On a rainy September day back in 2008, Bob Moore took the plunge. He and his coworker Jake Stein quit their day jobs to start RJMetrics, a new company in the data analytics space. While their prospects seemed bright, their timing could have been better — three days later, Lehman Brothers collapsed.

Their startup set out on a journey with just about everything working against it: inexperienced first-time founders, a crushing economic environment and a big bet on where the industry was heading. The path was twisty and full of challenges, but by 2016 the duo had amassed hundreds of customers and RJMetrics was scooped up by Magento.

“But as exits go, it was more of a base hit than a home run,” says Moore. “The most valuable thing we took away from RJMetrics was the muscle of how to fight hard and the painful lessons that came from surviving a turbulent environment — only to later lose the long game. Take our old competitor Looker, which got acquired by Google last summer for $2.6 billion. They ate our lunch, even though we had a four-year head start.” (For more of the nitty-gritty details on where things went south in their battle against Looker, check out Moore’s excellent post-mortem post from a few months back.)

That’s a mistake Moore vowed not to make again. Equipped with a sharper vision and nearly a decade of experience, he and Stein spun off their second company, Stitch, using technology they retained in the RJMetrics acquisition. In just two years, they netted a far better outcome when they sold to Talend in 2018 (with only 30 employees and no outside funding). Now, Moore’s on his third venture — and he’s swinging for the fences. His current startup, Crossbeam, is a platform that aims to help companies build more valuable partnerships through data-driven collaboration. Buoyed by industry tailwinds and nearly $16 million in funding, he and his team seem to have plenty of runway ahead.

While First Round invested back in Crossbeam’s early days (and coincidentally, Looker’s as well), that’s not the reason why we were eager to talk to Moore here on the Review. With multiple startups under his belt, he’s a seasoned company builder — one who has cut his teeth as a first-time founder during some tumultuous times.

“With my first startup, we survived the 2008 downturn and got to an exit, which is more than many startups of that vintage can say. But I was so heads down focused on that ‘grinding it out’ mentality that I over-indexed on it when the time came time to push for growth — and we got lapped by the competition. There's a difference between building a company that survives and one that thrives, and it took me too long to adjust when it was time to switch gears,” says Moore. “Now it seems like the pendulum is swinging back around again to a RIP Good Times mentality. Building a resilient company might be coming back in style, but this time I’m not taking my eye off of the upside that comes after.”

In this exclusive interview, Moore opens up about what he’s learned after more than 12 years in the founding trenches, from building in bear and bull markets to avoiding “meh” exits and tackling the fickle nature of product-market fit. Moore compares his experiences across multiple startups to cull together a collection of seven lessons — the ones he wishes someone had shared with him back when he was treading choppy waters as a first-time founder.

1. A strong long-term vision will help you weather intermittent storms.

To start, Moore stresses that no amount of agility can replace a strong company vision. “A good vision means you have strong first principles. The products can evolve. The team can change. The market could hit a downtown. But if you are relentless and consistent in your pursuit of a well-formed vision, you'll be able to weather most storms," he says. "The difference between having a crisp vision and muddling through without one will alter the trajectory of your company — I’ve been on both sides of that coin.”

RJMetrics was an example of the latter. “We could see an area of opportunity when we got started, but we didn’t actually have a clear vision for what we were trying to build and why it would succeed. We had one word — data — and the rest of our ‘vision’ could twist and turn based on the most recent thing we heard from a lead or customer. A strong vision could have been our backbone, but we just didn’t have it. That was no way to build a category-defining company,’” he says. “Because we weren’t steering with a solid strategy, we pursued all these product micro-optimizations and landed ourselves in a place where we created a company that creates some value for some people. Our growth was stuck on a local maximum.”

Stitch was a different story. At his and Stein’s second company (the one that bagged a better exit), Moore says they had a vision from day one. “Our vision was fully baked when we stepped up to the plate. We said, yes, there's a problem space, but more than that, we have a very specific point of view on how the problem should be solved. It wasn’t just that people were feeling the pain of scattered data, but that we actually had a vision around a solution that would also fit into the market dynamics at the time, specifically how massively scalable data warehouses like Amazon Redshift, Google BigQuery, and Snowflake were coming onto the scene,” he says.

“Plain and simple, here’s the formula you need to nail down: Here's what we’re here to do, here’s why we'll be the best at doing this very specific thing, and here are the tailwinds that make now the right time to do it. We’re seeing this now at my current startup, Crossbeam, too. We started this company with an extremely specific vision for what the world should look like when this data collaboration problem is solved in the best possible way, not with something generic like ‘Partnerships are a pain, let’s go figure that out.’”

