Google. Apple. Dropbox. Twitter. If anyone has had a hand in helping build phenomenal teams at powerhouse companies in their prime, it’s Kim Scott. At one point in her career, she admits she thought she was one of the best people in the world at creating amazing teams. That was, until an executive at Apple showed her how she’d been systematically undervaluing some of the most important people on her teams throughout her career. Even worse, she’d not been living in accordance with her own personal humanity.

It was a big drink of water, even for someone who has become one of the greatest champions of radical candor. Scott, co-founder of Candor, Inc., has built her career around creating bullshit-free zones where people love their work and working together. She’s seen it from every management vantage point: as a founder (Candor, Inc. and Juice Software), advisor (Dropbox, Twitter, Shyp, Qualtrics), instructor (Apple University) and operational leader (Google). So what did the Apple exec say?

Inspired by her talk at First Round’s CEO Summit, Scott shares her epiphany about management — and the mindset and framework it takes to really build a kick-ass team, starting with deciphering the distinct attributes and incentives of high-performers.

How to Tell Your Stars Apart

There’s a lot of jargon to describe superior performers on teams: 10x engineer, sales wizard, growth ninja. “Superstar” and “rock star” are also thrown about liberally, but Scott is on a mission to reclaim them —not as labels for people — but to understand what mode people are in at any given point in time. “When I spoke with the Apple executive, she was trying to convey the difference between a person in superstar mode and one in rock star mode — terms which have been appropriated and have lost meaning. But when it comes to building teams, she felt it was really important to understand their distinct roles and needs.”

Here’s what she meant:

- Superstar mode: the people on your team who are going to change everything; responsible for Schumpeterian change; a force — and source — of growth on a team.

- Rock star mode: the people on your team who don’t want their boss’ job; very talented at their role and will keep doing and digging into it for years if a boss doesn’t screw it up; a force — and source — of excellence and stability on a team.

The distinction between superstar mode and rock star mode hit a chord with Scott. “When she told me this, I started to think about dozens of people who had worked for me. There was one guy in particular, Derrick, who was the first customer support hire at a startup I led years and years ago,” says Scott. “The customers loved Derrick — they just adored him. They’d send him homemade donuts! Forget about NPS score. The real test of a great customer success person is: Do you get baked goods in the mail? This guy got baked goods galore.”

People in superstar mode want a world they can change. Those in rock star mode seek a world they can stabilize. You’ll need both.

As the company grew, Scott naturally presented Derrick with an opportunity for a leadership role. “I asked him if he wanted to head up the support team. Derrick declined. He said to me, ‘No. My real ambition is to be a Broadway actor. What I really want is to be able to leave work every day at 5pm so that I can get to these off-Broadway productions that I do.’” says Scott. “And here is where I made the mistake. I wrote Derrick off. Right at that moment, I totally wrote him off. I went out and I hired the person I thought I was supposed to hire: this super-ambitious guy, who really didn’t care at all about customer support. What he really wanted to do is be the CEO. But that’s how you build a high-performing team, right? You over-hire.”

It wasn’t long before Derrick came charging into my office. “He launched into Ayn Rand and The Fountainhead, saying that you need your architects to change the world, but you also need people to turn the lights on. For that, you need great electricians. He went on to say that you don’t want to hire a C+ architect, you want to hire an A+ electrician,” says Scott. “His analogy kind of made sense to me, but Derrick wasn’t leading the team — the other guy I had hired was, so I let him do it his way. Soon, the inevitable happened. Derrick quit, the homemade donuts stopped coming, NPS dropped and revenue followed suit.”

By not recognizing the contribution that Derrick was making to the team, Scott wasn’t building a high-performing team. “This instance made me realize that the way we tend to think about talent management gets it exactly wrong. Performance is a key factor — it’s important to distinguish excellent performance from low performance. That’s fine,” says Scott. “But often when we think about so called ‘talent planning’ — we use the word ‘potential.’ ‘Potential’ is exactly the wrong word.”

