In Bruce Lee’s final film, his character fights his way to the top of a pagoda, vanquishing foes of different fighting styles on each floor. As he ascends, he finds opponents more challenging than the last. On the top floor, he faces the 7’2” Kareem Abdul Jabbar, whose martial arts style and prowess matches his own. Lee’s quest is to retrieve something sacred, though it’s never named.

In the world of content, Tim Urban is the Bruce Lee of long-form. In his inimitable style, he tackles the most enigmatic, entangled topics, ranging from AI to procrastination, from cryonics to picking a life partner. The Wait But Why blogger is now fighting his top-floor challenger: constitutional democracies and the culture of politics. The sacred at stake each day? Simplifying the complex for the curious — now 600K subscribers and 1M monthly unique visitors.

In this exclusive interview, Urban shares how he distills and presents complex ideas so they're rich and resonant for others: an act that every startup leader and team must master over and over again. He discusses three common types of complex ideas — and why those distinctions matter in how you unravel them. Then, Urban shares how he thinks about explaining difficult concepts to others — and how a 1-10 rating can help. Lastly, he offers tips on how to present concepts so that they’re sticky and useful for others. From editorial team of two to editorial team of two, the Review deeply admires how Wait But Why can extricate and explain. Any startup with an equally lean team can learn a lot from Urban and his approach.

Our brains want ones and zeros. But the real world is analog, gray area and about spectrums.

COMPLEXITY ITSELF IS COMPLEX

At each turn, startup founders need to learn and convey complex ideas about their company or industry to investors, their teams, customers and the public without losing them — or the nuances of the ideas. It’s not an easy task. Even tech’s most admired founder, Elon Musk, has turned to Urban to help explain the technology he’s building, how he thinks and what’s next.

