Early January offers a rare moment of clarity in startup life — a brief window when the slate feels clean, the path forward comes into focus and there’s nothing but calendar pages of heads-down execution ahead.

Here at The Review, we have a more than a decade-long tradition of marking this moment by reflecting on the best pieces of advice we heard in the last year. (As OpenAI's Sam Altman just noted, "new years get people in a reflective mood.")

These annual look-backs do more than just catalog advice we shared. As we assemble these collections, patterns start to emerge, shining a spotlight on the questions that came to define this era of company building.

In 2024, the search for product-market fit unsurprisingly dominated founders' minds and, accordingly, our digital pages. Barriers to building products fell and competition rose thanks to the breakneck pace of advances in AI. While a builder’s tools have never been sharper, the fundamentals of getting a startup idea to work at scale remain stubbornly challenging — from the lonely desert wandering of early customer discovery to attempting to read the tea leaves of non-obvious signs of traction.

Despite all the product-market fit advice floating around the startup ecosystem, there are remarkably few detailed breakdowns of how to go about actually finding it. This gap between theory and practice inspired our most ambitious project of 2024 — a detailed product-market fit framework that goes deeper than the traditional binary "have it/don't have it" or “you’ll know it when you see it” yardsticks.

Building on our regular series chronicling different companies’ paths to product-market fit, we drew from hundreds of hours of research and two decades spent partnering closely with pre-PMF founders to map out the four distinct levels of PMF as we see them — from nascent to extreme. It’s a long read, complete with benchmarks, common pitfalls, and tactical advice from founders who've built billion-dollar companies like Plaid, Vanta, Ironclad, and Looker.

In Looker’s case in particular, we were truly able to pull back the curtain. After investing in their seed round in August 2012, we kept an exhaustive file of notes and data documenting the company’s progression through the years, from the first glimmers of nascent PMF in 2011 all the way through a $2.6B sale to Google in 2019. After revisiting this material (and sharing it in great detail), we were struck by how instructive Looker's journey is all these years later, further underscoring that while markets and macro trends may shift, the fundamental challenges of building enduring companies remain.

And "enduring" is the operative word here. Finding product-market fit may be the first mountain to climb, but sustaining momentum at scale requires navigating an entirely different range of peaks. That's why we also shared advice on everything from spotting the anti-patterns that creep into engineering organizations to cutting through the complexity of annual planning to fighting the constant battle against entropy.

Whether it was Replit’s evolution from side project to billion-dollar business, or Linear’s intentionally lopsided org chart, each story we published in the last year represents what we've sought to provide since The Review first launched back in 2013: actionable wisdom that remains relevant whether you're reading it today or a decade from now.

With that spirit in mind, we've curated the 30 most compelling pieces of advice we published in the last 365 days. Some offer immediate utility. Others plant seeds for future chapters. All of them aim to help you build something that lasts.

1. Find your 200% adjustment to unlock extreme product-market fit

We’ll be the first to admit that spanning the product-market fit journeys of five different companies makes our product-market fit framework a lot to mull over in one sitting. So if you haven’t had the chance to read through the whole thing yet, we won’t judge (although we would highly recommend you carve out the time for it). But if we had to pick just one snappy insight that captures what the essay is all about, it's this story from Lattice founder Jack Altman, after he realized he was stuck in Level 1 of PMF.

“The first thing we built was an OKR software tool. We had seen at our last company that quarterly OKR planning was a painful process for companies. But while it was in fact a real problem, we never built software that truly solved that problem,” says Altman.

There were two hints he was stuck: “One, it was really hard to get people to actually pull out their credit cards and pay us. And so a lot of CEOs and people leaders were saying, ‘We'd really like this. We want to manage our OKRs better. Can we try it? But when we tried to get them to pay, it was very challenging,” says Altman.

“The second issue was that once we did get people into the product — even entire teams where the whole company would do an OKR planning cycle in Lattice — the next quarter didn't come easily. They were like, ‘Ugh, we’ve got to do this.’ And then by the third quarter we were like, ‘This is not happening naturally,’” he says.

His advice on how to get unstuck rang true for us: “If you’re stuck, your only way out of the nascent stage is big changes, not small changes. Moving up levels of product-market fit requires more than just incremental steps or giving it more time,” he says. In Lattice’s case, that meant pivoting a few times, eventually landing on the thing that worked, which was performance management.

More often than not, if you're working on something that is not getting great traction, you’re probably not a 10% adjustment away — you’re probably a 200% adjustment away.

And if you’re an early-stage founder and want the chance to dive into the framework (and a lot more), sign up for our waitlist for the chance to join our next cohort of PMF Method, a free, intensive experience to help exceptional B2B founders build epic companies.

2. Ask yourself these tough questions for more rigorous self-reflection

Whether you always refresh your top three resolutions each new year or balk at the ritual, you’ve likely still found yourself in a reflective mood at the start of 2025.

That’s why late last year we set out to crowdsource some fodder for that annual introspection from the sharpest folks in our Rolodex, asking: Which reflection prompts do you find most useful as a way to step back and think about your business, your team or your own leadership?

We heard from some of the most thoughtful founders across the startup ecosystem, from seasoned repeat entrepreneurs to first-time founders eager to build intentionally their first go-around.