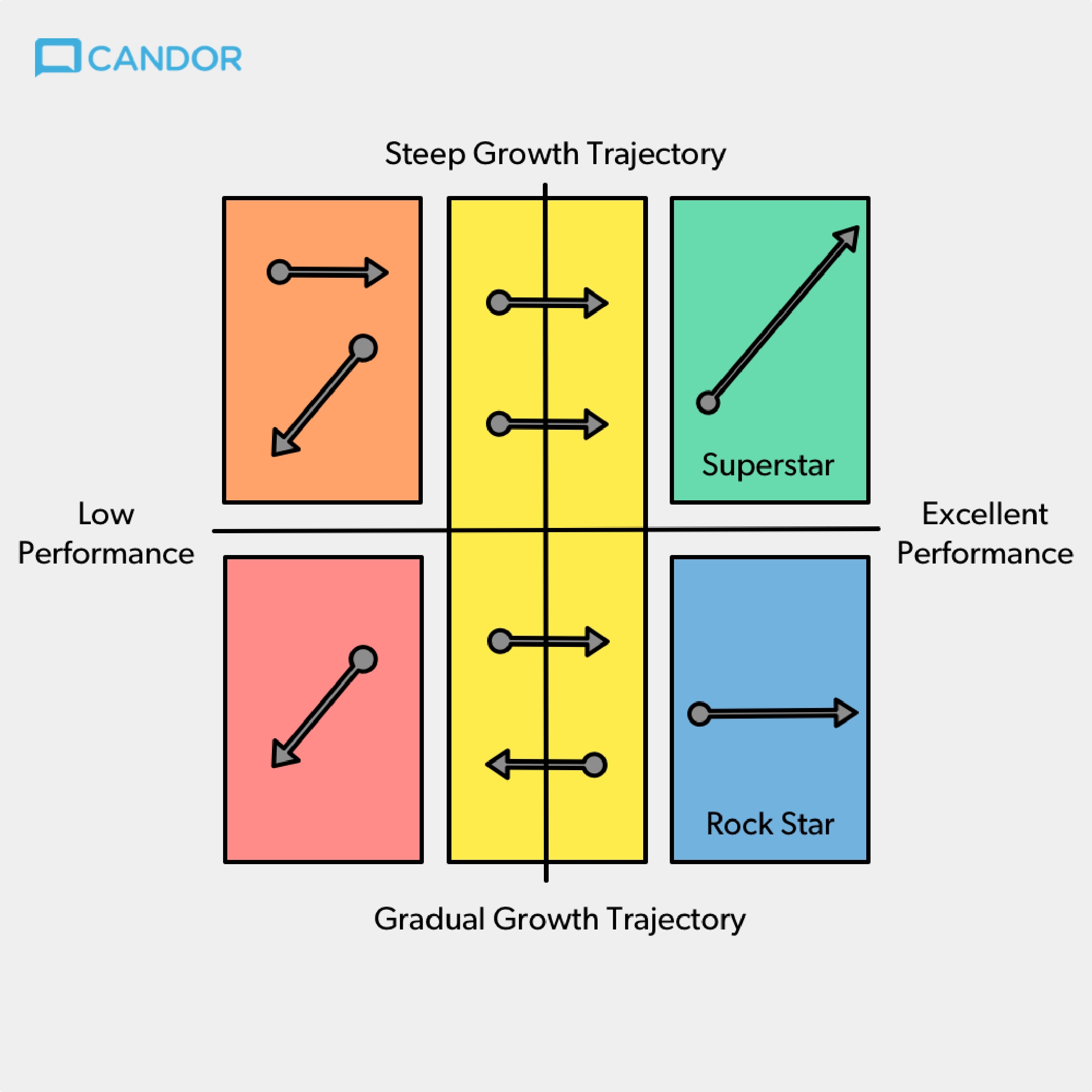

The problem with “potential” is that when you mark someone as low-potential, you devalue your rock stars off the bat. “Instead, use the word growth trajectory. There’s nothing good or bad about a steep growth trajectory or a gradual growth trajectory. It just references different phases in our career,” says Scott. “When you look at your team this way, you identify five different modes that people can be in. They can be in superstar mode. They can be in rock star mode. Or on various paths to reaching or recessing from those modes.”

