Kim Scott wanted to stay home in the morning long enough to have breakfast with her young twins. So she did the logical thing — she sent an email to her team asking if they could start their morning meeting an hour later. “I expected people to pat me on the back for being an awesome new mom,” she says. “Instead, I got one of the most painful criticisms ever.”

This was when she was heading up AdSense Online Sales and Operations for Google — a huge global team. Shortly after pressing send, she got a response from a member of the Dublin team to the effect of: Some of us have children too, and now we’re going to be late for dinner. The time change hadn’t occurred to Scott, who had no idea how to respond. “It was incredibly difficult not to react defensively. All I could do was stay silent, count to 6 and apologize.”

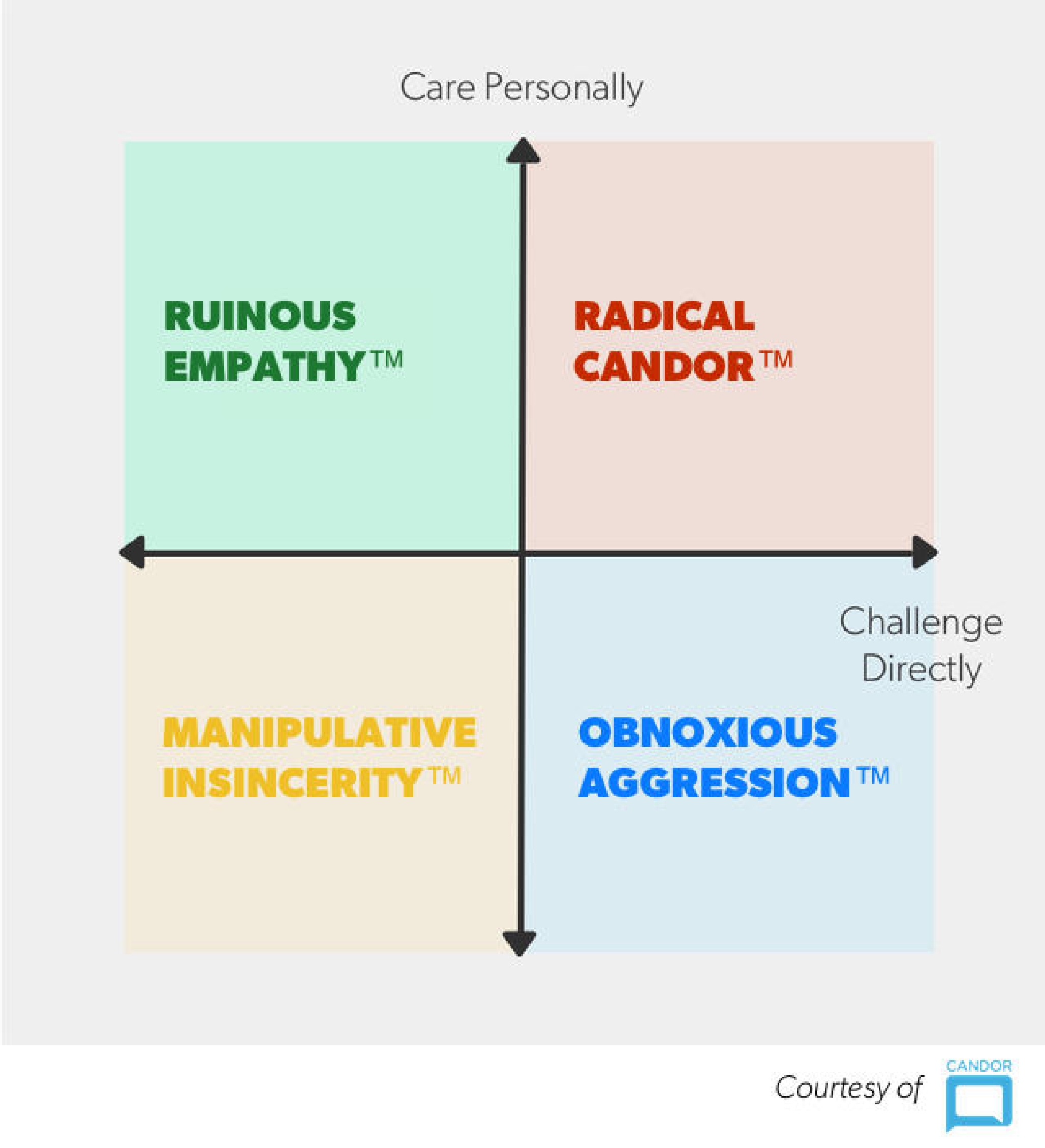

Getting pointed feedback isn’t easy for anyone. And it can be even harder for managers who rarely receive it once they get to a certain level. But being able to not just take, but truly hear and understand Radical Candor — as Scott has now virally defined it and expands on in her new book — is one of the most important skills you can learn in your career.

Today, Scott has teamed up with former fellow Googler Russ Laraway to co-found Candor Inc., a software and content company helping companies of all sizes make authentic, constructive feedback a cornerstone of their cultures. Scott and Laraway have both written and spoken often on how to give Radical Candor to colleagues. In this exclusive article, they turn the tables and focus on how to listen.

As a refresher, here’s Scott talking about Radical Candor at last year’s First Round CEO Summit:

YOU HAVE TO ASK FOR CRITICISM

Especially if you’re a leader, you can’t expect other people to be proactive about giving you feedback. They’re busy. They don’t want to offend. They don’t want to get on your bad side. And even if you’re an individual contributor, you might be starved for guidance. Your manager might be afraid to hurt morale, or has nothing top of mind, or doesn’t prioritize it. It’s up to you to get the information you need.

As a manager, asking for feedback is a powerful opportunity to lead by example that will have ripple effects. By asking repeatedly and consistently for criticism, you seem much more receptive and people are more likely to say things. On top of that, you make everyone in your org more comfortable with receiving and therefore giving criticism because it’s not cast as negative or damaging.