While we sourced these questions from founders, anyone looking to dial up their leadership, productivity and craft in 2025 can steal these prompts for self-evaluation. Give the article a read for the full list of 25 questions, but here are a few of our favorites:

- Did the work I do today actually move the needle on making the company successful? - Colin Zima, CEO and co-founder of Omni

- What’s the hard part — and am I working on it? - Wes Kao, former co-founder of Maven

- Are we pursuing this product direction due to inertia or because it’s right? - Eilon Reshef, CPO and co-founder of Gong

- What’s the conversation I’m avoiding? - Johnathan Nightingale, co-founder of Raw Signal Group

- Where are we on the continuum of chaos and control? - Kareem Amin, CEO and co-founder of Clay

3. Seek out conflict to get context faster

Carta CTO Will Larson has dropped by the Review before, and each time delivers a bit more engineering leadership gold. This past year, in one of our most-read articles of 2024, he took a microscope to three leadership “anti-patterns,” or rules that when applied too universally, start to become unhelpful in practice.

These anti-patterns crop up quite quickly when a new leader takes the helm, particularly when moving from big to small. “The number one way that I see new engineering leaders struggle when they come into a new place is that they assume the context from their previous company applies as is,” he says.

Instead, Larson advocates for what he calls “conflict mining” — deliberately seeking out opposing viewpoints and inviting pushback on ideas. When he joined Stripe after leading engineering at Uber, for instance, he proposed implementing the same automated tooling system that had worked well at his previous company. But rather than charging ahead with implementation, he first ran the idea by several senior engineers.

“One of them absolutely hated my automated tooling idea,” Larson says. “At first, I thought, ‘This is a really unreasonable person.’ But later as I dug into it, I discovered he was right. How Stripe did technology was pretty different from Uber. The way I wanted to approach this problem wasn't aligned with that.”

His advice for engineering leaders? Don't limit these discussions to your C-Suite peers. The most valuable perspectives often come from those closest to the problems. “You can usually get buy-in from other executives pretty easily, but it's much more difficult to get buy-in from people with the most context around a given problem,” he says. “Their opinion is most valuable because they are the ones who live in the details. You can't lie to them. They know the truth of how things run.”

Successful leaders come in and ask, ‘How can I change myself to fit?’ not ‘How can I force my entire organization to fit to work with me?’

4. Use these 12 questions in your next product review

We were eager to sit down with Tara Seshan for a behind-the-scenes look at her seven-year product career at Stripe, particularly for a peek at how Stripe has approached going multi-product. Seshan has plenty of experience here — she helped launch multiple products from 0-1 over the course of her tenure, including as the Head of Product for Stripe Billing and as the GM for Stripe Treasury.

To make sure you’re building the right thing, Seshan cites Stripe's processes as one well worth adding to your toolkit.

“Specifically, there is a set of 12 questions that Stripe leaders ask in every product review. And there's a very strict guidance that you cannot move on to question two until you've sufficiently answered question one,” says Seshan. “You don’t get to all of the questions in every review. Sometimes a team will come in and say, ‘I've only answered four, or I answered one through six in the previous review, now let's get into the others.”

The key here is not letting folks skip over some essential context-setting by jumping right into the product experience.

You're trying to build something that wins, and no one gets anything right on the first try. Software is never done and it’s always bad in the first version. But it’s very hard to evaluate it without any context.

Check out the full article for a deeper dive into each of the 12 questions, but here’s an overview:

5. Make sure your early hires pass the button-clicker test

Whether it’s an early hire in the product, engineering, or marketing function, spotting doers to bring aboard your startup is paramount. “You don’t want someone who will come in and say, ‘I need to go hire a bunch of contractors or other full-time employees or an agency to help with this function.’ Instead, look for people who can actually do things on their laptop that produce,” says Dock co-founder and CEO Alex Kracov. So when assessing candidates, he makes sure they all can pass what he calls the “button-clicker test.”

When Kracov joined Lattice as employee #3 and the first marketing hire, he may not have had robust SaaS experience (actually, he had none). But he passed the button-clicker test with flying colors. “I developed a lot of these little weird skills, like learning Figma or Sketch. Or how to actually build a website or set up a campaign. It wasn’t just that I could talk about marketing, but I figured out how to click buttons and actually do things, or if I didn’t know how to do something I’d watch a YouTube video and figure it out,” he says.

One of the biggest mistakes people make with early marketing hires is they have someone who can talk the talk, but when it comes to actually doing things, they have to go hire people to click the buttons.

6. Stay on top of your annual plan (even when it gets upended)

As the calendar turns to 2025, your company’s annual plan for the upcoming year was probably locked in months ago (at least we hope so). But no matter how polished the document looks in the first few weeks of January, there are some inevitable curveballs coming down the pike. Whether it’s a new entrant in the market, changes in your customers’ behaviors, or cutting-edge technology, how do you strike a balance between getting thrashed around by the changing tides, but not so firmly anchored in place?

When Jiaona Zhang (CPO at Linktree) assembled an annual planning guide, she tapped some of the sharpest folks in her network from Linear, Vanta and Notion. She asked the panel of experts how they approach annual planning, including how they tackle disruptions that can throw the plan off course.

Repetition is critical, says Stevie Case (CRO of Vanta). “No matter how small you are or what stage you’re at, create this time, place and cadence for a check-in and a reminder of what you were trying to do in the first place,” she says.

Usually what goes wrong is that you get into the year, people get busy, you get distracted — and the plan goes completely by the wayside. That’s when you fall into this week-to-week, month-to-month pattern of, ‘Well, what should we do next?’ and being reactive to whatever's right in front of you.

It doesn’t have to be some over-engineered process. Here’s a lightweight check-in framework Zhang designed at Linktree.

“We have a scorecard template for each quarter. It has 3-5 of our key cross-functional goals. Every single week we have a scorecard meeting, which is a lightweight check-in where you grade your goal and tell everyone if you're on track, at risk, or off track,” says Zhang. “You come in with a very clear ask about what help you need if you're trending yellow or red. That way, no one is surprised in the QBR. We’re able to make decisions and course corrections as we go. It’s a great way to get moving on things that are unexpected, like a competitor announcing a big launch.”