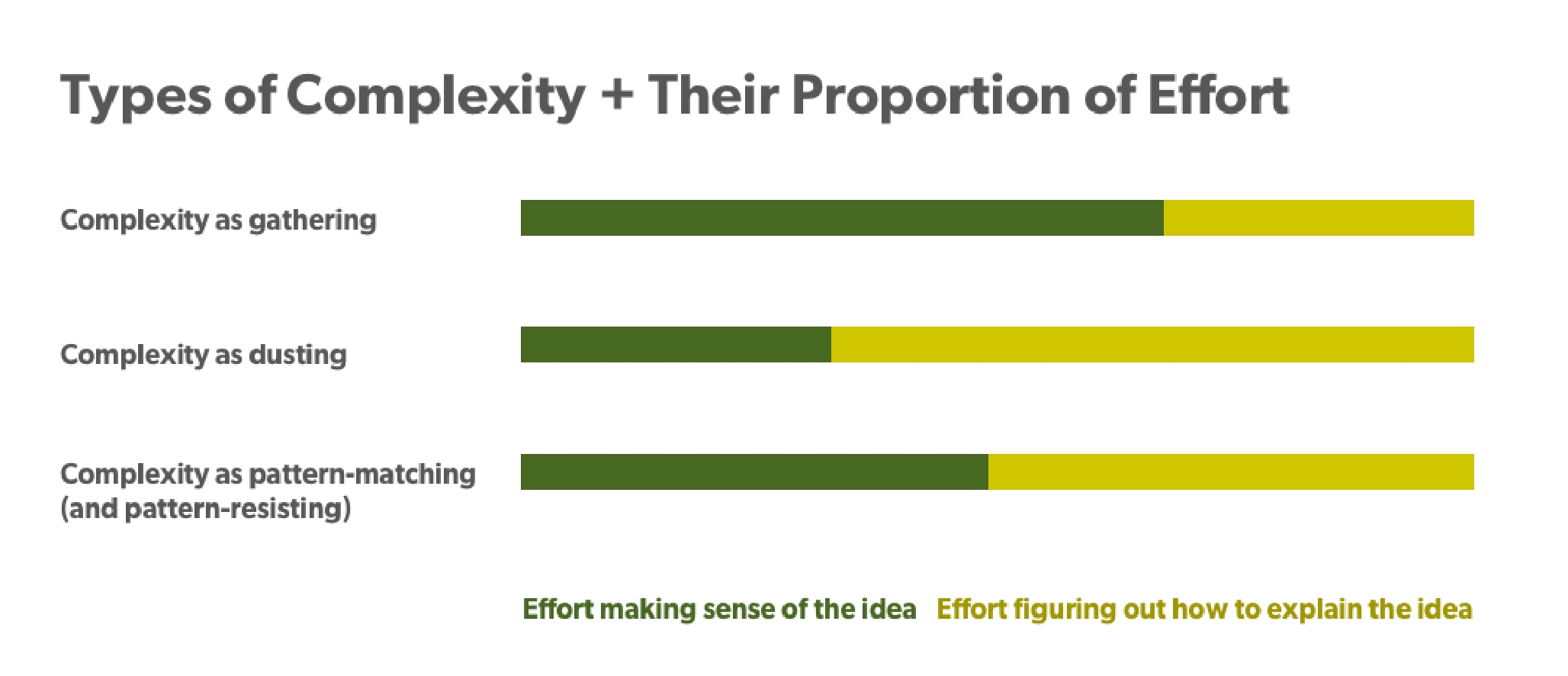

The first step is to identify what type of complexity you are attempting to unravel. Urban has observed a few main categories of complexity, each defined by the mix of actions needed to untangle it. Let’s call them: complexity as gathering, complexity as dusting and complexity as pattern-matching (or pattern-resisting). For each, there’s a different allocation of effort and time to disentangle a difficult concept.

Complexity as gathering

The first category of complexity requires a researcher’s mindset. The primary act to defray this type of complexity is collecting: the ability to amass all the material out there to make sense of it. Take Urban’s post on Neuralink, Elon Musk’s brain-machine interface development company. Though it took time to write the post, Urban spent most of his time finding material and learning. Once he gathered what he needed to understand the company and technology, it was relatively straightforward to create a narrative that was structured and easier to digest for others.

“I’m convinced that [Neuralink] somehow manages to eclipse Tesla and SpaceX in both the boldness of its engineering undertaking and the grandeur of its mission. The other two companies aim to redefine what future humans will do — Neuralink wants to redefine what future humans will be,” says Urban. “The mind-bending bigness of Neuralink’s mission, combined with the labyrinth of impossible complexity that is the human brain, made this the hardest set of concepts yet to fully wrap my head around — but it also made it the most exhilarating when, with enough time spent zoomed on both ends, it all finally clicked.”

When complexity is about gathering sufficient information to be able to digest and explain it to another, it’s a front-loaded process. The bulk of time spent is assembling and sequencing components. “To explain Neuralink, there are so many things that need to be taught. It took at least 50% of my time to find and collect that information and learn it. This is classic complexity, where you have something that takes a while to learn in order to explain,” says Urban. “Unlike something that can be explained in two minutes, it’ll take listening hard for a bunch of hours. There’s so much education that needs to happen. The goal is to put a structured package into someone’s brain so it lives in a organized way. Otherwise it’s a mess two weeks later and they can’t explain the idea.”

Complexity as dusting

The second type of complexity asks for an archaeologist's hat to be worn; it stresses detective work and determination to find something that’s buried, but ancient: an idea that is less learned and more revealed. A prime example from Wait But Why is Urban’s cook versus chef concept. In brief, chef and cook may seem like synonyms, but they’re not. A chef invents recipes; a cook follows recipes. This idea is complex in its application, as once it’s groked, the concept holds like a principle. For example, it can help explain the difference between creation and innovation.

The way that Urban landed on this analogy was very much like dusting. As he was looking into different topics, he saw the ‘cook and the chef’ concept was under the surface. And, once he found it, he asked himself: where is this concept elsewhere? And then he saw it everywhere. This type of complexity is backloaded. It takes less time to explain, and more time to get it ingrained. It’s simple on its own, but complex in how it unlocks other complex ideas.

“‘The cook and the chef’ is an unbelievably simple concept that I can explain to someone in two minutes and they understand it. So the complex part isn't that. The complex part is how you know ‘the cook and the chef’ is a first principle,” says Urban. “If you start looking for it, you’ll see the chef/cook thing happening everywhere. There are chefs and cooks in the worlds of music, art, technology, architecture, writing, business, comedy, marketing, app development, football coaching, teaching, and military strategy.”

