Giving away your LEGOS has become a core tenet of scaling startups. But in practice, the act of transferring ownership is often far more painful for most founders — especially if they have a favorite child in one area of the business. Product is, understandably, one of the hardest LEGOs to hand to someone else. Maybe a founder was CPO at a previous company. Maybe they think roadmap planning is where they can add the most value. Or maybe they just have a desire to hang on to control over something that's so core to the company’s success.

That’s one reason hiring your first PM can be difficult. Another is timing. At what scale do you actually need a PM? And how’s AI changing all this?

Over the years, we’ve collected a ton of valuable advice about how to hire a PM, but less on when it makes sense to do so, especially for founders who are at the pivotal moment where they’re considering bringing on their first product manager.

So we wanted to give early-stage founders a few heuristics for this decision from someone who’s gone through the process firsthand. Saumil Mehta is Global President at Ticketmaster, but before that, he spent nearly a decade in product leadership positions at Square, which acquired the company he founded (where, for a long time, he acted as both CEO and PM).

He acknowledges there’s no one-size-fits-all answer but instead, thinks about when to hire a PM based on the signals you’re receiving from the business and the product, and where your time as a founder will have the most impact.

With that, here’s Mehta.

As an early-stage startup founder, I had two titles: CEO and, unofficially, IC PM.

Things were going great. My company, LocBox, just raised our Series A and brought on a handful of engineers. We had a sales and account management team. Our customer roster of local businesses was quickly multiplying.

But my colleagues kept nudging me to hire our first PM. Turns out I was a bottleneck for engineering and design.

I was torn. I’d spent my whole career in product up until starting my company. I felt overprotective of every single product decision. I was tight with each engineer and designer.

But the financial realities of a cash-burning startup also loomed large. Should our next incremental dollar of spend go toward a full-time engineer, designer, account executive — or do we really need a PM?

While mulling over the decision to hire the first PM, an old startup adage kept ringing through my ears: “If you’re not building, and you’re not selling, why the hell are you even here?”

This was 15 years ago, but today’s founders still wrestle with this same question. And the decision has only gotten more complicated as AI upends roles and org charts even at the smallest startups.

While there’s no one-size-fits-all answer, I developed a litmus test to help make the decision. After selling my startup to Square, I spent nearly ten years there as a General Manager and later Chief Product Officer. Now I tell every founder to use the same system I used to make the decision for my startup.

Here’s my rule of thumb: Hire your first PM once the marginal hour you spend on product work is worth less than the same hour you might spend on go-to-market or company building.

This recognizes that while founders should keep the reins of the product strategy, there comes a point when the product work in a company gets highly tactical and competes with other equally valuable work. Should you still be planning bi-weekly sprints or synthesizing go-to-market feedback and turning it into digestible artifacts that an engineer or designer can co-create? Owning every tactical PM activity is fine for the founder who can delegate away GTM or other company-building work. But time is finite and opportunity cost is real. Eventually, the equation flips.

A founder of a seed-stage AI startup told me, “The adage that founder-led sales is the fastest way to product-market fit is almost always true.” This sentiment is echoed by another founder of a Series A payments infrastructure startup: “We knew we wanted to build an industry-leading payments infrastructure for government benefits. But my own focus had to be on GTM and growing into a sales role, so I had to hire a great first PM to allow me the space to do that.”

The exact moment this happens is different for every company. I’ve worked with companies that hired their first PM months after raising their first round, while other founders stuck it out as IC PMs well into the growth stage.

Use these four simple heuristics to help you decide if you’re ready to bring on your first PM.