You can duplicate her template for your own annual planning check-ins throughout 2025.

Duplicate on Notion7. Map startup ideas on a 2x2 matrix of interest and ability

When scouting around for ideas, some founders chase market trends and personal passions. But that’s just one dimension of strong founder-market fit, warns Bob Moore. The best ideas, he thinks, also tackle problem areas where you’re teed up to excel.

When the serial founder decided it was time for startup #3, he wanted a home run — an IPO-scale venture, and not just another build-and-sell situation like his previous two companies. So he dug out his running list of startup ideas to see which one had that level of potential (which included some oddball concepts, like an escape room franchise).

To whittle down his lengthy list, he devised a simple founder-market fit pre-scree — a mental matrix with two dimensions. He posed these questions to himself:

- Intellectual interest in the problem. How much fun would I have doing this? How much would it light up my brain?

- Founder aptitude. What is it about my specific experience that makes me predisposed to being good at solving this problem?

“I had varying levels of where the ideas for my previous companies fell in the two-by-two matrix. I think that was part of why those businesses were base hits, and neither one of them got to an IPO scale,” says Moore.

8. Challenge the “do one thing well” dogma

“Find your narrow wedge, then expand later” is one of those pieces of startup wisdom that’s rarely questioned — but Replit founder Amjad Masad took a different path. While most founders constrain their focus in the early days, Masad deliberately kept his company's aperture wide.

When Masad saw competitors like Glitch going all-in on JavaScript in 2018, he made the controversial choice to build a general-purpose platform instead. He knew he was onto something when Python started gaining momentum in CS101 courses and data science. By staying broad rather than betting on a single language, Replit was perfectly positioned to ride this wave.

The bet paid off: By 2020, they had 10 to 100 times more users and engagement than their nearest competitor. Replit has consistently pushed boundaries, most recently with their AI agent that can build entire applications from just a few lines of text.

It was an agonizing decision to start building for multiple languages because the Silicon Valley dogma is that you should do one thing and do it right.

9. “Chew the cud” yourself

One of the biggest lessons Matt MacInnis learned from sitting atop an org chart (first as the founder of Inkling and now as COO at Rippling), is that executives should get comfortable with being uncomfortable. “The hardest questions are always going to bubble up onto my plate, so if there was an easy or obvious answer, it would’ve been done below me,” he says. “By definition, execs get all the nuclear stuff.”

Yet, when faced with any sort of complex, or high-stakes decision, MacInnis has observed a dangerous outsourcing tendency in the C-Suite. In his experience, this knee-jerk reaction to immediately seek out advice can have two pernicious effects:

- Hazard #1: It alleviates the need to think from first principles. “The hazard of accepting advice is that it can let execs off the hook for thinking about the problem, but it's their job to synthesize and then come up with solutions that apply,” he says. “The point of going to college is not to walk into a classroom and have someone just give you the answer key to the problem set, you actually need to go and do it yourself.”

- Hazard #2: It reinforces the idea that there's a “right” answer. “When you take advice and fully base your decision on it, you have this false sense of confidence in your answer because you got it from some trusted source,” he says.

MacInnis isn’t tossing out advice altogether. He is, however, challenging whether folks should immediately run for counsel whenever a thorny problem lands at their desk.

“You could spin your wheels for days and weeks on Option A and B, if you’re lucky enough to even have options,” he says. “What you eventually learn is: 1) You’re going to have to learn to live with that discomfort and 2) It’s about how quickly you choose an option and learn from it, rather than whether or not you choose the right one.”

As an executive, you can’t give others the grass, have them chew the cud, and give you the milk. You've got to do the work yourself.

10. Put earmuffs on your “happy ears”

Whether it’s pitching an idea for a brand-new startup, a new feature, or a new product, the more you have at stake, the more you’re probably listening for what you want to hear.

As a user research expert, Jeanette Mellinger is in the business of helping founders and product leaders put “earmuffs on their happy ears.” “The moment you hear, ‘Oh yeah, this product is great,’ that’s your alarm right there. Make space for the things you don’t want to hear — those are the ones that will make your product better,” she says.

To avoid falling into the positivity trap, cut out leading questions, says Mellinger. “A leading question is one that we already have an answer to in our minds. We’re not so much asking it to get new information as we are to validate our own thinking.”

In addition to the obvious culprit to avoid any ‘yes or no’ questions, Mellinger shares a couple tips to spot and strike these leading questions before they poison the well:

- Be careful with adjectives. If there’s an adjective in your questions (like “easy”), there’s an implied opinion. Instead, try rephrasing to a more neutral position: “Tell me about this experience…”

- Course-correct with follow-ups. While it’s best to avoid adjective-laden questions altogether, there may be times when you can’t escape asking something a bit more pointed. In that case, Mellinger has two tips. First, give the interviewee an out: “To what extent was this easy if at all?” Next, follow up with the counter: “To what extent was this difficult?” to balance the scales.

Remember, you want to learn the scary things when you’re conducting research — that’s how you avoid spending all of your time developing a product, only to find out that no one wants it.

11. Don’t hire until it hurts

Over the course of building Zapier into a $5 billion company, founder Wade Foster prides himself on bucking trends and avoiding any cookie-cutter advice for scaling a business. This started all the way back on day 0 when he founded the company in Columbia, Missouri, far from the hotbed of high-growth startups.

The contrarian streak extends to its fundraising strategy (Zapier famously raised a single, $1.3 million dollar round — that’s it) and its approach to scaling the team.

“Lots of folks have said to us, ‘You’re growing, you could grow faster if you hired more people.’ I think a lot of companies and investors overpitch growth at all costs, but sometimes that causes a ‘more people more problems’ issue,” says Foster.

