The corporate landscape is littered with jargon that’s all but lost its meaning from overuse — think “net-new,” “low-hanging fruit” or “boil the ocean.” Right alongside this graveyard of oft-repeated business speak? Strategy.

Sit in on a strategy meeting, and you might find yourself debating the company’s overarching mission, the goals with a new product launch, the metrics that are worth tracking, or a multi-year roadmap. The problem, according to Ravi Mehta, is that strategy has been stretched so thin to encompass any reference to long or short-term goal-setting.

As a product leader, he’s made it his mission to crisp up what it really means to dive into product strategy. Previously, he served as Tripadvisor’s VP of Consumer Product, where he scaled the product team from 7 to 70 and led launches that included hotel instant booking and trip planning. From there, he took on the role as Chief Product Officer at Tinder through early 2020.

With plenty of playbooks and hard-won lessons up his sleeve, he started sharing the wealth as an Executive in Residence at Reforge, which runs cohort-based programs aimed at helping startup folks level up. Here’s how he simplified product strategy’s definition for folks who joined his cohorts:

Product strategy is the connective tissue between what a product team is doing day-to-day and the company’s ambition.

In his time advising founders as an angel investor and mentoring product leaders as the founder and CEO of Scale Higher, a coaching platform, Mehta has found that fast-moving startups are hesitant to invest in this deep work. “Nobody wants to dedicate the time to think through product strategy holistically. The idea that you’re going to spend 2-4 weeks having these really wide-sweeping conversations is antithetical to how startup folks work on a daily basis. But if you spend a few weeks approaching this work in an intensive way, you’ll avoid doing a half-assed job over the next two years,” he says.

