Many founders spend years searching for product-market fit. For some, product-market fit finds them.

In 2016, Tristan Handy opened up a small consultancy with modest ambitions: help startups shore up their data systems. He and his co-founder quickly pulled together an internal product — which they dubbed the data build tool, or dbt — to speed up their consulting work.

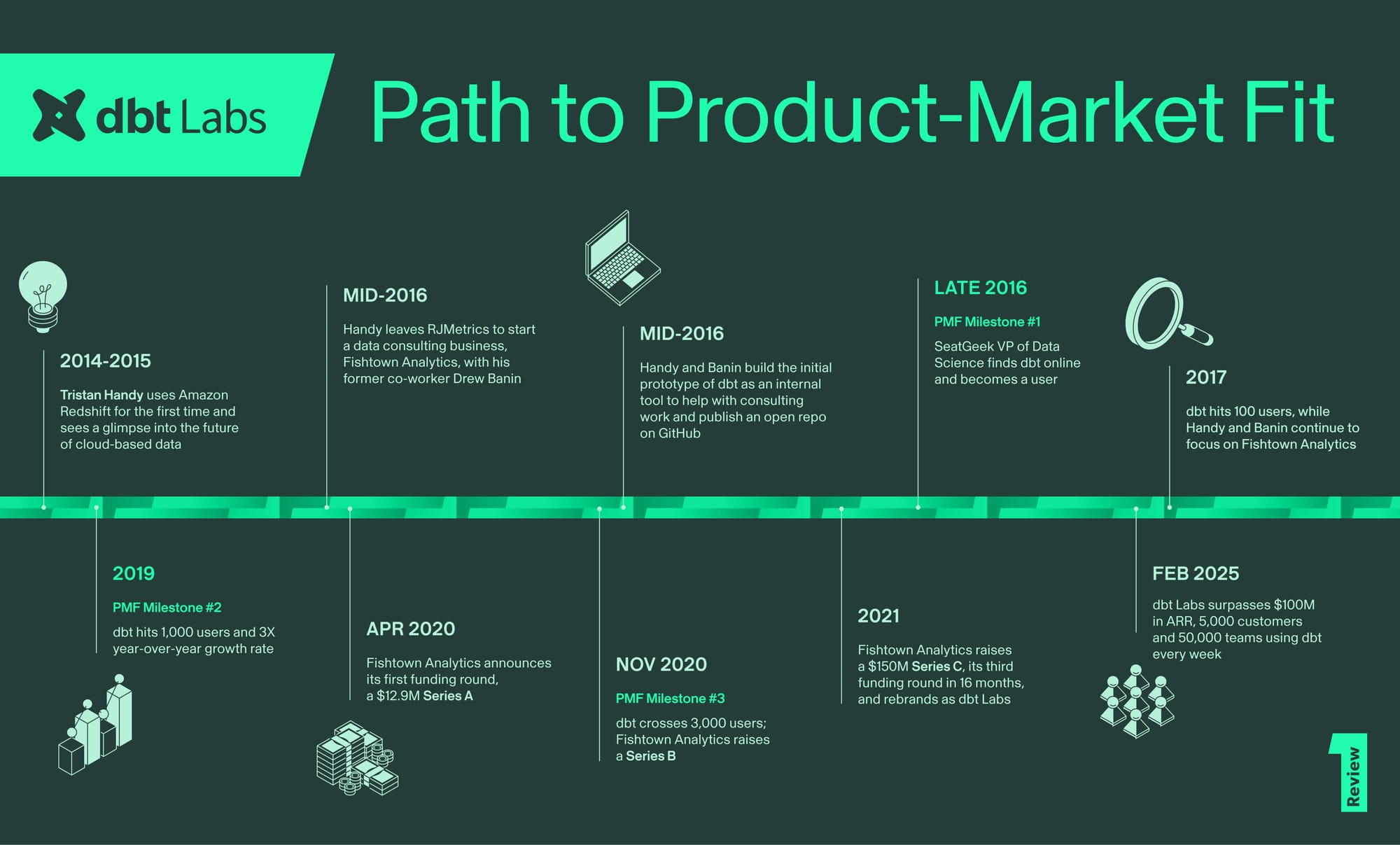

Almost a decade later, that tool would morph into a $4.2B cloud-based analytics engineering platform used by more than 50,000 teams every week. Today, the company behind it is known as dbt Labs (which recently cleared $100M in ARR).