As a first-time founder, if we had tried to grow from 10 to 100 in our first year, we would have ruined a lot of stuff inside the business.

Instead, he credits Zapier’s slow-and-steady approach with the founding team becoming true students of the business.

“It meant we did every single job ourselves at the beginning, so we understood every piece of our business. When we did eventually hire somebody in a key role, that meant we knew exactly what was going to help them win. We knew what good looked like and we knew what bad looked like because we had done it ourselves,” he says.

That’s not to say that Zapier didn’t grow at all, but it was a much more moderate curve. “We went from three founders in the first year, to seven employees in year two, then 16, then 35, and then 75. We were more or less doubling every year,” says Foster.

As for when founders should think about bringing someone on? Wait until some piece of the business is completely breaking down. Like when Zapier’s founders were routinely fielding customer support from early morning until late at night, for example.

12. Dodge the shiny-object spiral

You don’t have to page the calendar back far to find when Kareem Amin was still ferociously grinding to find even developing signs of product-market fit. As recently as spring 2022, Clay was still close to $0 in revenue, despite six years of quietly plugging away at its mission to help GTM teams create more personalized outreach with enriched data.

But fast forward to today, and the company counts Anthropic, Intercom, Notion, Vanta and Verkada as its customers, amongst 2,500+ others — a meteoric rise. You might call it a seven-year “overnight success” story.

So, what consumed those first five years of false starts? As Amin tells it, the Clay team frequently fell victim to what he calls “the spiral.” “One of our customers would say something that would seem really exciting and doable — just slightly off from what we were doing. But we would attempt to go for it to get that customer,” he says.

Around and around they would swirl with different use cases, ICPs, and MVPs. Until Amin made a call: They would only focus on outbound salespeople — for real, no distractions.

“That means pick the actual customer that you're talking to, make sure that they have the same title or at least the same jobs to be done, and then really try to sell it to them — without manufacturing new features.”

There’s a tendency when you’re early to be like, “We’re just missing this one thing…” That actually masks the signs of PMF. When the need is large enough, people will buy your product and wait for you to build the rest of the features. That’s actually the main indicator that you have a product that’s worthwhile.

Amin found it helpful to instill serious discipline here. “I told the team that once we agree to something and it's in our sprint planning, nothing will shift it. If you're walking to work and you happen to have a new idea, throw it away. We think of ideas during our planning, and then we commit to it unless the data changes,” says Amin.

13. Don’t get discouraged by an influx of customer complaints

In the very first leg of the journey to product-market fit, founders are typically on the lookout for customer praise, from high NPS scores and renewal rates to rave reviews and enthusiastic word-of-mouth referrals.

But in the early days of building Gong, CPO and co-founder Eilon Reshef fielded some feedback that wasn’t exactly glowing — but nonetheless revealed that their first few customers actually cared about the tool they’d created.

“Our design partners started telling us, ‘How come you didn’t record this call?’ Which is ironic because our vision for Gong was just to record some of the calls and do the analytics from there, and it’ll work the same way. But it turns out sellers and managers were like, ‘I’m relying on this tool to be my eyes and ears and notepad for all of my calls,’” says Reshef.

“Getting so many complaints about our system not recording all calls, which it wasn’t even designed to do, should have given us better indication that it was becoming a critical tool versus just a nice-to-have.”

Criticism is better than people ignoring you, which means they probably don't need your product. If people start complaining, that's usually a good sign.

14. Treat your point partner like a pitching coach

There's plenty of advice out there about nailing your fundraising pitch, but precious little about what happens once you actually make it inside a VC partner meeting. Now that she’s on the proverbial other side of the table, former founder and First Round partner Liz Wessel sees a crucial blindspot that even the most prepared founders miss — one she remembers from her own fundraising days at WayUp.

Whether you’re a first-time founder or this isn’t your first fundraising rodeo, Wessel’s advice is the same: Your point partner (the investor who is bringing you into partner meeting) is your strongest ally.

“Remember, the chances of a venture firm investing in your startup after an initial 1:1 meeting may be something like 5%, and the chances of getting to that first meeting are even lower,” Wessel says. “But your likelihood of getting an investment if you’ve already made it to the PM stage is much higher — after all, the point partner is taking up time from the entire partnership to bring you in, so they should have some conviction that this deal has a high enough chance of happening.”

When I was pitching as a first-time founder, I didn’t realize how “on your team” the point partner often is. After all, by bringing you in, they’re signaling to the whole partnership that they think you and your company are worth the time and effort of a meeting.

To make the most of this relationship, consider asking your point partner to hop on a 30-minute call before your first partner meeting. Here are some questions worth asking of your point partner:

- How much context will the others in the room have?

- What parts of the pitch should I emphasize more, based on who is in the room?

- How long should I spend on founder backgrounds vs the business’?

- What parts should we do more work on ahead of the meeting?

- What parts of the business will the partnership have the most questions or hesitations about?

15. Go beyond your dashboard to unbox your best metrics

“One of the big challenges for product-led growth companies is that it’s very easy for users to sign up, but not so easy to understand what you're supposed to be using the product for and how you get value,” says Rachel Hepworth, who built the growth engine at Slack before taking the helm for a four-year stint as Notion's CMO.

While most PLG companies religiously track activation rates and sign-up metrics, Hepworth chooses instead to hone in on the subtle behaviors buried in the noise that hint at future customer success.

For example, rather than waiting weeks or months to see if users convert to paid, Hepworth recommends identifying early behaviors that signal someone is likely to become a customer. At Notion, these included:

- Inviting a collaborator

- Creating multiple docs within 24 hours

- Signing up with a work email

Find the metric highest up in the funnel that’s reasonably correlated to a free user upgrading to paid.