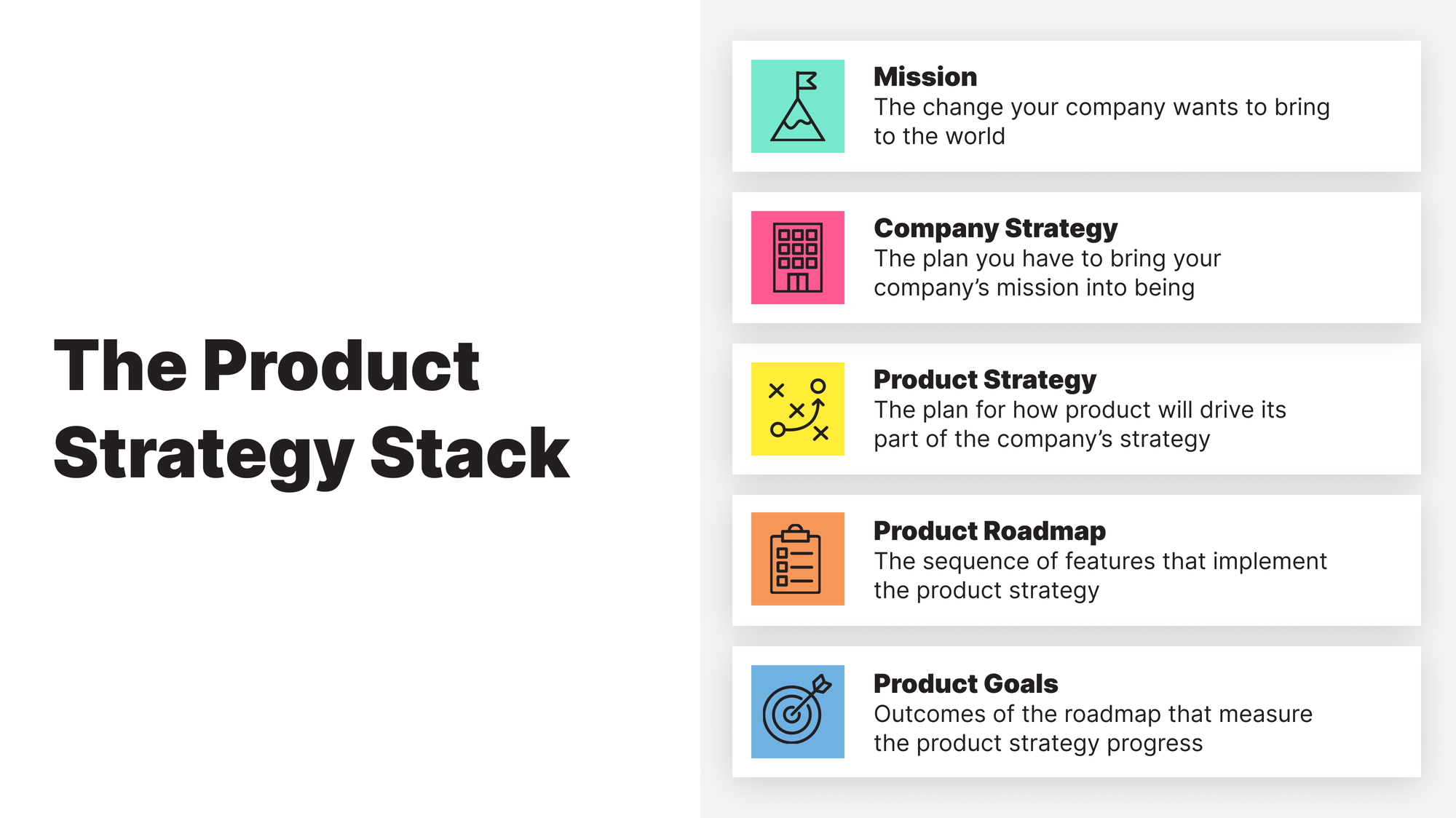

In this exclusive interview, Mehta dives exceptionally deep into product strategy, starting with the most common disconnect between the goals of a business and what product teams actually work on day-to-day. He outlines the “Product Strategy Stack,” which encapsulates the company mission, company strategy, product strategy, product roadmap, and product goals — bringing these amorphous ideas like “mission” or “vision” into sharper focus. He also shares his preferred alternative to OKRs, instead leaning on NCTs (narratives, commitments, and tasks) to stay on track with the product strategy. Let’s dive in.

DO YOU HAVE A PRODUCT STRATEGY PROBLEM?

Before excavating the key pillars of the Product Strategy Stack, Mehta flags a few common failure modes he sees from teams across the ecosystem — from early-stage startups still searching for product/market fit to larger orgs with a multi-product suite. Mehta leans on a set of high-level questions to frame the frequent disconnects between strategy and day-to-day execution:

- How are teams making decisions?

- How are those decisions manifesting in the product?

- Are most decisions aligned towards the short-term? Or are they laddered up to a long-term objective?

He points to three sneaky anchors that might be dragging down your product strategy momentum.

1. Goals ≠ strategy

“Especially today when there’s so much data to work with, I see a lot of teams underemphasize strategy and overemphasize goals — or they conflate the two,” he says. “You’ll sometimes hear: ‘Our strategy is to increase revenue by 5%’ or ‘Increase retention by 10%.’ That’s not a strategy, that’s a goal. It’s great if you can achieve that goal, but only if it’s actually part of a larger strategy that the company is trying to advance,” Mehta says.

“I often see teams get into a mode where they’re just doing anything and everything to move the goal, without actually realizing they’re headed in the wrong direction from a strategic standpoint to create long-term value.”

2. Product strategy should not exclusively live in the product org.

On the quest for product traction, Mehta also sees product leaders get stuck in tunnel vision. “As companies have gotten more product-oriented and product-centric, product strategy accounts for a really big percentage of the overall company strategy — but it’s not the whole thing. A product strategy needs to fit into the broader ambitions of the company. It needs to plug into what’s happening on the marketing, sales and technology sides. It’s one piece of a broader puzzle,” says Mehta.

Creating a product strategy without a thorough understanding of the company strategy is like going to the grocery store with a list of ingredients to buy, but without a plan for the recipes you want to cook.

3. Good strategy hygiene makes prioritization easier — not harder.

One of the key signals that startups have a product strategy problem doesn’t come from those big roundtable strategic discussions — it shows up in the day-to-day execution level. “The first thing that I look for is individual teams that are having a hard time prioritizing. As part of developing the roadmap, there will be questions that arise around should we do Feature A or Feature B? And teams have a hard time making that decision, not because of opportunity sizing around those features, but because there’s no context within which they’re making that decision,” says Mehta.

That lack of clarity quickly bleeds into the user experience. “When teams are optimizing for goals at the expense of strategy, you’ll often see a muddy UX. There’s a tendency to want to put more and more into the products to pull the user’s attention to the things meant to drive specific goals,” he says. “Ultimately, the overall product experience isn’t clear or elegant because there’s no thoughtfulness around where they want to draw the user’s attention so they’re getting maximum value from the product.”

Without a solid product strategy you end up with products that have a Vegas effect — there are so many flashing lights vying for the user’s attention because each team has its own isolated goals.