Scott has seen — and been a part of — some great teams, and they aren’t all superstars and rock stars. “If you look at this chart, the majority of people on your team, of course, will be doing good work, but not great work [noted by the yellow rectangle],” says Scott. “There are always going to be those puzzling people who ought to be doing great, but aren’t [orange rectangle]. Then of course there’s the people who you ought to be firing, but you’re not [red rectangle].”

Before you start to write your team into these buckets, let this one lesson sink in: don’t use a permanent marker. “I can’t stress this enough for managers. There are no permanent markers. Don’t write people’s name in a box and leave them there,” says Scott. “Don’t use this as a label for individuals. Use this to understand what a person wants at a moment in time. Remember, these are modes, not personality labels. Use this to understand what the dreams are of the people who work for you and to help them take a step in the direction of their dreams, not your dreams. Their ambitions, not your ambitions.”

This is not your grandfather’s talent planning. It’s simple and powerful. It should be done once a year.

How To Use This Framework

Scott recommends that leaders work with their managers and teams to fill out this framework once a year. “Take the time to help every single person on your team grow in the way that they want to grow. I don’t know any leader who would disagree with that, but I know many who say they are too busy to take the time. So this is very fast,” says Scott. “Basically, all you need to do is create a shared document, get everybody who reports directly to you to put the names of their people in the box that best describes what mode they feel they’re in. Then calibrate. Then make a short, bulleted list of what you’re going to do for each person to help them grow appropriately.”

You’ll have different definitions of excellent performance, where steep growth trajectory becomes gradual growth trajectory or how these definitions apply to your company. “Use this opportunity to make sure you're all on the same page. Once everybody is calibrated, take a few minutes — and make sure everyone on your team does this — to write down some clear actions that you are going to do for each direct report. Do it for each of your direct reports, and see that they do it for each of their direct reports. And don’t mix this exercise up with performance reviews if you do performance reviews.”

The specific actions managers take for people in each of these modes not only clears the way for distinct employees to thrive, but also leaves a significant imprint on the company culture. Here’s how:

Superstar mode. For the people who are in superstar mode — those who are going to drive growth on your team — what you want to offer them is new challenges. You want to keep them learning. The last thing you want to do is squash them.

“Shortly after I joined Google, Larry Page told me a story about a time when he had a summer job and his boss gave him a project that was supposed to take him the whole summer. Larry, of course, had an idea of how he could get it done in 12 hours or less,” says Scott. “His boss said, ‘Oh no, no, no.’ He wanted to clip Larry’s wings. ‘We’re going to do it the way we’ve always done it. You have to spend the whole summer on it.’ It was a source of enormous frustration for Larry.”

When Page recounted this story to Scott, she could see how formative this moment was for him.

“Larry told me that he didn’t want anybody at Google to have that experience ever. No clipping the wings of the superstars — and that’s part of the reason why Google is such a great place to work I think,” says Scott. “They’ve done a really good job making sure that they’re helping people grow and define a path to promotion. They invest a lot in coaches. For smaller companies that maybe don’t have Google-sized budgets, it’s still possible find people who can teach your superstars new things and who are a few years ahead of them. It’s going to go a long way to help you retain them.”

Lastly, take note of the lifetime of superstars. “Make sure you identify a successor because you often can’t retain your superstars. They’re going to leave you better than they found you. Make the most of them while you get them, but don’t assume they are going to stick around forever because they often don’t,” says Scott. “Whatever you do, don’t confuse management and growth. Don’t automatically manager-track the people on a super steep growth trajectory. Often, especially for engineers, the last thing in the world they want to do is be a manager, but that doesn’t mean that they are not on a super steep growth trajectory. Make sure you’re giving the right kinds of challenges to the right people.”

Rock star mode. People in rock star mode want a pasture, not a runway. You’re not giving them a route to take off, but making space to settle into their work. What they need is freedom to do their superb work, not a path to promotion, which may distract them. “Read The Peter Principle, a management book that reminds you of something that ought to be obvious but often isn’t: don’t promote someone into a job that they aren’t good at — if they are great at doing something, don’t promote them beyond their level of competence,” says Scott.

Also, there are times in life when people don’t want a promotion. “Don’t promote people when they are in rock star mode. This advice often gets met with enormous resistance. I know it seems like a punch in the stomach or like I’m telling you to punish your rock stars. I’m not,” says Scott. “Take the case of T.S. Elliot, Nobel Prize Winning poet. Before he could make his living as a poet, he was a clerk at Lloyd’s of London. His boss famously said, ‘I see no reason why, in time — in time, mind you — Elliot might not be an assistant branch manager. But you know what? T.S. Elliot didn’t give a shit about becoming assistant branch manager at Lloyd’s of London. What he wanted — if his boss sought to retain him — was to get home an extra hour early so he had more time to write his poetry. The same was true with Derrick. He wanted his current job, not a ‘bigger’ job.”

The choice of the manager here goes beyond just one rock star’s role. “Don’t create an organization that is so obsessed by promotion and status that it feels humiliating for the rock stars to stick around,” says Scott. “Set them up as internal experts. Your rock stars love their craft and are great at it. They’re better than anybody in the company and they can help bring the people in the middle along. They can help turn good performance into excellent performance from others. If they have an interest in teaching, by all means, let them teach.”

Finally, give them respect. “Don’t do to your rock stars what I did to Derrick. What I did to Derrick was not just bad for him. And not just bad for my team and the entire company,” says Scott. “But it was also bad for me. I wish I had known that earlier, because there came a time when I was the one on a more gradual growth trajectory. In 2008, I found myself in the following condition: short, old, and pregnant with twins. It was an extremely high-risk pregnancy. Right at that moment in my career, one of the board members at Twitter visited and asked if I wanted to throw my hat in the ring to become the next CEO of Twitter.

“Now, a year before this offer, I probably would have cut off my left arm for that opportunity, but now I wasn’t so sure I wanted it. I asked my doctor for advice. She said ‘Well, just ask yourself this question: what’s more important, that job or the hearts and lungs of your children?’ Easy question to answer, right?” says Scott. “Before you attack my doctor as an anti-feminist, let me just remind you: this was a high-risk pregnancy. There are plenty of women who are pregnant with twins, who can charge ahead without missing a beat. But that wasn’t my situation.”

Scott opted to stay at Google. “I felt great about the decision that I’d made. It was obviously right for my family and my life, but even then I was still sort of ambivalent about what that decision had done for my career. It wasn’t until I learned about superstar mode and rock star mode that I understood that it had been good not only for me, but also for my team at Google. My team got better opportunities and our work did great things for Google,” says Scott. “Jumping ahead, it was also good for me, because it was while I was on bed rest when I realized how much more I cared about management than cost per click. Instead of becoming the CEO of Twitter, I coached the CEO of Twitter. It gave me time to write Radical Candor and eventually co-found a startup, Candor, Inc.”

The bottom line is that it works out, but only if you respect your rock stars — and keenly balance your need for growth with stability on your team. Early-stage and high-growth startups will over-index on superstars, but they’ll need to add in rock stars as they grow, guaranteed.

I’ve seen the wheels come off the bus more than once when teams don’t have enough rock stars. Balance growth and stability.