Handy never expected he’d be sitting at the helm of a billion-dollar venture-backed company, or even a consultancy, for that matter. Despite stints at several startups, he never harbored dreams of one day starting a business of his own. His entrepreneurial journey began instead while he was working at analytics tech startup RJMetrics — and he fell in love with the cloud-based tech that ultimately pushed him to strike out on his own.

He left to start Fishtown Analytics, named after the Philadelphia neighborhood that he called home. Within a few weeks of running the consulting business, the founders had developed dbt for their own use. They threw up an open-source repo, thinking maybe a few folks might find it interesting, and got back to work with clients.

Turns out the tool had a much larger audience than just Handy and some data nerds on GitHub. Over the next three years, dbt’s word-of-mouth traction spread online and it quietly amassed over 1,000 users — growing 3X year-over-year. By 2019, Handy reluctantly agreed to raise some money to scale the free tool’s organic growth, and in 2021, rebranded from Fishtown Analytics to dbt Labs, leaning into the tool’s breakout success.

“I didn't want to take venture funding, but it was so clear that we were doing the product and the community we’d built a disservice by under-investing in it,” says Handy. “We had three engineers supporting a thousand companies. It was widely used and yet totally under-resourced.”

Pivoting from consultancy to SaaS business was an uncommon move, but it had its merits. By the time Handy signed his first term sheet, he already had inroads with dozens of startup data teams and a community engine behind dbt.

Here, Handy opens up about dbt Labs’ unconventional path to product-market fit, sharing all the twists and turns from the company’s start as a two-man consulting shop. This is a worthwhile read for aspiring entrepreneurs who aren’t quite sure if the VC route is for them — a reminder that there’s no fixed path to building an enduring business.

Bootstrapping a consultancy

Handy spent the first decade of his career leading analytics functions at Deloitte and Squarespace, and eventually RJMetrics, where he served as VP of Marketing for several years. Then, in 2015, the advent of cloud-based data shook up the market.

He got access to Amazon Redshift and within two queries, he knew it was going to change everything for his profession. “The performance was orders of magnitude faster than the analytical products that I had used previously,” he says. “Before Redshift, you had to be a large enterprise to get access to that kind of performance. All of a sudden, you could swipe a credit card and pay $160 a month for this class of technology.”

Handy could see the technology landscape shifting under RJMetrics’s feet. “We would have never been able to anticipate the rise of the cloud for data specifically,” he says. “We were supposed to become what Looker became. The cloud came for us and disrupted our entire business — it created an opening for Looker to steal the exponential growth curve we were sitting on.”

Handy was so floored by the technology that he was excited to help startups take advantage of cloud-based data platforms. But he didn’t want to start a VC-backed company to do it. The threat of failure loomed too large.

“When everything goes well for a VC-backed company, it's great. But often, it doesn't go that well,” he says. “Being a leader at an organization that’s not winning brings an unbelievably high level of personal stress. You fundamentally feel like you’re not in control of the process because you have investors who have expectations.”

So Handy figured a consultancy was a less risky place to start, but even that option was daunting. He struggled to picture himself as a founder.

“I'd never started anything before. I'd worked for three other founders, and always had this idea in my head that founders were a different type of person, and I was not that type of person,” he says. “This was the era when The Social Network was made, which convinced people that founders were supposed to be college dropouts who’d pound on the table and say, ‘We're going to change the world!’”

