eventually became Siteline, Gloria Lin was laser focused on finding the right fit — both in terms of a co-founder and the idea they would be tackling together. “People get hung up on having either a solid company idea or a specific co-founder in place from the start, but I don’t think you need either right away,” she says. “See the white space as an opportunity to try working together and a chance to explore interesting ideas at the same time.”

We recommend taking her advice here. Her playbook for finding a co-founder is one of the most detailed and intentional processes we’ve ever seen — and the set of 50 questions she used to probe compatibility is an essential tool for founding duos. (We focus on Step 3 of her process here, but be sure to read her full approach.)

When it comes to starting a company, you can figure out the right space to go after and find the right person to tackle it with in parallel. Don’t compromise on either.

After spot checking for initial alignment with a potential co-founder, Lin dives straight into tackling a project together. “Dive into exploring specific ideas with brainstorming and lightweight prototyping. The goal is to both make progress toward an idea and gain collaboration experience to see what it would be like to work together,” says Lin. “The first or second coffee chat may not tell you that much. But once you start doing some kind of project, you get so much more data on the person and their work style,” she says.

“For me, this was the fun part. It’s about getting your hands dirty, digging into a space, figuring out the need, and seeing if a startup idea has potential,” says Lin. “It’s also an opportunity to uncover if you’re actually interested in a certain area. A few times I thought I was passionate about a certain industry, only to discover through hands-on projects that I actually didn’t enjoy it.”

It’s not about tinkering aimlessly, though. Lin suggests timeboxing this exploratory period to about two weeks to maximize both learning fast and moving quickly. As for how to approach this period of exploration, her advice for consumer and enterprise startup ideas differs. When investigating a consumer play with a potential co-founder, Lin is a firm believer that you have to try to build something. “It doesn't mean that you have to build a full production-ready app. Figure out the cheapest possible thing, the crappiest MVP you can get out there within a week or two just to see how things go,” says Lin. “That could be a really janky prototype, a small Chrome extension, or a landing page. Anything where you can put it out into the world and see if there’s a response.”

Contrast that with enterprise, which is more about customer discovery. “With enterprise, building often isn’t the hard part. It’s all about selling. You need a shortcut to figure out, ‘Am I making something people want?’ Do a bunch of interviews with experts or potential customers to find out. Customers will tell you what their problems are. If you listen very carefully, you might be able to figure out a jumping off point to build a company around.” Here’s a sampling of the specific questions Lin and her potential co-founders asked in these customer calls:

- How do you currently manage this process?

- How big of a pain point is it for you, compared to other pain points you have?

- If you could wave a magic wand and have that problem go away, how would that affect your work or your customers?

When you’re exploring enterprise startup ideas, you have to get out and talk to customers. My co-founder and I got ideas from those conversations that I could have never come up with on my own in a million years.

7. Don’t be afraid to let your idea simmer for a while.

“I see so many founders starting companies saying ‘There’s an opportunity in this space somewhere, I’ll find it.’ Or, I've known kids just out of school who announce that they’re ‘off to do a startup.’ That might work out eventually, but it’s a hard thing to do because there’s no clear path,” says Lloyd Tabb.

“I waited a really long time to start Looker. Looking back, I think we had a lot of success because I waited until I had a crisp thesis on what the problem was — and then we went directly at it. I may not have been sure how I was going to achieve it, but I was clear on what the mission was from the jump: to build a product that lets everyone in the organization see everything that’s happening, through data."

Future founders, start with a really strong thesis on the problem you’re going to tackle. If you’re missing that first crucial ingredient, it’s best to keep your company building dreams on a low simmer while you work to figure one out.

That thesis took root in Tabb’s previous experiences. “I’d seen the need for a product like Looker over several years and kept returning to the idea. After playing founding roles at multiple companies, I knew that businesses needed a real-time understanding of their data. I was always building these one-off, custom tools to help others look at very narrow, specific datasets and I realized that there had to be a much better way of doing this,” he says. “If you’re building the same thing over and over again, that’s a signal that there might be a startup idea in there.”

8. Focus on the best jobs to tackle.

After grad school at Stanford, Sunita Mohanty found herself in the middle of her first startup, a failing K-12 analytics company. “We were stuck in circles of decision-making and couldn’t successfully execute or build traction. Looking back, it’s easy to diagnose that we had a hard time focusing on which problem to solve first because we didn’t understand the actual problems of our audience well enough — we only assumed we did,” she says.

Now in her work as an angel investor and advisor (in addition to her day-job as Product Lead as a part of Facebook's New Product Experimentation) she sees teams run into this very same brick wall, and always dishes out the same advice: “Do the work to make sure you are building a product that people will actually find valuable. That requires an incredibly deep understanding of the user, their hopes, and their motivations, instead of taking the easier path of operating off of untested assumptions.”

The bottom line is that you can very easily build something, but to increase your chance of creating something that is solving a real problem you need to be more rigorous in your approach.

To add that dose of rigor to her own work, Mohanty has come to rely on the JTBD (jobs-to-be-done) framework. (We’re just highlighting the relevant bits here, but for an excellent primer that’s tailored to the startup context, be sure to read her full JTBD guide on The Review.)

