Founders are unrelenting optimists. It’s practically a requisite trait to start a company — you have to suspend disbelief to build toward the future state you’ve imagined.

But if grit goes untempered by realism, blind spots can emerge. When you’ve put everything on the line to make your startup work, it’s easy for happy ears syndrome to set in, only taking in what you want to hear and subconsciously filtering out the rest.

Three-time founder Bob Moore ran into this pitfall while building his first two startups, which, by his own account, netted good-not-great outcomes. In a postmortem, he could easily point to bad timing, market dynamics or fearsome competitors — in other words, things outside of his control. Instead, he calls out the limits of his own judgment as a young founder.

Moore launched his first company, an analytics platform called RJMetrics, on the heels of the 2008 downturn. He and his co-founder muscled their way through a turbulent first few years, successfully bootstrapping the company and finding product-market fit.

Then, the market moved, and they got left behind. RJMetrics still scored a modest acquisition in 2016, but competitor Looker far upstaged them with a $2.6 billion sale to Google. Moore’s second startup, Stitch, was a spinoff of RJMetrics’ data infrastructure tech and nabbed a heftier acquisition in less than two years — but it still wasn't the IPO-scale smash hit that he’d been hoping for.

“If I had to distill the lesson down to something that I wish I had more of back then — and something I’ve worked on relentlessly since — is this idea of intellectual honesty. It’s something that all founders need to care really deeply about,” says Moore. For founders, intellectual honesty can be defined as an openness to — and active pursuit of — the truth, even when it proves you wrong.

For founders, being intellectually honest means being willing to understand the difference between noise and signal in the things that aren’t working in your business.

In this exclusive interview, Moore follows up on his treatise on startup resiliency with a founder’s guide to intellectual honesty, making this abstract concept actionable by laying out a set of tactics to get to the ground truth more quickly. He puts his strategies into context alongside his own experiences as a multi-time founder, offering up specific examples of the biases most beguiling to founders, and sharing how he’s combating them now as he tackles his third company, Crossbeam (a partnerships ecosystem platform he calls the “LinkedIn for data”).

Moore starts by outlining several checks for the early days of company building. He then unpacks how to interpret product-market fit signals, from the warning signs he missed that RJMetrics was losing traction to the indicator he identified for Crossbeam. He wraps up with his takeaways from a growth-stage test of his intellectual honesty: deciding to merge with a competitor.

Moore has had a decade-plus in the trenches to develop these psychological guardrails, which he’s now generously turned into the candid guide he wished he had when he was just starting out.

FIND A CO-FOUNDER WHO BALANCES YOUR THINKING

For many founders, one of the first and most consequential decisions that can predate the startup idea itself is choosing someone to build with. When thinking through your dream co-founder criteria, Moore unsurprisingly recommends adding intellectual accountability to your list.

This is one early call Moore thinks he got right when choosing a co-founder in Jake Stein, who gave Moore some of his most memorable lessons in intellectual honesty when they were building RJMetrics and Stitch together.

He shares an example of how the duo balanced each other out. “Back in the early days of RJMetrics, I’d read whatever the hot startup book of the day was, and I went to Jake with all these ideas from the book and told him, ‘We should do this and this.’ And he said, ‘That’s cool. But what in that book did you not agree with?’” says Moore.

“That took me aback. I hadn’t pushed myself to exist in a space where I could hold two thoughts at the same time — in this case, that this book might have both extremely good ideas and also bad advice that won’t work for us,” he says.

Across a decade and two startups, this dynamic helped both Moore and Stein get good at looking at both sides of a problem.

Being able to hold two thoughts at the same is a core ingredient of intellectual honesty — and helps you not just turn out as a blind optimist who says yes to every idea.

“Jake would sometimes call himself the Charlie Munger to my Warren Buffett. That's how it started out. But over the course of the decade, we converged into both being able to hold those two conflicting thoughts at once.”

“The thing that my co-founder Jake brought to my thinking was helping me become not more pessimistic or critical, but capable of holding two conflicting thoughts in my head at the same time,” he says.

GET HONEST ABOUT FOUNDER-MARKET FIT

In the six-month interim after selling Stitch, Moore attempted to take some time off and get some R&R. Except he couldn’t quit thinking about what he wanted to do next — so he dug up a running list of startup ideas he had tucked away in Evernote (“which would probably be in Notion now,” Moore notes).

“I probably should have gone to therapy, but instead I cracked that list open. I tried to sit on a beach for a couple of weeks and just lost my mind,” he jokes.