The challenge with this type of complexity is explaining the idea in a way that people not only understand it, but how to apply it. “If you can just explain it to someone, they don't know what to do with it. They can kind of internalize it, but then forget it the next day. If you’ve explained it, you've just done step one of 20,” says Urban. “The next 19 steps are the hard part, which is getting to a place where people deeply internalize the concept in the different ways that it manifests in life — and that they have words that they can assign to it and visuals so they can really envision the concept. To me, it's getting that concept deep into someone's psyche — not just into their understanding, but into their intuition.”

Parsing complexity is like finding a fossil and realizing it’s part of a skeleton, a framework that can support life.

Complexity as pattern-matching (and pattern-resisting)

Then there’s complexity that blends a bit of the first two: it’s not front-loaded or back-loaded, but a slog throughout. The gathering of information happens throughout the learning and explaining process. You’re dusting for the simple, rich idea that’s inevitably part of a complex string of ideas. The challenging work is assigning each new bit of information to a pattern and then — and only then — deciding if that pattern should be included or resisted.

The best example of this from Urban’s writing is likely one that’s yet to come: one that he’s working on about democracy, tyranny and the culture of politics. “With something like society, it's going to take me forever because it's going to be me trying to find the pattern — the honest pattern — in a whole mess of analog complexity and uniqueness. It’s hard to do without being reckless because you can carelessly find patterns and there’s already a bunch of preset patterns set by political rules and tribes,” says Urban. “If you really look hard, you can find patterns that aren't that obvious, but that are really important to notice.”

But even once you finally find those patterns within a complicated concept like society, it’s also complex to decide how to share those observations. “If I'm explaining AI, I'm gonna have a bunch of people reading with a humble eye, saying ‘Yeah I don't understand it, I want to get it better.’ But if you're trying to explain something in politics, people don't understand it any better, but they think they do. Everyone immediately puts on their ‘uniforms,’ whether it's politics, religion, or some kind of ideology,” says Urban. “There's no humility, and there's a real delusion about your own expertise in that world.”

The Three Complexities in Summary

For those seeking to convey complex ideas to others, start by identifying how it’s complex to more efficiently simplify the concept to others. Urban has observed that it often takes him the same amount of time to disentangle a difficult idea. What’s different is the type and proportion of effort needed to crack the case — knowing that ratio can help you better tackle complex ideas.

Many topics are just straight-up complex. They’re going to take a while to figure out. Ideas that fall into these different categories of complexity often take me the same amount of time. But your goal — especially if you’re time-strapped as a founder or scrappy startup — is to have it not take longer than it should. Any of these three types of complexity require a sustained state of effort to figure out. But it’s the composition and balance of effort that’s the key.

WHO ARE YOU CUTTING THROUGH COMPLEXITY FOR?

A taxonomy of complexity is great for defining how to approach an idea — but once you have a sense of its categories, you have to be clear on how you’ll explain it to someone else.

Here are the questions to ask:

What’s the goal for you as a learner or explainer of the idea? “If I'm teaching a PhD course, I need to get to a level beyond what experts know — to a super level — so I can get people with an already advanced understanding to where they can do original work in a specific field of science,” says Urban. “With Wait But Why, that’s not my goal. My goal is to bring readers up to a level of clarity and understanding about a complex idea that they don’t need to be an expert on, but which they can be knowledgeable enough to talk about it, ask questions about it and have independent thoughts about it — whether it’s something in politics, tech or psychology.”

So what does this mean for the founder who’s trying to explain her technology to an investor? Or a hiring manager communicating his company’s emerging technology to a candidate?

Pinpoint where on a 1-10 scale the recipient of your explanation falls:

- 10 - Is world’s leading expert on the idea.

- 9 - Can ask expert questions and generate new information/data on the idea.

- 8 - Can answer expert questions and reconcile contradictory thoughts about the idea.

- 7 - Can answer any layman’s question and forms independent thoughts on the idea.

- 6 - Can answer any layman’s question and forms intelligent opinions on the idea.