What are we going to do? What is our unique vision behind it? That’s an existential, table-stakes prerequisite to building a resilient venture-scale company. Even with the best team in the best market, you’ll hit a ceiling without these ingredients.

2. Product-market fit doesn’t mean you’re in the clear.

Getting to product-market fit quickly is often seen as a panacea for startups, but Moore has learned it's not enough to simply find it — you have to keep it too. “You can’t survive a downturn by shutting your eyes and grasping onto your product-market fit for dear life. Shifts in the market make it even more important to be at the wheel and keep your eyes on the road,” he says.

This was the trap Moore encountered at RJMetrics. “Often people talk about product-market fit as if it’s a video game level you unlock and then it’s smooth sailing from there. That’s a mistake too many founders — myself included — have made. When we started RJMetrics in 2008, I’d say we were ahead of the market. SaaS was still barely a thing, and no one was doing what we were doing. We iterated for four years, onboarding early adopters and building a nice little bootstrapped business,” says Moore.

“And then all of a sudden, the market caught up to where our product was. And that's when we had a crazy product-market fit period. From 2011 to 2013, we couldn’t keep up. The leads were falling off the desk. We couldn’t hire reps fast enough. It was almost unexplainable. We exploded in growth and size, so it seemed like everything was on track. But during that period, we barely changed the product. We became inflexible. The market was moving, but our product wasn’t. So by 2015 or 2016, the market had moved out ahead of us, except we didn’t see it. We kept executing — and got left behind.”

Product-market fit isn’t a diploma you hang on your company’s wall. It’s a moving target that you constantly have to monitor. Take it from me — you can find it, only to watch it slip through your fingers.