THE PRODUCT STRATEGY STACK: 5 STEPS TO STARTUP SUCCESS

In developing his frameworks to share in his Reforge course, Mehta teamed up with product pro Zainab Ghadiyali to put fuzzy concepts like “mission” into clearer focus. (Sidebar: Be sure to check out Ghadiyali’s Review article on designing a curiosity-driven career if you haven’t yet.) “I've thought a lot about how to divide the different elements of strategy into distinct concepts that progress from defining the mission and then ending up in a clear set of goals that are framed by that mission,” says Mehta.

The five components of what the duo termed the Product Strategy Stack include:

Mehta’s strong recommendation is to move through each piece of the product strategy stack in order. “Goals are at the bottom of the stack, not at the top, because goals should come from the roadmap, not the other way around. But that’s not how most companies work. More often than not, companies say our goal is to increase retention by 10%, and then the team will develop a roadmap to try to achieve that goal,” he says. “One of the things that the Product Strategy Stack is trying to solve is to take the emphasis away from the goals and put it more on what the team is trying to achieve.”

He leans on a favorite analogy to drive the point home. “Let’s say we want to go on a road trip from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. One of the goals or KPIs that we'll have on that trip is the number of miles driven — but that's not sufficient in and of itself for us to reach our destination,” he says. “We can drive 200 miles in the right direction — but we can also move 200 miles in the wrong direction. In both cases, we've achieved our goal, but we haven't necessarily made progress on the ultimate outcome that we wanted — which is to get to Las Vegas. So it's really important to make sure that goals are well-defined relative to the strategy.”

How to create stickier products with the Product Strategy Stack.

He also sketches out a story from his own product career that illustrates the Product Strategy Stack in action — and highlights how it smooths over some of the most frequent potholes product teams can come across along their route.

“Tripadvisor is an interesting example of a web1 business that has had fantastic durability over the years. The company was started in 2000 and was founded on the insight that people were going to move away from travel agents and make more of their travel purchases online. The founding team realized that if you go into a travel agent's office and asked to book a hotel, you're going to get three different brochures for your hotel options. They're going to be different prices, but all of the pictures are going to look the same because every single property is going to be presenting itself in the best light,” says Mehta. “There's almost no signal about why one property is more expensive than another — every single one of the brochures is beautiful and glossy. And so the insight at the time was that the internet will allow us to make that decision, not just based on what the hotels say about themselves, but based on the reviews and opinions of travelers all around the world.”

Tripadvisor’s company mission was to be an online destination where people could rely on the reviews and opinions of other travelers and ultimately plan the best possible trip. “Around 2016, as we were defining the product strategy map, one team was responsible for building out the trip planning functionality, which was a notoriously difficult problem. No matter how much value you provided to folks while they were planning their trip, their instinct was to go back to their notebook or their Google doc to compile all of their findings. Our product strategy was to create a trip planning product that would enable folks to plan their entire vacation on Tripadvisor,” says Mehta.

Before diving into the feature roadmap and the goals for trip planning, the Tripadvisor team carved out time just for heads-down planning. “We assembled a cross-functional team that included design, engineering and product teams to develop a product strategy document. We put together a 40-slide deck that included high-level wireframes of what the trip planning process should look like — not today, not in the next six months, but on a four-year time horizon,” he says.

Here’s how he differentiates this approach from the typical startup instinct: “The knee-jerk response would normally be to look at how many people were ‘saving’ places in Tripadvisor, and try to get them to save more places, and then try to ladder that up so that people could then take those saved places and create trip itineraries. Instead, we zoomed out,” says Mehta.

For starters, the Tripadvisor team surveyed over 700 customers to understand the trip planning process. “We had a lot of 1:1 conversations and found two really important insights. The first was that folks didn’t approach trip planning as a single-player activity. You’re often planning with a partner or a group, and other people need to be able to give their opinions. So we realized out of the gate from a product strategy standpoint, we needed to prioritize social sharing,” he says.

The second insight was that the trip planning tool needed to play well with others. “As part of the trip planning process, people weren’t just compiling lists of places on Tripadvisor. If their friend sent them a great list of things to do in Puerto Rico, they want to be able to add that to their plan. A travel plan isn’t just a collection of places, it’s a collection of all the different information a person has compiled about their destination. Our Trip Planning tool needed to be open, where you could add links and notes — if it was just a list of places you could go, that wouldn’t meet the use case and folks would just go back to using a Google doc,” says Mehta.

By starting from the strategic lens, rather than immediately jumping to the goal of increasing saved places by X%, the team took a longer-range approach. “Going deep with customers helped us define the strategic principles. Had we started with the goal we would have focused on acquiring a lot more people into the product, but that product wouldn’t be sticky with the level of retention that we were looking for to achieve Tripadvisor’s company mission,” he says.

TIPS FOR CRAFTING YOUR OWN PRODUCT STRATEGY DOCUMENT.