But Hepworth also warns against settling for easy-to-game metrics. “It doesn't really matter if your activation rate is 70% or 30% in isolation,” she says. “The question is, ‘What does that metric even mean?’ Because you can create an activation metric that's a pretty low bar and then think, ‘Oh, everybody activates, we have a great business.’”

Quick feedback loops are key to making this approach powerful. “To me, it's important that it's something people hit in a week — or even a day. The speed of that feedback cycle is so important,” she says.

16. Add more rigor to your reference calls

Gearing up for a candidate interview, any hiring manager worth their salt puts loads of prep work in — carefully constructing each question they want to ask, and how they’ll size up a meh vs. great response.

Yet when it comes time to pick up the phone and call references, this well-planned approach tends to fly out the window. Instead, hiring managers treat the references as a check-the-box step (merely asking “What did you think of this candidate?”), farming the process out to a recruiting partner or even skipping it over altogether when they’re in a rush to hire.

To help add more rigor to references, we put out a call to startup leaders and operators in our community for their go-to questions to ask during reference calls, assembling our favorites into a comprehensive guide for hiring managers.

Here are a few highlights:

- What is something that [candidate] is better at than anyone else you've worked with in this role? -Nadia Singer, Chief People Officer at Figma

- Would you rehire this person for almost any role? -Anique Drumright, VP of Products at Rippling

- [Candidate] said one of the things they struggled with when they were at the company was [weakness]. Do you recall cases where that got them into trouble? -Sidharth Kakkar, founder and CEO of Subscript

- Can you share someone who maybe doesn’t necessarily get along with [candidate] as well as you do? Why do you think they don’t mesh well? -Brett Berson, Partner at First Round

- Explain the role at length and what success looks like in the first year. Do you think that [candidate] will thrive in that position? -Claire Hughes Johnson, former COO of Stripe

17. Re-frame your category, don’t re-invent

While many startups chase the allure of category creation, Lisa Bubbers found a different path to build a distinctive brand. The Studs co-founder and former Chief Brand Officer discovered that there’s merit in a subtler approach: identifying gaps in existing markets and positioning your solution as the missing piece.

As the architect behind the D2C piercing brand beloved by “zillennials,” Bubbers didn't try to convince customers that Studs had invented ear piercing. Instead, she focused on reimagining the entire experience — from piercing to aftercare to styling. “I knew I needed to make it clear that what we're doing is different than just going to the tattoo shop around the block,” she says.

To package and present Studs’ value prop, Bubbers made two strategic moves:

- First, she trademarked the term “Earscaping” to give customers language to describe the complete piercing journey.

- Then, she launched “(Ear)ducation,” a comprehensive content hub on their website.

When you’re building in a new category or inventing something entirely new, invest in brand, content and audience education first. When it clicks for people and they understand what you’re making, that's when you become a category leader.

18. Invest in your 10-minute managers

When Anna Binder first joined Asana in 2016 as an HR executive, the startup had just closed its Series C and was in the midst of startup hypergrowth. But its talent strategy was still pretty bare bones: hire a lot of great engineers, and do it fast. As a result, Binder stepped into an org full of what she calls “ten-minute managers” — folks brand new to management, who are trying to assemble their arsenal of tools as quickly as possible.

She learned that one of the trickiest skills for these new managers to grok was delivering constructive feedback. It’s no easy task, but for startup leaders, it’s essential. “If you're not uncomfortable giving feedback every single week, you're not doing your job,” she says.

So one of the first things she did was bulk up new manager training to include lessons on how to deliver blunt feedback. “Studies show that high performers are twice as motivated by constructive feedback than the average employee,” says Binder. “And when I say constructive, I don’t sugarcoat it, I’m talking negative feedback.”

It’s a virtuous cycle, she says. Invest in your managers and teach them how to give constructive feedback, then they’ll do that for their highest performers, which will motivate those people and grow them even more.

But re-vamping, or even implementing new manager training isn’t always an option, especially at early startups, so one thing founders can encourage their managers to do is to hold a weekly self-reflection.

Every Friday afternoon when they’re finishing the week, managers should be asking themselves, “Was I uncomfortable this week? Was I giving hard feedback?” If the answer’s yes, then they’re helping support culture.

19. Schedule distance to see the forest

It’s a tell-tale sign of a first-time founder: flexing about pulling 80-hour weeks and working through weekends. But when Dennis Pilarinos reflected on his biggest lessons learned as a second-time founder hammering away at 0-1 again building Unblocked, it’s that sometimes the best way to solve problems is to step away from them.

“Now I have evidence that distance from the problem helps you solve it better,” Pilarinos says. “When I take a day away from the things I'm mulling over or that I just can't seem to wrap my brain around, I come back to the problem and it's simpler to resolve.”

After burning the candle at both ends with his first startup, Buddybuild, Pilarinos now blocks off Saturdays entirely — no phone, no computer, no work. “As a first-time founder, it was foreign to me that other people wouldn’t be going into the office on a Saturday, as I had done so for so long,” he says.

This simple buffer has helped him stay at equilibrium amidst the high highs and the low lows of startup life. “You're never as bad or as good as you think you are,” he says. “It's easy to say, but really hard to internalize. And so on the days that you land that big deal, you're like, ‘I'm invincible.’ And then when the system is down for an extended period of time or a demo goes poorly or a customer churns out, you think, ‘Well, this is the end of the world,’” he says.

When you can see what’s a tree from what's a forest, everything becomes a lot clearer. It's counter to the feeling of perseverance, where you feel if you keep hacking away at this one thing, you'll eventually figure it out.

20. Run sprints to find your growth levers

If you knew for certain that you would need to make 1,000 wrong moves in building an early-stage startup to unlock hockey-stick growth, how would you run your business differently?

That’s the question SYSTM’s Matt Lerner posed to us this past year. “In the early days of any startup, you need to learn a bunch of things the hard way. Why not do that as fast as humanly possible?” he says.

In his new guide on the Review, Lerner shares his tested process for running growth sprints that don’t waste time on small, incremental ideas and instead take big swings. Airbnb wrote a script to automatically post each new listing to Craigslist. Canva created thousands of SEO-optimized pages with templates and tutorials. These are the 10% of ideas that generate 90% of an early startup’s growth, says Lerner.

“Big companies can grow by deploying heaps of cash and armies of people, using every channel, hoping one will work, and not really understanding which ones do. But startups with a few employees, a couple million dollars, and 1–2 years of runway don’t have that luxury. They need to find the small actions that bring huge numbers of customers, quickly,” he says.

For startups, finding big growth levers is a matter of life or death. Most startups never find them, and they die.

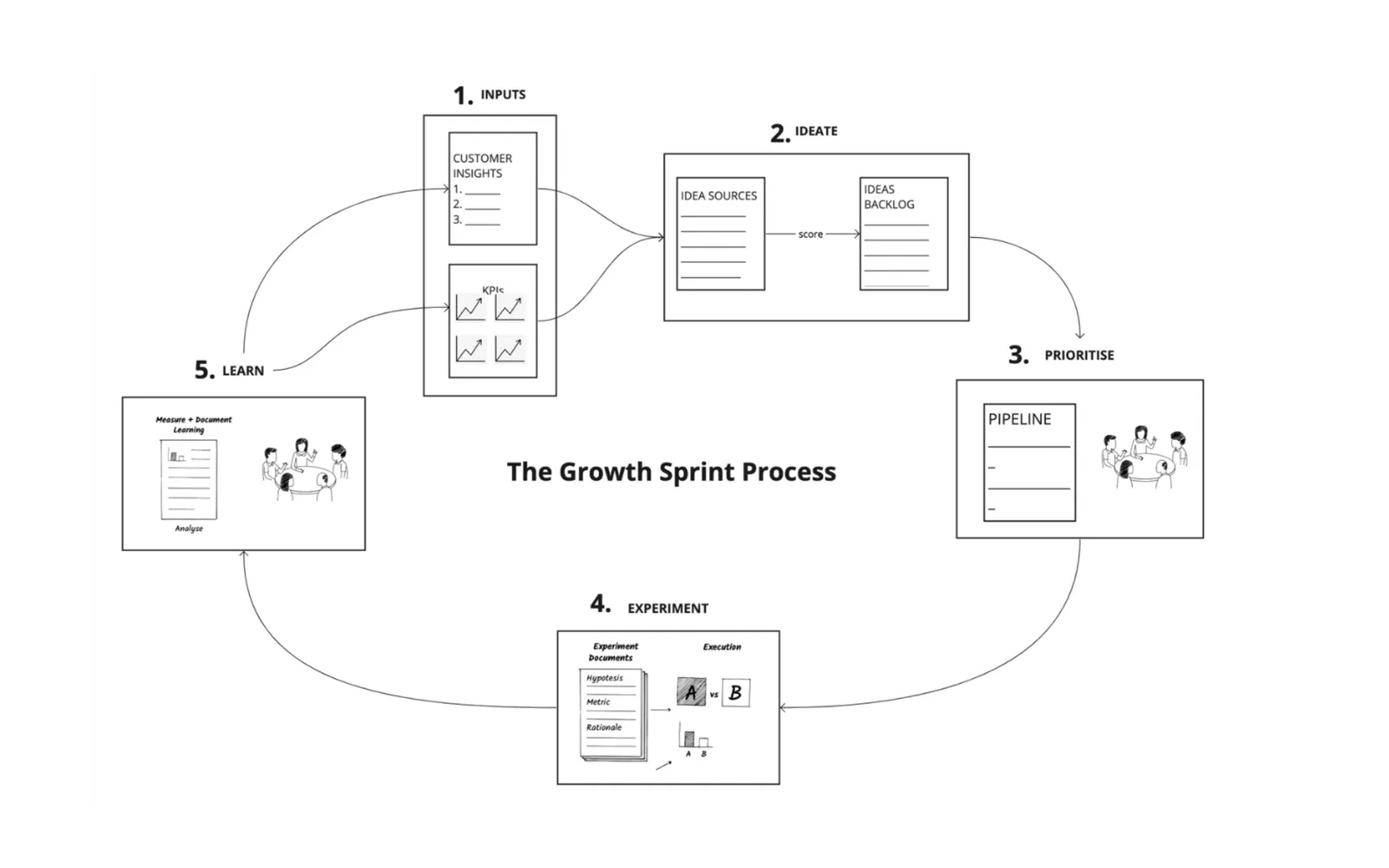

The full article is a must-read to break down the entire growth sprint process, but here’s a brief overview of the five-step process:

- Inputs: Gather your customer insights and the data in your growth model, plus any past experiments or ideas.

- Ideation and Scoring: Triage your ideas to create a shortlist for consideration in the current sprint cycle.

- Selection: Select the most promising ideas to test.

- Experiment: Design and run your experiments.

- Learn: Learn from the experiments, document, and share your takeaways.

21. Floor it — but not without checking your GPS first

At this point, it’s a platitude to say that startups must go fast. But speed without direction just means you’ll get lost more quickly.

Vercel founder and CEO Guillermo Rauch boils down his mindset during the earliest days of building the front-end cloud service to this: “Focus on iteration velocity, rather than speed. Velocity is speed with direction — you know where you're headed,” he says. “Or even if you don't know where you're headed, you're seeking direction. It doesn't mean you're just writing code 20 hours a day and churning out features left and right.”

