Stuck in coach on a long-haul flight from Prague to New York in June 2011, Hubert Palan couldn’t shake the frustration weighing on him as a product manager. So rather than killing time watching movies, he passed the hours by brainstorming ideas to make his life easier.

“I was trying to do my job, but there was no tool of my own,” he says. “Jira, GitHub, and all the great software at the time worked for engineers but didn’t have what product managers needed: features for customer feedback and pain points. That made it difficult to build what mattered to customers.”

In a flash of inspiration, he jotted down the following statement: “I believe there is a better way of building great products and companies.” He even took a selfie to commemorate the event, as if he knew that in a decade, journalists would ask about the moment he conceived the brilliant idea that became Productboard — a $1.75-billion unicorn startup with more than 6,000 customers and 500 employees.

I just intuitively felt like something clicked in my brain, and got this emotional rush of dopamine from the eureka moment. I took a photo to remind myself later how excited I was about the idea — and to make sure it wouldn’t just end up like other ideas I never acted upon.

It seemed prophetic at the time, like he could already see the articles written about him that would need a photo to accompany his inspirational founder story. But the reality is, Palan knew nothing of the sort. That day, he was just another passenger daydreaming in coach class. Soon, his idea would fade into the background of his busy life.

“I did nothing about it,” he says. “I just sat on the idea.”

That is, until two years later, when the frustration of doing nothing about the problem became too much to bear.

“I became a VP of Product, and the company continued to be so distracted by shiny objects that we couldn’t stay focused long enough to build something great. Finally, I just said, ‘This is crazy. I'm going to start a company that solves this problem of product management so we have clear alignment, understand the customers and know what the pain points are,’” says Palan.

Understanding the problem

Before Productboard existed, product teams gathered customer feedback in a hodgepodge of ways: pasting a feature request from an email into a spreadsheet, or adding a bug report from a social media comment into Jira or Trello.

Like using a wrench to hammer a nail, these project management tools sometimes got the job done — but it wasn’t what they were made for. Often, the customer’s voice got lost in the shuffle. Users felt frustrated when they didn’t receive a reply, and product teams struggled to properly segment the customer base based on needs, prioritize requests, build effective roadmaps, and ultimately, craft products people loved.

“Product management is not engineering project management,” says Palan. “It's not about the tasks and milestones, where you break the solution into little pieces and then get it through the delivery pipeline. Product management is about the customers and their pain points, and then strategically deciding what you as the product team should focus on. For some reason, there wasn’t yet a solution built for that.”

Similarly, there was never a methodology or movement built for product management. Engineers had Agile. Designers had design thinking and Double Diamond. But what about product teams?

“The industry got to this point where it was clear to me that there needed to be a system of record for the product management organization, a tool that did something like Asana and Trello, something to manage tasks but with the added benefit of integrating the customer’s voice — like a CRM but for product.”

In January 2013, while still working at GoodData, Palan came up with the name "Productboard.” But to get his SaaS startup off the ground, he needed a technical co-founder. Being a solo founder isn’t for the faint of heart, and while Palan had studied computer science, he lacked sufficient coding skills to build the tool he was dreaming of. So, he put out a call for a great engineer on social media “for a friend.” “I was in the US on an H1B visa at the time, and couldn’t publicly reveal that I was moonlighting on a startup idea. If I lost my job, I’d have to leave the country,” explains Palan.

Software engineer Daniel Hejl saw Palan’s posts and reached out via Facebook, and in February 2013, joined Productboard as co-founder and CTO. The two had originally connected at a Startup Weekend event in Prague, where Palan is originally from. “Daniel was participating on one of the hackathon teams and I was a judge. Ironically, I voted against Daniel’s team and gave them the feedback that they lacked the technical chops to execute their idea,” Palan recalls with a laugh. “But we connected on Facebook and stayed in touch, so when he saw my post looking for a developer we hopped on a call and I revealed that the ‘friend’ I was referencing was, in fact, me.”