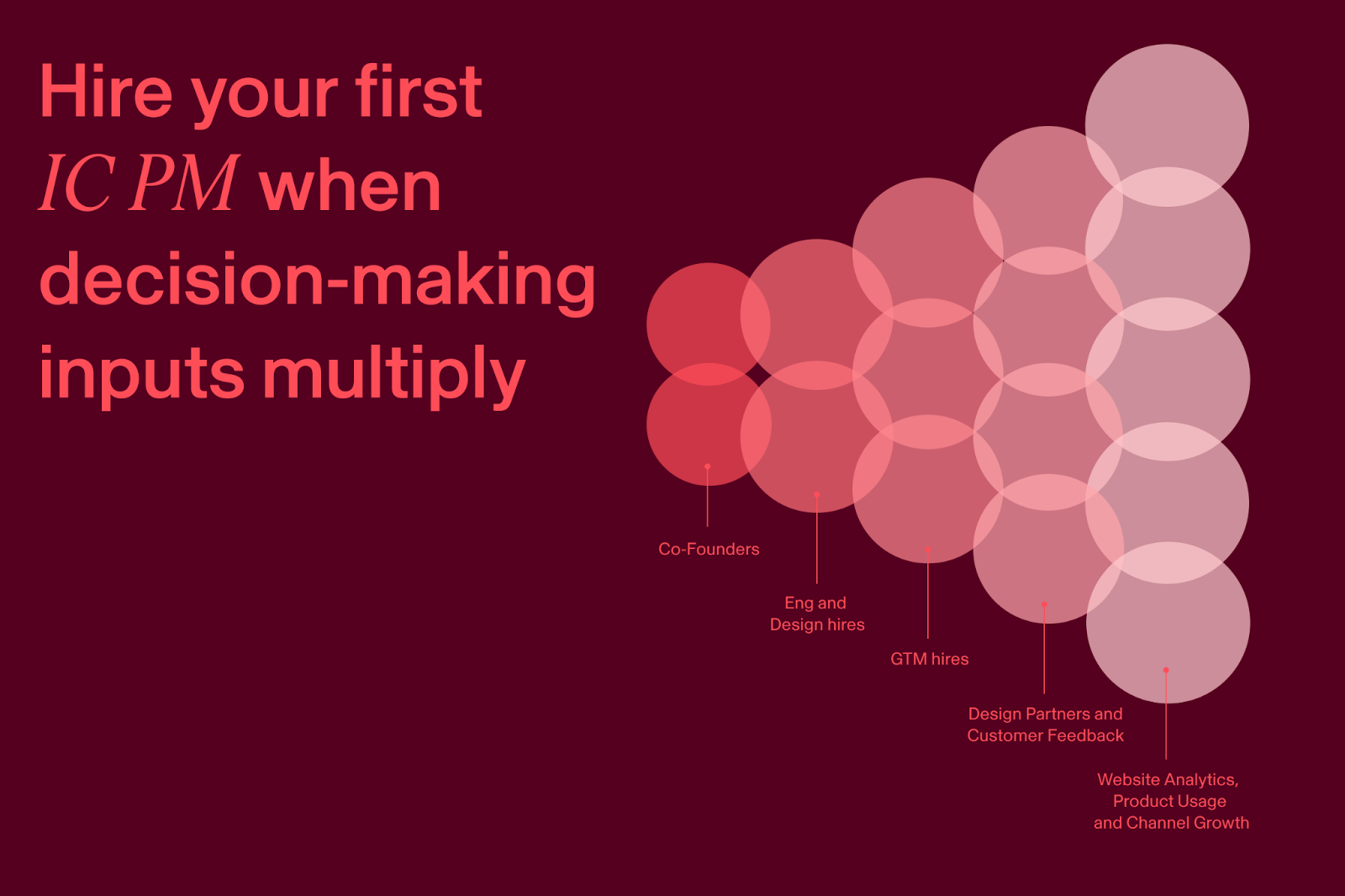

1. The rate (and frequency) of inputs for decision-making

At its core, the PM role is about making good decisions in highly uncertain circumstances. This requires signal-gathering and synthesis across multiple input sources.