More specifically, Mohanty leans on jobs to be done statements, which concisely describe the way a particular product or service fits into a person's life to help them achieve a particular task, goal, or outcome that was previously unachievable. She shares the JBTD statement template that she finds helpful and is commonly used amongst Facebook and Instagram product teams:

When I…… (context)

But…… (barrier)

Help me…. (goal)

So I….. (outcome)

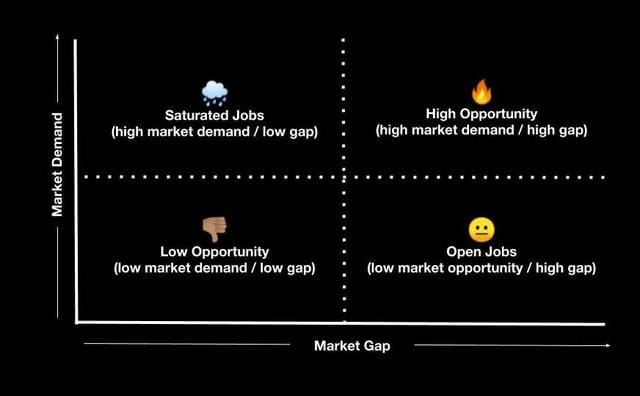

But of course, there are many customer goals your product could tackle, so focus is paramount here. “From user interviews, look for themes that emerge in jobs to be done. You can also run surveys that ask users to rank the importance of jobs and how well each job currently is served by another app or product to gain a better understanding of the market opportunity. This can help you to narrow down jobs and prioritize those with the most demand and the largest gap to be filled,” she says.

Mohanty likes to use this framework when thinking about which jobs to tackle:

9. Get super specific.

Bob Moore's first brush with life as a founder started in 2008 — three days before Lehman Brothers collapsed. Since cutting his teeth as a first-time founder in turbulent times, he's gone on to build two other companies. "The difference between having a crisp vision and muddling through without one will alter the trajectory of your company — I’ve been on both sides of that coin,” he says.

Here’s his advice for future founders hoping to come down on the right side: “Plain and simple, here’s the formula you need to nail down: Here's what we’re here to do, here’s why we'll be the best at doing this very specific thing, and here are the tailwinds that make now the right time to do it,” says Moore.

“We’re seeing this now at my current startup, Crossbeam. We started this company with an extremely specific vision for what the world should look like when this data collaboration problem is solved in the best possible way, not with something generic like ‘Partnerships are a pain, let’s go figure that out.’”

What are we going to do? What is our unique vision behind it? That’s an existential, table-stakes prerequisite to building a resilient venture-scale company. Even with the best team in the best market, you’ll hit a ceiling without these ingredients.

EVALUATE IF AN IDEA HAS LEGS:

10. Pressure test your idea against these four dimensions.

“Aside from choosing your co-founder, identifying the right market to go after the single most important decision a founder makes, and it’s one too many get wrong,” says Todd Jackson. As a partner at First Round, Jackson has tons of patterns from his career to pull from here. He’s been an exec at Dropbox, a PM at Google and Facebook, and a founder himself (of Cover, an Android startup acquired by Twitter in 2014).

One pitfall is that product managers-turned-founders tend to dive straight into execution mode. “They think of an idea, move quickly to building a prototype and then sometimes momentum and the excitement of building takes over. While the operational focus and pure execution that you picked up as a PM are huge strengths, you’re better off first taking a step back and thinking about whether the market you’ve chosen and the problem you’re solving is big enough,” he says.

But how exactly can you size up if a startup idea is worth pursuing? When Jackson left Facebook in 2012, he ran into the very same question. “My co-founder Ed Ho and I knew we wanted to do a startup. We knew we worked well together from our time at Google, and that we were really interested in the same consumer spaces. But what we ended up pursuing — what became Cover for Android — was actually our third idea,” Jackson says.

“Our first idea was in the sports space. We designed some things, talked to a bunch of entrepreneurs who had done sports related stuff and we realized that it was a hard market to compete in. Our second idea was a photo sharing app. At the time, Instagram was popular but not dominant, and Snap barely existed. There were still a lot of interesting things I think to be done there, but ultimately we were talked out of it by investors who were like, ‘Even if this is the next great photo app, how are you going to convince anyone of that? Not just users, but the engineers you need to recruit and so on.’”

To pressure test ideas like these (and the one that eventually one out), Jackson and his co-founders relied on the following framework — one that he still coaches future founders through to this day. If you’re an aspiring founder (or just keep a running list of company ideas in your Notes app) assess startup ideas against the following criteria:

- Functional needs: Does it address a clear functional need that users have? This is often why they’ll try it.

- Emotional needs: Does it address an emotional need that users have? This is often why they’ll tell others about it, unlocking that viral word-of-mouth growth loop that’s so critical.

- Billion-plus market: Is it in a large, underserved market? Or in a market that can become large? This impacts everything from your ability to fundraise to who may be interested in acquiring you.

