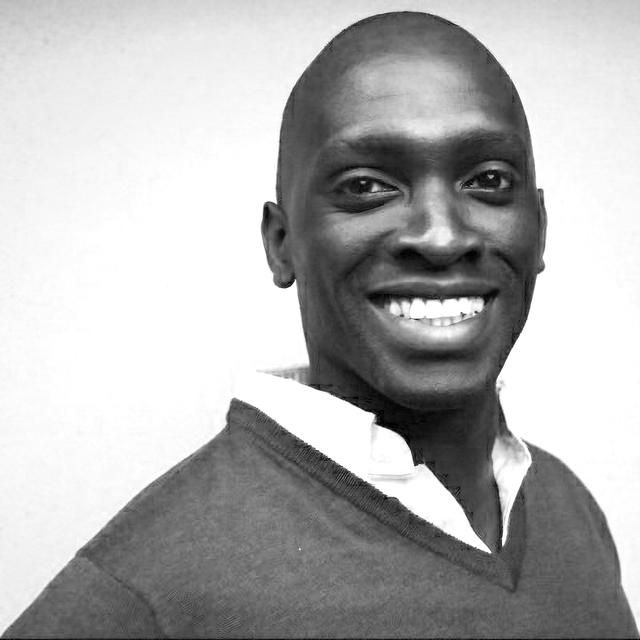

This article is a lightly-edited summary of the key takeaways from Ayo Omojola’s appearance on our new podcast, “In Depth.” If you haven’t listened to our show yet, be sure to check it out here.

While at Square, Ayo Omojola picked up a phrase from Brian Grassadonia (the co-creator of Cash App) that has stuck with him ever since: “going unreasonably deep” on a problem. Given that we just launched a new podcast titled “In Depth,” we thought this made for an excellent topic to explore with Omojola when he stopped by our virtual recording studio.

With Omojola as our deep-sea diving guide, we had a rich conversation about how this framework can be applied to the problem-selection phase of finding startup ideas and the art of shaping nascent products. Omojola has carved out a niche for himself in both of these areas, particularly when it comes to plumbing the depths of heavily-regulated spaces.

Currently, he’s the VP of Product at Carbon Health, tackling healthcare accessibility challenges such as COVID-19 testing. Before that, he was the founding product manager on the banking team for Cash App at Square, where he co-created the popular Cash Card and helped build out Square’s technical banking infrastructure. To round out his startup expertise, he’s also a former founder of a YC-backed startup and an active angel investor, which gives him a unique lens into finding and evaluating startup ideas. Whether it’s untangling the web of decades-old policy decisions or spending countless hours at a factory to learn the ins-and-outs of credit card manufacturing, Omojola’s got plenty of experiences to tap into — and a pile of hard-won lessons that he picked up along the way.

In this exclusive interview, Omojola shares some of those most critical learnings on what it really takes to build a product that cuts through the noise — like creating a credit card that unexpectedly goes viral on Twitter. We’ve distilled his mountain of expertise into four lessons on finding startup ideas, problem selection and the art of going unreasonably deep when building products — all of which will have you reaching for your notebook if you’re thinking about starting a company someday, or are hoping to help a new product take shape. Even if that doesn’t fit in with your career goals, there’s still plenty of wisdom to go around, including how to get better at hiring and managing folks capable of going deeper and moving faster.

LESSON ONE: CAREFULLY CHOOSE WHAT TO WORK ON BEFORE YOU START GRINDING.

To kick off the product-ideation process, Omojola borrows from an oft-repeated real estate adage: location, location, location. “My whole life, I’ve always been an ideas person. I have a running log that I’ve kept for 15 years that are just different ideas that I’ve had. I would say I’ve probably executed on 1-2% of them. Probably the truth is that most of them are bad in some way,” he says.

When it comes to a new idea, it’s so much more important to be certain, or as sure as possible, that the questions you’re answering are worth asking to begin with.