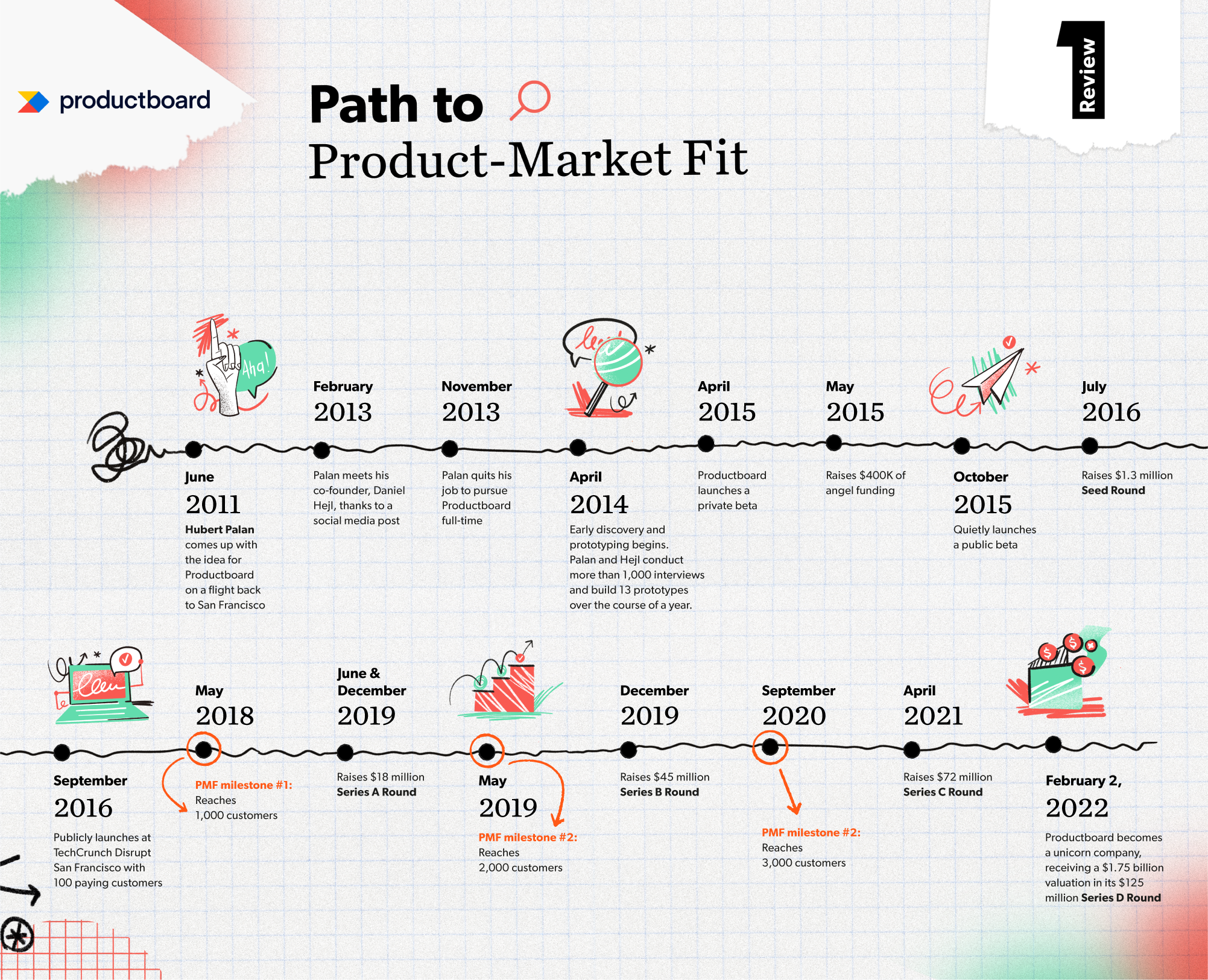

And just like that, Productboard’s path to product-market fit was set in motion.

Validating the Idea

Anyone can mine their personal experience for a startup idea, but it takes more than a hunch to build a successful business. While getting his MBA at UC Berkeley, Palan met Steve Blank, co-creator of the Lean Startup movement and author of “The Four Steps to the Epiphany,” and what he learned from Blank had a profound influence on the way he approached building Productboard.

“Steve Blank is always saying, ‘Get out of the building,’ meaning you have to go out and talk to people and test your product to see if customers want to use it. That really stuck with me, and it’s why I approached everything very systematically.”

Prototyping

Palan and Hejl spent April 2013 to April 2014 knee-deep in customer discovery and prototyping. Tapping into Palan’s Berkeley network, they conducted more than 1,000 customer interviews — from heads of product at small startups to the Chief Customer Officer at Twitter. What started as problem interviews gradually evolved into solution interviews, where they tested 13 different prototypes.

“This was pre-Sketch and pre-Figma, so I built a 250-page Keynote deck where I would do interactive slide walkthroughs,” Palan says of Productboard’s very first prototype.

To avoid wasting time on duds, the co-founders followed this framework: Palan built a super lightweight version of the solution on Keynote slides, and if people responded positively and the co-founders felt the idea had legs, then and only then, would Hejl spend time fleshing it out on the app-building platform Heroku.