- 5 - Knows about the idea, and can discern inaccurate statements about the idea.

- 4 - Knows about the idea, and can explain what’s been learned in one’s own words.

- 3 - Heard of the idea, and recites what others have said about it.

- 2 - Heard of the idea, but doesn’t know anything about it.

- 1 - Never heard of the idea.

First, find yourself on the scale before digging into a complex idea. Inspired by how Urban gives numerical rankings to levels of understanding, try this scale to rate your comprehension of a given topic. “I might start at two or three when I get into topics, and my goal is to get to a minimum of six — maybe a seven, but probably a six. Here, I can answer any layman’s question, and I have intelligent opinions, but can be humbled, too,” says Urban. “When an expert says something that contradicts what I think, I'm gonna listen hard and I'm gonna object. I’m not gonna automatically believe it, but I’m going to take it into account and maybe revise my own conclusion. I find it so fun to have a six level of understanding. Suddenly, everything you read on the topic is interesting. You can stick onto that foundation that you've built.”

The second person to plot on the scale is the recipient of the idea. For Urban, that’s his Wait But Why reader, but for you, it may be your customer. “I see the value and fun in having a level six understanding, so it’s my goal to deliver that to readers, too. I want them to join the party, to think independently about a topic with me or each other,” says Urban, who caters to the other ‘Tims” out there. “A ‘Tim’ is a certain type of person: one who really likes being a ‘six,’ but doesn't really want to be at an ‘eight.’ Look, I'm not that unique of a human. I'm very curious. I'm not an expert on stuff. I get bored if things get too technical, but I get very excited about having a fundamental understanding of something. To me, I'm never gonna run out of those people.”

Then, compare the ascent needed as a learner to the ascent needed as an explainer. In Urban’s case, his goal is to transport his Wait But Why readers to the same level he’s hit, but just faster (as will be explained later). Urban recognizes that his situation is rare in that generally his readers and he travel the ‘same distance.’ That’s not true for all ventures, but the assessment of the market opportunity is the same.

“If I start dumbing it down a little and trying to get people to a four, I'll win over a bunch of new people who aren't gonna read such a long article. The people who actually really want what I want will then get disappointed, so why would I do that?” asks Urban. “There's lots of explainer sites that try to get you from a one to a three, but the people who want to get to a six are an underserved audience in my opinion. I know that because I'm one of those people.”

The bottom line: use the scale to map your buyers’ current level of understanding to the type of knowledge they need in order to buy. Your goal is to find the the minimal viable understanding they need to take the action you want to trigger, whether that’s a purchase of a product or a vision for the future. “Take Elon. He wants to fire up the masses about something he knows they would care about if they just understood it. That's his goal with content. Not about how cool the specs are in a Tesla. But why energy, multiplanetary colonization and AI safety matters. He wants to get their heads in the right place 20 years earlier than they probably otherwise would,” says Urban. “For others who are trying to sell a new kind of nutrition, their goal might be to educate a certain target audience who they know cares about nutrition but they don't understand that they have a misconception. The goal is to clear that up. In sum, start with: Who is the audience I'm trying to reach? Where are they starting on that 1-10 scale?”

.jpg)

PRESENTING COMPLEX IDEAS TO OTHERS

It takes Urban an average of 160 hours to learn everything he needs to learn about a topic to write a post. But he knows no one is going to spend as many hours reading as he spent learning. Urban knows he’s lucky if a reader will spend two hours reading his post, so his challenge is to present complex topics in a way that readers can learn 80x faster than he did.

He prefers to describe the learning-turned-teaching process through an analogy. “The learning process for me is that I'm blindfolded. I'm feeling around trying to figure out where the trees are. The blindfold starts to come off as I start to learn more, and eventually I can see the general area,” says Urban. “Then I get in the helicopter and I start going up, and eventually I can see the whole picture. Eventually I'm in an airplane and I can see the entire picture and understand it super well, and I can see not just what the trees are, but the context around them and why they're important.”

So how can you navigate your way from blindfold to atmosphere? Gleaned from Urban’s experience, here are ways to help you better present complex ideas.

Stretch the zipline.