Middle-performance column. So what do you do for people who are just doing adequate work? “I’m going to assert that there’s no such thing as a B-player. Nobody’s capable of doing just so-so work. Everybody’s capable of doing exceptional work,” says Scott. “Never write a human being off as mediocre. First you offer them radical candor or good feedback — both praise and criticism. Give your rock stars the opportunity to teach them how to do exceptional work. Challenge those doing satisfactory work with ‘stretch projects’ that give them the chance to soar or fail. If they continue doing just adequate work, you’re going to have some hard conversations about finding them another role where they can eventually excel.”

Low performance, steep trajectory mode. Those in the upper left quadrant are people who ought to be doing great but are failing for some reason. “I call this the look-yourself-in-the-mirror quadrant. As a manager, this is when somebody else’s poor performance may just be your fault. You may have them in the wrong role. That’s the most common reason,” says Scott. “You may have given somebody too much too fast. Founders and CEOs often grow really fast in their careers and sometimes make the mistake of assuming that everybody else can do what they did. They may not be able to.”

In this scenario, ask yourself the following questions:

- Have you made expectations clear enough?

- Do you need to give these people clear feedback?

- Do they need a new manager?

These questions should get to the heart of the issue. “Sometimes people just don’t get along with their boss. Are they having a personal problem that’s temporary that you can just help them get through? Maybe it’s just a bad fit,” says Scott. “Sometimes people just are not a good fit for a company.”

Low performance, gradual growth trajectory mode. There will be people who aren’t doing well and aren’t getting better. “What about these people? It’s not nice to these individuals to ignore their low performance,” says Scott. “They are capable of doing something great somewhere and it’s profoundly unfair to them and also everyone else on your team who is doing great work if you don’t move these people along. Just do it.”

The Best Type of Manager For High-Performers

One of the biggest mistakes that managers make with the people who are doing the best on their team is just get out of their way. “They know they’ve hired talented people, and they don’t want to micromanage them. So they just step aside so the high-performers can do their thing,” says Scott. “That’s like deciding that the best way to build a good marriage is to marry the right person and then avoid spending a single second with him. It would be like my calling my husband right now and saying, ‘I’m not coming home for dinner tonight or any other night for that matter. You’re doing a great job raising those kids and I don’t want to micromanage you.’ That’s not going to go over very well with him — or our family!”