On day zero of any startup, there are only two sources of input — the founders’ own hypotheses about the market, and prospective customers’ opinions about their pain points. Product-market fit is a successful marriage of the two. Unsurprisingly, at this stage, hiring a full-time PM is actually counterproductive, as it’s the founders’ job to navigate the idea maze and find PMF.

Once you clinch nascent PMF, you start building more features and upping your GTM focus. In the first three to six months, you may bring on the first few engineers, designers and business hires. Within six to nine months, you may have landed design partners to test the product and give feedback. You’ve likely gained some traction and are seeing signals across product usage and website traffic, and you’re analyzing and optimizing different channels.

So within 12-18 months, what was once just the founders themselves grows into a fast-moving startup with inputs coming from engineers, designers, prospective and current customers and analytics sources.

Even if the overall product strategy is set in stone, this step change of input volume demands rapid, tactical product decision-making. You’re confronted with decisions you never had to make before. Should you build Feature X or Feature Y first? Should you overhaul the roadmap to make your highest-paying customer happy, or build out requests from ten smaller customers? Where do you draw the line for good enough on Feature Z? Are you shipping at the right efficient frontier of quality and velocity?

I remember tackling many of these questions as the founder-PM at LocBox. We started seeing some worrisome churn patterns and wondered if the problem was our sales process, our ICP, our account management — or simply the product’s failure to get onboarded customers to use multiple features (thus reducing churn). Our product engagement analysis wasn’t strong enough because our instrumentation was subpar, which was something we deprioritized in favor of all the other product work we had to do.

And while we had shipped some features, I wondered if we shipped the right ones. Customers were clamoring for more features that were table stakes offerings from competitors. Over time, these would all get built — but for a given two-sprint window, a full-time PM (which we didn’t have at the time) would have been able to do this much faster.

I struggled to operate at the level of detail required during the exact few days the team was sprint planning. I couldn’t get into “maker mode” when we needed it most, overwhelmed by other time-sensitive tasks important to the business. At the exact same time, I was helping close a key hire, helping sales improve their prospecting data and looking for a new office space in San Francisco.

Put simply, the number of inputs and time-sensitive tasks were creating demands on my time that working more hours simply couldn’t compensate for.

But it’s not just the divergent sources of input. It’s also the rate at which input arrives.

With most consumer apps, for example, new data and feedback arrives hourly. Funnels change weekly in response to product work. New bugs and edge cases crop up weekly. Even with mid-market SaaS customers, the product may be used differently by each customer depending on their internal workflows or the number or type of seats involved.

With AI startups, there’s a new foundational model or technology development just about every week. I recently met a PM at a high-growth AI startup who ships vibe-coded apps with a UI and development layer on top of multiple foundational models. Every model update can wind up invalidating parts of the startup’s business logic because the new model may have solved deficiencies in the prior model.

Someone has to do the legwork to keep up with the breakneck rate at which new inputs arrive.