For Rauch, that meant building software that’s directionally informed, even if it required slowing down to listen to customers. “The ways that this has shown up in my career is that sometimes the solution was to build less and focus more. Sometimes, it was to really pay attention to what customers were trying to tell us. For someone who loves to move fast more than anything else, I think that was the right complement that I needed to add to my framework to be truly successful in a durable fashion. In the early days, finding that direction was the most important thing you could be doing.”

22. Practice good data hygiene before you have an analytics team

Jessica Lachs, Doordash’s Chief Analytics Officer, stopped by the Review to share what she’s learned from leading all things data at the company for the last decade, from scrappy startup through IPO.

Her biggest piece of advice? Don’t procrastinate setting up good data habits while your startup is still young.

In the messy early days, Lachs recommends keeping things simple, laser focusing on the core metrics related to product-market fit. The exact metrics will vary, but for most startups, they’ll be:

- User acquisition

- Customer engagement

- Revenue generation

- Operational efficiency

But growth can catch you off guard, and before you know it, you have thousands of customers and reams of data, and you need a few dedicated analytics hires — yesterday. If you answer “no” to these questions, it might be time to stand up a formal team:

- Do you think you’re measuring the right metrics?

- Do you have measurable goals for each area of your business?

- Do you understand the value drivers of your business — what moves the metrics you’re measuring?

- If your business performs better or worse than expected, do you understand why and how to accelerate or course-correct?

- Are you searching for new growth or profitability opportunities?

- Do you feel comfortable with how you prioritize initiatives for the greatest business impact?

- Do you understand the economics of your business and how your pricing or discounting may impact the tradeoff between growth and profitability?

- Are you using experimentation best practices to inform decision-making?

23. Decentralize your community-building efforts

When startups think about building community, they often imagine a carefully orchestrated, top-down effort. But Notion, now famous for its expansive global community, took a radically different approach in its early days.

Instead of trying to control every aspect of community building, founding Head of Community Ben Lang decided to do something that seemed risky at the time: Hand over the reins to their most passionate users.

We never had this top-down approach to community that constrained people in a box. Our approach has always been to encourage people to do amazing things with Notion and empower them to share what they've built.

As he explained to us in our insider’s guide to Notion’s marketing engine, rather than dictating how community members should represent the brand, Lang and his team found enthusiastic users who were already creating content or hosting events around the product. This was the genesis of Notion’s Ambassador program.

It was a relatively low-lift strategy, which was great for an early-stage startup at the time. All Notion had to do was provide resources and support — early access to features, event funding grants, exclusive Slack groups — while letting ambassadors completely own their platforms, whether that was “Notion Korea” on Facebook or “Notion for Artists” on Telegram.

The counterintuitive strategy paid off. Today, Notion has a global network of 300+ ambassadors running community-led events almost every day around the world. By decentralizing control and focusing on empowerment rather than enforcement, Notion built a community program that scaled far beyond what their internal team could have achieved alone.

24. Make a (lopsided) org chart you want to ship

When designing their org charts, most startups optimize for looks over taste — breaking their product teams into neat, symmetrical squads of 5-8 people, like perfectly round grocery store tomatoes. But according to Linear's Head of Product Nan Yu, this aesthetic perfection often comes at the cost of flavor. “A nice, perfectly symmetrical org chart should raise your suspicion. Because it tends to spread your attention everywhere,” he says.

Yu advocates instead for building an “heirloom tomato” org chart — one that might look irregular and lopsided, but packs more punch where it matters. “If you're a startup, chances are there are a few things that make your product truly different,” he says. “These are the areas to over-provision. Leave enough slack on those teams. Not just to build the first version. But to deal with inevitable user feedback, maintenance, bug reports, and polish.”

At Linear, rather than splitting their initial dev team at every opportunity, they let it grow large — with the core product function eventually accounting for more than 50% of staff. While this creates more management overhead, it allows the team to maintain high quality even as the product scope increases. “We're not passive portfolio managers. We're making active product investment decisions constantly,” Yu says. “We have two large strategic planning moments per year, but we're effectively re-evaluating our near-term roadmap every 3-4 weeks.”

Teams and scopes don't need to be divided along a uniform dimension. They don't need to be mutually exclusive or narrowly defined. Those are made up of constraints in service of symmetry.

25. Steal marketing ideas — just not from within your domain

When brainstorming ideas for your next marketing campaign, your first instinct might be to take a peek over the fence at what your competitors have been up to.

But Krithika Muthukumar, who’s led marketing at Stripe and OpenAI, would urge you to stop looking over your competitors’ shoulders for marketing inspiration. She’d even give you license to copy a cool idea — so long as it comes from a totally different field.

“At Stripe, we borrowed ideas from people who were doing things well, but very much from outside of our domain. So we would never try to one-up our competitor,” she says. “We would steal copiously from domains as far ranging as healthcare to people who were launching new programming languages to the security field.”

Muthukumar offers an example of a security-inspired Stripe campaign that grabbed a ton of attention. “We launched a Capture the Flag tournament at Stripe, and that's typically for InfoSec researchers and Black Hat areas of security research. We did that in the payments domain, and we had no expectations of how many developers would participate. But at its peak, we had about 10,000 people go through the entire five different levels of the Capture the Flag challenge,” she says. “Many of the victors went on to become Stripe engineers.”

If we had copied from our competitors, it would have felt pedestrian — and minimized what otherwise could be possible with the brand.

26. Pass the expansion marshmallow test

As you expand, you may need to make some tradeoffs that sacrifice short-term gains in favor of more long-term growth investments. This was the conundrum Pinterest’s team faced as they tried to expand into international markets. While U.S. growth was booming, international was nearly non-existent.