Even if your company already has a snazzy website with a mission statement or an annual plan that you think is good enough — Mehta’s recommendation is to start this product strategy exercise from scratch. “It's helpful to take a fresh look at every piece of the Product Strategy Stack, because oftentimes even if a company feels like they have a really good strategy, there may be gaps that the team is hitting on,” says Mehta.

Starting from first principles can sound incredibly overwhelming — but it’s an exercise that can pay incredible dividends. “I’ve seen some of the best startup product strategy exercises go from a completely blank slate to a really clear set of goals in 2-3 weeks if you stay intensely focused on the exercise,” he says.

Mehta advises using a sprint approach. “You start at the top of the stack, with the mission, and then you define each piece in order, all the way down to the goals for the next couple quarters,” he says. The key here is to not limit yourself by what’s been done before. “You don’t need to be tied to past work — in fact, you should shed any of the overhangs from your old product strategy process,” he says.

To make sure the org stays focused on the deep work required to tackle each pillar in the strategy stack, CEO sponsorship is necessary. “You want the founder or the CEO to lead the way here, and continuously reiterate that this exercise of defining and documenting the product strategy is the most important thing the company can do in the next couple of weeks — not hitting a specific goal or shipping some project,” says Mehta.

Another advantage of this rigorous approach? You’ll smooth the onboarding ramp for folks who join later on. “That three weeks will pay multiple years of returns in terms of clarity and focus for the company,” he says.

To capture the insights from the group, Mehta prefers to fire up a slide deck. “The product strategy documents that I’ve created at Tripadvisor and Tinder are typically anywhere from 25-40 slides, and most of those slides are wireframes that illustrate how the company can take the abstract, strategic ideas and think about how to render those ideas into an interface for the user,” he says.

Here are a few tips on how to structure your own slide deck:

- Start with the mission. “The first slide should always have a clear company mission — not how you’re going to execute the mission or measure it, but a clear, aspirational message that folks get emotionally excited about solving. The company mission is the most durable layer of the stack and the mission shouldn't be limited by execution considerations. A 10-person company can have as grand a mission as a 10,000-person company.”

- Bring in the customer. “Next, I recommend having 1-2 slides on the company strategy, which is the logical plan for how the company will achieve that mission. It clearly defines the sequence of steps your company needs to take, and it should account for the company's position in the market, unique strengths, and the set of situational risks and assumptions that factor into the plan. The company strategy should be durable for 1-3 years. You should also have one slide on the target user and the key use cases to make sure that strategy is tied back to the customer's needs.”

Oftentimes when crafting a strategy, the company focuses too much on itself and what it wants to achieve, and not enough on what’s best for the user.

- Sketch it out. “I recommend having 10-20 wireframes because really good product strategy isn’t broad and vague. It’s big, conceptual and ambitious — but also specific and concrete. It needs to be something that the team can execute. You’re not making decisions about where exactly certain buttons are placed or what the look and feel is, but instead you’re making structural decisions in a visual way.” Here’s an example: “One of the key considerations for mobile products is what are the 4-5 things that you’re going to have on your navigation bar — you can’t have any more than that, because there’s not enough physical real estate. So companies need to make strategic decisions around how to organize the product. What are the most important things to put in front of a user?”

- Start planning your roadmap. “List out your next 100 days with the initial sequence for how you're going to start to build towards the north star for what the product looks like.”

- Track your progress. “The final piece is the goals for the next quarter. How are you going to measure progress against your product strategy? But these goals don’t necessarily need to be metrics. They can be things like gaining a deeper understanding of a market, building out a particular feature or launching a feature.”

Who should you bring into the process?

Rather than sticking to a product-only huddle, it’s critical to connect the dots across the org. “Anyone who’s going to be touched by the product strategy — whether that’s design, engineering, user insights, data science, marketing, sales, etc. — should have at least one leader involved in crafting the product strategy documentation. Yes, that means there are going to be a lot of cooks in the kitchen. But ultimately a product strategy will succeed or fail based on the support across the broader company.”

It’s another reason why Mehta is such an advocate for using wireframes. “It forces teams to get design and engineering involved. It’s really important for folks to feel like their perspective has been integrated into the product strategy and that they’re involved from the get-go. Product leaders — make sure there are enough seats at the table for these different perspectives,” he says. And if you run into an impasse, Mehta’s advice is to lean on the CEO as the tie-breaker.

Get specific about what you’re *not* going to do.