The shortest distance through any landscape is typically as the crow flies. Up in Urban’s helicopter, there’s greater clarity in how to most quickly get from point A to B. His post on cryonics — freezing oneself after death — is a good example. “When I started, I just had no idea. I was reading all about life extension, about cells and blood, and current medical technology. It was all a mess,” says Urban. “But by the time I was done, I realized there’s a clear throughline here, which is: the definition of death is not what you think it is. The way we define death is: when today's medical technology cannot save you. When that happens, we call you dead. But the actual definition of death of a human — if you consider a human to be their brain, personality, memories, talents and intelligence and all the other things that make them them — is just a hard drive in your head. And it's just based on the arrangement of the atoms that make up your brain. That arrangement is you, in my opinion.”

Once Urban understood that, he knew what he had to do. “I needed to change people’s conception of what death means — of the kind of core values behind life extension. I had to show that it's not vanity and narcissism any more than fighting cancer is. It's courageous. It's the spirit of loving life that makes you want life extension. I had to get rid of that stigma,” says Urban. “Second, I had to make a case for a redefinition of death. I had to define it as when the physical atoms in your brain have deteriorated to the point that arrangement is no longer not just not there, but no longer recoverable by even the most fancy future scientists. Now you’re gone and nothing can bring you back. That’s really far past the point where we consider someone dead. That person, in my definition of death, is alive. And they're right there, the arrangement of their atoms in their brain is right there for anyone to figure out — it's just sitting there, but then we let it deteriorate into something that's nonrecoverable.”

Write for the layman you were (especially if you’re now an expert).

To present these points in the post, Urban needed to stretch his line of thinking from where a reader might be who hasn’t thought about or agreed with cryonics to one who had. When he had that trajectory established, it became about sequencing the facts: from the science behind cryonics to what it means to die to what happens to your body, to what death may mean in the future. “So I'm gonna go chronologically and explain these things — and so 80% of what I learned at that point got cut out of the post because it just wasn't relevant. All the paper research on Alzheimer's or strokes. It helped me understand stuff a little bit, but it wasn’t critical. So after four weeks of research, I had packaged it into something that was tight. I could basically use my own hindsight and say, this took 150 hours, but if I could do it in two hours over, here's what I would need to learn.”

Of course you're a layman. It doesn't matter how smart you are. Everyone in the world is a layman at most stuff.

When Urban writes his posts, he appears to be in a special limbo: both wanting to understand any layman’s question while retaining the ability to remember what it’s like to be a layman. This is the key not only to humility, but to being able to orient any reader within a complex topic. “For something like AI, a lot of articles start with an assumption that I already know what AI is — and I actually didn't. I always felt like that shut part of my brain off right away as I read. I never felt oriented,” says Urban. “For cryonics, I knew that right away. I felt skeptical. And it seemed like it was both impossible and kind of ridiculous. So for AI, I want to start and build that initial definition of AI — and distinguish it from robots and what the movies make us think AI is.”

If you read Wait But Why, you see that he signals to readers — subtly or overtly — when he doesn’t know something. He tries to explain it immediately and address any other early confusion points. That gets readers’ guards down, so they trust his orientation. Your goal is to get by that wall of skepticism — the belief that the piece wasn’t written for them.

Make points viscerally — not just visually.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. But Urban uses both images and an ambitious word count, so his visuals need to achieve something more. Here are his reasons for choosing the types of illustrations he does — and tips for how to use graphics to great effect.

Ground the fireworks. Visual simplicity is critical to Urban. “A lot of times, I look at a visual and there's some fancy looking computer graphics, but the actual information in it is lacking. If you stripped out all the graphics and you put the actual information in a simple Excel table, you realize that there's not really that much information there,” says Urban. “When you dress up all these empty graphics to put out a beautiful infographic, that's the wrong thing to focus on.”

As an experiment, pull out all the numbers from a graphic and put it in a spreadsheet. Now compare the fancy graphic to the chart and ask yourself:

- Is it well-worded or a bit redundant?

- Is it an elegant capture of the data, or presenting or masking partial data?

- Does it properly categorize or erroneously conflate points?