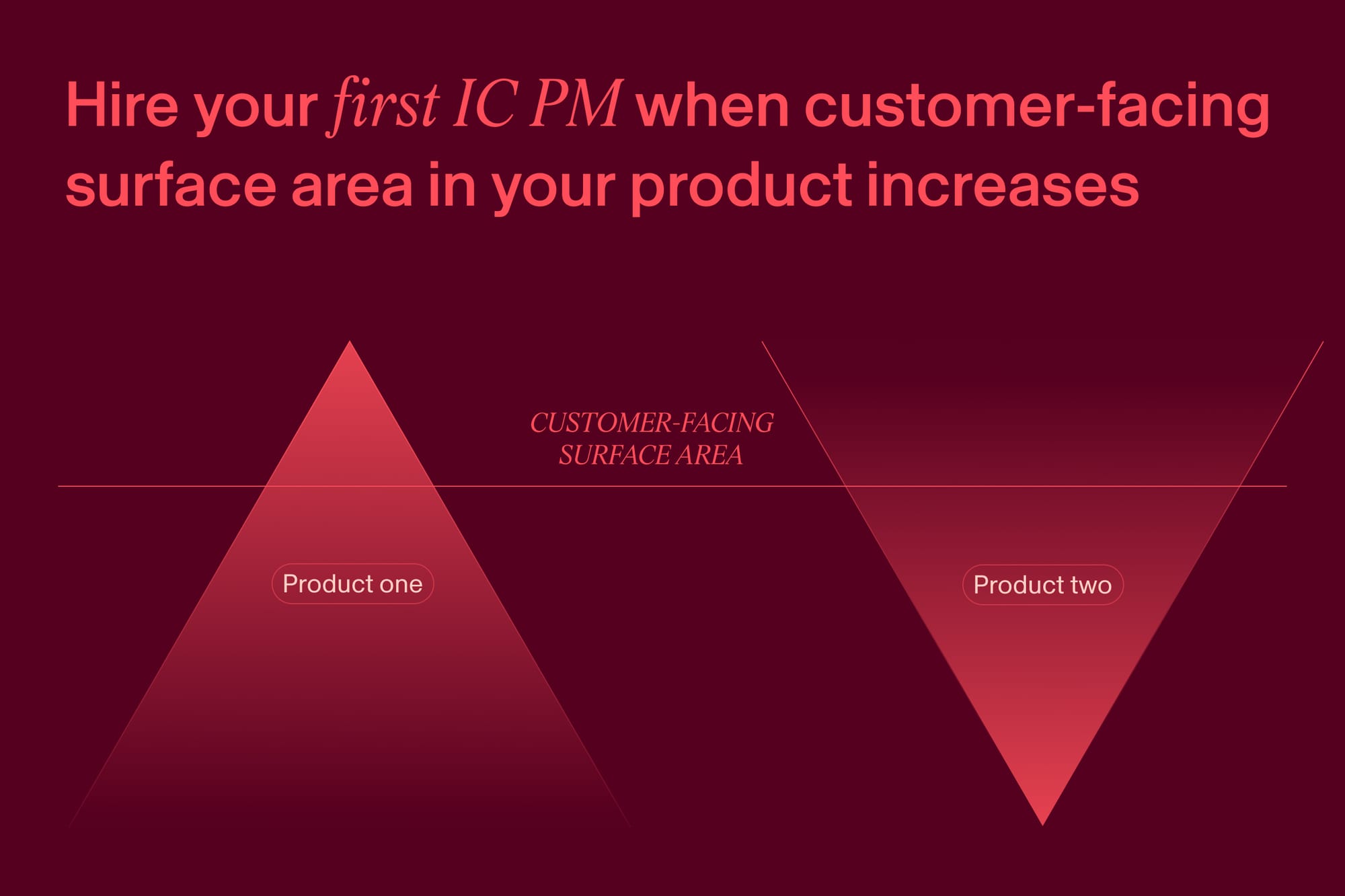

2. Customer-facing surface area

Many years ago, I was having a conversation with my then-boss at Square, Alyssa Henry, about two very different areas of Square: our payments platform that actually processes payments across the customer base and our CRM tools for small businesses that help them understand their buyers, market to them, set up loyalty programs or sell gift cards.

As you’d expect, payments was far more important to Square’s brand identity, not to mention its financial success as a newly public company. But she made a comment at the time that stuck with me: “Payments is an inch wide but a mile deep. These CRM tools are a mile wide but an inch deep. Act accordingly.”

This encapsulates the second heuristic: The need to hire the first IC PM is directly correlated with the amount of customer-facing surface area in a product.

In this case, “surface area” is an imperfect term to describe the unique number and the general complexity of the screens a customer could interact with. Got a simple web-only product with just a few screens that drive most of the customer interaction, with a ton of complexity and magic hidden behind the scenes (like the first incarnation of ChatGPT)? You can get away with far fewer PMs in general and, by extension, delay the hiring of the first one as long as possible. In June 2025, OpenAI only had ~30 PMs, even though the company had thousands of employees at that point. Conversely, if you have a product that, even in its MVP form, supports iOS, Android, web and has a ton of integrations to push and pull data — even if the level of technical complexity is far lower than an LLM — it’s plausible that you might need to bring on your first PM a lot earlier.