It’s a lesson he’s learned the hard way — after plenty of years spent burning the midnight oil on an idea going nowhere. “When I think back to my last company, I was co-founders with my brother and a friend. We picked a problem to tackle that we found really technically interesting. We cranked for years and worked so hard and it just didn’t matter,” he says. “The lesson I took from it was that we had put so much effort into the actual work, and had not put nearly enough effort into choosing what to work on. That was a much bigger determinant to our outcome — we hadn’t chosen a large enough market. If you pick a big domain that’s rich with opportunity, it of course matters how hard you work, but you also get so much more leverage.”

Omojola believes it starts with unlearning some of the lessons drilled into us from our school days. “What we’re taught when we grow up is that our outcome is 100% correlated to our effort. If I study hard for a test or work hard on a project, I’m going to get a better grade than if I don’t try. So I’ve always just assumed that when things aren’t going well, I just need to work harder. It’s ingrained a lot of habits, and I try really hard now to disabuse myself of that notion, because it’s not an accurate view of how the world works,” he says.

Choosing a problem that matters, even if your work is average, will generally yield a better outcome than choosing a terrible problem, even if your work is excellent.

“No matter how good you are or how hard you work, you are never going to be as powerful as forces of nature. If these larger forces in the economy or in the environment play out, and the thing that you’re doing is at odds with those, you’re probably going to get steamrolled. You’ve got to be mindful of what’s happening in the world at large, and how it affects what you’re trying to achieve,” says Omojola.

To find the problems that are both ripe for innovation and worth solving, Omojola leans on this theory. “I have a hypothesis that the age of the leading product in the industry, or the age of the fastest-growing product in the industry is a strong indicator. The older that product is, the more opportunity there is,” he says. “The types of problems that aerospace folks and natural resources folks are solving are hard science problems. But in domains like financial services, a lot of what you’re doing is business model innovations. It’s generally rare that your edge is going to be a scientific breakthrough, so the place where you can go pretty deep is in the regulatory domain.”

So how do you pinpoint those key insights? Like scouring an expansive beach with a metal detector, it’s not a perfect science. You can narrow down the general vicinity of where a treasure might be buried — but at some point you’ve got to just start digging.

“I have enough experience now where I can look at some procedural things and know, ‘Hey, there’s a dead end here, don’t go there.’ I can identify some broad areas of interest to poke around. I can probably go from looking at the whole landscape to narrowing it down to about 40% and cut out the areas I have a relatively high conviction are not worth spending more time on for whatever objectives I have,” says Omojola.

It’s a balance. You can go deep on any number of things, the real art is choosing what to go deep on. You have a limited amount of time and you have to be thoughtful about where you spend it.

“There’s just always some trial and error. You go down one route, it’s a dead end. You’ve got to stop and altitude shift, and then go down another route. It’s all part of the process,” he says.

LESSON TWO: FIND THE OPPORTUNITIES WHERE IT’S EASY TO STOP — AND KEEP GOING.

For Omojola, going unreasonably deep in regulated industries has taken him from credit card factories to debating the Durbin Amendment (TL;DR: it slashed the fees stores paid to banks whenever a customer swiped their debit card) with Square’s legal team. Along the way, he’s developed a rule of thumb: “It’s important to not be afraid to go to whatever depth necessary to get an answer that you really understand.”

Always look for those opportunities where it’s easy to stop, where it gets tedious. That typically is a signal that somebody or a bunch of people just haven’t gotten deeper before.

When you land on a problem and a market that’s remained stagnant, you’re giving yourself a massive head start out of the gate — but it doesn’t come easy. “When you’re working within domains that are regulatorily complex, generally, once you establish a beachhead, there are higher barriers to entry. That complexity is a reason that people don’t tend to try it,” says Omojola. “For years, the core advantage Cash App had was that for a long time in the U.S., if you wanted to move money from Bank A to Bank B instantly, Cash App was literally the only way that you could do it. The other options were either paying to use wires or using ACH, which was free but would move money slowly,” he says.

“That insight came from quite a bit of imagination and a team of people that spent years at Square banging their heads against the wall, working with card networks, and realizing that there was an unexploited mechanism for instant money movement. It happens to be the case that nobody’s using it this way because it’s a slog to pull it all together,” he says.