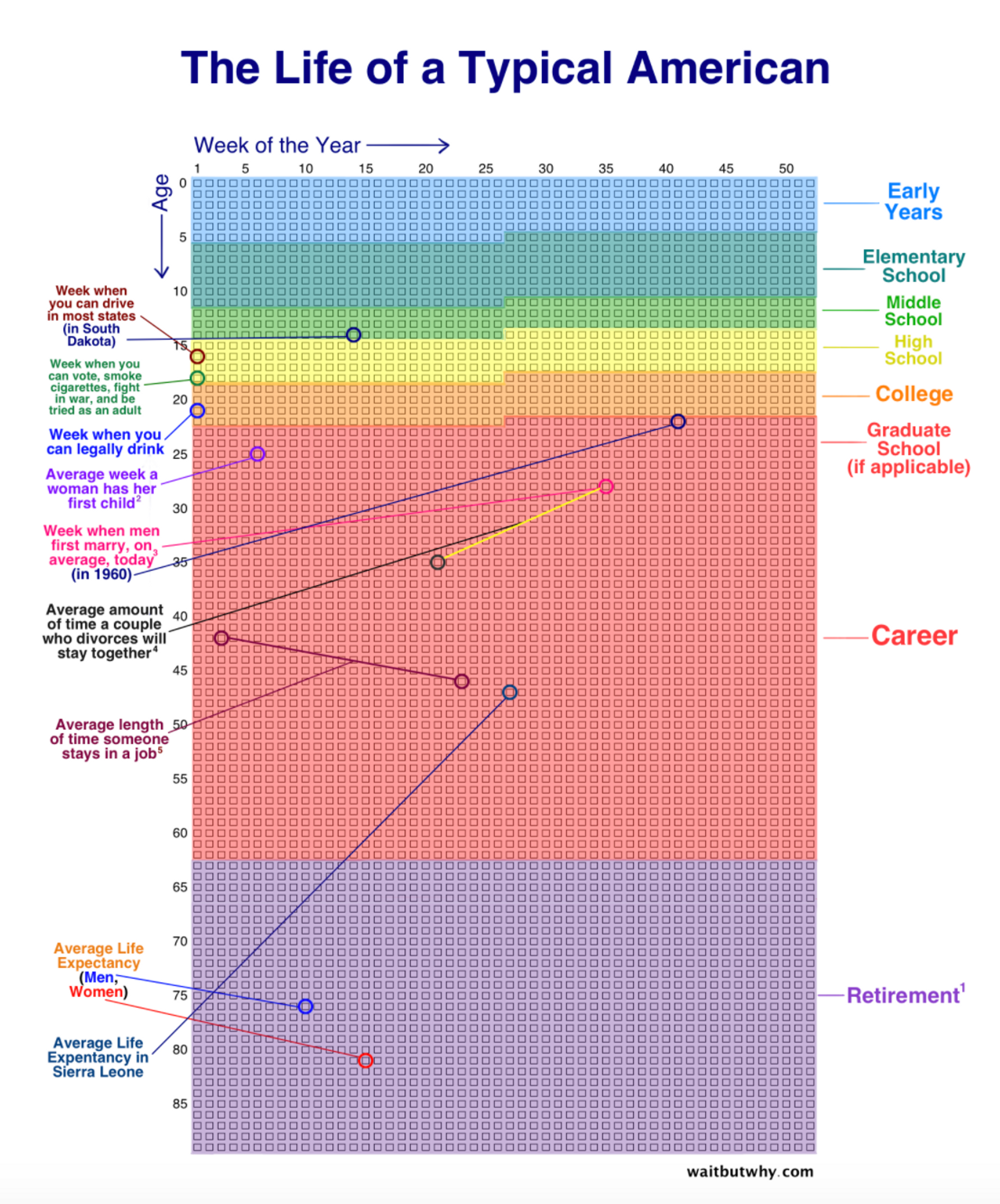

These questions can help show you if a graphic is augmenting a complex idea. A perfect illustration of this is Urban’s blocks of time post. In this case, the visual layout of the data was just a bunch of blocks, but the distance between them really made the point. A paragraph would have been much harder for most people to absorb the magnitude of the idea.