Other doubts clouded his head. “I was afraid of having to tell all my friends and family that I tried and failed at something,” he says.

So he floated his idea for a consultancy with the founders he’d previously worked with, which ultimately helped ease his impostor syndrome.

In retrospect, Handy thinks his hesitation around starting a business was a useful way to keep his priorities in check. “Instead of being so attached to the outcome of building a company, I was attached to the outcome of solving a problem in the world,” says Handy.

If you’re so obsessed with this problem that you couldn't imagine not spending all your time on it, you increase your chances of actually being financially successful. The success of your company has to be downstream of that.

With his founder friends’ encouragement, Handy felt more optimistic about starting Fishtown Analytics. And to minimize his own personal risk, Handy wrote a $10,000 check out of his own wallet and deposited it in a bank account. “Worst case, I could lose some months of my life and 10 grand. It wouldn't be the end of the world,” he says.

Bringing on a co-founder

Given his own misgivings about starting a business, Handy was reluctant to find a partner for his new consultancy at first. He didn’t want “another mouth to feed,” as he puts it.

Then Drew Banin came back onto Handy’s radar. Banin had worked part-time at RJMetrics as a software engineer to pay his way through college and was finishing up his degree at the time. He caught wind of Handy’s new business — and rather than lining up a gig post-grad, he made a pitch to join.

“Right around when I was starting, Drew pulled me aside and said, ‘Hey, can I help?’” says Handy. “I was pretty resistant to that at first. Not because of Drew — he’s freaking incredible. But the idea that I had another salary to pay when I hadn’t even closed my first client was stressful. I just hoped I could figure it out.”

Landing the first clients

Now with two paychecks on the line, Handy needed to grow the book of business, fast.

His deep familiarity with the needs of SaaS and B2C companies informed a natural client profile. Fishtown Analytics’ first two clients were folks he’d met through his work at RJMetrics. “It felt obvious. I knew e-commerce and SaaS, and I knew how many e-commerce and SaaS companies there were because I'd actually done the market analysis at RJMetrics,” he says.

Here’s how Handy thought about finding clients:

- Stick to a super specific client profile to make new business repeatable. All of Handy’s early clients fit the same bill: Series A, B or C B2C or SaaS startups, and specifically their CEOs or VPs of Marketing, who needed to understand their data. “This is something that people who build consulting companies get wrong: They accept whatever work comes their way.”

- Clearly articulate to clients how you’ll create value and save them money. Handy pitched Fishtown Analytics as a lean stand-in for an entry-level data analyst. “We said, ‘Look, we’ll produce more value for you than if you hire internally,’” he says. “Our annualized rate was something like $60K a year. We knew we could deliver a really unbelievable amount of value very quickly without a lot of consulting dollars.”

The nature of this consulting work meant Handy could hire and train younger talent, like Banin, to join the crew. “If you drop a consultant in and say, ‘Go solve these random data problems with this startup executive,’ they need to have 15 years of experience. But if you say, ‘Hey, this is exactly the set of problems you're going to solve, and here are some instances where we've solved this before,’ you can have somebody brand-new in their career do that.”

There isn’t a “venture-scale exit potential” in a consulting business, but there is a really satisfying founder-scale potential.

Crafting — and open-sourcing — a dbt prototype

As Handy and Banin got Fishtown Analytics off the ground, they had scrapped together an early prototype of dbt. They saw it as a means of boosting their own productivity as consultants — so they expected to be the tool’s only two users.

At the time in 2016, Handy felt there was a missing category in the data process known as ETL: extracting, transforming and loading data to be analyzed. Plenty of software companies handled the bookends of extract and load, but there weren’t many tools built for the transformation in the middle that cleans up data to be used. “In order to do good consulting work, I felt strongly that we needed a tool,” he says.

The premise of dbt was this: Analytics as software, authored by anyone who knows SQL, to bring together the best of both worlds of analytics and engineering.