But even if you’re not coming up with a brand-new innovation like Cash App, there are plenty of other avenues to exploit to pull ahead from the pack. “Focus on what utility you can provide. How can you make something sufficiently more useful than the state of the art so that it cuts through the clutter, and the people who you’re trying to make stuff for actually pay attention?” says Omojola.

While Cash App had unearthed a cash cow with free instant money movement, Omojola’s Cash Card team was tasked with bringing to life another product line that wasn’t quite so original — a debit card — and spotted an opportunity to play with the intangibles. “When we were first working on the Cash Card, the state of the art in the market was not really impressive in any real way. Physical cards hadn’t really been played with in a really long time. That left an opportunity — nobody cared or thought that the aesthetic appeal would matter,” he says. “Sure, making something 10 times cheaper is compelling. But I think that sometimes just having something that’s beautiful or cool or feels good actually makes a difference.”

But it wasn’t just creating something that looked cool for the sake of it — the aesthetics were centered around the target customer and what the Cash Card could solve for that group. “The demographic we were going after was the unbanked and the underbanked. The best-in-class products for them were products that I would describe as negative status-signaling. Imagine if you’re out with friends and you pull out a random prepaid card that you bought at CVS. There’s a feeling associated with that in a way that a person pulling out a Chase Sapphire card does not feel,” says Omojola.

“Our underlying objective was to create a personalized physical card that people were proud to take out of their wallet and show their friends. We wanted to put the customer’s brand first, as an alternative to a prepaid card off the shelf which the brand has slapped their logo all over,” he says. But in following the unreasonably deep framework, this wasn’t as simple as firing up Photoshop and coming up with some wireframes.

Spot a yield ahead? Time to hit the gas.

“We spent an insane amount of time and effort optimizing for the look of the card. I spent probably a few weeks in combined hours at factories along with the lead designer of the product,” says Omojola. “You think a bunch of credit cards and debit cards all kind of look the same and have the same shape. But under the hood, there’s a whole industry of people manufacturing the cards. At one point, we literally tried 200 different combinations of thickness, power settings, et cetera, to get to the thing that we eventually shipped.”

The team wasn’t content to simply tread the path of others before — and wind up at the same destination. “The easiest thing to do would have been to send an email to someone and say, ‘Make the card look like this.’ The hardest thing to do was to actually understand all of the toggles. In a lot of cases, you look at those toggles and you think, ‘I’m not an expert on this, I have no idea.’” But for Omojola, that’s precisely where you have to dive deeper.

The dogged persistence to not accept the status quo paid off in a big way. “We ended up with a Cash Card product that thousands of people were excited to share on Twitter. Those were free impressions that we didn’t have to pay for that drove viral growth,” he says.

Question everything — and look for the “no’s” that come without a “why.”

Time and time again, Omojola’s seen people get stuck by asking the right questions — but not paying close enough attention to the answers. “It’s easier to take the thing that you’re told as fact. But there are enough cases where the thing that you were told is just a series of interpretations. The person telling you just got it from the person who told them, but it’s been a long time since someone’s really interrogated those assumptions,” he says.

When you’re looking at a problem with a heavy regulatory component, you have to be willing to question everything.

Omojola suggests you build up your own know-how on the topic — especially if you’re a novice — before looping in a few key allies. “You have to be willing to read everything on the topic from a regulatory perspective and build a perspective. Then I find a person or a group in the legal community that’s on your side to talk through it. ‘Hey, I read these things this way. Here’s how they might play out. What do you think?’ I actually try to do this as early as possible, because the legal community can give you shortcuts — ‘The question you’re asking was really already addressed here, go here and look at this thing,’’ he says.

Look out for this clue that you’re headed in the right direction. “A pattern that I’ve seen now a few times with both Cash App and Carbon Health is you’ll find an area that you want to go after and you ask, ‘Hey, can we do something else here?’ and people tell you no, but they can’t tell you why. Or the why they give you is so ambiguous,” says Omojola. “Probably 50% of the time you’re getting an ambiguous answer because you asked the question in the wrong way. But the other half is because that thing has changed. There are other ways that you could solve the problem, that the people that you’re working with haven’t necessarily encountered, or they’re not even aware that solution exists.”

To put it simply: technology moves a whole lot faster than governments do. “Early on at Cash App I can think of a handful of discussions where our legal team was sitting in a room with some regulatory guidance blown up on a projector. And we were just reading and realizing that a lot of this context was written years before the technology that’s available today became available,” he says. “The further you go from when the regulations were written, the more ambiguous they seem, because a lot of the time, the things that were available at that time have really changed.”

LESSON THREE: CONTEXT IS KING.

Going unreasonably deep can, at times, feel isolating. But the feelings that you’re on a solo mission are compounded when you don’t carve out the time to share your learnings and context across the team. “A lot of leaders fall into the trap of assuming that people are coming to the table with the same context as you. I now think that’s true much less of the time — in fact, it’s more often not true than it is true. Most of the time people just have very different contexts than what you have and their perspective on the objective is not necessarily aligned with yours,” says Omojola.

But as calendars fill up for the week, setting aside this critical block to get on the same page often falls to the bottom of the to-do list. Instead, time-crunched leaders revert to barking out marching orders. “If you’re busy, it’s a lot easier to say, ‘Hey, do this task.’ But it’s important somewhere along the line — and probably earlier, rather than later — to share a full picture. ‘Here’s what we’re trying to do, here are the areas we have a clear definition of, here are the areas that are more ambiguous,’” he says.

Sharing as much context as possible with the person you trust to get something done is like a superpower. It’s almost like downloading your brain into their brain.

But when it comes to the word “context” it can mean many different things, and there’s plenty of whitespace. Omojola’s framing for his team? “I find that it’s better to describe problems to them. Basically say, ‘Here’s what’s happening that we would like to change. Here’s some constraints that we want to put around it: We don’t want to spend X amount of time on it. It has to be above or below this cost threshold. Or it has to not break this other thing,’” he says.

But just like building up the lung capacity to dive deep on a problem, becoming more collaborator than drill sergeant is something Omojola’s learned over time. “I’m always problem solving. The instinct a lot of times, at least for me, is to go ask somebody for something with an idea of how it should work. When you’re trying to distribute context and narrative, I think it’s really important to enable people to come up with a solution for themselves and then debate,” he says.

You may save time upfront not taking the time to set context around what you’re trying to achieve, but you’ll more than add that time back on later when things get lost in translation.

Create cross-functional magic.

Beyond managing your immediate team, there’s a special alchemy that cross-functional projects — like creating a new prepaid debit card or standing up mobile COVID-19 testing clinics — require. “There are very often projects that require people from multiple specialties to participate — especially when you work at a larger organization, you’ll just have a lot more humans involved. And generally when these things happen, it’s not as though the person you need from the finance team or in accounting or security have a completely empty slate. They have stuff to do and are generally going to be busy as well. So getting them to prioritize what you’re working on can be complex, especially if you don’t have a personal relationship with them or if the project isn’t mission critical for them,” says Omojola.

Even more problems crop up when you’re working on a distributed team with misaligned schedules. “If you’re working with someone on the East Coast, you only have around four working hours a day when you’re both available. If you don’t have a problem solved by 2:00 pm on the West Coast, then you’re stuck until tomorrow,” he says.

“Now you’ve added this layer between when they are executing and getting blocked and waiting on feedback or additional context from you. This really compounds over time. Sharing as much of that context as possible as early as possible means you have less of those stalled interactions,” says Omojola.

To bring the best out of your group, you’ve got to be acutely aware of the most common minefields that crop up — like a lack of follow-through, or not getting the right folks in the room in the first place. “There’s an art to managing these big cross-functional group projects. I learned a lot from Emily Chiu, who led strategic development efforts for Cash App, about how to run a really efficient, seamless process. She would build out a grid and outline, ‘Here are the things that need to happen to make this thing come to life. Here are the objectives we’re trying to achieve.’ She would then have participants chime in and give them the opportunity to speak up about something that hasn’t been considered,” he says. “Also, a lot of times the person in the room speaking for a department isn’t the person who’s actually going to do the work. You’ve got to figure out a process for getting them to either delegate or report back on how they’re managing all the follow-ups.”

