At every step in his career, Ayr Muir made the “right” choice: MIT, Harvard Business School and McKinsey — could there be a more ideal career path? Then Ayr decided to leave his high-paying consulting job to start flipping burgers.

What Muir didn’t tell most people was his secret ambition — to build a health-conscious and environmentally-friendly fast food restaurant chain that will someday eclipse McDonalds in size. To achieve this, Ayr realized early on that his assumptions would almost always be wrong and that the only way to succeed would be to take ego out of the equation.

At our last First Round Capital Design+Startup talk, Ayr shared how his company, Clover, is creating an entirely new kind of restaurant chain, and achieving this lofty goal by thinking like designers.

Start with “Why”

In his well-known Ted Talk, Simon Sinek explains how Apple is able to motivate employees and customers by starting with the “why.” Most companies begin with the “what”: “We sell computers.” Apple begins with the “why”: “Everything we do challenges the status quo. We believe in thinking differently. We just happen to make great computers.”

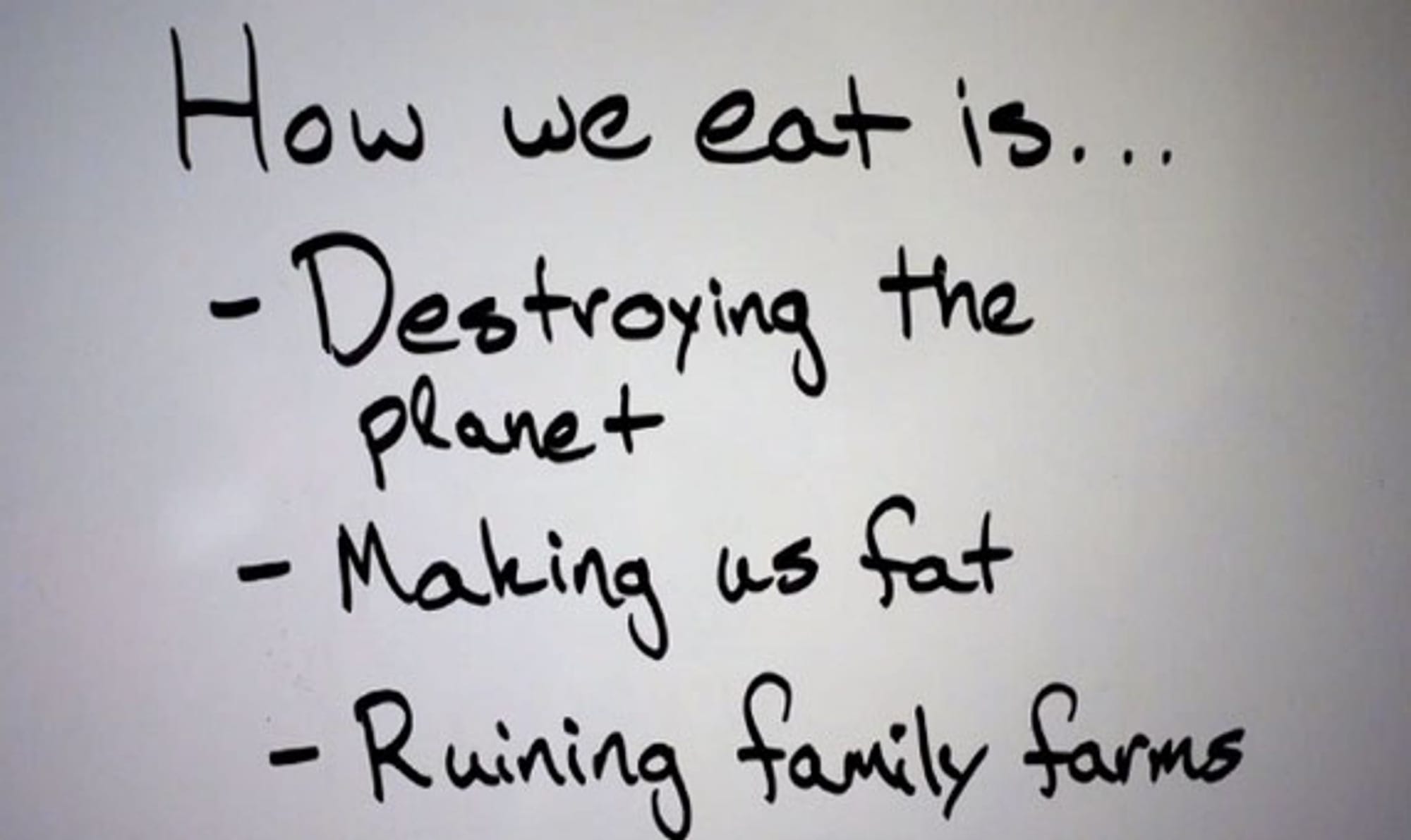

It’s this commitment to central ideals that makes a company inspiring. To this effect, Ayr began Clover with an overarching list of problems that his company would commit itself to solving.

While getting a hybrid, attacking big oil and buying fluorescent light bulbs are all the rage in combatting carbon dioxide emissions, there’s virtually nothing being done about the most glaring source of these gases: cow farts. But seriously, bovine flatulence contributes 18% more to greenhouse gases than the world’s trains, planes and automobiles put together.

What we eat is also tied closely to the obesity epidemic here in the United States. Thirty years ago, the worst US state’s obesity sat at about 14%. Today, the best state is above that rate and the worst sits above 30%. Additionally, McDonald's and its ilk have transformed corporate agriculture, destroying family farms and sustainable farming.