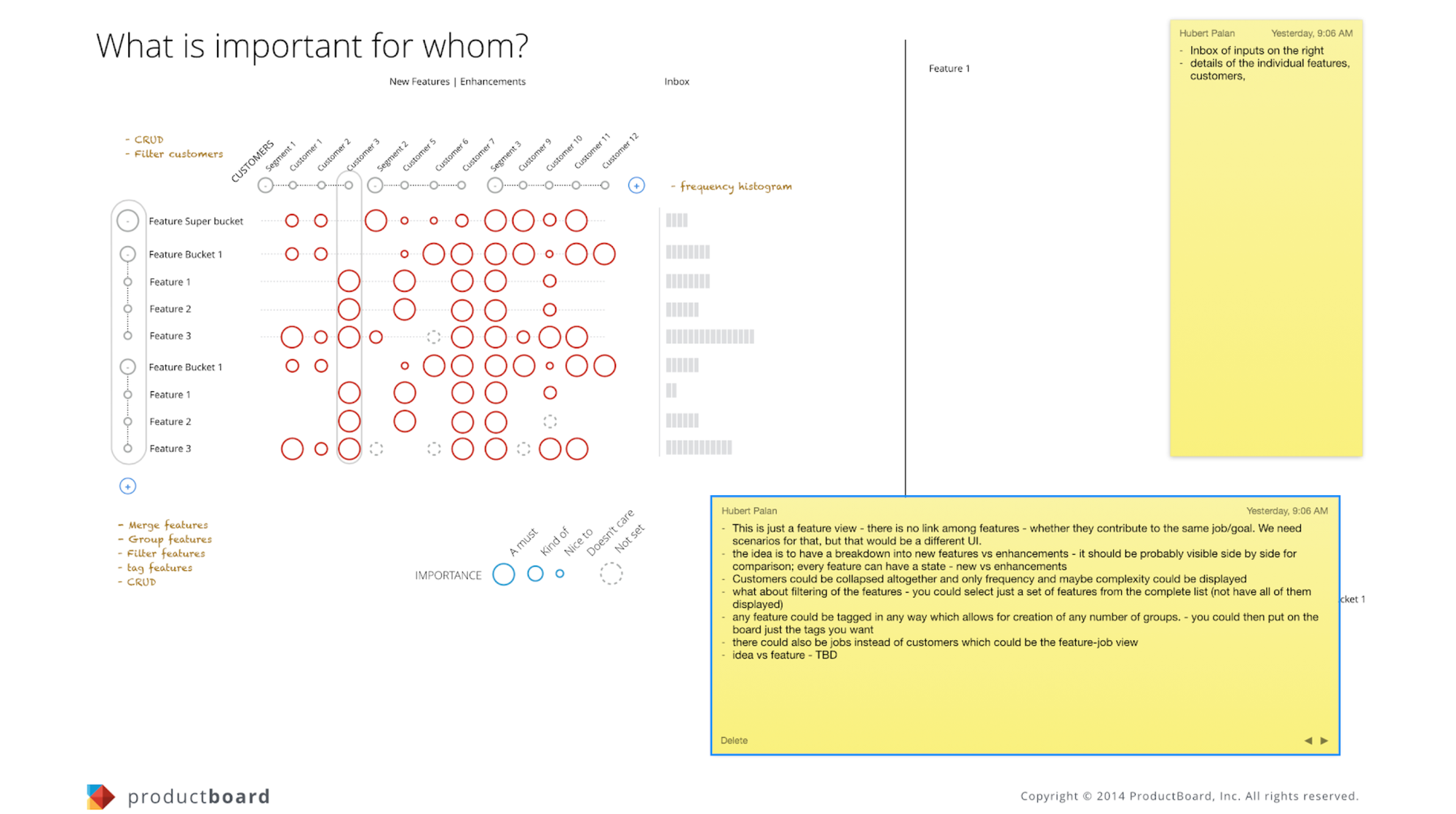

Each subsequent prototype experimented with a different feature, such as one where you could play around with customer segmentation, or another with a 2-by-2 prioritization matrix for customer ingestion and persona creation. With each iteration, the co-founders narrowed their focus based on customer feedback, and they learned a valuable lesson: Just because you’ve built a good product, doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to pursue it.

For example, they built one prototype based on the jobs-to-be-done framework. “And we learned that jobs-to-be-done is awesome, but very few people actually understand how to use it, so it was a niche that wouldn’t be the best entrance into the market.”

Another time, they came up with a sophisticated tool that helped product managers prioritize which features to pursue by segmenting customers and plotting which features were important to which segments—a true value add. But it turns out they’d built something too sophisticated for continuous use, meaning they’d struggle to get repeat users, and their product wouldn’t be scalable.