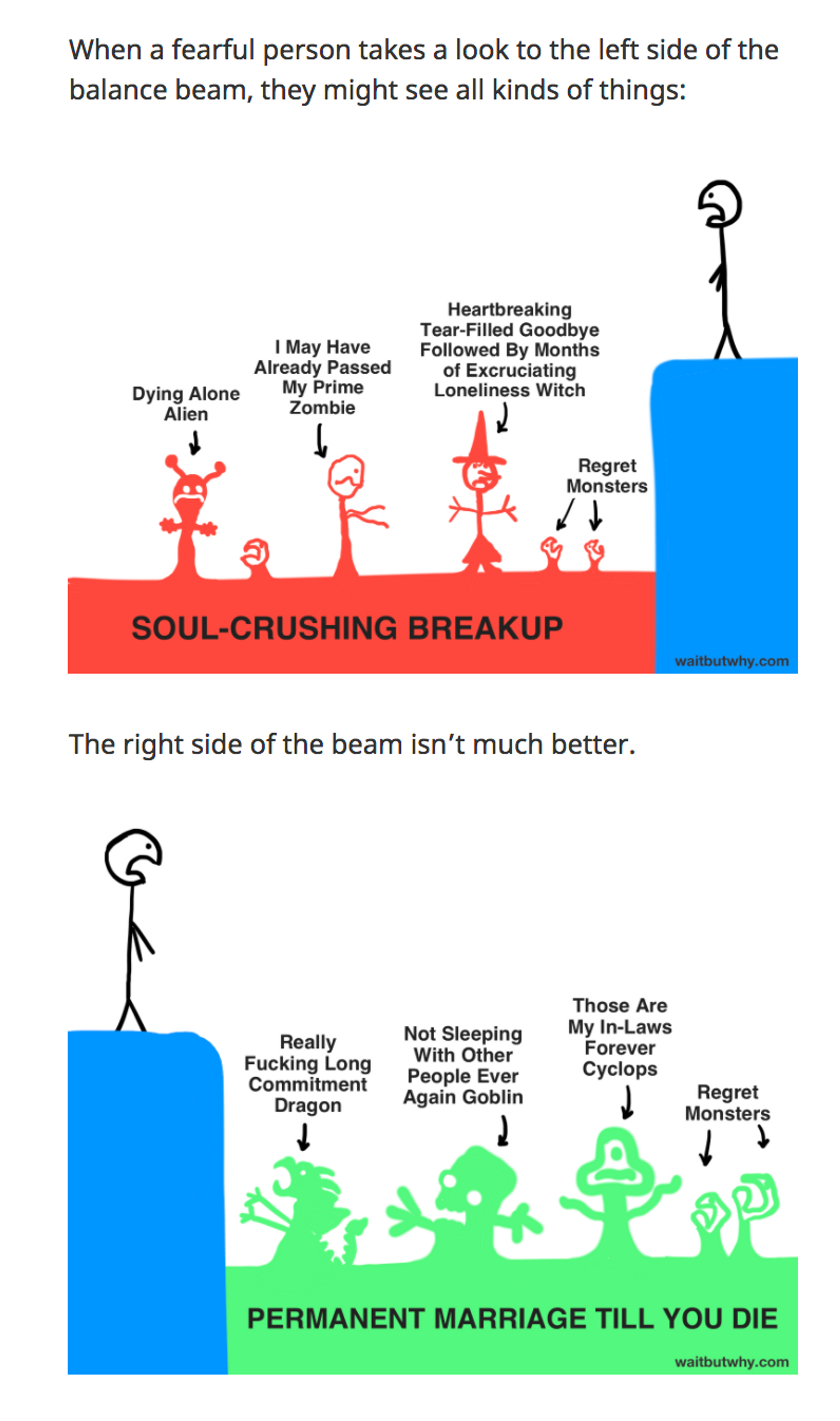

Often just a simple hand-drawn arrow seems like a teacher in a classroom teaching you something versus flash-bang marketing material. “I don't try to pretend to do fancy, well-produced visuals. I do it like I’d teach a friend if I had a napkin at a restaurant. Good tutors are not coming in with a bunch of marketing things; they're drawing with different colors and simple lines on a whiteboard,” says Urban. “So I try to do that for explanations. A lot of the times, you're trying to capture a complex psychological concept or whatever it is and there's characters involved in which case I'm going to create funny drawings. I'm going to create stick figure people or stick figure animals because to me if you can delight people a little bit, if they smile or they're laughing while they're looking at that, it's gonna stick a lot better. It just is.”