Handy didn’t think there were many other data pros with the hybrid data and technical skills he had who’d be equipped to use dbt. “It was so different from anything that existed before,” he says. “Data tech prior to 2016 treated data analysts as low-level, non-technical people. You can see that in Excel or Tableau — you could do powerful things with these products, but the interface is more drag and drop.”

Handy even told a few friends in VC about the tool he was building, and they agreed that there probably wasn’t a big market for it.

VCs told me, “dbt sounds interesting, but you might be an N of 1 user who wants something like that.”

So Handy and Banin built a quick and dirty product that was immediately useful — without sinking a ton of engineering hours. Banin had the stronger coding chops of the pair, so he was able to whip up a prototype on nights and weekends.

The initial version was bare-bones and had no fancy UX. “We had a version that had roughly two weeks of engineering time put into it on day one,” he says. “When you build command-line tools, you don’t have to build a user interface or a login, so you can get a lot of value out of a small amount of effort.”

So they kept the tool fully behind-the-scenes to clients. “If we'd tried to convince people to use this piece of technology that nobody had ever used before, it probably wouldn't have gone well,” says Handy.

But Handy and Banin were happy users. “This is an unscientific number, but I’d say we could deliver work at least 10 times faster than we would have been able to do otherwise. It was the magic silver bullet that made the entire consulting model work.”

dbt was open source from its inception, when just Handy and Banin were the lone users.

“When we first built the initial version of dbt, we stuck it in an open repo on GitHub and put an Apache 2.0 license on it so that it was just out there, available,” says Handy. “Early users started telling their friends about dbt. People would just find it.”

This might sound like a counterintuitive move for a tool developed for Handy’s and Banin’s own benefit. Handy says his decision to open-source the software instead stemmed from a commitment to knowledge sharing. “We didn't know that a ton of people were going to use dbt, but we thought it was a good idea, and maybe some other people out there would find value in it,” he says.

Building an ecosystem

Once Handy had two clients signed, he didn’t need to rely too heavily on the Rolodex he’d built from over a decade in the data space. Instead, he leaned into marketing and community building to drum up inbound leads.

Here are a few of the moves Handy made that buoyed Fishtown Analytics’ and dbt’s word-of-mouth growth in tandem:

- Betting on content marketing from day one. Most people who start consulting companies don't have a background in marketing, but marketing was Handy’s day job for seven years at startups. So instead of hustling on cold pitches to find new consulting clients, he spent his time writing. “I built a brand for us by writing blog posts that really resonated with a bunch of people. I had a newsletter that was read by about 6,000 people.”

- Pulling back the curtain on dbt for clients. Eventually, Fishtown began working with later-stage startup clients with more sophisticated data teams — which meant they hired technical data folks who’d know how to use dbt. The first Fishtown client to use dbt directly was mattress startup Casper. “Their data team hired us to scale their data warehouse back in 2016. We told them the way that they were doing stuff was bad and we needed to move it over to dbt. So they asked for a demo. Over the next week, we refactored all of their existing pipelines and brought them over to dbt. And they were elated,” he says.

- Setting up a Slack channel for dbt users. Once dbt had a handful of external users, between Fishtown clients like Casper and folks who’d found it on GitHub, Handy set up a Slack for the early users to trade notes. “There were maybe a dozen people in it by late 2016 who were early adopters. We were all just trying to figure out how dbt allowed us to work in new ways as a data practitioner,” he says.

A glimmer of dbt’s standalone potential

Handy recalls the moment he realized that dbt might be destined for more than just an internal side project: A prominent data leader popped up in the dbt Slack group after finding it online. (He’d go on to become one of dbt’s long-time users to this day.)

“A random person showed up in Slack and said, ‘I heard about dbt and we’ve been evaluating it for internal use.’ That person was the VP of Data Science at SeatGeek. And we were just like, ‘What?’” says Handy.

Eventually, the Slack community started to do marketing for dbt on Handy’s behalf. “One of the weirdest experiences was that people in that community who ran data teams would host meetups to try to convince other people to use dbt — so that they could hire dbt users,” says Handy. “We didn't have a designated marketing channel for dbt. Instead, people would invite us to meetups about the product that we were building.”

The pivot to software business and raising capital

Even as Handy won a steady client roster for Fishtown Analytics through his marketing and community building, dbt’s growth began to quietly outpace the consulting business. By 2017, dbt — which was still a free, open-source tool — had 100 users.

The aha moment: Enterprises come knocking

Initially, Handy just saw the uptick in dbt’s usage as a positive for the consulting business. But given his natural curiosity in data trends, he and Banin installed event tracking inside of dbt after it crossed the 100-user mark. “We pulled up the chart and realized there were now 100 companies using dbt, and we'd only worked on a consulting basis with about 20 of them,” he says.

The staggering growth rate wasn’t lost on Handy. “We threw that time series in a Google sheet and we fit a line of S, and it was very consistent, 10% month-over month-growth. When I was at Squarespace, we consistently grew at that same rate. And so I understood the value of compounding very clearly.”

By 2019, Fishtown Analytics was comprised of Handy, Banin, and three engineers. And sure enough, the line kept ticking up and to the right. The consultancy now counted SeatGeek and Casper as clients, and huge enterprises like USAA and Coca-Cola became interested in using dbt — but Fishtown had no way to support them. “They couldn't use open-source software by itself without a support contract,” he says.

Soon, dbt hit 1,000 users at a 3X year-over-year growth rate, and by late 2019, Handy realized that he faced no other option than to raise capital to continue operating sustainably. “We had three engineers supporting a thousand companies. dbt was generating literally hundreds of millions of dollars of underlying compute spend from the warehouses that it plugged into,” he says. “We had to convince ourselves to do something other than run the business the way that we had been, because it was fun.”

Unexpected team hiccups

The pivot into a venture-backed business wasn’t all smooth sailing, however. Handy says Fishtown churned about a third of the existing team over the next year.

Fishtown had steadily grown into a roughly 20-person team by early 2020. In April, Handy publicly announced the combined $12.9M Seed and Series A round, the first fundraise.

He admits he didn’t break the news in the best way. Immediately after closing the deal, the co-founders told the rest of the team at a virtual company offsite. “When I shared that news, I thought that everyone was going to be really excited. And I realized there was some weird energy in the room,” he says.

“This is probably true of any meaningful change in strategy for a business, but I underestimated the amount of work that would be needed to explain the strategy and the reasoning behind it and how different people fit into the new world. Instead, I just dropped a bomb and said, ‘Hey, isn't this exciting?’”

Despite some painful team transitions, Handy was excited to start scaling dbt’s growth.

Monetizing an open-source tool

The first order of business for Fishtown as a newly venture-backed company was making a commercial version of the beloved open-source tool. There were two phases of this next chapter as a commercial business: building a cloud offering and convincing enterprises to pay for it.

Adding a cloud platform (and engineers to build it)

Handy and the team had already been working on the cloud platform in the lead-up to the first fundraise and launched it in early 2020.

Fishtown had to funnel its limited engineering horsepower — at the time, only about five engineers — into building out functionality for the cloud. They worked on some standard enterprise-grade features, including:

- Browser-based IDE

- Orchestration

- Role-based access and control

- SSO integrations

Once Fishtown was armed with more cash, they were able to build out a double-digit engineering team over the course of 2020 to scale the cloud platform’s development.

Winning over enterprise buyers

Handy found product-market fit organically for dbt as an open-source tool mostly used by data practitioners and developers. But a few years into running a commercial business, he realized he had to build a growth curve all over again with C-suite data leaders.