Why does customer-facing surface area make a difference? Because surface area is a shared space with many stakeholders with divergent opinions.

Customer-facing surface area is shared by prospects who are newly evaluating the product, current customers who are using the product or connecting the product to external data sources, salespeople who are demoing parts of the product, marketers who want to iterate on product copy, designers who sweat information architecture and interaction patterns, frontend engineers who render the designs and server engineers who work with the frontend engineers to manage business logic and data that renders on the screen. Even the sheer number of screens creates increased odds of edge cases, bugs and customer-facing product failures.

Not only are there more stakeholders, but each stakeholder has strongly held opinions about how the user experience should work based upon personal preferences (take, for example, an engineer who staunchly prefers dark mode). As a designer once told me, “Because everyone can see the design, everyone thinks they can be a designer.”

Given the number of stakeholders and their divergent opinions — there’s a need for signal-gathering and synthesis. PMs are uniquely suited to do that.

Now compare that with a product with very little surface area, like ChatGPT in November 2022, with just a handful of screens and no mobile app. The vast majority of tactical decisions in a product like this are, or certainly can be, made by engineers. And even if a PM gets involved in a platform or research team that operates deep below the surface, they have far fewer stakeholders to manage since sales, marketing, design and prospective or current customers have no real opinion about topics deep in the guts of the product.

Every startup’s surface area is different. But the following questions may help founders evaluate their own surface area and its complexity:

- Do you need multi-platform support at full feature parity (i.e. iOS, Android, desktop web, mobile web)?

- How many multi-step workflows do you plan to have? Multi-step workflows may be stateful, require conditional validation, have branching logic, demonstrate progressive disclosure — each of which is a source of complexity.

- How much of the app requires data input from customers? Surfaces that require file uploads, connecting to external data sources, real-time data validation or cleanup inherently have higher complexity than surfaces that are simply for reading text or data.

- How many third-party integrations and plugins do you need to build to drive customer value? While AI startups are using Model Context Protocol (MCP) for integration purposes, all startups need to consider the number of third-party APIs since that creates dependency on other companies (e.g. breaking changes).

- How many “roles” do you have to support in the next few months? For example, if the product surface area has to vary by the roles of owner vs. manager vs. employee, that creates higher complexity.

- How many screens in the app or site are “information dense”? These are screens with many fields, information tables, multiple charts, lists of settings and so on.

- How much of the app or website is accessible via a nested information hierarchy? A very simple app has little hierarchy — one-level navigation with one screen per nav item, for example. An app with complex surface area may have nested menus and complex hierarchy (e.g. dashboard → business management → reports → sales reports).

- Do you have or intend to implement an AI chatbot UI paradigm that executes tasks on behalf of the user? AI chatbots that are agentic require significant work tied to evals and model changes and create new complexity.

- Do you plan to be in multiple countries in the next few months?

Evaluating where the product is today or intends to be in the next few months through these questions should give founders a full picture of their surface area complexity. If the product has a lot of surface area, it may be time to consider hiring the first PM very soon.

For example, one founder of a Series A AI company building agents to resolve IT requests realized that surface area was the key factor in his decision to hire at PM: “We’re covering a lot of surface area and third party integrations, especially given our enterprise customers, likely more so than most AI startups at our stage,” he says. “So we did what felt like the counterintuitive thing and hired a PM much earlier than we expected to.”

3. The impact of AI

There’s a lot of hyperventilating about how AI will eliminate the PM role. While AI will surely impact where PMs spend their time — as is true for every type of knowledge work — I believe that the productivity boom from AI will, on balance, result in startups hiring the first PM sooner than they would have in a pre-AI world.

There are two key reasons. The first is that engineering and design productivity have changed.

