“If you write a book about feedback, you’re going to get a lot of it,” says Kim Scott. For Review readers, this name likely sounds familiar — when it comes to company culture and advice for being a better manager, Scott is something of a legend. Several years ago now she stepped onto the First Round CEO Summit stage to give a talk about her signature concept of Radical Candor — and she didn't expect both the video of her keynote and the Review article based on it to go viral. It racked up millions of views and quickly shot to the top of our all-time most popular pieces list. This deceptively simple yet incredibly powerful framework is still oft-cited in leadership circles and has become shorthand for effective management.

In 2017, she followed up the Review piece with a New York Times bestselling book, “Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity.” Afterward, she started a successful business, also named Radical Candor, which she founded with Jason Rosoff. The duo teamed up to offer coaching and interactive workshops chock-full of practical frameworks for embedding Radical Candor within all sorts of companies — from young upstarts to massive enterprises.

It was at one such workshop that Scott got her own dose of Radical Candor. “Shortly after I had launched ‘Radical Candor’ I was giving a workshop at a tech company in S.F. The CEO was an old colleague of mine, and one of too few Black women in tech leadership. Afterward, she pulled me aside and said, ‘I really like Radical Candor and this idea of care personally, challenge directly. But I gotta tell you, Kim, it’s much harder for me to put Radical Candor into practice than it is for you, and it’s probably harder for you to put it into practice than it is for the men you work with. As soon as I give someone the most compassionate and gentle criticism, I get the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotype.’”

As Scott puts it, she had several different realizations at the same time. “The first was that I had not been the kind of colleague and the kind of upstander that I wanted to be for her because I had never noticed that burden for her. It had never occurred to me the toll that must take,” says Scott. “Second, it made me realize that not only had I been in denial about the things that were happening to her, but I was also in denial about the things that were happening to me. Denial is a hard thing for the author of Radical Candor to admit to. Third, it made me realize the number of times that I had failed as a leader and as the CEO and founder of my own companies. I had failed to create the kind of work environment that was maximally productive and also fair — where everybody could just work,” says Scott.

It was a lightbulb moment — she could be on the receiving end of workplace injustice as a woman in the workplace, a bystander to other victims, and even a leader failing to right the ship when it was thrown off course. “I never wanted to see myself as a victim, but even less did I want to see myself as a perpetrator,” says Scott. The process of grappling with these realizations sent her on a path to write her latest book, “Just Work: Get Sh*t Done, Fast & Fair,” which was recently released.

Before “Just Work” hit the shelves, we got a sneak peek at its contents when Scott stopped by our (virtual) roundtable for a frank discussion. She was joined by Trier Bryant, co-founder and CEO of Just Work, which aims to help companies put the principles of the book into practice, just as Radical Candor the company did for the frameworks in the book “Radical Candor.” Bryant’s got a stacked resume of her own, holding leadership roles at Goldman Sachs, Twitter, Astra, founding her own DEI consulting firm, and serving in the United States Air Force as a Captain.

When it comes to DEI in the workplace, people often say, “This is a marathon, not a sprint.” But a marathon has a destination, then it’s over. This work is not that — this is work we need to be committed to for a lifetime.

With “Just Work” hot off the press, we share five lessons from its impactful pages and weave in additional insights from Scott and Bryant in our exclusive interview with the duo. While many column inches have been devoted to tackling the DEI challenges that plague every workplace, Scott’s superpower is giving us simple tactics and straightforward frameworks to put big, amorphous ideas like “inclusion” and “feedback” into practice. She also is willing to tell plenty of stories about times when she’s gotten it wrong. What follows is an essential guide that leaders and their employees need to create a more just workplace and transform careers for the better. Let’s dive in.

LESSON #1: WE ALL HAVE A ROLE TO PLAY.

“One of my favorite leaders in Silicon Valley, Alan Eustace, once stood up in front of his team, which was hundreds of people, and said, ‘If you are underrepresented and you’ve experienced bias or prejudice or bullying, just in the last week, I want you to raise your hand.’ It seemed like almost all the underrepresented folks in the room raised their hand,” says Scott. “Next he said, ‘If you’re not underrepresented and you’ve expressed bias or prejudice or bullying in the last week, raise your hand.’ Of course, nobody raised their hand. The issue is, we can’t fix problems that we refuse to notice.”

Despite the fact that DEI in the workplace has become an often-discussed topic, these conversations too rarely result in true impact. Why? In her long career working for companies like Google, Apple, and Dropbox, Scott says it often boils down to denial. “No leader I’ve ever talked to has said, ‘I want to create the kind of environment where I can coerce everyone.’ I’ve also never met a single leader who says, ‘I want to create an organization that demands conformity.’ We know that’s not going to create good results or produce innovation. And yet too often, that’s exactly what happens,” says Scott. There’s a reticence to examine our own roles. “How many times had I hired an entire team of all white men? More times than I’d care to admit,” she says.

The problem is not a lack of good intentions. The problem is that we often don’t want to notice the problem because it’s not clear to us what we are supposed to do to fix it. Once we clarify what our role and responsibility are, fixing the problem becomes more straightforward.

All of us want the kind of work environment where we can do the best work of our lives, and yet something gets in the way.

Here’s how Scott further explains these roles and responsibilities in “Just Work,” which we’ve summarized below.

In any instance of injustice you encounter at work, you will play at least one of four different roles: person harmed, upstander, person who caused harm, or leader. Each of these roles has its own responsibilities. As you consider these roles, recognize that they are not fixed identities. Instead, they are temporary parts you play. You may at different moments play all the roles. And sometimes, confusingly, you may even find yourself in two or more roles at once

- Person harmed — choose your response: If you’re on the receiving end of workplace injustice, your responsibility is first and foremost to yourself. This means remembering that you get to choose your response, even when your choices are hard or limited. Recognizing those choices, evaluating their costs and benefits, and choosing one of them can help to restore your sense of agency.

- From observer to upstander — intervene, don’t just watch: The word “observer” suggests passivity. If you witness injustice and want to help fight it, you need to be an upstander who proactively finds a way to support people harmed, not a passive bystander who simply watches harm being done, perhaps feeling bad about it but not doing anything about it.

- Person who caused harm — listen and address: It doesn’t feel good when someone tells you you’ve harmed them, particularly when that wasn’t your intention. But as with critical feedback of any kind, consider it a gift. Feedback can help you learn to be more considerate, avoid harming other people, and (at minimum) correct your behavior before it escalates and causes greater harm and/or gets you into serious trouble. Listen to what you’re being told and address it.

- Leader — prevent and repair: Creating a just working environment is about eliminating bad behavior and reinforcing collaborative, respectful behavior. That means teaching people not to allow bias to cloud judgment, not to allow people to impose their prejudices on others; it means creating consequences for bullying and preventing discrimination, harassment, and physical violations from occurring on your team. Workplace injustice is not inevitable.

For more on tackling bias, prejudice and bullying in the workplace, watch Scott and Bryant’s talk here and read on for more of our takeaways.

LESSON #2: WE NEED A FRAMEWORK TO GO DEEPER THAN UNCONSCIOUS BIAS.

Unconscious bias has become a buzzword — almost certain to come up in any surface-level discussion about DEI in the workplace — and plenty of well-meaning companies rolled out training. But Scott and Bryant have seen far too many companies consider unconscious bias training the finish line, rather than the starting block.

“Bias awareness training can be helpful in rooting out unconscious bias when it’s done well by people who understand the issues deeply. But in practice, it often feels like a sort of ‘check the box, cover your a**, protect the company from legal liability, but don’t actually try to address the underlying problem’ exercise,” says Scott.

Simply requiring everyone to go to unconscious bias training, even a great one, won’t be enough. No training can possibly change deeply ingrained patterns of thought. Disrupting the bias is key.

Scott believes we’re also missing out on critical conversations by slapping everything with the “bias” label, rather than face some harsh truths. Discrimination in the workplace can stem from bias that creeps up, but it can also be prejudice, or even escalate to bullying. “This was my aha moment when I was reading the book, and what made me really excited to join Kim to build this company. Far too often we try to lump all three of these together as if they’re the same, but they’re really not,” says Just Work co-founder and CEO Trier Bryant.

There’s a clear throughline between “Just Work” and Scott’s previous work with Radical Candor, which gave us a vocabulary to discuss the spectrum of feedback with terms like Obnoxious Aggression and Ruinous Empathy. “‘Just Work’ became a tool to name my different experiences. More importantly, it outlined actionable tactics on what I could do as an individual and a leader,” says Bryant. “Kimberlé Crenshaw says, ‘You have to name it in order to solve it. So step one is how do you name these workplace injustices and the root causes so we can identify the solutions?”

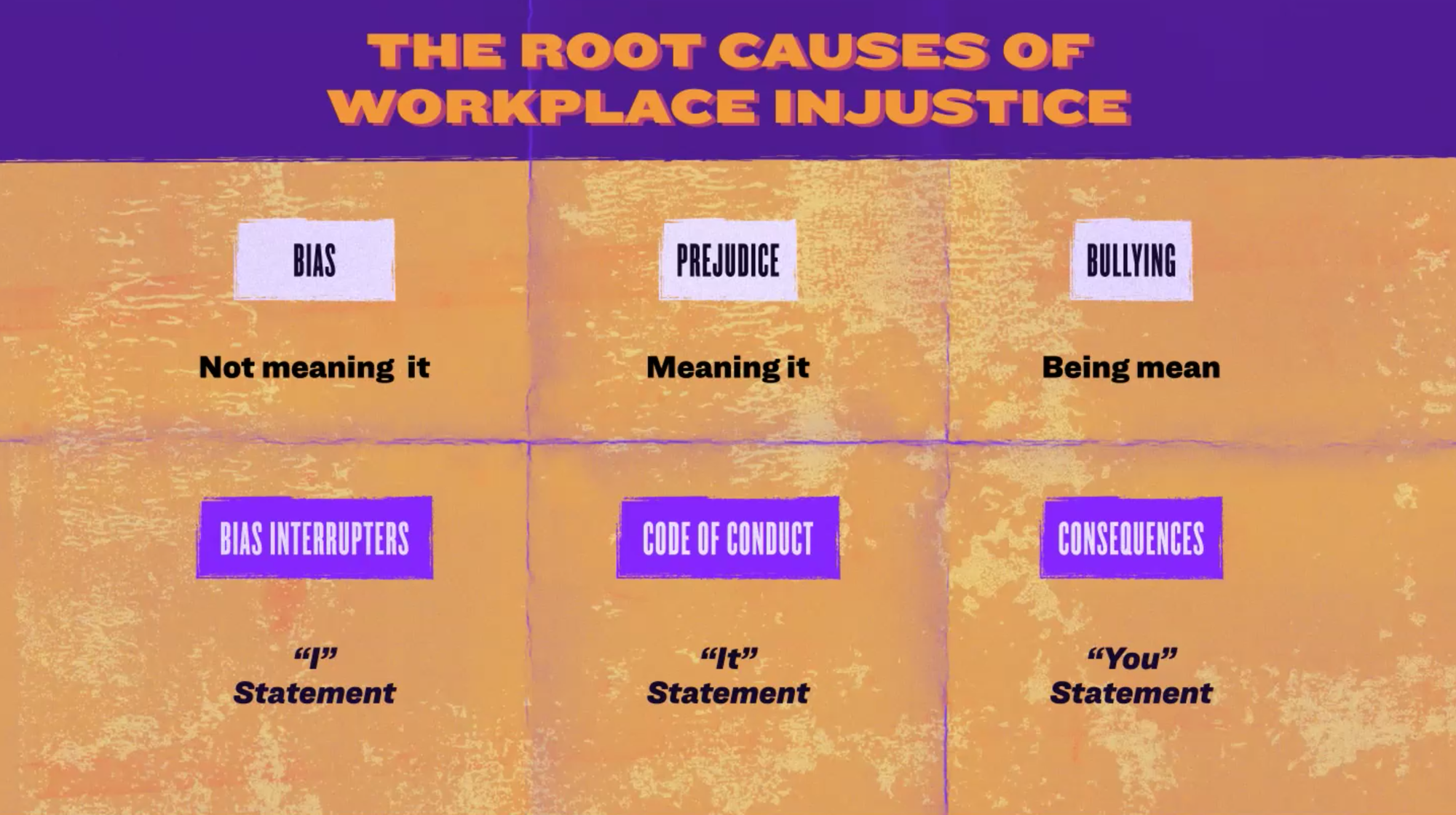

Returning to the pages of “Just Work,” here’s how Scott further sketches out the root causes of workplace injustice.

- Bias is “not meaning it.” Bias, often called unconscious bias, comes from the part of our mind that jumps to conclusions, usually without our even being aware of it. These conclusions and assumptions aren’t always wrong, but they often are, especially when they reflect stereotypes. We do not have to be the helpless victims of our brains. We can learn to slow down and question our biases.

- Prejudice is “meaning it.” Unfortunately, when we stop to think, we don’t always come up with the best answer, either. Sometimes we rationalize our biases and they harden into prejudices. In other words, we justify our biases rather than challenging their flawed assumptions and stereotypes.

- Bullying is “being mean”: The intentional, repeated use of in-group status or power to harm or humiliate others. Sometimes bullying comes with prejudice, but often it’s a more instinctive behavior. There may be no thought or ideology at all behind it. It can be a plan or just an animal instinct to dominate, to coerce.

LESSON #3: HOLD UP A MIRROR TO BIAS WITH “I” STATEMENTS AND BIAS INTERRUPTERS.

Building more diverse and inclusive teams is (rightfully) top of mind for plenty of companies — particularly in tech. But hiring a bunch of talented folks from other backgrounds is just the first step. “As you start having more diverse teams, your proximity to working with people that have different identities and different intersections than you is going to increase the amount of bias that can creep up in those situations,” says Bryant.

Tips for individuals: The “I” statement.

To confront bias in the moment (we’ll get into other types of workplace injustice later on), “Just Work” recommends leaning on “I” statements for productive conversations. Here’s why, via an excerpt from the book:

If it's bias you’re confronting, whether you are the person harmed or the upstander, your goal is to invite the person in to understand your perspective. Easier said than done. Quick rule of thumb: even if you don’t know what to say, start with the word “I.” Starting with the word “I” invites the person to consider things from your point of view — why what they said or did seemed biased to you.

The easiest “I” statement is the simple factual correction. An “I” statement can also let a colleague know you have been harmed without being antagonistic or judgmental. For example, “I don’t think you meant to imply what I heard; I’d like to tell you how it sounded to me...” An “I” statement can be clear about the harm done while also inviting your colleague to perceive things the way you do or to realize that an incorrect assumption was made.

Below are more examples of the sorts of “I” statements you can use when confronting common experiences of bias. Note that these are not meant to be used verbatim, like scripts. They will be more effective if delivered in language that seems like it’s you talking, not me.

Incorrect role assumption.

You, a woman, are negotiating a deal with Wilson, and you have brought along your summer intern, Jack, to take notes. But Wilson directs his comments to Jack.

What you might be thinking: You’re assuming Jack is the boss because he has a dick. Typical.

“I” Statement: Wilson, I am the person you are negotiating with. This is Jack, my summer intern.

Incorrect “task” assumptions.

You get asked to take the notes in every meeting.

What you might be thinking: Because I’m a woman, you assholes always ask me to take notes.

“I” Statement: I can’t contribute substantively to the conversation if I always have to take notes. Can someone else take notes this week?

Ignoring one person’s idea, then celebrating the exact same idea from a different person moments later.

Every time you offer a recommendation you get ignored, but when a man says the same thing five minutes later, it’s a “great idea.”

What you might be thinking: Why are you hailing him as a genius when he is simply repeating what I just said two minutes ago?

“I” Statement: Yes, I STILL think that’s a great idea. (N.B.: You don’t have to do this for yourself; you can ask upstanders on your team to notice when an underrepresented person makes a key point but someone from the majority later repeats it and gets credit for it; ask the upstanders not only to notice but to chime in and say, “Great idea, it sounds a lot like what X said a few minutes ago.”)

Conflating people of the same race or gender when they are the minority in a group.

You are one of two people of your ethnicity and/or gender on your team of thirty people. Multiple people keep confusing the two of you.

What you might be thinking: We don’t all look alike, you asshole.

“I” Statement: I am Alex, not Sam.

Tips for leaders: Bias interrupters.

Leaders cannot pass the buck here — it’s essential to carefully create the conditions where upstanders feel an obligation to call out bias when it happens, people harmed by bias feel they won’t be further punished for pointing it out, and people who demonstrated the bias don’t feel attacked when it gets pointed out. Consider the steps your organization has taken to create an environment where folks can test out new ideas and make mistakes — this is done by design.

To build the foundation atop which folks can feel comfortable standing up when they spot bias, the Just Work team advises creating a shared vocabulary they call bias interrupters. “It could be a phrase or a word that your team or organization uses to identify bias in the moment — like ‘purple flag,’” says Bryant. “So if you’re sitting in a meeting and someone says ‘Hey, I’m throwing a purple flag,’ everyone knows that there was some bias that cropped up.”

But what happens next? “The norm that we recommend is if you're the person that might be being flagged or the person who is exhibiting that biased behavior, say, ‘Hey, thank you for pointing that out. I apologize.’ You note it and then you can correct that moving forward,” says Bryant. “But a lot of times we actually may not understand it. So then the norm should be, "Hey, thank you for pointing that out. I'm not quite sure I'm understanding what you're flagging, but let's talk about it after the meeting and keep going.”

Interrupting bias is not something leaders can simply outsource.

If each meeting grinds to a halt every time someone throws the purple flag, you’re going to slow down the pace of business, which is critical to any startup’s trajectory. If you want people to actually use the shared bias interrupter vocabulary, you’ve got to strike the balance between interrupting bias in the moment, while leaving space to unpack those missteps later.

Tips for leaders: Quantify your bias.

“Pretty much any tech leader will tell you that they’re data-driven and make decisions rooted in the data. Yet leaders are often very reluctant to actually quantify and measure their bias,” says Bryant.

If an employee missed a sales quota or wrote buggy code, management would never accept “Well, I tried” as an excuse. They’d say, “Results matter.”

There’s plenty of areas to get started digging into the data and treat your DEI work just like any other critical number on your bottom line. We’ll summarize just a few that the Just Work team outlined:

- Percentage of resumes reviewed from underrepresented folks.

- What are the backgrounds of the people who made it to the interview process?

- Of the teammates getting promoted on the team, how many are underrepresented?

- Are men and women being paid the same for equal work?

LESSON #4: CONFRONT PREJUDICE WITH “IT” STATEMENTS AND CLEAR STANDARDS FOR CONDUCT.

While prejudice and bias may be used interchangeably, “Just Work” irons out the nuance between the two that often gets lost — biases are unconscious assumptions that we don’t really believe or mean if we stop to think, while prejudices are beliefs we consciously accept. It’s the difference between quickly assuming the only woman in the meeting is someone’s assistant, versus believing women should only be in support roles rather than leadership seats. “Leaders are not the thought police. People can believe whatever they want, but they can't impose their prejudiced beliefs on others,” says Bryant.

Tips for upstanders and people harmed: The “It” Statement.

Before you return to your trusty “I” statement, “Just Work” advises a different approach when confronting prejudice. Here’s why: “The “I” statement invites someone in to understand things the way you understand them. It holds up a mirror. The problem with prejudice is when you hold up a mirror, the person’s going to smile and say, ‘Yeah — I like what I see!’” says Scott.

Instead, tweak the formula slightly, via this excerpt from “Just Work.”

What do you say when people consciously believe that the stereotypes they are spouting off about are true — when you are confronting active prejudice rather than unconscious bias?

People won’t apologize for their prejudiced beliefs just because you point them out; they know what they think. So why bother discussing it? The reason to confront prejudice is to draw a bright line between that person’s right to believe whatever they want and your right not to have that belief imposed upon you.

Using an “It” statement is an effective way to demarcate this boundary. One type of “It” statement appeals to human decency: “It is disrespectful/cruel/et cetera to...” For example, “It is disrespectful to call a grown woman a girl.” Another references the policies or a code of conduct at your company: For example, “It is a violation of our company policy to hang a Confederate flag above your desk. It invokes slavery and will harm our team’s ability to collaborate.” The third invokes the law: For example, “It is illegal to refuse to hire women.”

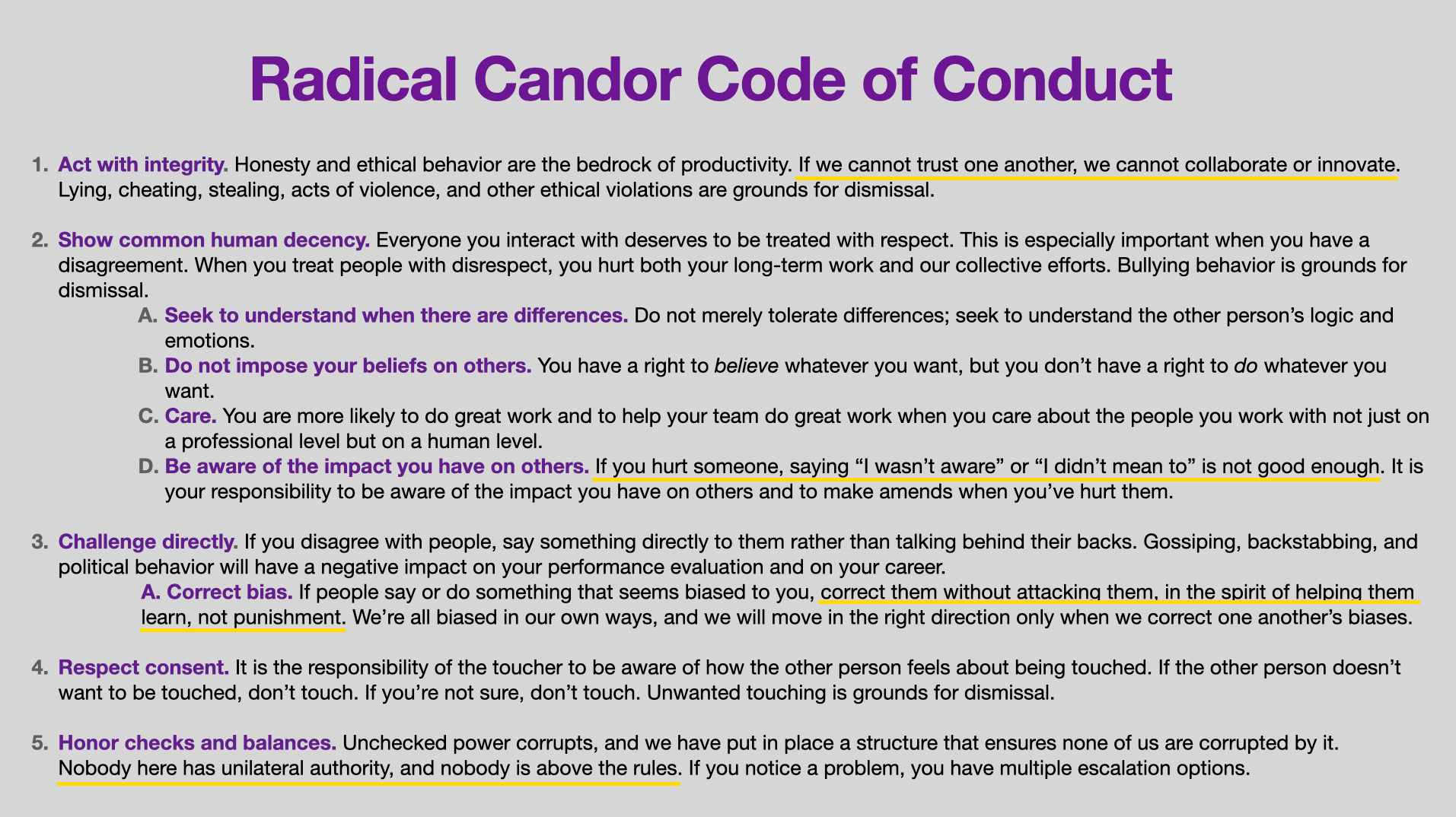

Tips for leaders: Code of Conduct

Maybe you’re a startup leader in the earliest stages of building a company and haven’t felt the need to write a code of conduct for the small team. Or perhaps you have an early version that was drafted long ago, which most folks forgot about after their first day of onboarding. Either way — that’s a mistake.

“Leaders are responsible for setting and communicating clear expectations about the boundaries of acceptable behavior. A code of conduct is one of the best tools for ensuring expectations are clear and fair. A code of conduct does not tell people what to believe but instead what they can and cannot do,” says Scott. “Writing a code of conduct takes time, but it will push you as a leader to think as clearly about behavior as you do about performance. It forces you to articulate what is OK and not OK to say and do in your workplace, and to decide what the consequences ought to be for violating the standards you are setting forth. When do people get a warning, and what are grounds for immediate dismissal?”

Too many leaders act as if creating fair and equitable working environments is somehow separate from their core job.

To help get you started here’s an early draft of Radical Candor’s code of conduct:

LESSON #5: DON’T MAKE EXCEPTIONS FOR THE “BRILLIANT JERK” — CONFRONT BULLYING WITH “YOU” STATEMENTS & CLEAR CONSEQUENCES.

When we hear the word ‘bully,’ most are probably transported back to the schoolyard — not the meeting room. And that was certainly Bryant’s reaction when she first read Scott’s book. “If you would have asked me, ‘Trier, have you ever been bullied in your career?’ I’d say, ‘No way. Have you met me? If you come for me, I’m going to come right back for you,’” she says. “Then you look at the simple definition of bullying as being mean, and we can all probably look at our workplace experiences and think of something that resonates.”

Tips for upstanders and people harmed: “You” statements.

When you’re faced with a workplace bully, whether it’s a nagging issue or a one-off uncomfortable moment, “Just Work” prescribes a “You” statement. Scott first stumbled on the impact of the “You” statement from an unlikely source — her young daughter.

“She came home one day from school upset that a kid was giving her a hard time on the playground. I did what lots of parents do, and advised her to use an ‘I’ statement: ‘When you knock my lunch off the table, I feel sad.’ That got a big eye roll — her teacher had made the same suggestion,” says Scott. “She finally said, ‘Mom, he’s trying to make me sad. If I tell him he hurt my feelings, it’s like saying “Mission accomplished!” Why would I do that?’ She was absolutely correct — and gave me some wisdom I could bring into the workplace.”

Here’s an excerpt from “Just Work” that further unpacks the impact of “You” statements:

One way to push back is to confront the person with a “You” statement, as in “What’s going on for you here?” or “You need to stop talking to me that way.” A “You” statement is a decisive action, and it can be surprisingly effective in changing the dynamic. That’s because the bully is trying to put you in a submissive role, to demand that you answer the questions to shine a scrutinizing spotlight on you. When you reply with a “You” statement, you are now taking a more active role, asking them to answer the questions, shining a scrutinizing spotlight on them.

Tips for leaders: Create three consequences for bullying behavior.

“Plenty of organizations have what people may call ‘the brilliant jerk.’ We know that they’re high impact and critical to the business, so we turn the other way when they mistreat others,” says Bryant. And while their work outputs may be quantifiable — deals closed, commits in GitHub, or marketing pipeline — how that toxicity permeates throughout a team’s DNA is harder to measure but no less critical.

To tackle workplace bullies, companies must commit to doing the work, rather than putting on blinders and hoping the problem works itself out. Here are the three types of consequences outlined by “Just Work.”

- Conversational consequences: As a leader, your first response to bullying should be to pull the bully aside and give clear feedback. Outline what you noticed and how it negatively affects the team. Then explain that if the behavior continues, it will be noted in their performance review and may affect compensation and even their future at your company.

- Compensation consequences: Compensation shows what a leader values. Never, ever give a raise or bonus to people who bully their peers or employees. Atlassian, an Australian enterprise software company, provides a great example of a performance management system that actively punishes bullying. Managers rate employees along three different dimensions: how they demonstrate company values, how they deliver on expectations of their role, and the contribution they make to the team. Employees get a separate rating for each of those areas, not just an average rating.

- Career consequences. Do not promote bullies. It’s that simple. Give them feedback, encouragement, goals. If the behavior does not change, fire them. The long-term damage these people cause is not worth any quarterly result they may be delivering. As many leaders have observed, it’s better to have a hole than an asshole on your team.

WRAPPING UP: STARTUP LEADERS CAN’T COMPLETELY GIVE AWAY THIS LEGO.

Scott wraps us up with a call to action for company-builders: “When you start a company or start a new team, you’re creating and designing the systems that are going to impact the way people in the organization behave,” she says. “You may not like to think about it this way, but if you are not consciously designing for systemic justice, you’re creating systemic injustice at your company.”

And while founders may hold on tightly to the product org or day-to-day sales, often the work of crafting DEI policies and culture that supports all sorts of folks is a lego they’re too quick to give away. That’s a mistake, says Bryant.

Too often we think of DEI and say, “Who are the underrepresented folks in the organization? Here, you all solve this.” And that’s as silly as me saying “I have teeth, I don’t need a dentist.”

“Founders need to acknowledge and respect DEI the same way you do all your other disciplines. You came up with the idea for your company, you hired engineers to build your product, you hired salespeople to sell the product,” says Bryant.

And just like Radical Candor gave folks a framework for considering feedback with a more tactical lens, Scott’s got the same hopes for “Just Work.” “A lot of thought goes into the risks of speaking up. We need to start thinking more about the risks of being silent. We need to change the default from silence to speaking up.”