This third time around, Moore wanted to build something even bigger than his previous two startups. So he knew he’d have to take some time to mull over which idea had the most legs.

First, he had to whittle down his list of roughly 100 miscellaneous entries — which ran the gamut from B2B SaaS tools to an escape room franchise.

The bias: Over-indexing on fascination with the problem

There’s a common startup refrain that encourages aspiring founders to “fall in love with the problem.” This isn’t bad advice, considering most founders will dedicate years of their life to solving it. But it misses another equally important dimension. Too often, founders — especially those earlier in their careers — fail to take their own strengths into account when choosing an idea, merely chasing market trends or their own passions.

When Moore started RJMetrics, he and Stein were fresh off a two-year stint in venture capital, hungry for a startup of their own. But when they quit their investor day jobs to get RJMetrics off the ground, they didn’t have a strategic game plan beyond wanting in on the heating-up analytics market.

“We went in as mercenaries. We wanted in on this startup game and big data was increasingly a thing. I knew how to write a damn good SQL query. But that was all we had,” says Moore.

Looking back on it now, Moore thinks one of the contributing factors to RJMetrics’ shorter shelf-life was that the founding duo lacked a sense of where the market was headed. “When we started RJMetrics, I didn't have strong conviction. It may have been something that lit up my brain, but I didn’t even know the word ‘dashboard’ until after I started the company. We didn't know business intelligence as a market — we didn't even know who Gartner was,” he says.

Years into building RJMetrics, this absence of a long-term vision became glaring in the product strategy. “We went out in that market and we hustled for the first couple years. But when we got stuck on a product direction, more often than not, we’d turn to the data and customer feedback and say, ‘Well, eight people asked for that, and six people asked for that. So we’ll just build the thing more people want,” he says. “Because we weren’t steering with a solid strategy, we pursued all these product micro-optimizations and landed ourselves in a place where we created a company that creates some value for some people. Our growth was stuck on a local maximum.”

“RJMetrics became designed by committee. We didn’t have a core conviction that a certain specific thing ought to exist because that’s where the market was going. That wasn’t there,” says Moore.