“It was always easy for the team to run an experiment that moved U.S. growth a couple of percentage points,” says Casey Winters, who was the Product Growth Lead. “So naturally, that's what everyone spent their time focusing on — instead of worrying about getting Brazil from zero to one.”

“So it was the marshmallow test: Are you going to eat that marshmallow in front of you or wait and get the second marshmallow later on?” says Winters. “And even if the founders pass the marshmallow test, it can be hard for everyone else in the organization to pass the test too.”

Finally, founder Ben Silbermann put his foot down. He told the company that metrics needed to be goaled in five non-U.S. countries. In the meantime, they would move their focus from U.S. growth — and if those metrics dropped a little, so be it.

It's incredibly hard to get a team working on a product that has product-market fit to shift to something else that's not going to show immediate return.

27. Avoid the “two-call” dance

As a first-time founder, sales is one of the most daunting hurdles ahead, especially for technical folks. To add some training wheels, it's tempting to over-engineer your pitch process. But Christina Cacioppo, who founded Vanta with zero sales experience (“The last thing I sold before starting the company was Girl Scout cookies,” she quips), learned that sometimes the simplest approach works best.

Her initial strategy was to split customer conversations into two calls:

- One for discovery and basic explanations

- Another for a product demo.

“I thought I was all set with this genius two-call sequence,” says Cacioppo. But a blunt prospect set her straight: “That should have just been one call where you showed me the product immediately, and the deal would've been done in 30 minutes.”

Instead of elaborate sales sequences, Cacioppo found success by targeting fellow founders and getting straight to the product demo. “It helps to sell to other founders because they're much more tolerant of the ‘let me show you what I built before I give the sales pitch’ approach,” she says. “They've been there, so they're much more motivated by talking about a product than being sold on it.”

28. Build what resonates for customers — not just yourself

Pilot’s founders had stumbled on a problem — one that initially popped up when they built their first company nearly a decade earlier. “The overwhelming, loudest theme that came out of customer discovery was that getting your finance and accounting taken care of was as unsolved a problem in 2017 as it had been back in 2009 when we were at our first startup and trying to do it ourselves,” says Jessica McKellar.

As seasoned entrepreneurs with two exits under their belts, McKellar and her co-founders Waseem Daher and Jeff Arnold could smell a winning idea and lasered in on building a bookkeeping and tax services company for startups.

The three MIT-trained computer scientists (“the nerdiest of the computer nerds hung out at the computer club, and that’s where we met,” jokes McKellar), could’ve built a pure software solution. But by doing so, they would’ve missed the mark of what their customers were actually telling them.

“From talking with business owners and founders, nobody was saying, ‘Hey, I want more accounting software.’ People were saying, ‘I want to give this problem to someone else and have peace of mind that it’s being solved,’” McKellar says. “The feedback was that they wanted someone else to own the problem from end-to-end.”

It’s a hard-won lesson from their Zulip days (their second company together) when the founders built the product they wanted as engineers, not the one that a wide swath of customers wanted. This course correction turned out to be part of the winning strategy that has propelled Pilot to a $1.2 billion dollar valuation.

You have to be really careful about overfitting to your own experience. You need to make sure that you're selling something that is going to resonate with the intended audience.

29. Skip the written memos — get your startup’s lawyer on the phone

Legal affairs can feel like a nagging necessity for founders — expensive, time-consuming, yet crucial for long-term success. Especially when just starting out, early-stage founders want to use their untapped energy to hit the ground running, not toil at a desk filing incorporation documentation or thumbing through compliance paperwork.

After years of bridging the gap between fast-moving founders and conservative legal counsel, Irene Liu has become somewhat of a legal translator between these two very different worlds (most recently as Chief Legal Officer at Hopin).

She shares a counterintuitive piece of advice that can help startups maintain velocity while keeping legal costs in check: skip the written memos.“Jump on phone calls wherever possible because it will be far more efficient,” Liu says. “You’ll be able to quickly ask any follow-up questions. It will also cost less since it takes less time to answer a question by phone than by email.”

If you absolutely need something in writing to better digest the information, Liu says to ask for a one-page executive summary instead of a full memo. And remember, if you find yourself hitting a wall when you’re working directly with law firms, then there’s no reason you need to stick with them. “A founder/lawyer relationship is like a romantic partnership. The right fit often comes down to chemistry and communication,” Liu says. “If things aren’t clicking, break up and move on.”

30. Be wary of innovation saboteurs

“Innovators often assume that their industry will welcome new ideas. Unfortunately, the world does not unfold like business school textbooks.”

It’s a bit of an ironic quote from an adjunct professor at Stanford University, but Steve Blank is no ordinary academic. His career has spanned eight different startups and his book “The Four Steps to the Epiphany” is a seminal text for entrepreneurs.

And he’s a frequent first call for founders facing down potential company-killing catastrophes — like being blocked at every avenue as they try to sell into a government agency or getting slapped with a patent infringement from a Fortune 500 competitor.

“Incumbents use a variety of ways to sabotage and kill innovative ideas inside of organizations and outside new companies. And most of the time innovators have no idea what just hit them. And those that do have no game plan in place to respond,” says Blank.

Founders and innovators within bigger companies alike should expect that existing organizations and companies will defend their turf — ferociously.

Whether you’re a new entrant taking on an established competitor or you’re trying to stay scrappy while operating within a bigger company, here are a few of the most common methods of sabotage that Blank has seen from incumbents

- Create career FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt). Positioning the innovative idea/product/service as a risk to the career of whoever adopts/champions it.

- Emphasize the risk to existing legacy investments, like the cost of switching to a new product or service or highlighting the users who would object to it.

- Claim that an existing R&D or engineering organization is already doing it (or can do it better/cheaper).

- Create innovation theater by starting internal innovation programs with the existing staff and processes.