- Breakthrough UX: Is there something novel or unique about the user experience? Does it feel a little like magic when you use it? This last one isn’t strictly necessary, but it’s very helpful, and a lot of successful products had it when they launched.

“Most founders I talk with haven't thought about their idea this deeply. They have a high-level problem they want to solve, but haven't yet mapped it to the functional and emotional needs of their customers. This exercise forces you to name the needs, and then pressure test whether those needs are acute or if they're just nice-to-haves,” says Jackson.

If you think of ideas that simultaneously meet people's functional needs and emotional needs, while sitting in a big market and making use of a breakthrough user interface, that’s a recipe for a really good company.

11. Start pitching, but learn to sort through all the feedback.

“Write what you know” is a common piece of writing advice. Likewise, founders hear some variation that tells them to tackle problems they’ve experienced firsthand. Nat Turner has a different approach, and it’s worked twice before — with his first company, Invite Media, which was snapped up by Google in 2010, and with Flatiron Health, which was acquired by Roche in 2018 for $1.9 billion (both of which he started with his co-founder Zach Weinberg).

Turner’s entire process can be condensed into these key steps. Most crucially, instead of just researching the idea, or talking casually with others in the space, he immediately starts pitching — not to get investment, but to get feedback.

- Begin with a general space of interest and look for any seed of an idea

- Network like crazy in the industry and take introductions extremely seriously

- Create a deck and start pitching anyone smart and relevant you can find on the specific idea – and be sure to take meticulous notes and follow up

- Tweak the deck between every meeting and hack together a demo and start pitching (pre-sell software that doesn’t exist yet but will)

- Find a trusted group of advisors to discuss key learnings from the field and get feedback

- Continue to iterate as hard and fast as possible on the feedback you’ve received

Turner recounts the early days of Invite Media: “We pitched everyone. We pitched potential advisors, investors, potential customers, friends, everyone. I can remember hundreds of meetings we had.” After beginning to pitch the idea, Turner and Weinberg and their two other co-founders built a demo as fast as possible, as people have an easier time reacting to a product than an abstract concept. After endless meetings of pitching a video ad creation product, the feedback they received began to form a pattern that they could act on.

When Turner and Weinberg assessed an idea, they looked for a few key characteristics:

- Can this be a big business? Does the opportunity to build a billion dollar company exist in this space?

- Is this sustainable? Can this idea become sticky and last for a while?

- How scalable is this? How well does this business scale and how does this grow nonlinearly?

“Within four months of our initial video ad creation idea, we realized that it was going to be really hard, based on talking with people, to get enough ad inventory and to scale the demand,” Turner noted. They then built a Facebook app related to advertising and pitched it to more people, which after another round of feedback morphed into a universal buying platform for display advertising.

They began the process of building Flatiron the same way as they built Invite: by picking a generally interesting area, in this case health. Turner elaborates, “Our first idea was a second opinion site, and the second idea was a clinical trial matching tool, and the third idea was a business intelligence tool.”

The challenge with this approach of intensive pitching and listening is you get a tremendous amount of feedback. The market will tell you lots of things: some right, and some wrong. It’s your job as an entrepreneur to separate the signal from the noise. Turner explains, “If you're going to be successful as an entrepreneur, the biggest thing is being able to take in conflicting feedback from all these people, many of whom are jaded or have bad habits, and some who are spot on. You have to be able to sit there and distill that information into something valuable.”

The hard part isn’t coming up with ideas; it's distilling all the information you have, 90% of which will be crap, and finally figuring out what is the good 10%, recognizing that the good 10% may change rapidly depending on the industry.

12. Take your own temperature.

When he started Bowery Farming in 2014, Irving Fain had never worked in agriculture before. While he may have been new to the indoor farming space, he wasn’t a stranger to the twists and turns of being a CEO and founder. After helping build up iHeartRadio, he struck out to co-found CrowdTwist in 2009 — which assembled big logos founders would dream of like Pepsi, Sony Music, and the Miami Dolphins. But the company’s success wasn’t enough to keep Fain energized by enterprise software, and he left as CEO in 2014 (CrowdTwist would eventually be acquired by Oracle in 2019).

That’s why in the earliest days of spinning up Bowery, Fain was particularly rigorous in assessing ideas with a long-range lens. “SaaS on the farm is a great business. Precision agriculture is another great industry. But they didn’t capture my passion, my imagination and my enthusiasm. That component of the stew is incredibly important when you’re founding any business, because of how long and hard of a journey building a company really is,” says Fain.

He wasn’t the only one who had felt the sting of founder burnout. “I’ve seen friends get incredibly excited about an idea. They go out and they raise some money and then very quickly the excitement sort of evaporates. And now you’re stuck building this company that you’re only moderately interested in. As I was looking at and evaluating different ideas, even when I got more and more excited, I paced myself. It was critical to keep turning over other rocks,” says Fain. “The core question you should be getting to is, ‘Am I going to be excited about this in three years, in five years in seven years?”

I wanted to make sure that the excitement for the idea grew and grew over time. That in the great times, and in the difficult times, my passion, enthusiasm and real love of the problem and the business would persist.

Cover image by Getty Images / seb_ra.