Another piece of Mehta’s product strategy doc that you might not expect? Non-goals. “One of the hardest things that happen with these strategy processes is people come with their own expectations about what they want to see from the company and from the product. And when the strategy document is not specific enough, everyone walks away with a different opinion of what the strategy is, through the lens of what they think is most important,” he says.

“As part of the strategic planning process, you’re making choices. It’s important to document those concrete choices — not just that we’ve chosen to do A, but also to explicitly reinforce that we’re not going to do B,” he says.

In your product strategy document, be sure to include slides that outline what Mehta calls non-goals: “This should cover elements or questions that came up during the product strategy process that were particularly controversial. Be very clear about what decision was made and where folks disagreed but committed,” he says.

As product leaders, every choice we make is a choice that we save our users from making. If we're not clear about what we want our product to do, we shift that lack of clarity to the user.

“If we don’t decide the most important buttons in the app to use, our users need to figure out whether to click this button or that one. It’s really important to have a clear set of choices, make sure everyone in the org understands what those choices are, and deliver something that is clear and opinionated to the customer,” says Mehta.

NOT A FAN OF OKRs? TRY NCTs FOR CLEARER GOAL-SETTING.

With the product strategy document in place, the next piece of the puzzle is architecting a system for holding teams accountable to what they’ve committed to achieving. The most common framework leaders reach for is OKRs (Objectives and Key Results).

But over the years, Mehta’s found a few common snags to using the framework.

- Fuzzy objectives. “The way in which a lot of teams define objectives is not really tied back to strategy very well. Objectives are usually terse, just a few words, and they often don't look that different than key results.”

- Hyper-focus on metrics. “When crafting key results, teams focus a lot on metrics. This leads us down the path of treating goals as the destination, rather than strategy as the destination. That’s when you fall into the trap of trying to move the metrics by X%, rather than solving an important need for the customer.

- Aspirational thinking. “The other challenge that I've seen with OKRs is that the best practice is to set OKRs as aspirational. If 50 to 70% of the OKRs are completed, the quarter is considered successful. This makes OKRs probabilistic — there's a probability that certain things will get done at the end of the quarter — when what teams really want is a goal-setting process that's deterministic.”

Introducing NCTs: Narratives, Commitments, Tasks

With that framing in mind, Mehta unpacks the framework he developed to sidestep some of the most common challenges folks face with lackluster OKRs.

- Narrative: “The narrative is similar to the objective in an OKR, but teams are specifically recommended to make it longer. Describe the strategic narrative that the team wants to accomplish in at least a few sentences. Create a really clear linkage between the goal that’s being sent, and the strategy that goal ladders up to.”

- Commitment: “Each narrative will have 3-5 objectively measurable commitments. The word commitment is used very deliberately here — you should plan on achieving 100% of those commitments so that your team knows exactly what they’re expected to accomplish at the end of the quarter. Commitments are the evidence that the team has made progress on the narrative.”

- Tasks: “What work needs to be done in order for the team to achieve its commitments and make progress on the narrative? Tasks are the most fungible piece of a team’s NCT — the idea is to give teams a warm start on making progress on their goals. If at the end of a quarter a team has achieved all of its commitments, but none of the tasks — that’s a successful quarter. On the other hand, if a team completes all of their tasks but none of their commitments, that’s just checking the box. It’s not a successful quarter.”

Here’s a sample NCT using the previous Tripadvisor example:

- Narrative: Today, travelers who navigate Tripadvisor using Google are often leaving and re-entering Tripadvisor multiple times in a day. We can build a more retentive user experience by enabling them to organize, share and access all their trip content, no matter what device they are on, or where they are in their planning journey. As a first step, we’ll increase awareness and usage of the “saves” feature and new trip plan feature.

- Commitments: Increase the number of unique savers from X to Y by the end of Q1. Increase saves per saver from W to Z by end of Q1. Increase 7-day repeat rate for overall traffic (due to increased save usage).

- Tasks: Launch new backend saves service. Launch saves funnel health metrics dashboard. Test suggesting defaulting trip names. Single-factor test save icon

When it comes to goals and strategy — whether it’s working through your own Product Strategy Stack, or trying out a different approach to OKRs, Mehta’s final piece of advice is to be patient. “Teams want to be great at goal-setting out of the gate. If the first quarter doesn’t go exactly to plan, they often point the finger at the strategy process as the culprit. But that’s like going into a new workout program, doing a single rep of a new exercise and then saying, ‘That didn’t work! I didn’t build any more muscle.’ You’ve got to be consistent to really see the effects over the long term,” he says.

This article is a lightly-edited summary of Ravi Mehta’s appearance on our podcast, “In Depth.” If you haven’t listened to our show yet, be sure to check it out here.