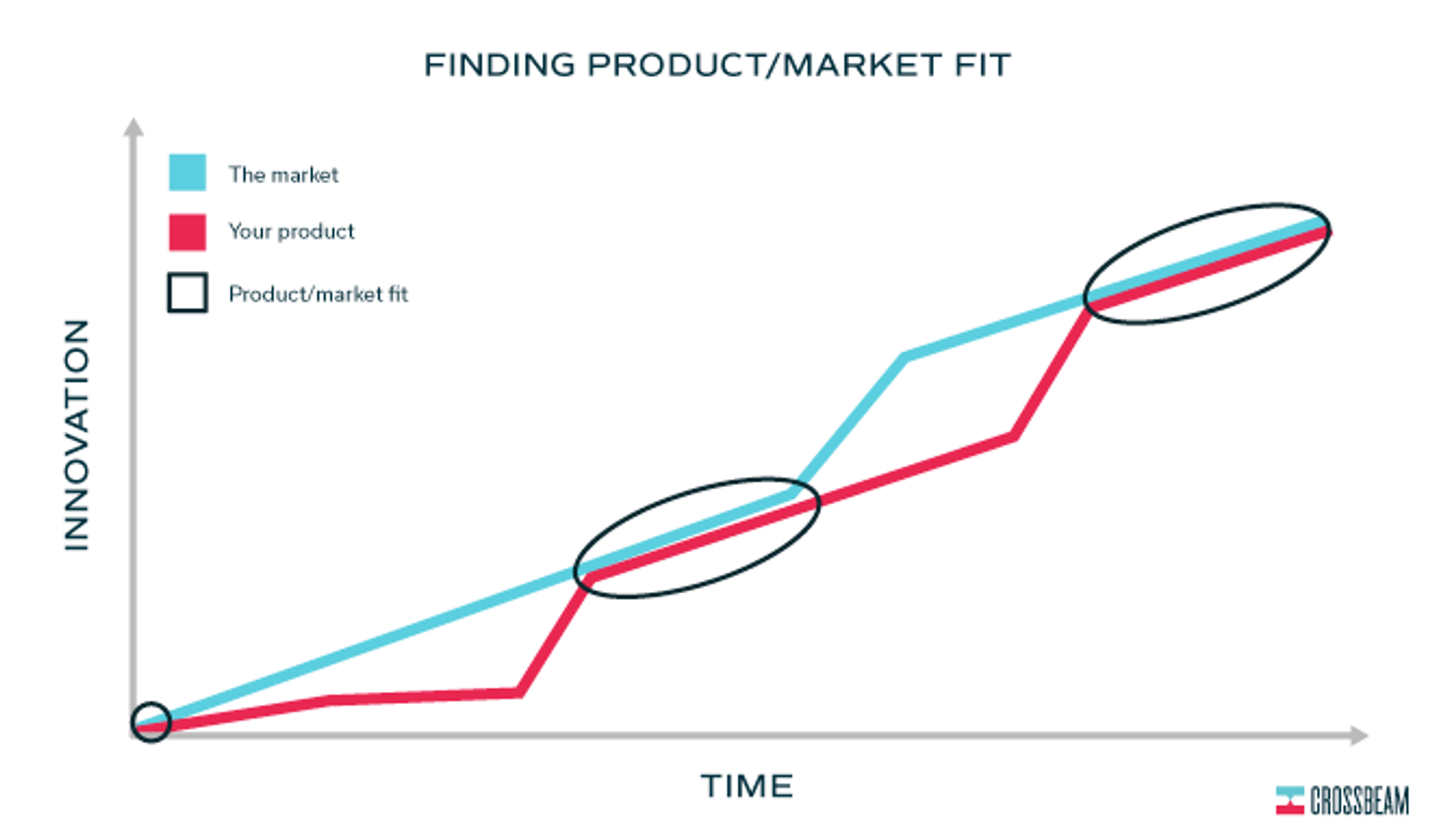

To put it more visually: “Product-market fit is the gap between the product that you built and where the market is at any given time. Picture a chart with time on the X-axis and progress on the Y-axis. Your product and the market are two separate lines with different slopes that move over time. At RJMetrics, they intersected at this beautiful moment, which enabled us to build a lot of value. But then we lost it. If you go long enough without changing the slope of your product to keep up with the market, they will just drift further and further away.”

3. Looking for your biggest competitive threats? Follow signals, not noise.

While understanding your competitive landscape is important, Moore’s come to learn it’s not nearly as crucial as double-checking your company’s path and course-correcting if you fear you’re adrift. The best way to build resilience is to stress test your own assumptions constantly, he says.

This might be a surprising takeaway — after all, given the history, you could forgive Moore for being extra wary of competitors these days. But in his view, RJMetrics didn’t get lapped by Looker because they weren’t paying enough attention to their competitive landscape — they were paying too much attention. “When Looker came out of stealth in 2013, we didn’t even consider them to be our competition. But fast forward six years, and my co-founder and I are scratching our heads about how they won so big and we missed the boat,” says Moore.

“We spent so much time spinning our wheels looking at noisy CEOs and big incumbents. We always had our eyes peeled for that next Y Combinator upstart that would come along and threaten our market position. But in the end our biggest competition came from a group of modest, hard-working operators whose experience gave them a sharper vision,” he says. “For all the young iconoclasts on Twitter, there is an equal number of quiet experts who pose more credible threats. Those were the founders who ended up taking home the gold medals in our industry while we settled for bronze,” says Moore.

The reason they ended up on that lower podium? “We got so heads down in executing on what we thought was a good idea in 2008 that in the course of those next eight years, the ground shifted underneath our feet. This entirely new way to approach the problem came forward,” he says. “I was worried about companies like GoodData and Domo, the ones who were basically doing the same thing we were. What we failed to realize is that Looker was serving the same audience on the same value proposition, with a more appealing product approach. We built the proverbial ‘faster horse’ while they were busy inventing the automobile.”

I don't worry about competition, I worry about my own vision being wrong, which creates an opportunity for competition to succeed. If anything, I think we spent too much energy thinking about the noise everyone else was making and not enough thinking about our own place in the real market.

“To get more tactical, I found it’s helpful to harness that nervous energy and channel it toward something more productive,” he says. “For example, later on in RJMetrics’ timeline, we started asking ourselves a simple question: What's the new product that would terrify us the most if it were launched tomorrow? Our answer was something that could connect the dots between all these new cloud data warehouses that were taking over the market and the emerging tools like Looker that provided a better user experience for analytics. That product would be the missing link in a value chain that would completely disintermediate RJMetrics. Rather than wait for it to show up and finish the job that Looker had started, a small team at RJMetrics built it as a hackathon project. That product ultimately became Stitch, which we successfully spun out and built into a substantial standalone company after RJMetrics was acquired.”

Resilient founders don’t ask “Which competitor are we scared of?” Instead, it's “What fully-formed company would be an existential threat to us, whether it exists or not? And if it doesn’t exist, why aren’t we building it?”

4. Resiliency starts at the top — and it's not something founders can outsource.

While navigating the rough waters of finding a vision, external conditions and product-market fit at RJMetrics, Moore leaned on what he thought was sage startup wisdom: Don’t go it alone. He turned his attention to hiring executives to help round out the leadership team.