Here’s why: “Segmentation is absolutely a critical concept to understand in Product Management — the better you understand how different or similar people are, the better you can narrow down your focus. But once you understand segmentation and it clicks, you don’t need the segment visualization that much anymore — it becomes more of a nice-to-have feature,” says Palan. “It is similar to Alex Osterwalder’s business model canvas: You only need it at the very beginning of a new product idea, but it isn’t something that you’d use once you have a product-market fit already and need to keep building.”

In the beginning, everything is about focus. If you build a product that is mediocre for everyone and not really great for anyone, you fail.

And then, finally, they hit upon a prototype that got them one step closer to product-market fit.

“The first prototype to really resonate with customers was around the idea of prioritization supported by the voice of the customers. It was a use case that people were familiar with because they were doing it already in a spreadsheet, but it wasn't dynamic, it didn't scale, and it didn't have the right information. People really loved the connection between customer feedback and upcoming features, as in, ‘Customer X said something that shows they’d benefit from feature Y.’ It connects how the problem ties to the feature, which makes it easy for product managers to decide what to prioritize. And that finally clicked.”

But how did he know it clicked? Despite Palan’s preference for being analytical, when it came to deciding which prototype to pursue, he relied on something that’s impossible to quantify: gut feeling.

“There were emotional reactions like, ‘Whoa, this is amazing!’ These were moments of delight and surprise that I could feel,” says Palan.

In the early days, you don’t have quantitative measurements to lean on. So I relied on intuition that I developed through hundreds of conversations with customers.

Customer segments and personas

With the winning prototype decided, the Productboard co-founders knew what to build, but one piece was missing from their validation puzzle: Who were they building it for?

On the surface, the answer seemed easy. Palan was building the tool he’d always wanted, so in many ways, he was his target market: a VP of Product building a digital product at a startup.

But to have a deep understanding of his ideal customer, he adhered to Steve Blank’s “Customer Understanding” framework and started doing customer segmentation — a key component of finding PMF in the Lean Startup approach.

According to Blank, product-market fit is the “relationship between value proposition and customer segment.” They’d found their value prop (solution); now, they needed to find their customer segment.

To do this, Palan set out to identify the differences between the people he interviewed who had enthusiastic feedback about the winning prototype and those who did not, which led him to the following dimensions:

- Company size

- Product stage

- Digital-first or digital transformation

- Single product vs. multiple products

- Size of the product organization

- Care for the customer

- B2B vs. B2C

“I started to form this multi-dimensional model of the market and its different segments, and I made a very intentional decision that we were going to start with customers who fit the target profile of an early stage, digital-first startup with strong customer-centric, product-led culture, with one product team, building a single (ideally) B2B product. That helped me narrow the focus.”

By entering the market through this ultra-specific target profile, Palan and Hejl deviated from a common startup approach: casting a wide net in the hopes of catching a high volume of customers. Instead, Palan and Hejl set their sights on a small subset, where they were able to gain deep traction among a loyal audience before scaling up to large enterprises with multiple product teams.

But that was far into the future. For now, they needed to focus on their next step: beta testing.

Beta Testing and Launch

In 2014, armed with enough validation around their idea for Productboard, Palan and Hejl got to work building a beta. They put up a landing page where visitors could sign up for early access by connecting their LinkedIn profile and answering a few questions (like “What’s your company size?” and “Are you building a B2B or B2C product?”), which allowed Palan to match answers against the customer segment dimensions he’d identified. This ensured that he could select beta users who fell within the identified target market.

To generate pre-launch hype, they used grassroots marketing: posting to ProductHunt (shooting up to the #2 product of the day), distributing flyers at meetups, and pitching at the Lean Startup Conference (where Palan managed to connect with senior leaders like the Head of Product at GE — still one of Productboard’s customers today).

“I hustled like crazy,” he says, recounting the time his overzealous solicitation for signups got him kicked out of a product management conference. “The conference organizers got really mad that we were handing out fliers outside of the event even though we were not official sponsors.”

In April 2015, the co-founders slowly rolled out the beta to a handful of people who met the target market criteria, then 40, then 50 users. These initial beta testers got to use Productboard for free in exchange for giving the co-founders feedback.

One month later, Productboard nabbed its first investors, securing $400,000 in angel funding. And about seven months after that, the company started charging its customers, experimenting with different pricing models.

“I still remember how concerned I was about asking people for money,” says Palan. “We didn't know how much to charge, so I was like, ‘Let's try $20 and see what happens.’”

Eventually, the co-founders settled on a fixed fee for a feature set up to a certain number of seats. (Today, Productboard charges per seat.)

