Not many people would leave a role at a prestigious venture capital firm to teach themselves how to code and “make a bunch of things no one’s ever heard of.” But not many people are like Christina Cacioppo.

“If you tell someone you’re going back to school, they get it; if you tell them you quit your job to code, they’ll think you’re insane,” she wrote in a blog post two years after resigning from the investment team at Union Square Ventures.

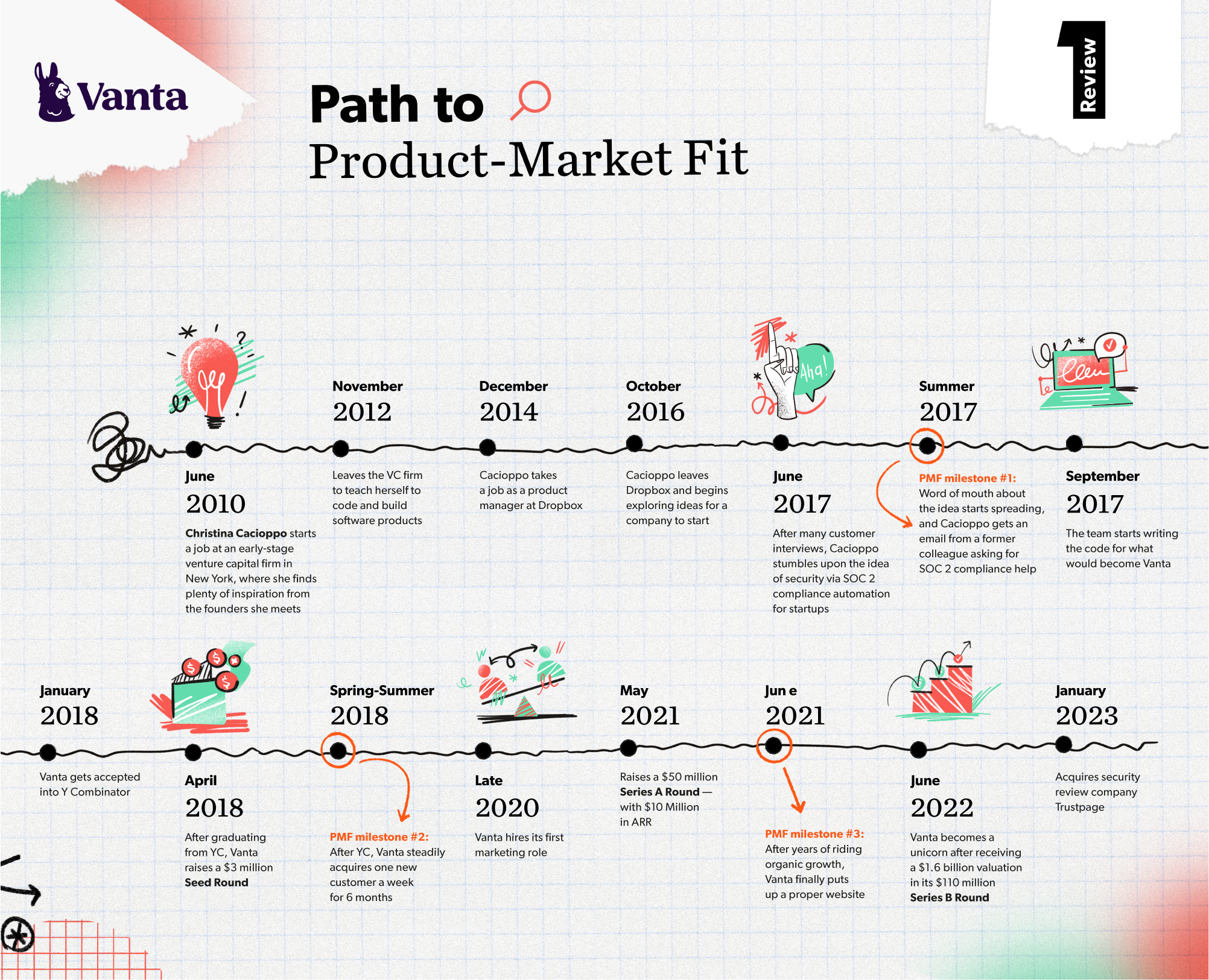

Now, she’s the co-founder and CEO of Vanta, a security and compliance automation platform valued at $1.6 billion and recently named to the Cloud 100 list. And as her story suggests, she’s never been one for following norms. She taught herself to code instead of getting a CS degree or leaving it to a software engineer co-founder; she waited until Vanta reached $10 million in ARR before raising a Series A instead of adhering to the convention of doing so once you hit $1 million ARR; and to get her first 600 customers, she relied on word-of-mouth instead of hiring a marketing team or even launching a real website.

That sort of gutsy, scrappy approach to building a business has served Cacioppo well, but that doesn’t mean her path to product-market fit was easy. Before she built Vanta, she built a lot of other things she laughs about now (it turns out a voice app for biologists isn’t a billion-dollar business).

But first, we’ll turn the clock back 13 years, to Cacioppo’s first job out of college, when the desire to become a founder first took root—though she herself could hardly admit to it at the time.

EXPLORING IDEAS

It was June 2010, and Cacioppo had just started a job at New York-based early-stage VC Union Square Ventures, where she spent her days meeting with innovative founders and evaluating companies.

“Going into my VC job, there was a part of me that did want to start a company one day, but I definitely didn't say that out loud or even in my head. It seemed like I wasn't the sort of person who started a company—whatever that meant,” says Cacioppo.

Eventually, as she witnessed the wide variety of founders who passed through USV’s doors, her confidence in becoming a founder herself started to bubble up.

“I got to the point where I said, ‘I do want to go start a company.’ But I wanted it to be a software company, and I didn’t know how to code. And I knew a lot of non-programmers started companies, but I didn’t want to go that route. So I resigned, took my bonus and taught myself to code and build products,” she says.

For two years, she tinkered with software projects. She built a book tracking website, a video messaging app for Android and a startup job board, just to name a few. But there was a missing piece. “I learned how to make things on my own, which was great, but I'd never worked at a real company building and shipping products before,” she says.

So she ended up joining Dropbox as a product manager and worked on bringing Dropbox Paper to market. Seeing the inner workings of a successful company was a crucial education for this aspiring founder, but after two years at Dropbox, Cacioppo was eager to strike out on her own.

“I’d learned a lot, and I was getting impatient. It was time to see if I had what it took to be a founder,” she says. All that she needed now was an idea of what to build. To kick off her exploration, she asked two questions:

- What new technologies are opening up novel opportunities right now?

- What do I know more about than others?

By now, it was late 2016. Amazon had launched Alexa to great fanfare two years prior, and the number of babies named after the AI voice assistant had recently peaked. In other words, the voice assistant market had reached a fever pitch.

“Voice was new and opening stuff up, and I had just gotten an Alexa device and thought it was cool,” Cacioppo says. “I also knew some things about team collaboration after a couple of years at Dropbox. So I figured I’d merge the two and build a voice assistant for work.”

This sent her down a rabbit hole of what she admits now were “terrible ideas.”

First, there was the meeting recorder that automatically transcribed all meetings across a company. “It sounds neat, and some people really wanted it, but the average person doesn't want that product at all,” says Cacioppo. “Plus, at the time, the technology just wasn't that good.” Next was a microphone that transcribed notes into Slack. “It mostly dumped nonsense into a Slack channel; it wasn't even usable.”

When her products failed to gain traction with startups, Cacioppo switched gears and honed in on a novel use case: a voice assistant for biologists working in a lab. There were a number of reasons for why it made sense at the time. “They're doing things with their hands, they have gloves, they’re working with chemicals. Imagine trying to type out notes while you’re cooking a complicated meal,” she explains.

So she found a lab, shipped them a microphone, and even built them an iPad app. “They were thrilled because no one makes software for biologists in labs,” she says. “But the market for this was the size of my thumb and I didn't even know anything about biologists. It’s funny to talk about now, but it was a true low point at the time.”

With failed idea after failed idea piling up, Cacioppo reevaluated her approach and realized her mistake.

It was a bit like the children’s book “Are You My Mother?” We had built this tool and then walked around to people asking, “Do you want our tool? Do you want our tool? What about you?” And the answer was no—no one wanted our tool.

Zeroing in on the Right Problem to Pursue

After that lightbulb moment, she drastically shifted her strategy:

- No more building. Just talk to customers. “We decided we weren’t allowed to build anything at all. We had to just talk to people—and talk to them until we had a lot of confidence and a mental model of customers, their jobs, the problems they might have and how we might solve them.” (For more here, check out Cacioppo’s write-up on some of her essential advice for talking to customers.)

- Ask them about their daily routine. “To find a good problem to solve, we really focused on what the customer’s day-to-day was like.” Cacioppo’s advice here is to get into the tangibles. “For discovery, the best thing we did was ask people to pull up their calendar. Then, we’d say, ‘Look at all the meetings you had in the past couple of weeks. What were the best parts of those past weeks? What were the worst parts? That finally got us to a problem worth solving.”

- You’ll know you understand the problem when you can predict 75% of what a customer tells you. “We needed a heuristic around, ‘When do we know we understand the customer problem enough?’ So we decided we had to keep having these conversations until three-quarters of it was stuff we already knew.”

The easy part is writing code. The hard part is building something people want. So focus first on finding the thing people want.

The initial glimmer of what would become Vanta appeared in one of the first conversations Cacioppo had, with the Product Security Lead at Dropbox.

“What he told me when we looked at his calendar was, ‘The best parts of my week are when I get to work with product teams on security issues. I get to work with the PM and the engineers and get the right stuff prioritized and fixed. The worst part is when I have to pull together reporting on the things I've done to show my manager or executives, or get on the phone with customers and explain what security we do in basic terms,’” Cacioppo recalls. “This person fundamentally liked their job, but there was this ‘work about work’ component of demonstrating that they’d secured things, and that part was tedious and annoying to do.”

Compliance kept coming up in other customer discovery conversations — but it’s a broad space. To further narrow down an idea, Cacioppo kept the conversation going by approaching startup founders, security teams, engineering leaders and sales teams and asking, “What are you doing for security at your startup?”

“And what happened was they’d generally look up quite guiltily and say, ‘Not that much, and I wish it were better.’ And I’d say, ‘Totally cool, but why don't you do more? It sounds like you want to do more, so what’s going on?’”

Sorting through these answers, Cacioppo pieced together a theme: It was a matter of prioritization. Startups were stuck between two choices: Option A was that they could spend time and energy ensuring security (which they recognized would be a good thing), but the only way they could measure the worthiness of such a pursuit was the absence of a security breach, which wasn’t a compelling enough metric. On top of that, for small startups, their biggest problem was that no one knew them, meaning it was highly unlikely anyone was trying to hack them in the first place.

Option B was that these startups could spend their precious time and energy building product features their customers wanted, which would get their business to its first revenue, and prioritize security later — when they had more time and resources.

Given the options, which one do you think these startups were choosing? The latter. Every time.

“We heard that a bunch, and initially, that was discouraging because we were like, ‘Oh, this is why there aren't security companies for startups.’ Because even if it's a good idea or it's an easy-to-use product, you're still running up against this prioritization hurdle,” she says.

But then, Cacioppo met a small startup that broke the mold.

The Aha Moment

“There was this transformative moment when I walked into Figma, which at the time was probably 30 people, and I was talking to one of their infrastructure engineers and expecting to have the same conversation I’d had so many times before,” says Cacioppo. “But this time, when I asked, ‘What do you all do for security?’ this person listed about 12 tools and a bunch of best practices and just kept going. That floored me. I was like, ‘Why? Who are you and why?’”

Figma had just signed one of the largest public technology companies, a massive deal for anyone, let alone a 30-person startup. And as part of the sales process, that public company sent over a long questionnaire to assess Figma’s security practices. Figma’s answers were mostly no's, but the team didn't want to say that. Instead, they turned the questionnaire into their product roadmap and built everything on it so they could honestly say “yes” to every item on the checklist.

A lightbulb went off for Cacioppo. Figma had successfully aligned securing its company with growing its business. Out of necessity to close a big deal, security became the top priority. That meant if she could help these startups prove their security practices (and in turn, help them sell to bigger companies), she could create a product that generated real value.

That led her down another rabbit hole of figuring out how she and her team could productize this idea. Could they standardize the kind of questionnaire that the public company had sent Figma? Could they create a way to automatically answer it?

“We couldn’t do either of those things because the questionnaires were just so bespoke and custom,” she says. “That’s when we realized the real question we needed to be asking was, ‘How can we make it so startups don’t need to get a questionnaire?’”

The answer was — with a compliance certification like SOC 2. SOC 2 is a framework that establishes a set of security and compliance guidelines that serve as a gold standard for how a company manages and protects customer data.

For SaaS companies, obtaining SOC 2 certification is paramount if they want to capture enterprise customers because these large companies must ensure customer data is in good hands. SOC 2 provides that proof.

“Practically speaking, a SOC 2 is an 80-page PDF that lists the security practices of an organization. It essentially says, ‘Hey, as a company, we have these practices, and an auditor has come into the company and made sure we do what we say and written some details on how we do it,’” Cacioppo explains. It’s an incredibly time-consuming process, which is why practically zero startups had SOC 2s.

It seemed like they’d found their winning product idea: Just automate the process of getting a SOC 2, and startups would be banging down their door. But, not so fast.

When we went and talked to consultants and auditors about automating SOC 2s, they were like, “Well, you can't do that because every report is unique.”

Cacioppo and her team pushed back. Sure, historically, these reports were unique, but did they have to be? Even if one business is different from another, should the way that they protect their customer data be wildly different?

“If we're talking about security practices, yeah, there's some nuance, but there's also best practices,” says Cacioppo. And that common ground is where she decided to build the first MVP.

BUILDING THE MVP

Cacioppo had her heart set on starting a SaaS company, but before Vanta became software-as-a-service, it was a service without software. Before they wrote a line of code, Cacioppo and her team became SOC 2 consultants.

In their first experiment, they went to Segment, a customer data platform, and interviewed its team to determine what the company’s SOC 2 should look like and how far away it was from getting it.

“We made them a gap assessment in a spreadsheet that was very custom to them and they could plan a roadmap against it if they wanted,” she says.

Cacioppo was running a test to answer two key questions:

- Could her team deliver something that was credible?

- Would Segment think that it was credible?

The answer to both questions ended up being “yes.” And thus, the first (low-tech) version of Vanta was born—as a spreadsheet. “It actually went quite well, so we moved on to a second company, a customer operations platform called Front,” she says.

For this experiment, Cacioppo wanted to test a new hypothesis: Could she give Front Segment’s gap assessment but not tell them it was Segment’s? Would they notice?

“We used the same controls, the same rules and best practices, and still interviewed the Front team to see where Front was in their SOC 2 journey, so it was customized in that sense,” she says. “But this test was pushing on the 'Can we productize it? Can we standardize this set of things?' And most importantly, ‘Can they tell this spreadsheet was initially made for another company?’”

They couldn’t. And then, Cacioppo got an email that sealed the deal in terms of validating her idea.

A former Dropbox coworker sent a pretty great email, which was basically a version of, “Hey, I hear you've become SOC 2 consultants. That's super strange. We should get a drink because, like, what are you doing with your lives? And also, can you come get a SOC 2 for my company as well?”

“That was the final piece I needed to pursue the idea for SOC 2 compliance automation,” Cacioppo says. “We had this gap assessment spreadsheet that had been useful for three startups, and word of mouth was spreading. Now we could start coding and actually building a software product.”

Keeping things scrappy, the first software version of Vanta had very little software to it. It was a simple form where customers entered their AWS credentials and, behind the scenes, the team manually pulled the information and Cacioppo personally wrote the reports. “We told customers that the software was a little slow, so we’d send the report the following day,” she admits.

Y COMBINATOR AND EARLY SALES

In January 2018, a few months after Cacioppo and her team had started writing code for Vanta, they got accepted into Y Combinator.

“YC would be helpful for what I now know is prospecting: getting early customers and users. So while there were some trade-offs to doing the program, I knew it would be worth it for that early customer momentum.”

I had no selling experience whatsoever — the last thing I sold prior to starting Vanta was Girl Scout cookies.

Being a member of the popular accelerator opened up a network of fellow YC founders, and it was through that network that Vanta ended up securing people management platform Lattice as one of its first customers.

“YC has Bookface, sort of an internal Hacker News that has a bunch of information on prior companies. Our partners went through those company lists with me and helped me prioritize who might need a SOC 2 that I could reach out to. And what I generally found was YC founders are extraordinarily kind to one another and would take meetings with early companies, even when it wasn't totally clear they had a business interest in doing so,” says Cacioppo.

From those early sales pitches, Cacioppo learned three important lessons she imparts on other founders:

- Selling to fellow founders is a great place to start. “Early on, I learned that I very much sold like a PM, which is good and bad. I was like, ‘Let me show you what I built. And also, I will ask you a million questions.’ Because I'm curious, and I'm building a model of the user. But the sales pitch was very much an after-thought, sort of like, “Oh, by the way, would you buy this?’ Sometimes, I would do really deep discovery and then forget to send the DocuSign,” she says.“It helped to sell to other founders because they're much more tolerant of that approach. It especially helped us sell to technical founders because they're much more motivated by talking about a product than being sold on it. So that inadvertently worked in my favor.”

- Don’t do two sales calls when one will do. “My initial sales process was to do a first call of discovery where I’d ask the prospect questions, and then at the end, explain what Vanta did. Generally, the reaction I'd get was excitement for the product but disbelief that it actually worked. So then I’d say, ‘Let’s do another call, and I'll show it to you.’ On that second call, I’d show them the product, and they’d be wowed that the product did exactly what I said it would do. I thought I was all set with this genius two-call sequence,” says Cacioppo. “But after a second call with this one founder, he said, ‘That should have just been one call where you showed me the product immediately, and the deal would’ve been done in 30 minutes.’ And he was precisely correct. So that’s what I did going forward.”

- Ask for feedback from salespeople outside of your organization. “About six months in, the calls started to get boring because I'd done them so many times. It was kind of working, but I wanted to optimize. So I started going to salespeople outside of Vanta and asking them to review my process, scripts and conversion percentages. What I was doing worked some of the time, but I didn’t know how much better it could be until I asked for outside expert opinions.”

RAISING A SEED ROUND

In the spring of 2018, Vanta graduated from Y Combinator and decided to raise its Seed Round. “It was ‘easy’ in that we had the momentum of coming out of YC,” Cacioppo says. “And honestly, we had nice backgrounds — fancy undergrad degrees from Stanford, had worked at Dropbox — all those unfair advantages.”

Even so, it was no walk in the park. Vanta was a wildcard. It was creating a new category, and Cacioppo had to paint a picture for investors of her vision for SOC 2, one that not everyone believed would come to fruition.

The thing that very much threw people for a loop was our pitch: “We're gonna go SOC 2 all the startups!” And at the time, no startup got a SOC 2.

In one meeting, a partner turned to Cacioppo and said, “Sounds great, but this just doesn’t happen.” “Oh, but I promise you, it will!” was Cacioppo’s retort. Despite her unwavering enthusiasm, she still got rejected by investors who didn’t understand why Vanta was trying to help startups get SOC 2s when no startups they knew were trying to get one.

“And I think that was a very reasonable read of the situation,” says Cacioppo. “But what we had was, one, there was going to be more and more pressure on software companies to prove their security. And two, this insight of, 'Startups would get a SOC 2 if it were easier and took them less time.' So the combination of more pressure from customers and reducing the time it takes to get one of these things—that's going to make more startups get SOC 2s. That was our thesis.”

And none of the “no’s” shook Cacioppo’s belief in that thesis.

I'd spent a year validating the idea. And because I'd spent so much time validating, whenever I got a rejection from an investor, I was like, “Cool, I look forward to proving you wrong.”

By April 2018, Vanta had closed on its Seed Round, but it would be a full three years before it raised a Series A, amassing $10 million in ARR before doing so.

GAINING TRACTION

The first big milestone for Vanta was when it started steadily acquiring one new customer per week. Within the first six months, it ramped up to roughly two new customers per week. “It was so exciting just seeing that velocity there and being able to look back and be like, ‘Oh, remember when it was one a week and it seemed like such a big deal, and now, it’s three a week?’”

Vanta was gaining word-of-mouth traction as a product that got startups a SOC 2. Naturally, then, people were asking, “Well, how many SOC 2s have you gotten for your customers?” “The initial answer was zero,” says Cacioppo, “which didn’t feel great.”

Around 20 startups were already paying Vanta to streamline the process of SOC 2 preparation—but Vanta had yet to help any of those customers actually go through the required audit. It was time to get the ball rolling. For their very first audit, Cacioppo flew to Colorado, sat in that auditor’s WeWork and pulled information from the database to ensure they had everything they needed to complete the process.

“That was a combination of product development and research, of figuring out what auditors need to grant a SOC 2 and also figuring out what an audit actually looks like,” she says. “On top of that, we felt this immense pressure to deliver because we'd already told this customer it was going to work. We needed it to work.”

It worked. “And then afterward, we told that customer they were the first one,” Cacioppo says with a laugh. At this point, Vanta still didn’t have a real website or a marketing team and still hadn’t raised a Series A. What gives?

“In retrospect, we were probably a little too clever for our own good,” she admits, “but at the time, the thinking was one, we wanted to make sure we could actually do this thing. Going into your first audit with 20 customers is frightening enough. Did we really want that number to be 100?”

And she wanted to preserve Vanta’s first-mover advantage for as long as possible.

Once it started working, we realized this was actually quite a deep and ripe area, but everyone else still thought SOC 2 was this tiny, niche thing that only big companies got. We wanted to stay under the radar so we could get ahead because we didn't want a bunch of copycats.

By early 2019, the Vanta team had confidence that they had found product-market fit because they no longer had to go out and find customers—the customers were finding them, even though they’d made it exceedingly difficult to do so. At this time, if you went to vanta.com, all you’d see was a barebones homepage with a company email address. Even so, the team was starting to get two or three emails a week, all through word of mouth.

At this point, the team consisted of engineers and Cacioppo, but now that they had this internal confidence that they’d found product-market fit, they hired a support team, then customer success and lastly, sales.

RAISING A SERIES A (FINALLY!)

In the startup world, it’s a commonly held belief that a SaaS company should raise a Series A as soon as it hits $1 million in ARR. So why did Cacioppo wait to fundraise until Vanta had 10 times that amount?

- Money wasn’t blocking the company’s growth. “We were basically operating at cash flow breakeven. The things blocking our growth were things like not being very good at hiring or setting up the great people we did hire to do their job well. We definitely had our issues, but they didn't feel like issues that money was going to solve.”

- Selling to customers was the priority, not selling to investors. “I realized I could spend time selling customers on Vanta and getting more revenue, or I could spend time selling investors. And selling customers and getting more ARR was actually working quite well.”

- As ARR grew, so too did the likelihood of success when fundraising later. “The more ARR we had, the easier the investor conversations.”

I figured if investors like Series A's that had a million dollars of revenue, they probably really like Series A’s with $2 million of revenue and even more.

What caused her to finally raise a Series A?

- Vanta needed to sprint ahead of the competitors that were cropping up. “The secret got out that SOC 2 for startups was, in fact, a very good business. I wanted to accelerate growth before the competition caught up.”

- Not raising money was negatively impacting Vanta’s reputation. “Folks thought we were much smaller than we were, which didn't feel like a great position in the market. Plus, when we were pitching candidates, they'd be like, ‘Oh, I'm not sure I want to join a seed-stage startup.’ And we'd be like, ‘No, no, we're actually more like a Series B startup!’ It was very confusing and annoying for everyone.”

- As the employee count grew, she didn’t want to take unnecessary risks. “You can operate at cash flow breakeven, but as you're growing your team (and our team was about 50 people at this point), you have to think about how many months of payroll you have in the bank. If we were to miss sales targets for two months and went out of business, I'd feel really dumb. We did not need to fly that close to the sun.”

In May 2021, