It seems that, simultaneously, there are many rules and very few rules about employee compensation. Benchmarks, structures, things you can and can’t ask — most of which early-stage founders are left to navigate themselves, coming up with a package for their first hires they feel makes the most sense.

The goal is simple: Bring on the best talent you possibly can. Getting there is far more opaque.

How should you structure the equity and cash in your offer? Should different roles get different comp strategies? Do you need a comp strategy at all, as such an early stage company? These are all questions that founders ask themselves before sliding an offer sheet across the table.

At The Review, we believe the best lessons come from those who have done it themselves — and lived to share the learnings. So we’ve compiled valuable insights from industry leaders who’ve built and scaled compensation strategies at some of the world’s top companies. We’ve broken their advice down into the supposed “rules” you can feel free to ignore, and the ones that actually do make sense to follow.

Our expert roster includes:

- Kaitlyn Knopp, Pequity (formerly Instacart and Google)

- Varun Anand, Clay

- Qasar Younis, Applied Intuition

- Colleen McCreary, Confluent (formerly Credit Karma)

- Tyler Hogge, Pelion (formerly Divvy and Wealthfront)

- Stephanie Berner, Smartsheet (formerly Atlassian)

- Udi Nir (formerly Instacart and eBay)

- Molly Graham, Glue Club (former Facebook and Quip)

Rules to break

When it comes to comp, there’s a lot of advice to sift through — and not all of it is suitable for early stage. What works for a company with hundreds or even thousands of employees won’t translate to a team of ten. Here's some common wisdom as an early stage founder you can consider ignoring.

Over-giving equity to land top candidates

It’s one of the oldest startup compensation strategies: promote your company’s upside and use equity to woo the best talent. In negotiations, candidates will expect it as part of any package, and will usually expect it to be higher the earlier the company is — especially if you’re trying to convince them to leave the stability of their current role and take a bet on you and your company. But according to Kaitlyn Knopp, who has built compensation programs at companies including Instacart, Cruise, and Google, and is now the co-founder of HR automation platform Pequity, founders shouldn’t assume they have to sell the farm.

“I see a lot of early founders who, because they're desperate for talent, come to the negotiation table and lay out a ton of equity — because oftentimes they can't afford a lot of cash,” Knopp says. “But a good thing to remember is that this phase will be short-lived. Yes, you do need that talent, but you are offering a lot just by giving someone any equity in the company.”

Knopp suggests, as a rule of thumb, that your first ten hires shouldn’t exceed 10% of the total equity pool. Though even that, she notes, can be aggressive. “That’s assuming you’re giving 1% to each person. To give perspective, a very late growth stage company might give 1% to their newly hired CEO. So that is a lot of equity to offer to someone early.”

Knopp cautions against assuming those early shares will dilute over time that they’ll hardly matter. “Those decisions come back to haunt you. I've had to work with different organizations that have fully distributed their entire equity stock option pool at a very small employee count. They have to pull equity off investors and founders. It's not a fun process to go through.”

Her advice: Outline your comp philosophy (more on that below) and stick to it. “You have more leverage than you think you do.”

Educating candidates on equity can help them understand its value, both now and in two, five or ten years. That’s according to Molly Graham, who helped structure comp at Facebook and Quip.

“No matter how smart the people who walk in the door, many won’t understand how to value their equity,” she says. “At Facebook we put together a guide to understanding your equity when we made offers. It was simple to do and made people feel more comfortable with the offers we were making.”

Paying at the top of the market (just because you can)

While it's more common for early-stage founders to over-index on the equity side of things, cash compensation has also increased in an attempt to land talent. Qasar Younis, co-founder and CEO of Applied Intuition, says he’s seen new hires receive eye-watering starter salaries that become, as a company grows, “not sustainable.”

“Historically, the right way to incentivize in startups was low cash, high equity, and get rich through the growth of the stock,” he says. “Because of large fundraises, which really come from lots of funds existing — which has a downstream impact — founders have a lot more cash on hand. They overpay.”

Younis believes this can lead to compensation strategies that simply don’t make economic sense. “You can look at Levels.fyi — you often get paid more to go to a startup than to Google or Facebook, and those companies generate billions in cash flow every month,” he says.

Discipline around salaries for early hires isn’t about austerity, Younis argues, but integrity. When founders raise massive rounds and, in turn, inflate compensation, they sever the link between value creation and reward.

“The incentives are not there to build a functioning business. That's the reality,” he says. “We’ve tried to keep that focus: make this a viable company. Being cost-conscious is one of our core values. And it’s worked out.”

Younis’s approach at Applied Intuition has been to manage the balance between stewardship and reward. It's about establishing the right early comp so that you have room to reward results. And hopefully the equity is what ends up catapulting total comp. “The vast majority of our employees are now at the 99th percentile of compensation, but they’re not there because of their first offer,” he says. “They’re there because the stock price grew. That’s the right way to do it. You get stock while it’s cheap, you contribute to the company’s success, and you get rich over time.”

Waiting for review season to talk about pay

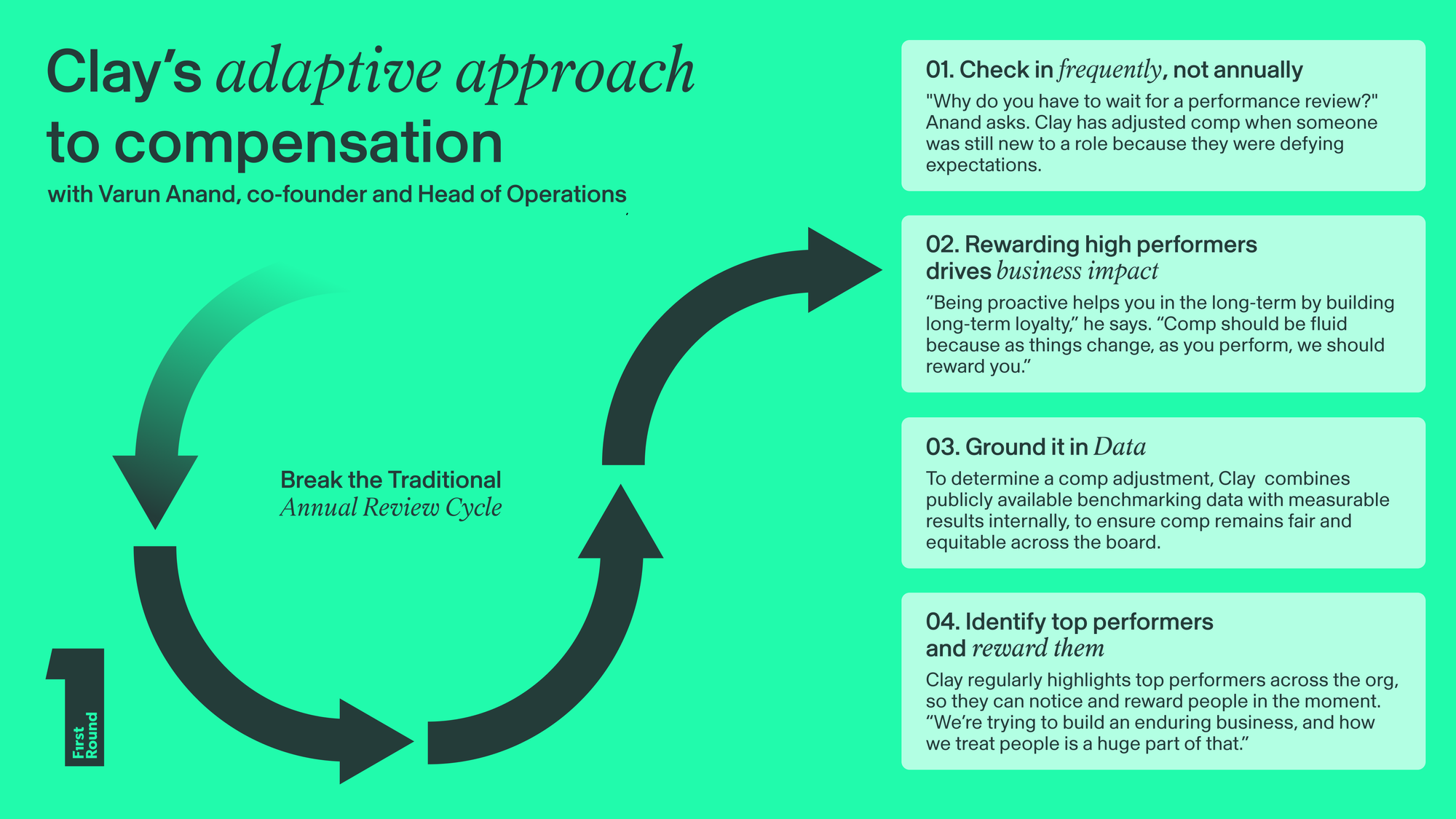

Clay co-founder Varun Anand believes updating comp at review cycles is arbitrary. "Why do you have to wait for a performance review?" he asks. "It benefits the company to save some money on the time that person is higher performing than what you're paying them."

But at Clay, they've taken a far more fluid approach — recognizing impact in real time and rewarding that with off-cycle comp increases.

“We are very proactive in giving people more compensation if they are truly high performers,” Anand says. “Sometimes people have just been here for a few months when we adjust comp. It’s because we noticed they’re defying the expectations we had when they joined. We’re not trying to wait for some formal performance review to make that happen. We do it immediately.”

Anand’s philosophy on separating performance reviews and compensation is informed by his own past experiences as a frustrated employee. “I’ve been at companies where I felt like a top performer, felt I was warranted more compensation, but the process of getting it was painful. You ask for it, they tell you to wait for the performance review and it leads to embitterment.”

Anand believes it’s the wrong strategy for getting the best out of your people. “Being proactive helps you in the long-term by building a really strong relationship with this person, and long-term loyalty,” he says. “Feedback is a gift to you to help you improve. Compensation is fluid because as things change, as you perform, we should reward you and you should get more.”

To ensure comp remains fair and equitable across the board, at Clay they ground every adjustment in data, combining benchmarking data with measurable results showing how a top performer has exceeded expectations. Another approach is to establish a program for founder grants, where on a regular basis stock is awarded to top performers.

“We don't have a formal structured program like that,” Anand says, “but I think that in every case we can justify comp decisions, because we’re rewarding those who are exceeding the expectations of where they were before, warranting more.”

At Clay, they also conduct a general overview of who the top performers are across the org regularly, so they can notice and reward people in the moment.

We’ve built a company that is people-oriented, so they’ll stick with us for the long term. We’re trying to build an enduring business, and how we treat people is a huge part of that.

Treating big tech as the blueprint

The comp structure you design needs to reflect the stage, scale, and constraints of your startup — which means you won’t be able to simply replicate what someone else is doing.

“Most places don't publish their comp formulas or rationale because it is so bespoke,” says Knopp. “I could decide to only ever pay people $100K in cash and everything else in equity. That could be a valid comp program, and it would show up in salary surveys. But that doesn’t mean you should be doing that.”

Adopting Google or Facebook’s pay formulas, equity bands, or bonus schemes without context means you’ll risk over-engineering a system that doesn’t fit your stage, misallocating equity or cash, and creating inequities you’ll later have to unwind. When it comes to comp, you need to build something customized and organic to your company, which means digging into research.

“Read as many resources as possible,” Knopp advises. “Read up on psychology, in particular psychology and reward behavior and how you can incentivize people. Having your own framework is far more powerful than seeing that Google does, for example, total direct comp minus this percentile of salary, plus this bonus cash, then blindly copy-pasting that formula onto your org.”

Rules to follow

Strip away the above-mentioned generalizations myths and what’s left are the rules that hold up under pressure. These practical principles will help you to make compensation fair, defensible, and scalable from day one.

Define your comp philosophy early

While it might feel like you don't need a comp philosophy at 10 or 15 employees, Knopp believes it saves headache very shortly down the line. "Companies suddenly find themselves navigating a maze of tough, emotional conversations that could've been avoided."

Here are a few questions to ask yourself when determining your own philosophy:

- What are the company values, and how can these be reflected in comp?

- What will be the balance of equity versus cash?

- Where will we sit on the transparency spectrum?

- What percentile will we aim for our employees to hit?

- How will top performers be rewarded?

- Is the philosophy fair, simple, and defensible?

- Is it scalable?

Introducing salary tiers, too, will make for a smoother ride as you grow.

People want to get promoted and move up way quicker than you're usually ready for.

“A framework gives you wiggle room. You can say, ‘Okay, we will move you from the first level to the second. Here's some comp attached to it.’ It's consistent, defensible, and explainable.”

What does it look like in practice? You’ll need to define three to four levels that reflect experience and scope of contribution, aligned with company values. Knopp suggests the following:

- Level 1: Junior / entry-level. 0-3 years experience. Early in their career/new to the function. Requires more guidance and mentorship.

- Level 2: Mid-level / experienced individual contributor. 4-7 years experience. Solid practitioner who can execute independently. Doesn’t require constant direction.

- Level 3: Senior / expert. 8-12 years experience. Seasoned professional who brings strategic depth and can mentor others. May begin to define processes or best practices for their function.

- Level 4: Principal / leadership. 10-15+ years experience. Deep expert or early functional leader, may be one of the first managers in the org. Owns a discipline or domain outright. May receive performance-based equity or leadership bonuses.

Once you have defined tiers, use market data to cross-check your salaries are right-sized (resources like Radford and Mercer’s make it easy to benchmark roles). Decide whether you’ll target the 50th percentile of the market — the market median — or a different point on the spectrum that fits your philosophy.

Deciding exactly where you sit can be difficult. Udi Nir is an engineering alum of eBay and Instacart, and while at Instacart, he co-led a taskforce into compensation strategy.

Put yourself in a strong position to win a candidate, but don’t expect to have the best offer every time. The highest comp doesn’t always win. We’ve seen that paying fairly, crafting an exciting role and conveying a compelling mission seals the deal.

A clearly defined comp philosophy might take some work now, but your future self, who’ll need to be able to justify the comp packages of more and more employees, will thank you. Knopp is sure of it.

“It helps you frame the conversation for why one person gets more equity than another, for example. You can defend a lot of these decisions, especially as you continue to grow.”

Try out candidates on a contract-to-hire

There’s a myth that the best talent won’t consider contract-to-hire — but Knopp is quick to dismiss it. In fact, she says there’s no better way to assess long-term compatibility between candidate and company.

Pre-pandemic, people assumed the best talent wouldn’t consider contract work, but that’s no longer true. We’ve had senior engineers and designers take on 10-hour-a-week contracts — and deliver 10x value.

With a contract and NDA in place, Knopp says contract-to-hire is a powerful way to find the right people with the skills and experience you need to drive growth in the near-term while assessing long-term fit.

“You can test each other out for X number of days or months. Then at the end of it, you can talk about if this should be a full-time relationship,” Knopp says, adding the benefits are two-fold.

“One, you get help immediately when you're a small startup. Two, it gives the potential full-time employee a chance to build relationships, and to picture for themselves the value. Explaining your philosophy, mission, vision, values, is not the same as being in the day-to-day with the team, seeing the interactions, seeing how customers are reacting, seeing the problems that you face.”

Such an arrangement also has practical benefits, especially for startups constrained by cash.

“All of our first hires, who are now full-time employees, began as contractors,” Knopp says. “We bootstrapped the first year, so we could not afford to pay engineers full salaries. So we issued equity and made them contractors. It worked out.”

Knopp also dismisses the idea that just because someone is on contract means they’re not fully invested in the product, the company, or the vision.

“I know there's the question, ‘Are they fully committed? Will they give you their all?’ We haven't run into the issue,” she says. “I've seen it be a valid option for senior people who are already at companies who just want to do 10 hours a week. And you can still get a lot of value from the 10X-er working 10 hours a week for you.”

Be transparent and educate (or otherwise be prepared to answer questions constantly)

It’s up to you how you’ll approach comp transparency at your startup. But Colleen McCreary, Chief People Officer at Confluent, and formerly Credit Karma, says opacity comes with a cost.

When she started at Credit Karma, she was tasked with overhauling the company’s approach to comp. “No one understood how they were paid, how additional equity grants were made, or how they were going to get promoted,” McCreary says. “It was this black box — somebody makes a decision, then money just shows up in your account, and you’re left to decide whether you want to stay.”

McCreary worked to remove the shroud of mystery that hung over compensation. “I got up at an all-hands meeting and walked through every piece of it,” she says. “How we pay, what Radford is, what percentile we target, which companies are in our comp set, how often we review — everything.”

McCreary also built a communication loop that reinforced clarity at every touchpoint on the employee journey: orientation sessions for new hires, a Slack channel dedicated entirely to compensation and equity questions, and internal resource pages that made information easy to find. This approach is not only beneficial for employees, who are more empowered on the topic, but for founders and other leaders, who can spend their time and resources on other things instead of haggling over salaries.

If you don't consistently provide clarity and context, all you're going to end up doing is talking about compensation all of the time.

Graham agrees.

“Ask anyone who has managed a team of over 10 people — everyone finds out eventually, and the problem is that feelings about compensation are relative, not absolute,” she says. “You might be living really well. You might be in the wealthiest 1%, but if there’s someone sitting next to you who makes twice as much, you’re going to feel insulted. It’s just a fact. So take that into account when you’re creating your plan. You need to be able to explain (and defend) everything through a logical set of guidelines.”

Calibrate according to function (one size does not fit all)

What motivates someone in sales to excel won’t necessarily move a product manager — or a customer success leader, or an engineer. You’ll want to consider how different roles are incentivized based on their goals when laying out your comp strategy. Let’s take a look at some examples.

For sales, there’s a formula that Graham recommends. “We implemented this sales compensation plan that Jason Lemkin shared for setting initial sales compensation numbers.” To break it down:

- Set a competitive base, but make it pays for itself. Offer sales hires a strong base salary, with the expectation that they’ll generate enough revenue to cover their own costs (including salary and benefits) before earning any commissions or bonuses.

- Double the incentive once targets are met. If most of your reps (approximately 80% or more) are consistently hitting their goals, you can afford to offer a more generous commission — around 20-22%, compared to the standard 10-11%.

- Reward cash-in-hand deals more heavily. To keep cash flow top of mind for reps, pay higher commissions on deals that deliver cash upfront and slightly less for those that don’t. This nudges them to prioritize bringing in cash faster while still driving revenue.

- Pay commissions only when cash is received, not at contract signature: While reps might grumble about it, they’ll respect the logic. It reinforces discipline across the team.

If sales compensation is about driving the motivation to close deals, then customer success comp is about turning that deal into a happy, long-term customer. Stephanie Berner, Atlassian's former SVP of Customer Success, and now Chief Customer Officer at Smartsheet says most CS teams operate best on a base-plus-bonus model rather than pure commission. The key is ensuring incentives mirror the team’s true responsibilities — and evolve with scale.

“I’ve seen the most impact with bonus structures that include commercial KPIs like renewal percentage, expansion, or adoption metrics,” she says. “I’m a fan of that approach instead of explicit renewals quotas, unless you have a dedicated renewals team.”

In short, comp should clarify what the company expects from customer success. Are CSMs accountable for closing renewal transactions? Or for ensuring product adoption and long-term customer health? The outcomes to which you tie KPIs and comp are where your team is going to put the majority of their focus, so choose wisely.

“The thing companies get tripped up by is when you put a significant amount of comp against renewals or expansion quota,” Berner says. “If you want your teams focused on only getting renewals across the line, that is where they’ll focus. Instead, if it’s important that your CS team is paying attention to product adoption, use cases, or integration with other workflows in their business, then you need to incentivize that behavior.”

Product teams, by contrast, have historically existed outside the world of variable comp. But former Divvy and Wealthfront product lead Tyler Hogge, now a partner at Pelion, challenges that orthodoxy, introducing a model that borrows (selectively) from the sales playbook to drive greater alignment across revenue and product.

“It starts with identifying a business outcome for each product a PM is working on, and articulating the metric most closely aligned to that outcome,” he explains. “You then build an incentive structure that rewards PMs for hitting it. My two cents is that while a cash component could work, it should lean heavily towards equity. Great PMs are builders— builders want a chance to have equity in what they build.”

By tying incentives to measurable business outcomes (for example, if ARR increases following feature adoption, or there’s an improvement in retention following a product release) Divvy pushed its PMs to operate with more urgency and clarity.

“Absent incentives, I’ve found that PMs often don’t move with enough urgency or engage in the often awkward conversations about scoping that need to happen with key stakeholders, ”says Hogge. “Focusing on outcomes with aligned incentives keeps the scope from getting bloated, so they don’t make long-term investments on projects and features that are nice-to-haves, but don’t ultimately tie back to a larger goal in a meaningful way.”

Compensation should reinforce the specific value a function contributes to the wider org. Consider the deeper motivations of employees according to their specific role and team.

- Sales thrives on immediacy and ownership, so comp should fuel performance and discipline in equal measure.

- Customer success depends on relationships and retention, so comp should reward long-term value, not short-term wins.

- Product lives at the intersection of vision and execution, so comp should spark urgency and shared accountability for outcomes.