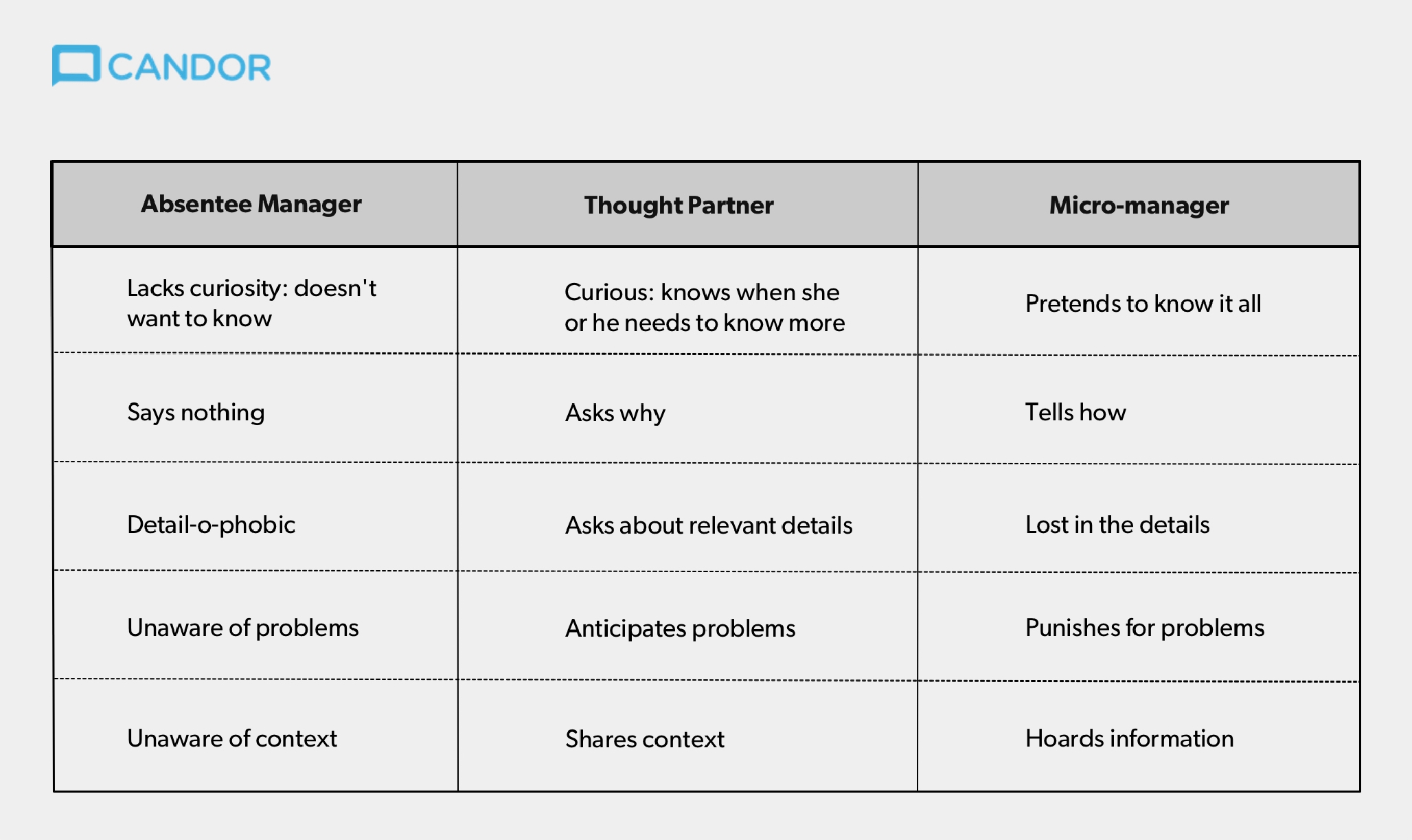

Don’t do that to the people who work for you either. They want to work for you because they want to work with you. “Keep your top performers top of mind. Literally, top of mind — as in, in your thoughts. What you want to be is a thought partner. This is not just a abstract title, like ‘thought leader.’ It means approaching their work with curiosity and with an aim to be equals in discussing it. They know when they need to know more. You are thoughtful. And you are a partner,” says Scott. “From a reporting point of view, you may still be their manager, but, for these high-performers, you help manage their curiosity, not their work.”

If you’re not a thought partner, you may easily fall into two other buckets when you manage high-performers: the absentee manager or micro-manager. “You obviously don’t want to be an absentee manager, but you also don’t want to be a micro-manager. Absentee managers lack curiosity. They really don’t want to know and the micro-manager, of course, pretends to know it all,” says Scott.

Reference this simple framework to make sure that you’re landing in the right place as a manager for your top people:

The Start of It All

Building a kickass team starts with something incredibly simple, not a big company process, but something you already know how to do: get to know people at a fundamental human level. This is one of the most important — and also the most enjoyable — parts of your job as a leader. Understanding what kind of growth trajectory each person on your team wants to be on and what motivates them at work is a concrete first step.

“All too often people undervalue taking time to understand what motivates their people and the importance of knowing their long-term dreams. Instead of really understanding each person on their team, they have unsatisfying conversations about the next promotion So they fail to come up with career action plans that give context and meaning to their work,” says Scott.

“Having three different career conversations — life story, dreams, and career action plan — is a much better course of action. It’ll help you decode who’s in superstar mode, rock star mode and — most critically — who is changing modes,” says Scott. “Taken together, these three conversations, with each person who reports directly to you, will help you balance growth and stability so your team can scale. It’ll give meaning to your work, help build the best relationships of your career, and keep the baked goods from customers coming.”

Photography by Michael George.