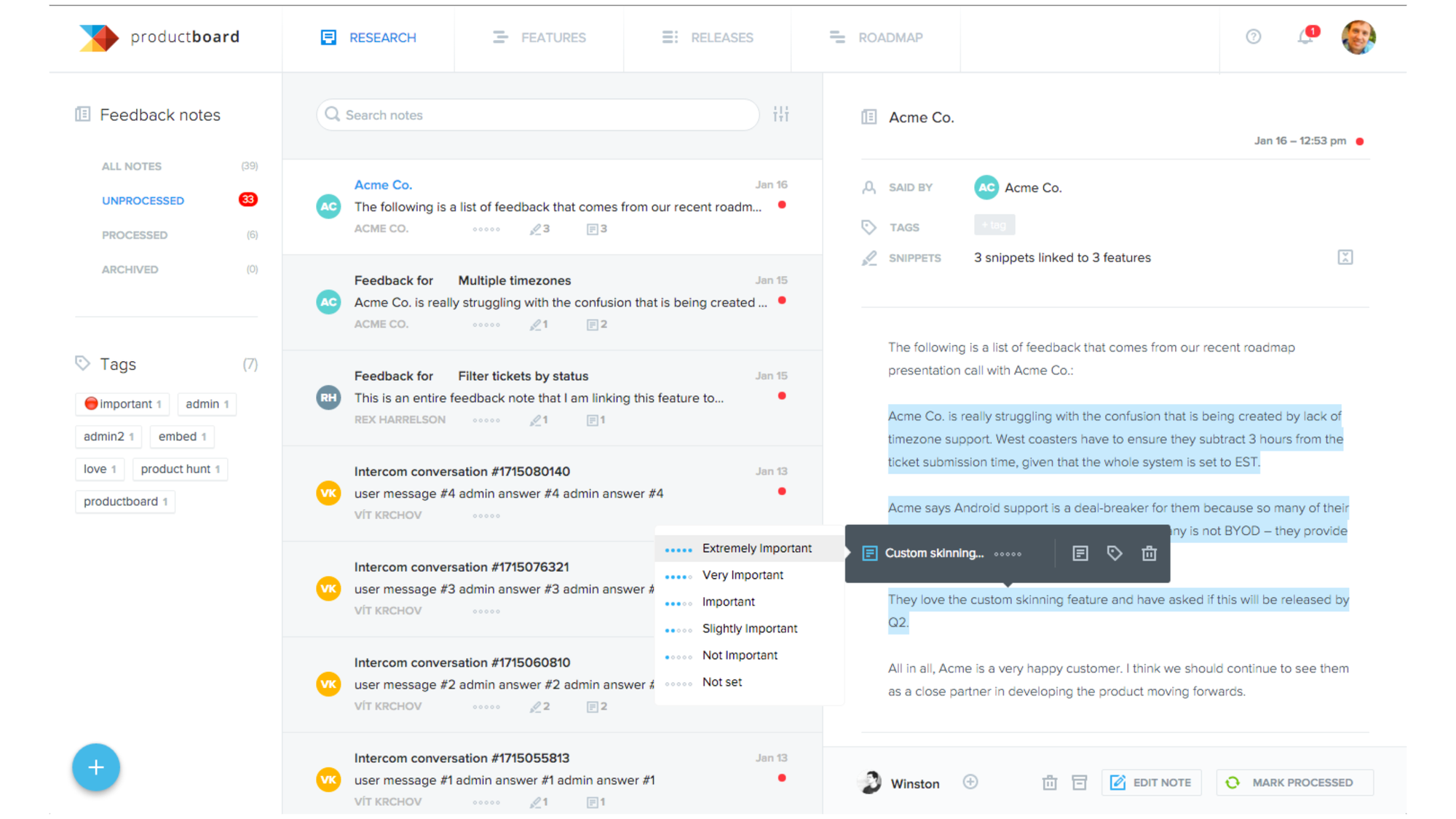

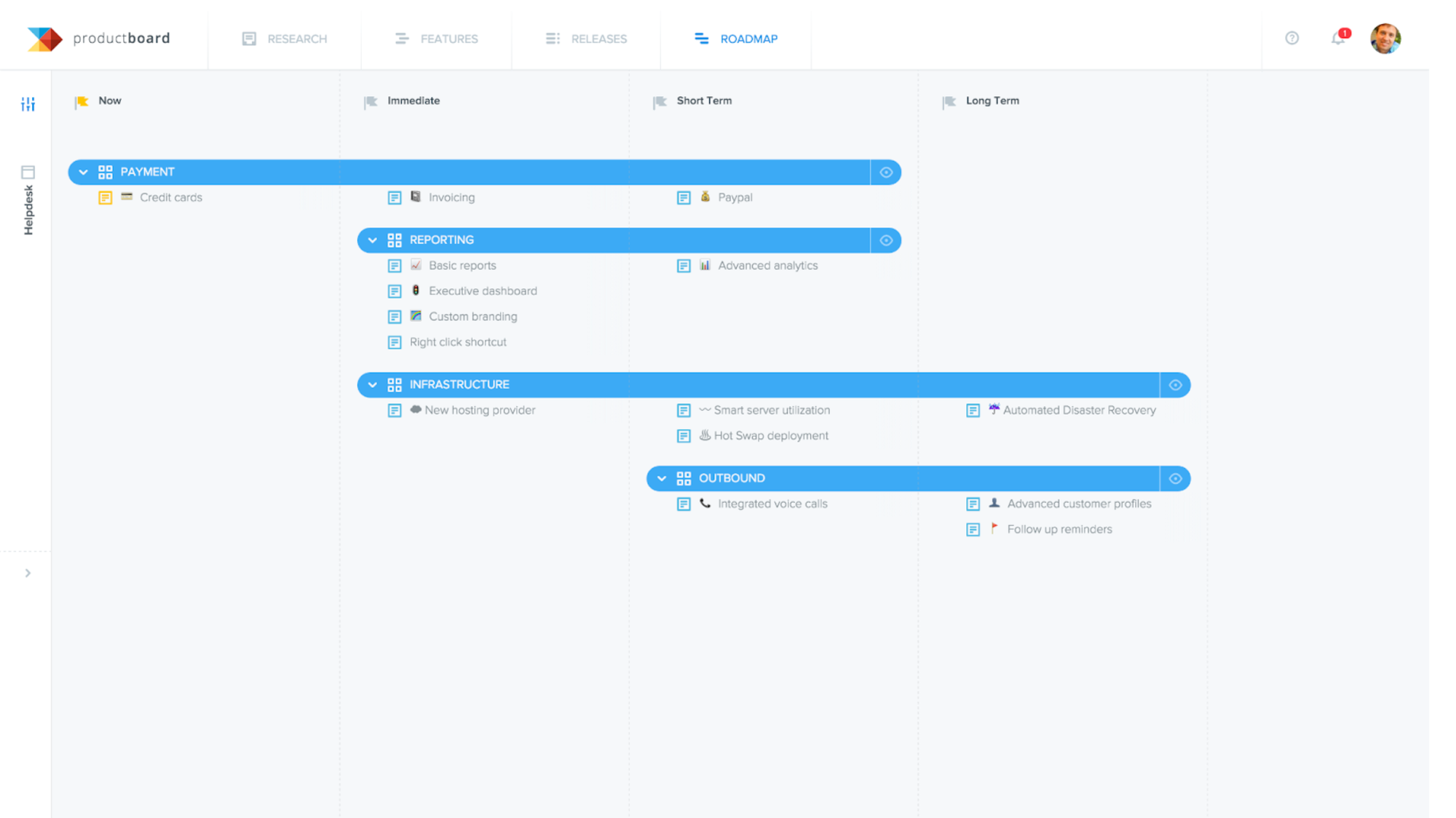

In July 2016, they raised a $1.3 million Seed Round, and right around the same time, their beta reached 100 paying customers and roughly $200,000 in annual recurring revenue. Productboard delivered on its promise to help product teams build what matters to customers. It did this by centralizing the feedback collected in various systems such as Intercom and Zendesk, linking those feedback requests to specific features on the product roadmap and then providing a user impact score so the business could rank the importance of each item.

That summer, Productboard was one of 25 companies selected for TechCrunch’s fiercely competitive Startup Battlefield, where founders pitch their products before a panel of judges composed of VCs and tech leaders for a chance to win $50,000. This would all happen at the Disrupt SF conference on September 12, 2016. With a hard deadline looming, the co-founders saw this as the perfect opportunity to do a final push and make this the official public launch of Productboard.

“One of the best ways to introduce a sense of urgency is to create a series of forcing functions: deadlines, milestones and goals with clearly-defined objectives,” Palan writes in a Medium article about the experience. “TechCrunch Disrupt was just the forcing function we needed. It forced us to tackle many of the things we’d been postponing. We fleshed out messaging and positioning, created a company narrative and defined our market category, updated our website, sought out a list of customer references, designed marketing collateral, created a demo project, improved onboarding, closed many product gaps, and, not to forget, actually told the world that we exist!”

Shortly after the co-founders' onstage pitch and corresponding TechCrunch coverage, Productboard saw a roughly 5,000% increase in trial signups and thousands of dollars in new MRR. On top of that, the exposure boosted their brand’s credibility, and several VC firms came knocking.