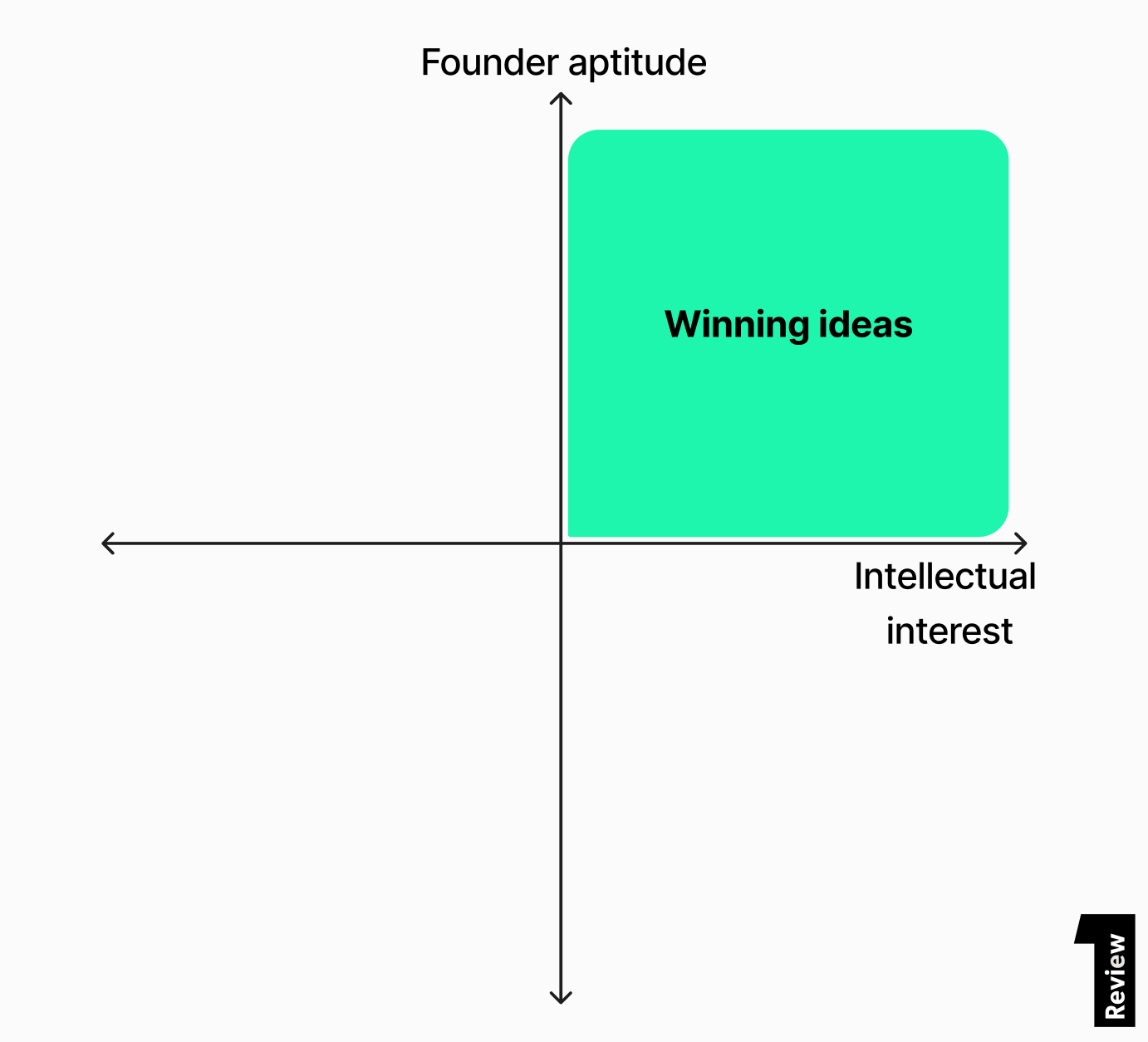

The solve: Map ideas on a two-by-two matrix of interest and ability

So when Moore was assessing ideas for his third startup, he knew he needed to be honest with himself about not only what he was excited to build, but what he was uniquely positioned to build well, given his chops as a multi-time SaaS founder.

To do that, he devised a simple founder-market fit pre-screen — a mental matrix with two dimensions. He posed these questions to himself:

- Intellectual interest in the problem. How much fun would I have doing this? How much would it light up my brain?

- Founder aptitude. What is it about my specific experience that makes me predisposed to being good at solving this problem?

This helped Moore quickly rule out the oddball ideas and pipe dreams. “This exercise took my list of 100 down to 10 or 15 ideas,” he says.

“I had varying levels of where the ideas for my previous companies fell in the two-by-two matrix. I think that was part of why those businesses were base hits, and neither one of them got to an IPO scale,” says Moore.

SEEK FEEDBACK FROM FOUNDERS TO SURFACE HIGH-ALTITUDE IDEAS

With the remaining handful of ideas that landed in the top right quadrant of his mental matrix, Moore wanted to get some outside opinions. But he chose to do things differently for the validation step: He bypassed the classic customer-driven discovery model and instead ran his remaining ideas past fellow founders.

Moore felt that founders could offer more nuanced perspectives — and widen any preconceived notions he might have had about each of these ideas. “Founders are special. They need to develop an extremely high level of empathy and understanding for the needs of people across multiple personas, and also understand a baseline grasp on how markets evolve over time and what makes for something that's more durable and versatile,” he says.

With founders, I wasn’t asking, ‘Would you buy this?’ But instead, ‘Would you start this company? And what are the things that you think you might bump into?’

“Rather than narrowing these ideas down into the scope of how a persona would use it, I was able to broaden my horizons of what they could become,” says Moore. “I wasn't interested in having my next thing be anything other than an IPO-scale business — I wasn’t optimizing for a ‘build it for a few years and sell’ situation. I thought I had one more startup in me and I wanted to see how far I could take it.”

The bias: The illusion of the founder Midas touch

But Moore was aware that with this method of idea validation, he ran the risk of confronting a bias. Founders, a famously optimistic bunch, default to seeing the potential in an idea — and in a fellow founder. So Moore knew a founder friend might still be willing to make a bet on him, even if they thought his idea was bad — and not offer up any constructive feedback.

Moore admits he probably wouldn’t be fully honest if he were in the other founder’s shoes. “If a friend of mine who started and sold a company comes to me with a new idea, I figure they're already attached to this idea and I'm not going to talk them out of it,” he says. “Even if I don't love the idea, if I know this person well enough I actually might still write an angel check and make a bet on them — not because I think the idea is going to work, but because I think this person is not going to allow themselves to fail,” he says.

“So the FOMO of not being in on their next thing is greater than my willingness to create confrontation with them, which isn’t a hard ratio to keep. I'm not going to give them as candid feedback as I should,” says Moore.

The solve: The forcing function of choice

When pitching his ideas to fellow founders, Moore built in a guard to fend off empty flattery: He told each founder to choose which of the three ideas they liked the best.