Bust a gut. You don’t need to be the Dave Chapelle of data, but find the edge of humor in your story. That’s often where you can accelerate an explanation or make it resonate. “Think about your favorite funny TV show that you haven't seen in ten years. You can probably recite 20 lines from it and tell me about all the different episodes. When something delights you, it's with suspense or humor. Your brain locks in because it's being delighted and it's gonna replay the funny or riveting moments again and again. If it feels like work to your brain, it's not gonna remember it. I'm sure some people check out when they get to a silly diagram and that's fine. That's not for everyone, but for me I'm gonna learn and remember it better that way.”

Pick the protagonist that gets you to the end.

For Urban, the hardest part can be choosing the character that will carry forth his point — with the right balance of gravity and hilarity. Sometimes that’s an anonymous stick figure. Other times it’s him. But selecting a messenger to deliver the story is often the hardest part. Here are some of the questions that can help you find your narrator:

- Who is taking the reader by the hand?

- Is it me or a a storytelling character?

- Is the narrator behind the scenes?

- Where can/should they start?

- What's the game you're playing?

- What voice are you using? Which emotions?

- Is their job to show or to tell?

There’s not one answer — and Urban admits that it’s the challenge of presenting a complex idea. “Honestly, I'm not good at this. That's why it takes me forever. It's not something that just comes to me,” says Urban. “I sit there and I toil for sometimes weeks trying to get a structure that fits. I don't want it to be just be functional. I want it to get all of the information across in a structured way.”

To show different approaches to topics, Urban juxtaposes his procrastination, cryonics and SpaceX posts. “So with procrastination, there are core forces that battle against each other in my head. So rather than describe the psychology and the structures of the brain where they come from, let's make it what they really are: very memorable and funny characters that’s way better than just explaining the psychology of something — and way more fun to read and memorable. There’s the instant gratification monkey or the panic monster. Their names were descriptives and they were drawn with humor so readers remembered them,” says Urban. “But with cryonics, there's no characters. I could have said, ‘Here's Joe. Joe wants to live this long.’ But that cuteness would have gotten in the way of the job: the conception of death. You don't need Joe; he’s a distraction, I just need to look the reader in the eye, talk to them, and explain some shit. With SpaceX, there was a lot to talk about so I need to get people to buy in at the very beginning by giving them a hint where we’re going because some people will drop off because it’s too long. But people will start to get hooked if they understand the arc of the story — and that it’s gonna be really fun at the end.”

Great narrators are comprehensive symbols. To remember them is to recall the entire concept. But if they don’t represent the full notion, the narrator loses part of the idea. And then you’ll lose part of your audience.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER

When thinking of an idea that’s hard to understand, it’s tempting to think of complexity in a singular way. Instead consider it in three distinct forms: complexity as gathering, complexity as dusting, and complexity as pattern-matching (and pattern-resisting). Each type of complexity is defined by the act most needed to unravel it. Next, on a scale from oblivious (1) to leading expert (10), map your intended starting and ending point for both your audience and yourself. Very rarely must you take someone from 1 to 10, but it’ll benefit you to know — and own — the segment of the journey that you take your reader. Lastly, when presenting a complex topic, adhere to a few rules of thumb: pass on the bell and whistles, delight through levity, and pick a protagonist like a racehorse: one that’ll get you to the end.

“People who try to explain, package and present complex ideas need to put in the work beforehand. They need to learn enough that they can get to the level where they can independently think to really wrap their own head around it, before they're ready to be an effective explainer,” says Urban. “I think these early processes should happen before any word is written or drawing is drawn. Wrapping your own brain around it and then conceiving how to present it, that's 80% of the work. People probably spend only 10% of the work doing those two things and most of the time they sit there and execute. That's not the way to do it.”

Drawings by Tim Urban of Wait But Why.