The average startup feature ships much faster than five years ago, which creates a flywheel where there are more features to ship. That means there are more decisions to make, more input sources to navigate at a higher rate and more taste-making required. Once again, PMs are uniquely suited to do all of this.

As Stanford ML professor Andrew Ng put it eloquently, “Software is often written by teams that comprise Product Managers (PMs), who decide what to build (such as what features to implement for what users) and Software Developers, who write the code to build the product. Economics shows that when two goods are complements — such as cars (with internal-combustion engines) and gasoline — falling prices in one leads to higher demand for the other. As coding becomes more efficient, teams will need more product management work (as well as design work) as a fraction of the total workforce.”

This was echoed by Brandon Levey, founder and CEO at AI code compliance tool Ichi. He’s a second-time founder and also spent several years as a General Manager and Head of Platform Product at Square, resulting in an intuitive sense of engineering and PM dynamics in the pre-AI world. Historically, companies would, on average, hire one PM for every eight to ten engineers. But AI is now upending this ratio.

“Our engineers are now probably twice as productive as I’d have expected a few years ago because of AI. Our designer is now also able to double as a frontend engineer. So I’m thinking about reducing the ratio between eng and PM and adding one more PM,” says Levey.

Of course, PMs aren’t immune to AI’s impact and are expected to be more productive because of it. A lot of the rote work in the PM role — documentation, program management, status updates — will be automated away. At scale, companies may hire fewer PMs than they would have without AI. But the earliest stage startups, which are all AI-first in their development practices, will likely have to hire their first PM sooner than previous benchmarks in response to higher eng and design productivity.

In the past, a founder could reasonably wait until after they hired the first six to eight engineers. But now, if the engineers are much more productive, it may be time to hire the first PM after the first four or five engineers.

The second reason startups will hire PMs sooner is that the non-deterministic nature of LLM responses changes the actual nature of software development. This, in turn, creates new PM-like work that simply didn’t exist before. “There’s a lot more chaos in the system compared to general software being built. This added level of chaos can actually have an impact on product planning, customer research, small iterations and more, which are all important,” says Levey.

If your startup’s engineering and design is far more productive, and even more so if your startup is AI-native, your PM hiring ratios are likely lower than before.

4. The opportunity cost of your time

All startups are in a race against the clock. In this race, founder time and attention is the most valuable fuel to propel the company forward. The final heuristic relies directly on a detailed opportunity cost analysis of the founder-PM’s time.

Here is a simple but concrete analysis for the founder to consider.

- Log the time you spend on tactical product work. For two or three weeks, keep a rough daily log of tactical product work (or use a calendar tool to do so) of: in-feature decisions, biweekly sprint planning, daily or weekly product analytics and more. At the end, compute the average time spent per week. If needed, add a rough context-switching multiplier to also account for the time spent switching into and out of tactical product work.

- Track which activities you couldn’t get to. Over that same time period, write down the list of missed or incomplete tasks outside of the product that you could have taken on if you had more time available. This includes things like obtaining new design partners, selling to prospective customers or hiring. As part of this, also consider any high-priority tasks that are currently delegated to others (e.g. post-sales enablement) that might get stronger output if the founder did them. Compute a rough weekly average.

- Define the opportunity cost. Reflect on the opportunity costs of your current time prioritization. Share this analysis with close advisors or co-founders to get their input. Finally, consider these impacts:

- Which prospect deals were slowed or lost?

- Which hiring process moved more slowly or didn’t start?

- What marketing or PR opportunities did we miss out on?

- Are there any clarifications to strategic direction that we didn’t consider?

- Is there a budget or financial forecasting decision that we stalled on?

This simple three-step process will bring into sharp focus where a founder’s time is going and how the company may benefit if that time were put somewhere else. In some cases, you might run this analysis and determine it’s not time to hire a PM just yet. Or you might realize you need one yesterday. In either case, a structured opportunity cost analysis of your time can help you make a more intentional decision.