“Even though we had an unbelievable amount of market pull, as we initially commercialized, it wasn’t easy for us to transform this open-source command line tool into a product that enterprises would pay a million dollars for,” says Handy.

dbt’s product-led growth set the cloud product up with a solid base of users, which shortened the time it normally takes to land enterprise customers. Within two months of closing Fishtown’s seed round, the company signed two Fortune 500 companies. But that product-led momentum couldn’t sustain the same growth curve within the enterprise for long. “Our first roughly $10 million in ARR was PLG-oriented, and so it felt like that would just continue to be true. But in data, that’s almost never true,” he says.

“When you have enough product-market fit, sometimes it allows you to get away with not being super tight on product marketing or sales motions. So around 2022, we went from this gigantic acceleration curve and overnight we realized, we have to sit at the adults’ table and figure things out real fast,” says Handy.

After the PLG flame started to fizzle, Handy turned his attention to layering on a sales-led motion for the cloud platform. “We had to focus our efforts on telling cohesive stories to senior data leaders. We had to have a very clear, explainable answer to the question, ‘Why should I use the commercial product and not the open-source product? And it had to be digestible by someone with a C in their title,” he says.

Handy’s answer: dbt Cloud can handle complex data for companies of every size.

“The longer people used dbt, the more complex their code became,” he says. “It was a problem for the most sophisticated dbt users, who were often at the largest companies. So there was a real opportunity for us to step in and solve that for them with dbt Cloud.”

To tell that story to enterprise customers, Handy relied on data, naturally. “At a user conference we presented a chart that showed the number of dbt projects that had a certain number of models in them — over 100, over 1,000, et cetera,” he says. “We watched that number climb and we knew as users ourselves, ‘Oh my God, trying to work in a dbt project with 5,000 models in it is challenging.’ So we started with that quantitative data point and asked folks in our community about their experiences with these very large, complex dbt projects, and validated that this was a pain in the ass without a cloud platform.”

One of the things about product-market fit people don't realize is that you have to keep solving for it. Constantly.

The hidden benefits of delayed fundraising

Handy operated Fishtown Analytics as a bootstrapped consultancy for nearly four years before raising any venture money. He’s now thankful that he chose this path.

“There's two superpowers you get if you come via the consulting route, and there’s plenty of costs,” says Handy. “I'm not suggesting that this is the only right answer or that it's for everybody.”

These were the pros of starting as a consultancy, in Handy’s view:

- You can keep your fingers on the technology. “I spent all of my days focused on client work up until the day we raised venture money,” says Handy. “I was deeply in the weeds of our product and the problem it was solving. I was writing code as a user would every day.”

- You can grow on your own timeline. “To unlock a venture-scale outcome, you need an exponential growth curve. And sometimes you can’t magically will those into existence.”

Sometimes you need to give yourself time to innovate, and earning revenue buys you time. And you need to stay close to customers — which a consulting business lets you do.

Looking forward

Focusing on dbt Cloud’s ability to solve data complexities has helped kickstart enterprise growth in recent years. As of 2025, the company now counts some 5,000 companies as customers and has 85% year-over-year growth in adoption among Fortune 500 companies — and blew past $100M ARR (scaling from $2M in just four years).

These numbers are a far cry from dbt’s humble beginnings as an open-source repo on GitHub. Now, Handy’s eyeing the next phase of growth for dbt Labs: data engineering powered by AI.

He’s never been one to fight the changing tides of tech, and just as he embraced the advent of the cloud, he’s excited about what AI can do for his line of work. “It will be hard to compare data engineering in 2024 and data engineering in 2028 and say ‘those are the same things,’” he wrote. dbt Labs recently rolled out some new AI tooling, including dbt Copilot, an AI assistant in dbt Cloud.

Nearly a decade into a wildly unexpected entrepreneurial path, he’s come to enjoy the ride. “The first couple of years of the venture-funded journey were extremely stressful for me. It was a big transition. But I'm having a lot of fun at my job now.”