Those problems are the inspiration behind Clover, an entirely new kind of vegetarian restaurant built specifically for non-vegetarians. Muir has learned that the companies with the most meaningful impact almost alway begin with trying to solve a big problem.

Learn from the Best — Even at Minimum Wage

Have you ever heard that McDonalds doesn’t hire overqualified people for fear of their arrogance? Well, Ayr put that myth to the test. He had five weeks of vacation time saved up at McKinsey, so he applied to work at McDonalds. And was rejected eight times.

It wasn’t until his fourth interview at Burger King that he got the job. And the only reason he got it was because his boss assumed that “consulting” on his resume was a euphemism for “out of work.” From there, Ayr went on to Panera Bread. At both of these jobs, Ayr learned how some of the best in the industry operate at the ground floor. Most executives would pay good money for that kind of inside knowledge, but few would be willing to get paid minimum wage.

Cheap & Learn

Ayr set out to start a business that he knew almost nothing about. Sure, vegetarian restaurants existed before, but none that wanted to solve the problems he did, and none that were built for carnivores. So he set out to maximize his learning rate. He recognized that:

Failure is where you learn. We love to fail. We go out every day hoping to fail. I just hope that I don’t make the same mistake I made the day before.

His slogan of “Cheap and Learn” exemplifies this idea. You can only really learn after you’ve made a mistake. Companies often say they want their employees to take risks, but they don’t act that way. This philosophy needs to be woven into the fabric of the company. The one caveat to this mantra is that “cheapness” is used in a broad sense. While it obviously means financially cheap, a cheap experiment also shouldn’t disrupt your employees too much or ruin relationships with customers.

With this idea in mind, Ayr steered clear of outsourcing Clover’s menu or spending all of his money on focus groups. Instead, he was inspired by his favorite college food truck operator to start a food truck of his own. The idea was that Clover would be able to experiment and iterate — more rapidly and with less risk — by operating out of a food truck than a store. After Clover developed it’s irresistible menu, it shut down its food truck experiment and begin the restaurant game. However, the Clover food trucks didn’t stay away long. Customers demanded their return and today Clover is the nation’s largest operator of food trucks.

But to really maximize learning, a company should encourage all of its employees to not be afraid of failure. Once, an employee came to Ayr and shared that he wanted to try to sell cinnamon lemonade. Thinking it was a disgusting idea, Ayr gave only one piece of feedback, “Just don’t don’t make a lot.” Turns out, it was a smash hit. Clover had been making lemonades from scratch each morning before — but with more obvious ingredients, like raspberries and blueberries. "All of a sudden, this is an answer for us for winter lemonades. When we don’t have all those berries, we can use spices. It’s a tangible example that if we weren’t willing to fail, we wouldn’t have been able to learn."

Check Your Ego at the Door

Ron Johnson will go down in history as the worst possible thing that could have happened to JC Penney. His brash nationwide rollouts alienated its core customers. When questioned on these, seemingly-arrogant techniques, Johnson had the perfect response: "We didn't test at Apple.”

Unfortunately for him — and JC Penney's stakeholders — Apple was the singular exception, not the rule. Apple had an unbelievable product that would have sold a hundred different ways. All they had to do was happen upon one of them. Any non-Apple retailer knows, testing is the core tenant of retail innovation: try out something in one store and then slowly roll it out to the country.

Not even the customer knows what he wants, so how could a retailer possibly know? Nobody is that smart. The key is to recognize this fact, remove ego from the equation, and go experiment–again and again and again.

Transparency

Every successful startup eventually gets to “that awkward size where they need some good training programs in place. And, unfortunately once you need them, you needed them yesterday,” Muir says.

Clover tried something new with its training materials and employee handbook. First of all, it never finished them. Each new version just expands on the previous one, iterating and improving as it goes. Secondly, it published its Teacher’s Guide online for anyone to see. “Literally all of our customers can read it. My employees can read it. So if you're an employee, you can go and read the cheat sheet for your trainer. You can go and read the teacher's guide for the next training session you have. But why not? I mean, if they want to take extra time and learn it, that's fantastic... The cool thing is that we get feedback from customers that sometimes say ‘you misspelled whatever on page five.’ I’m not even kidding. We get these crazy, detailed comments from customers — sometimes long, multi-page things.”

“We’re able to engage in that because we’re being really transparent and open with this and we’re not scared to share something that’s a work in process. And, as a result–like the food, it's going to lots of rapid iterations. When you embrace this kind of approach, cheap and learn, cheap and learn, your evolutionary timescales shifts really dramatically. The magnitude of changes in our training program in the last six months are just massive. And it's gotten better and better and better really fast.”

Don’t Just Listen to Customers — Push Them Too

“People come by for breakfast and see us making the soup for later and they ask, ‘Oh what’s the new soup today?’ Pat, a customer who loved us early on, asked us one day and I said, ‘It’s a turnip soup.’ And Pat said, ‘Ah God, I hate turnips. I don’t even allow them in my house at Thanksgiving. Anybody brings turnips, and I tell them to leave them outside.’

I was like, ‘You know, taste it.’

‘No no no.’

‘You’re going to like it.’

‘No no no.’

We knew Pat at this point. And she came back for lunch that day and she was getting some other things and I was like, ‘Here’s a sample.’ And she refused and I said, ‘Just take a little taste. It’s not going to kill you, Pat.’ And she loved it. And she buys that and a lot of other soups since. But, you know, sometimes listening to the customers involves an interaction and an engagement. Sometimes you have to push people little bit and we've had a lot of fun success with that.”