“I started the meeting by not biasing them in any way. I’d say, ‘Hey, I've got three business ideas. I like them all equally. I want to pitch you on them and see where it goes.’ I did around 20 or 30 of these calls and I distributed the 10 ideas across all of them,” says Moore.

This approach gave Moore much more revealing responses than, “I like that!” or, “That’s cool.” “I made these founders compare and contrast and ask, ‘Why this one? Why not that one?’ This created a forcing function to encourage them to criticize my ideas,” he explains.

The idea for what would become Crossbeam quickly bubbled to the top. Moore knew it was a winner when founders started recommending who else he should talk to — essentially pointing him toward potential customers. The idea had a built-in viral loop.

“With the Crossbeam idea, there was always a next step. People kept telling me, ‘You know who you should talk to about this? Because I know they’ve run into this problem.’ Or, ‘Can you put me on your mailing list so I get updates when you actually start building this thing?’ Coming out of the conversations where I talked about Crossbeam, I was actually cultivating a waitlist, some pent-up demand.”

Product-market fit punches you in the face when you find it.

DISCERN TRUE PRODUCT-MARKET FIT SIGNALS (AND THE WARNING SIGNS OF STAGNATION)

Moore knows all too well that the levels of product-market fit aren’t a one-way door.

RJMetrics arrived early to the data market during a recession and started out with a slow drip of revenue. It later clicked into place and enjoyed a few years of up-and-to-the-right numbers. Then, big players like Amazon Redshift, Tableau and Looker shook up the data stack, and RJMetrics didn’t adjust the product — and lost its momentum.

So he’s developed a clear eye for what’s a mirage and what’s real when it comes to assessing product-market fit. Here, Moore breaks down the corners he refused to see around at RJMetrics and the litmus test he used for Crossbeam.

The bias: A “they’re the dumb ones” mentality

In hindsight, Moore recalls two omens that RJMetrics’ product-market fit was slipping away: a high churn rate, and new competition cropping up.

But he didn’t identify these cues as warning signs at the time. He attributes his failure to recognize what was happening to a line of thinking that’s especially tempting to bullish founders: “We know better than they do.”

Rationalizing worsening churn

Building RJMetrics in a volatile financial landscape meant that there was always some degree of instability with its customers. “We always had a problem with churn at RJMetrics. We had a fairly low entry-level price point, and there were a lot of companies going out of business and getting acquired. We used to call it ‘structural churn’ — a baseline 10% of all our business in any given year would just go away because the companies would go out of business,” says Moore.

But once the modern data stack era rolled around by 2015, the churn was magnified. “All these things started to break at once, and one of them was that churn got a little bit worse. Another was that our outbound SDR program, which used to be super ROI positive, completely stopped working. The economics of it went upside down,” says Moore.

At the time, he and the team brushed off the issue — chalking it up to their customers making bad decisions. “We had a bunch of customers that churned because they decided to go to Looker or because their engineering team was going to take over the analytics stack and the marketing team was losing control of that budget. Our consistent reaction to that was, ‘Oh, they’ll be back in a year,’” he says.

“For the sake of pattern recognition, this happened enough times that at some point, it clicked and we realized, ‘Oh, wait, I think we're the dumb ones.’ This was a pattern that we should have picked up on earlier.”

We tried too hard to contort the data into a narrative that made us sleep better at night.

Writing off growing competition

In retrospect, another clue that the data market was quickly moving away from RJMetrics’ product came from a TechCrunch reporter — but at the time, Moore dismissed the threat that growing competition posed, citing the reporter’s lack of knowledge about the market.

“When we announced our Series B round, Amazon had just launched Redshift as a data warehouse product. It didn’t even register as something that was competitive. It was an infrastructure product selling to engineering teams to store data, and we were an analytics product selling to marketing teams,” says Moore. “But a TechCrunch reporter asked me this question: ‘Aren't you scared of Redshift?’”

Moore didn’t flinch. “I was so adamant that these were two completely different worlds. I remember talking to Jake, thinking, ‘This reporter must be on the wrong beat. They're trying to make this a story about Amazon because it'll generate more clicks. They don’t understand how our business works,’” he says.

In hindsight, of course, the reporter proved to be onto something. “They saw around a corner when I was refusing to.”

The solve: Take note of when you’re getting dismissive

Moore’s advice here for founders is to be wary of the tendency to think that you know better than the people in your ecosystem — from customers to investors to reporters.

If you start getting increasingly skeptical about troublesome data trends or industry observations, take a step back and question whether you’re the one obscuring what’s really happening.

When you notice you’re becoming more dismissive of people and things that you think don't know as well as you do, because they haven't been doing this as long as you, it's time to do that intellectual honesty check and see if maybe there's something else going on.

The bias: Selling to people in your network

Moore contrasts the cautionary tale of waning product-market fit at RJMetrics to the powerful early sign that he’d found it at Crossbeam.

To sidestep the cold-start problem, B2B startups launching their products to market typically lean on warm intros and existing relationships for their first few customers. But there’s a downside to that approach: People you know aren’t always going to be honest with you about whether they actually want to use your product.

“Let’s say I take my product to a friend who started another company. He doesn’t want to hurt my feelings, so he’ll pay 50 bucks a month just to make me go away and not have to have an awkward conversation.’ And the tool will sit around and never get used,” explains Moore.

So Moore needed to be careful when gauging interest from his own network — because folks cutting a check alone was not a strong enough PMF signal.

The solve: The show-your-cards test of charging for social capital

Crossbeam is a network-driven software business, which is an approach typically reserved for consumer social networks. The conceit of this growth model is that if all your friends are on a new social network, you’ll want to join too.

But on the flip side, if none of your friends are on it, you wouldn’t be inclined to sign up — unless you’re willing to do the heavy lifting of recruiting them onto it. It wouldn’t make sense for a company to join the Crossbeam platform if none of its partners were on it.

“With a product like Crossbeam, this person that you’re asking to take a chance on you isn’t just spending their own time and their own energy to do you a favor. They’re also expending their social capital,” Moore explains.

This created a pressure test for product-market fit. In the realm of B2B SaaS buying, it’s one thing to write a check — it’s far more telling when people are willing to spend their own precious social capital.

“So if this would have fallen flat, it would have fallen flat immediately. My bluff would have been called the second I said to one of our earliest customers, ‘Hey, I know you said you like this, but can you also invite Zendesk to the platform?’ That's a real ‘show your cards’ moment,” he says.

“By the time we get more than one degree of separation away from me and my personal relationships, that virality has nothing to do with my relationships and everything to do with people being willing to spend social capital just to use the product.”

This is an incredible product-market fit signal: When a customer goes to the most important partners in their business that are responsible for driving a material amount of new sales pipeline or customer retention and tells them, ‘We’re going to use this product, and we think you should use it too.’

A GROWTH-STAGE TEST OF INTELLECTUAL HONESTY: MERGING WITH A COMPETITOR

Founders might bristle at the idea of joining forces with a competitor after years of going head-to-head in the market. But that’s exactly what Moore did at Crossbeam, which recently merged with Reveal.

In Moore’s view, this was the ultimate test of his intellectual honesty — and a far more mature perspective on competition compared to the one he had back at RJMetrics.

Moore shares the backstory for the unconventional decision for two scaling private companies to team up. “Within six months of me starting this company, another guy named Simon Bouchez, who’s a repeat founder based in Paris, started a company that would become Reveal, which was doing basically the exact same thing,” says Moore.

It’d be understandable for Moore to suspect imitation, but he didn’t think that was the case. “I think we came up with the same idea at the same time because we observed the same things at the same moment. He was based in Europe, so they had collected a lot of business in Europe,” he says.

Moore eventually met Bouchez at a partnership leadership event in Miami. The two didn’t even chat about their competing businesses. Instead, they realized how much they clicked. “Our stories, despite being theoretically archrivals out there on the market, were basically the same. He’s like the French version of me. I'm the Philly version of him.”

But the idea to merge companies didn’t come from either Moore or Bouchez. It came from their customers. “I started to notice in our product feedback channel that the number one requested feature from Crossbeam was for us to integrate with Reveal and to support the companies that were on the Reveal network,” says Moore. “We'd host a webinar and people would put in the chat, “When is the Reveal integration coming?”

“It got to a point where we knew we had to put egos aside and do what's right for the customer here. Neither one of us could realize the true potential of our business without coming together.”

For Moore, it was a decision with roots all the way back to when he first started leafing through his digital notebook full of ideas for his third startup. After two middling exits, he was determined to make a much bigger splash — but to hang tight to his original goal of building an IPO-scale business, he needed to let go of his ego.

“What was important to us was making this as big as we could possibly make it, and not having our particular company's name on the business card or going down in history as the one that won the big battle,” he says. “We were both willing to set aside some dilution, some pride and some sense of control to make this one cohesive thing that will actually create what we wanted to create for our customers in the first place.”

This article is a lightly edited version of our podcast interview with Moore on In Depth. Listen to the full episode here.