“We burned through two VPs of Sales before we figured out that it was product issues — not sales fortitude or go-to-market execution — that was holding us back. So we set our sights on finding the perfect VP of Product to solve our product woes. After months and months of recruiting, onboarding, and testing, it turned out the problems with the product were rooted in the vision of the company,” he says. “We were right back at square one. I wish we’d spent all that lost recruiting energy working on the fundamentals of our vision so those awesome people could have had a better product to build and sell.”

There's a difference between delegating and absolving yourself of responsibility. Don’t let that new, fresh-faced exec be a crutch that causes you to ignore your responsibilities as a founder and CEO.

“As the founder or CEO, you can’t slap on blinders for key aspects of the business. You’re in really, really dangerous territory if you assume that anyone is going to show up and magically fix your functional problems. When you pin your hopes on someone coming in to fix it, what you’re doing is absolving your responsibility to help crack that problem and removing all your institutional knowledge as a CEO. That’s a huge mistake.”

For example, if you’re a technical founder bringing on your first marketer, don’t just wash your hands of this function because you hired someone with experience. “Even if you have no clue how to execute a marketing campaign, you don't know all the acronyms of online ad buying, and you don't know what looks good, you’re not off the hook. You still need to build expectations around what they will deliver, a culture that inspires them and the credibility to hold them accountable. You can’t do all that from a distance, especially with a small team,” says Moore.

It’s impossible to outsource the hardest parts of being a founder. Investors and senior hires are not a dumping ground for your tough decisions. No one’s coming to save you.

.jpg)

5. Rethink your approach to remote work.

Since Moore’s built all of his companies outside of Silicon Valley, you might expect him to be firmly in the remote work camp. But that hasn’t always been the case. “My first job was in finance where facetime is everything. That was ingrained in my work habits, so I spent the early part of my career as a founder demanding everyone be in the office,” says Moore. “But I’ve also had the experience of taking out a multi-year lease on an office space that outlasted our company So over time, my mentality changed drastically.”

Moore notes that the cloud-based tools of 2020 are light years ahead of where they were when he started his first company. “The conventional wisdom as recently as five years ago was that you’re either all-remote, all-office, or you’re doomed. That’s changing along with a new generation of collaboration tools and mentality shift among modern workers. Crossbeam is a ‘remote-friendly’ hybrid that keeps office space available for local employees but also has a large remote workforce,” he says.

With unpredictable global events like the outbreak of COVID-19, the trend toward remote-friendly and remote-first workplaces will only continue, Moore says. “It adds to your company’s resilience — whether that’s an economic downtown, office space troubles or an intense travel schedule. When we switched offices early in our journey at Crossbeam, we asked everyone to work from home for a week and faced minimal disruption. Or when we we sent our team to conferences all over the world, we knew the work will still get done because they had that remote-friendly working habits already. Physical location doesn’t cause a gap in efficiency for anyone, and that’s by design.”

The key to making this work all year round is to go all-in, even if some of your team members return to showing up to an office. Here’s a peek at Moore’s remote-friendly playbook, designed to scale, but applicable for teams as small as two:

- Zoom links are required for every meeting by default, and there can be no assumption that your attendees will be there in person, even if they are regularly in the same office as you. Showing up virtually does not require an apology or explanation.

- Make your remote team members first-class citizens. If a benefit, perk or experience is created for your in-office team members, find a way to create parity for those who aren’t in person. That means mailing items given to your in-office team to remote workers — or if you cover lunch for your in-office team, send your remote team a gift card or stipend for food delivery.

- If your leadership team has a tendency to work in company offices, make it a point to have them attend some meetings virtually anyway, especially for big company events like All Hands meetings. "We’ve taken meetings in different conference rooms or worked from home for part of the day to make this happen," says Moore. "This helps them build empathy for the remote experience and develop the sense of inclusion for remote team members."

- Find the places where shoulder taps and overheard conversations are a convenient crutch, and make them obsolete. “This means you need clearly-measured and communicated goals (we use OKRs), repositories for company history and curiosities (we use a #founder-ama channel in Slack), and 'where you need it, when you need it' repositories for key shared knowledge (we love fellow Philly company Guru for this),” says Moore.

6. Assemble your wishlist of would-be acquirers — and start building authentic relationships ASAP.

“It’s a founder trope to say ‘we didn’t start this company just to sell it’ — and we used to say that a lot,” says Moore. “But we drank so much of that Kool-Aid that we found ourselves scrambling when selling became our best option. We failed to cultivate relationships with potential buyers from day one, so when a high-pressure offer came in, we didn’t have the time or the network to spin up a competitive process fast enough. We may have left some serious value on the table as a result,” he says.