The Struggle to Find Product-Market Fit

For Palan and Hejl, there was a lot to be grateful for. Productboard had investor funding and enthusiastic customers, but with the hype of the TechCrunch Disrupt behind them, the co-founders now found themselves in that sluggish post-launch phase where product-market fit felt just out of reach.

The company was growing, but it wasn’t growing exponentially. Some of our investors were like, “Hurry up! You need to grow faster than this.” But I had to have patience. I told them that we needed to wait and build more features.

“At the beginning, we were intentionally focused on very simple product teams. Because if you can create a plausible hypothesis that there are enough people that fit your initial segment, your job is to go and find those people. If there aren’t enough people, then you have a problem because you don't have a line of sight for other bigger segments.”

To see if they were charting the right course towards eventual product-market fit, the co-founders focused on the obvious SaaS business metrics, such as ARR and churn, but also on engagement within the product: daily and weekly active users, as well as specific events that showed that the users were completing the workflow, such as the number of features prioritized with insights attached (the key feature that launched Productboard).

“We started to really gain confidence when customers were using our product regularly, and there was a regular conversation happening. We had an Intercom chat set up where we talked to customers and asked them what they wanted to see, and it created this close community.”

Sure, the buzz had been there earlier, even among the first 50 customers, but the company hadn’t yet gained enough critical mass to know if that was enough to stake a business on.

You can always find 50 people in the world who are going to tell you your product’s great—but that’s not enough to build a billion-dollar business on.

There were doubts about just how big the market was and investors questioned why no one else had built a product like this before. Were Productboard’s first customers just the early adopters, the “nerdy tinkerers,” as Palan puts it, who were few and far between?

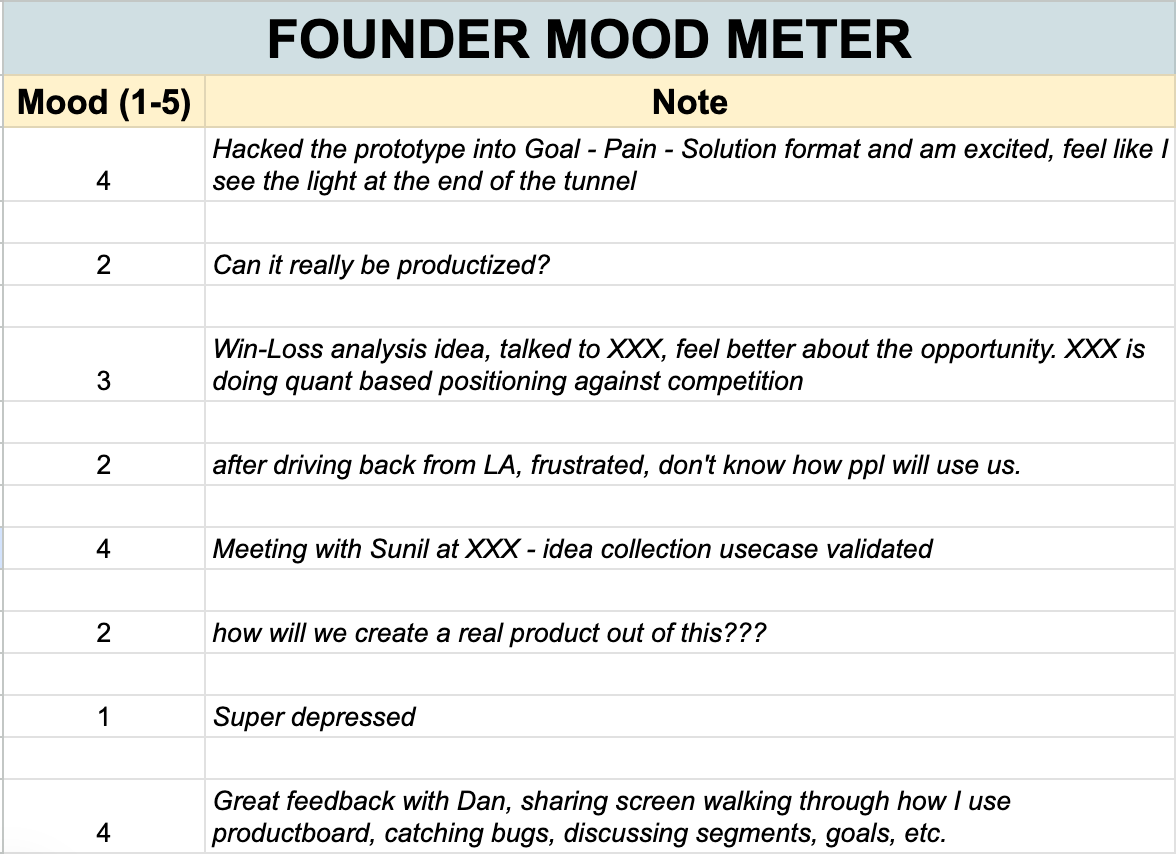

To cope with the uncertainty, Palan came up with an interesting practice. Using a spreadsheet, he plotted how he felt about the prospects of the company three times a day: morning, lunchtime, and evening, and called it his “Founder Mood Meter.” Below, he shares a snippet of some of his notes.

“I measured my own happiness as a proxy for the customer's happiness. At first, it was completely up and down. Eventually, I started feeling much better about where we were headed once the feedback became consistently more positive. It became obvious that there was a real market here — not just a few nerdy tinkerers,” he says.

And then, it happened. “We kept building the features, and eventually, the features became good enough for the jobs, and then suddenly, it was there: hockey-stick growth.”

It was a relief, but the work was just beginning. Palan wanted to build a lasting company, one that would expand to many use cases and be used consistently throughout the product management lifecycle.

“Eventually, the market started pulling us toward larger teams with different needs. And if we didn’t satisfy those needs, we weren’t going to unlock that market. So it was that market pull that led us to start building features for companies with multiple, larger product teams. “

How can a founder know when it’s time to pursue other use cases?

“If you have good unit economics — reasonable customer acquisition costs, good engagement metrics, healthy monetization and low churn for a specific segment — that shows you that you have a fit there,” says Palan.

While there isn’t an exact metric or score that can guarantee you’ve found product-market fit, in the product management world, it’s generally accepted that the LTV:CAC ratio can be helpful (customer lifetime value divided by customer acquisition cost). The higher the number, the better.

“If you get to 3X, or even 4X or 5X for the LTV:CAC ratio, you could say that's a healthy business, not just product interaction. If your funnel is so broad, your CAC and LTV are out of whack and your unit economics are not right, it's probably not a good time to go and expand into a new segment, a new use case or a new persona.”

Palan’s PMF Advice to Founders

Looking back on the past decade as a founder, Palan points to two pieces of advice he wishes he’d known about finding product-market fit:

1. Other things don’t matter.

“Be maniacally focused on product-market fit, and don't get distracted. In retrospect, I spent way too much time making sure all our legal stuff was buttoned up, and all the other things that you do as a founder, and looking back, it didn’t matter. Getting to product-market fit is really what matters, so get to that as quickly as possible—prove that this product is great and monetize the hell out of it. Ask yourself, ‘What is the critical thing that will get you there fast?’”

2. Don’t waste time on people who don’t understand the problem.

“When you're looking for product-market fit, identify the criteria of your target segment. Of course, you need to be curious and talk to some people who you don’t think are within your target segment, but you end up wasting a lot of time with people who are not the right people to talk to. You want to be kind and respectful, so you do the full-hour interview—and you shouldn't. You should just say, ‘Thank you, but it doesn't sound like this is a good fit.’

“When I was raising money, I wasted so much time with people who didn't understand product management. And then I met Ilya Fushman of Kleiner Perkins (one of our investors), who had been the Head of Product at Dropbox, and Ilya said, ‘Of course I get it. This makes so much sense.’ It was the easiest pitch ever.

As for “loss interviews” (when you ask a lost prospect why they didn’t choose your product), Palan isn’t a fan.

Time spent trying to figure out why someone didn’t choose you is time you could be spending finding the people who would choose you (assuming they exist).

Looking Forward

It’s been over a decade since Palan was 10,000 feet in the sky, scribbling those words about his belief in a better way to build great products — and since then, Productboard has helped more than 6,000 customers do just that. Marquee companies like Zoom, Salesforce and JPMorgan Chase use the platform every day to prioritize features and help teams align on product roadmaps.

Even with this overwhelming success, one question is always on Palan’s mind: What’s next? Since its latest round of funding — a $125 million Series D in 2022 — Productboard has continued to move upmarket, growing its enterprise customer base and scaling its product offerings, such as introducing AI features, to keep up with ever-evolving market demands.

It’s a good reminder for founders everywhere who are sprinting toward product-market fit: Don’t be surprised if you get there and find that the finish line has moved. “You might stumble into product-market fit initially and think, ‘This product took off! It's amazing.’ But you can’t rest on that. What's next?”

Product-market fit is not a single point in time. It’s a path that you need to keep walking on. The market changes as you expand the use cases and the capabilities, and you need to constantly balance that.

“Don't overbuild, don't underbuild,” Palan says. “The key is to develop the product management muscle to strike the right balance and continue to expand and adjust with the market.”