Never underestimate the power of a timeline — and a little sprinkling of public accountability — to move things along. “You’ve got to say, ‘Hey, you’re on this timeline, and the reason you’re on the timeline is these other things depend on you.’ At the check-in meetings make everyone aware, ‘The reason your thing can’t start is because this other thing hasn’t been done. How do we get that done?’ That kind of social pressure of the timeline can work wonders,” says Omojola.

LESSON FOUR: HIRE AND MANAGE WITH THE GOAL OF MAKING YOURSELF OBSOLETE.

When you’re going unreasonably deep and investigating previously-untapped opportunities, you need an incredible team to lean on. “I’m really enamored with the idea of hiring people who are better than me in every way possible. I want to create an environment where the people I work with do their best work and I leave them alone to just do it,” says Omojola.

I say this all the time to my team at Carbon Health: I want to make myself obsolete.

In the midst of hyper-scaling at Cash App, Omojla was strapped for time and watching once-important tasks slip further and further down on his to-do list. “My first instinct was to believe that I was inefficient, because I got super busy and a bunch of stuff stopped getting done. I figured that I just had to get more efficient and I started trying all these productivity hacks.”

But the problem was more complex than what email shortcuts could solve. “Looking back, the right answer would have been to replace myself everywhere as early as possible,” says Omojola.

“I am human and do have some insecurity. But I think it’s the right thing to do, and the organization is better off for it. The more that you give super smart people the environment to just kill it, the more the organization can run and execute without you in the room. And now you have the spare capacity to think through the areas of leverage that might not be getting taken care of,” he says.

Why you should hire former founders

Plenty of people say they want to hire people smarter than them, but very few actually do. Omojola leans on what he believes is an under-the-radar hiring secret to actually make this vision a reality.

“Coming out of YC and being a former founder, I have a lot of friends who were startup founders. I’ve noticed over and over again that you start a company and raise a bunch of money — and maybe the idea works and you have a great exit, maybe it doesn’t and you shut down. But either way, you’ve spent a lot of years just focused on one thing, and you have this incredible grab bag of skills that are more difficult to fit into a bucket for one specific role,” he says.

He noticed a pattern that these folks were somewhat viewed as riskier hires, rather than proven leaders. “I had all these friends who were incredible founders, and they would go for interviews at Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc. and always get bounced out. My perception of the problem is that a lot of companies are looking for a very particular profile. They might say a bunch of other stuff, but what they really want is someone who was a PM at Google,” says Omojola.

In the talent war, he knew he couldn’t miss out on this relatively untapped resource. “One of the things I’ve tried to do is to look for founders who are in transition from their last company and figuring out what to do next,” he says. “The nice thing about hunting for founders in transition is you don’t have to worry about whether or not they can ship. You have available evidence and public artifacts of their work that you can try independently.”

I think founders that have not necessarily had these massive exits are really undervalued by the job market.

But it’s not just companies that may be gun-shy about hiring former founders — the founders may be skeptical of joining a company where they’re not in the driver’s seat. “These founders in transition are in search of a mission and, like I did, they will have a chip on their shoulder and they’re going to want to build something new. I completely understand that they’re going to be flirty with ideas, and I want to support that,” he says.

Omojola sets the expectations early on in the interview process and — once hired — leaves space for the former founder to work their magic. “I state up front the purpose that I’m hiring for and the type of thing we want to do with the role, but I also try to create an environment where they have maximum creativity and flexibility. All I ask is that they’re transparent with me about how and when they’re thinking about what’s next,” he says.

When it comes to interviewing former founders, he suggests you focus your conversations less on the tangible what that they created, and instead start to excavate the why. “It’s very easy from the outside to look at a product and make a bunch of assumptions about how it’s constructed. I do this all the time,” he says. “But most of the products you use are a result of tradeoffs, architectural decisions, et cetera, that were probably relatively complex and in the weeds. I like to steer the conversation about why they made the choices they did so that I can get into their thought process.”

For leaders looking to dive into untapped depths, Omojola’s mantra is to get incredible people on the team, do an exceptional job building context and narrative, and then get out of the way. You’ll be able to map the route for your voyage together.