“My co-founder Jake Stein nailed this at our next company, Stitch. He cultivated relationships with the CEOs and heads of corp dev at all of our target acquirers from day one. When we found ourselves in a similar situation with that business, he spun up a fast and efficient process that gave us conviction that we were choosing the right deal for our company and our team,” says Moore. “Now, I’m using Jake’s playbook again at Crossbeam.”

“You don’t kick things off by saying, ‘Hey, you might buy me one day.’ You cultivate them by genuinely looking for synergies between what you're doing and what these other companies are doing. That might be a product integration, it might be go-to-market partnerships. It might just be information sharing. But those relationships require a genuine — not manufactured — motive to take hold. They don’t come together overnight.”

7. Turn self-care into a strength to bounce back from failure.

A disappointing exit or a series of tough scrapes can cast a long shadow on your next play. “When you get beat, when your strategies aren’t working, when you have to do layoffs, when you announce a modest acquisition — it’s easy to hang your head,” says Moore. “It’s not exactly confidence-inspiring to see your first venture go somewhat quietly into the night. After the modest RJMetrics outcome, I was questioning whether I could ever raise money again. What was I going to say? ‘Hey, I’m the guy who pounded his chest before, trust me this time?’ It also gets personal, fast. You think, ‘Have I wasted these years of my life?’ or ‘Is my career as an entrepreneur over?’”

As a first-time founder, it’s easy to believe that the only return on investment you get from your startup is the proceeds from your exit. “Turns out the experience was the real payoff,” says Moore. “It wasn’t until I was building my second company that I realized the upside of falling on my face so many times at the first one.”

In terms of how to weather that failure, Moore points to the importance of self-care strategies. (He’s personally come to rely on exercise and improv comedy.) “Don’t underplay that aspect, it’s truly a big deal,” he says. “Sometimes the company's operational failures are actually outputs of the founder succumbing to decision fatigue. Or becoming overly paranoid or personally stressed. Or not having the energy to build the support system that they need to succeed.”

When it comes to bouncing back from failure, there are many factors outside of your control. But all founders are in control of being honest with themselves about what they need to operate at their fullest capacity — and that includes when (and how) to recharge.

Personal maintenance is the safety net that catches you as you’re weathering failure. It’s not just how you protect yourself when things go poorly, it’s how you focus your superpowers when things are going right.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER: THE FOUNDER’S CHECKLIST

This last lesson is particularly top of mind for Moore these days. “I’m trying to stay conscious of how I’m susceptible to these same forces in a different way now. I’m pedal-to-the-floor with Crossbeam, but I don’t have blinders on about what it means to be building a company in the turbulence of 2020. Business fundamentals are as important as ever, and legitimate product-market fit is still the most important input to making those fundamentals scale,” he says. “That long shadow of my previous experience is still there. I'm also a little older now. I have more gray hair and I've got a beautiful daughter at home who deserves a dad who is present and reliable, so I don’t have time or energy to waste,” he says.

“That’s not to say that repeat founders don't make mistakes anymore, it's that you get to make a whole different class of mistakes — including the risk of living in the past. If I had to summarize what’s different now with Crossbeam, it’s that I have more confidence in the basics. More than a decade of muscle memory makes a subset of my day-to-day decisions a bit less fatiguing, leaving more mental energy for looking ahead to uncharted territory.”

To distill all of the work it took to get there, here’s a quick checklist of the resilient founder lessons Moore’s picked up over the years:

- Sharpen your specific product vision instead of tackling general problem spaces. Be able to answer these questions: What specific thing is your company here to do? Why will you be the best at it? What tailwinds are at your back?

- Remember that hitting product-market fit doesn’t mean you're golden. Keep careful tabs on the changing slopes of the market and where your product is — or isn’t — meeting it.

- Take note that your biggest competitors can come from surprising sources. Focus on your place in the market to make sure you’re not creating an opportunity for others to succeed — and ask why you’re not building the competitive product that’s keeping you up at night.

- Learn the difference between delegating and absolving as you bring on executive hires. Don’t try to outsource the tough calls and foundational problems to new blood.

- Be cautious when it comes to long leases and try to broaden your thinking on remote work.

- Cultivate genuine relationships with potential buyers on day one to reduce the risk of FOMO when negotiating a sale on a tight timeline.

- Weather the storms of failure with a strong support system and set of self-care strategies. The most important thing is to not go away unless it’s on your own terms.

Photography by Michael Brand, NSCI Group.