Asking for criticism can manifest itself in different ways — either indirectly or directly. The best tack is to do both.

Asking Indirectly for Feedback

It’s possible to foster an atmosphere where criticism is rebranded as a gift you give or a service you do for someone else, says Scott.

One of the best ways to ask for criticism is to share the criticism you've already received.

For instance, Michelle Peluso and several other CEOs are known to email their own 360 performance reviews to the entire company. This accomplishes two things: It makes it clear they are open to and grateful for feedback, and that there’s no reason to hide even the worst mistakes. And it gives everyone at the company the ability to chime in and have a stake in how the leadership works.

At Google, Scott used to ask her reports who criticized her privately to restate their thoughts in public meetings. Laraway in particular was very good at this, bringing a certain theatricality to the proceedings that really commanded attention.

“There’s this rule we’ve all accepted that you must criticize in private, but when you’re the boss, you’re the exception to the rule,” she says. “You want people to see how you’ll react — that you can take it and will appreciate it.”

You want to make acceptance of your own mistakes as visible as possible to create a culture of healthy feedback, she says. At one point, a member of her team offered her feedback and she responded poorly, holding onto her point of view. When she realized she was indeed wrong, she took a large crystal statue from her office and gave it to the employee, saying, “This is my you-were-right-and-I-was-wrong gift to you.” Whenever anyone asked about the statue — and they always did — they got to hear the story and Scott’s open attitude toward feedback was part of it.

“You have to work really hard and really consistently to get criticism free flowing up and down and sideways through your team,” says Laraway. “As soon as you have one convert who is willing to give you Radical Candor, treat them like gold. Create a network effect that gets you more feedback.”

In his experience, you have to dedicate yourself to getting that first person to finally open up and say something surprisingly candid about you, their manager, in front of the team. You have to go above and beyond to make it acceptable, and even championed. So when it happens, you have to reward the bravery with an incredibly warm response.

Think about how much energy it takes for someone to offer tough criticism to their boss. If you mess up receiving it even one time, that's it. You might not get feedback again for a while.

Eventually, the goal is to parlay this positivity you generate with your responses into helping everyone on your team recognize and freely admit to their own mistakes — after all, socializing self-criticism makes it healthier and more actionable. One of the best ways to do this is to start a light-hearted yet consistent ritual where people are often rewarded for this tough brand of honesty.

“In our old AdSense All Hands meetings, we’d ask people to stand up and talk about a mistake they had made over the last week — and whoever had messed up the worst would get a stuffed animal we named Whoops the Monkey,” says Laraway. “The winner of Whoops would get to choose their successor the following week and so on.”

It sounds like a game, but the group was more than skeptical at first. No one wanted to cop to a mistake, much less give a little spiel about it. “We even told people that if you share at all-hands, you get instant forgiveness — and you have the incentive of helping all of your teammates avoid the same mistake,” says Scott. Still, it was like pulling teeth — until she put a $20 bill on Whoops’ head. “It’s like the money gave people plausible deniability — they could say they were only sharing for the money, but that wasn’t it. It just broke the ice.”

Eventually, the Whoops ceremony caught on. People saw no negative consequences for sharing, only a lot of support and encouragement. Soon, whenever that portion of the meeting came up, there’d be volunteers at the ready. As a result, everyone got to learn from each other’s pitfalls, it made it safe to fail which fostered more innovation, and they got to post-mortem projects with greater honesty and depth. Most importantly, it made it easier for people to criticize their peers — perhaps the most difficult thing to do — because criticism itself had been defanged.

Create a culture where everyone knows criticism is about helping each other do the best work of their careers.

Asking Directly for Feedback

“On one of my past teams, there was a woman who kept getting passed over for promotions. She knew it but didn’t know why,” says Laraway. “The reason hadn’t been given to her but was discussed behind her back.”

This is the kind of behavior that muddies cultures and weakens trust among teams. To make sure this doesn’t happen to you and the people you work with, develop what Laraway calls a “Go To Question.”

Your Go To Question is designed to get at what’s happening in a way that’s easier because it’s non-confrontational, inquisitive, and reframes what people say as a positive.

“Bill Berry at Tacoma Power is known for being a really thoughtful manager, and part of it was he would get people to tell him what they were really thinking,” says Laraway. “He’d do this by saying to them, ‘Give me some advice.’ Then he’d just wait. He’d wait forever. And eventually, he’d hear all kinds of stuff that surprised him and made him and the organization better.”

By re-casting any criticism as advice, he made people feel helpful. And the silence made it clear he was invested in what people had to say. “Another variation I’ve heard from other leaders is, ‘Is there something I could do differently to make it easier to work with me?’”

Your Go To Question could also be in the form of a hypothesis that greases the wheels.

“Let’s say I have a hunch that I’m not doing something well,” says Laraway. “When I state it as a fact to one of my reports, I give them an in. Like I might say, ‘I imagine that you having to constantly chase me down to review those reports is frustrating...’ If it is in fact frustrating, that person has clear runway to say so now. This can be great if you have some more timid people on your team. You’re offering them a straw man, and even language to use to talk about it.”

If you're having trouble getting feedback, start with being self-critical and give someone a chance to agree.

As a leader you have to be constantly vigilant of openings to encourage criticism of your work. A big part of this is reminding yourself over and over again how valuable and necessary this feedback is. Turn a past instance of receiving feedback into a touchstone that keeps this top of mind for you.

For Scott, it’s the time one of her colleagues called her on her penchant to fire off emails without thinking through the consequences. For a while, she’d dash off terse notes for expediency, not realizing they caused massive anxiety for their recipients. Until one day she got a note back: “You’re awfully fast to hit send, Kim.”

“That stung, but he was exactly right,” she says. “I haven’t talked to him in years now, but at least once a week when I’m about to press send, I think of that comment and it saves me from myself. It’s made me more aware of how much I genuinely need those kinds of comments.”

EMBRACE THE DISCOMFORT

Borrowed from Intel CEO Andy Grove, “Embrace the discomfort” is a vital mantra for anyone who wants Radical Candor from their colleagues.

“There’s a false assumption that making people comfortable will make it easier for them to criticize you, but that’s not the case,” says Scott. “When you ask someone who works with you or for you for criticism, just accept that you’ve put them in an extremely uncomfortable position.”

Trying to make it better isn’t doing either of you any favors. So don’t jump in to cut them off, or make it easier in some way. Drive home the fact that you need their thoughts to get better at your job, and don’t let awkwardness get in the way.

“When I taught at Apple University, I would often ask rooms full of people what they thought about me, and I would count to 6 before jumping in to say something else. I’d just let the question hang out there,” says Scott. “You’ll be shocked how long that is. Most people can’t endure the silence. Someone will say something.”

Early on, the Toyota Motor Company took an even more stringent approach. They painted a big red box at the end of every assembly line, and had new employees stand in it. They weren’t allowed to leave the box until they had said something critical about the company’s operations. This was deeply uncomfortable given standard treatment of authority, so extreme measures had to be taken.

Michael Dearing, founder of Harrison Metal, took a softer approach when he led product marketing at eBay. He set an orange box in a high traffic area of the office and told people to drop criticisms and questions and pointed comments into it whenever they thought of something. Then he would pull them out at the all-hands without previewing any of them and answer authentically off the cuff. He had to embrace his own discomfort and respond positively to whatever came up.

Soon people seeing the easy way he accepted candor would just come up and volunteer their thoughts in person. The more the behavior was rewarded, the more people offered up ways to improve.

Laraway observed a similar effect at Twitter during his team’s monthly business reviews. The first time they asked people to surface what wasn’t working well, they only got superficial remarks designed to tiptoe around others’ feelings. It took a few months to get to a point where people dug into what had really happened and why. And they got there through sheer persistence. “We just wouldn’t stop telling people the mission of the meeting was to get to the real critical nitty gritty of what was broken,” he says. “As a team we had to just be uncomfortable together repeatedly and not give up.”

ALWAYS REWARD THE CANDOR

This harkens back to Laraway’s point: You have to treat the first people who freely criticize you like gold. In fact, you have to treat everyone who does like gold, always — but those first couple are important to reward in particular. They’re capable of turning the tide in favor of feedback.

A while ago at Candor, he suggested a product change in a meeting and met zero resistance. A week later, they met again and the change hadn’t been made. When he asked why, one of the engineers finally admitted, “We thought that was a terrible idea.” Yes, he waited before saying it, but he said it.

“I knew this guy loved coffee, so I bought him a Starbucks gift card and wrote on it, ‘That’s a terrible idea,’” says Laraway. “I followed up with an email thanking him for saying what he really thought. Later, he told me he really appreciated the leeway to say things, even if they were impulsive.”

Never ever criticize the criticism. Just say thank you.

“You have to listen with the intent to understand,” says Scott. “Don’t interrupt. Don’t cross-examine.”

One thing that hobbles managers in receiving feedback is a facet of how they give it. Managers, more than anyone, feel burdened to give people examples when they offer criticism. They don’t want to just say, “Hey you’re inarticulate in meetings,” they’re drilled to say, “You could have expressed yourself more clearly last Thursday when you said X.”

This training gets in the way when someone gives them feedback and their knee-jerk response is to ask for specific examples. “It’s really hard when someone tells you you did something wrong to not say, ‘when did that happen?’ or ‘what makes you say that?’” says Scott. “This makes you sound defensive, like you’re disagreeing, like you’re trying to poke holes in their argument. Especially if you outrank the person, you’re basically saying, ‘Where’s the evidence of that?’”

The truth is, it’s very hard to cite exact examples when you’re put on the spot. People are often very good at pinpointing how they feel about a co-workers performance, but have a difficult time explaining or remembering what led them to that conclusion. If you press on this, you’re not rewarding the candor, and you’re robbing yourself of future feedback.

On the contrary, you could say, “Oh I see. So if I did X, Y, and Z differently, that would help you in A, B and C ways, am I right?” You not only demonstrate that you heard and understand them, you’re getting them to agree with you, which kicks off positively-framed dialogue.

Another way Scott has avoided this trap is encouraging her co-workers to give her tough, candid feedback right away — almost instantaneously. For a while, she even wore a rubber band around her wrist that any of her colleagues could snap when she interrupted them. It helped her break the habit.

If you store up all this feedback for one-on-ones or performance reviews, you’re going to fall into asking people for examples they can’t give you. And you’re oddly depriving them of data they could use to get better until an arbitrary date on the calendar. Give everyone permission to offer impromptu feedback to dramatically increase the amount of information being exchanged.

GIVE AS GOOD AS YOU WANT TO GET

Receiving helpful Radical Candor will only happen if you give it too. As a leader, it’s your responsibility to set the tone for this by delivering effective feedback yourself. And usually this boils down to a mindset shift.

“Really ask yourself why you pull your punches when you’re giving feedback. Is your empathy actually productive or are you just trying to spare someone’s feelings?” says Laraway. “You can’t control how other people are going to feel no matter what. All you can do is tell them you’re trying to help them grow, and remind them that human beings learn much more from criticism than praise.”

Give criticism in person as often as possible. Don’t skimp on this. Much of communication is non-verbal. So if you’re just a disembodied voice over the phone telling them they did X and Y wrong, you’re missing most of the interaction. There’s no way for you to really understand how they’re receiving what you’re saying, if they’re hurt or confused. You have no way to gauge whether you should dial your comments up or down.

The clarity of your feedback is measured at the other person's ear, not your mouth.

“People focus so much on how they’re saying something, that they spend 0 time considering what the other person is actually hearing them say,” says Scott. “When someone is engaged, they lean in. When they’re shutting down, they cross their arms and distance themselves — I feel like we’re very attuned to these basic signals in our personal lives but then fail to bring that to work with us. If you have all this data about how you’re being heard, you can be nimble, rephrase, consider sharing something else.” In short, don’t fly blind if you can help it.

Lastly on this point, don’t let praise be the area where you ruin your credibility. Both Scott and Laraway have seen this happen too many times. A manager wants to heap on the positive reinforcement, but there’s so many ways that can go wrong.

“If you’re a boss and you say one thing that sounds sort of off or indicates that you don’t know what’s truly going on — you lose more than you stood to gain in the first place,” says Laraway. “Like if I complimented my content manager on a blog instead of a video. Or on the email campaign she sent Thursday when it was really out on Tuesday. You erode confidence in yourself.”

The further from the front line work you are, the more careful you have to be about details in both praise and criticism. People trusting that you’re familiar with their work and that you know what you’re talking about is everything. A quick fix is to not just praise what was done, but to go the extra mile to tell the person and the team exactly what impact the work will have.

RELY ON RITUALS

“So many people today talk about building ‘learning cultures’ where people can openly talk about their errors and ways to improve,” says Laraway. “Without actual, everyday blocking-and-tackling tactics in place, nothing will change. You have to establish triggers and rituals for yourself and your team to bring feedback to the surface.”

Small rituals split the difference between nothing and elaborate systems and process. The key is to make these rituals lightweight enough that they don’t take up any significant time, make sure they recur regularly, and make them gimmicky (or quirky, or memorable, whatever you prefer). Whoops the Monkey is a prime example. The more goofy or odd you make these triggers, the more abstracted feedback will be from negative feelings — and the harder they will be to forget to do.

“Don’t create more process. Create rituals that fit seamlessly into what you already do every day,” says Scott. “Having people pass around a stuffed animal at the end of a meeting once a week didn’t take time out of our days. But even now when I think about that monkey, I remember how important it is to ask for feedback, react well to it, and be present and conscious of opportunities to use it.”

Photographs courtesy of Candor, Inc. and art courtesy of Vanessa Brantley Newton and thanks to Rachel Awes.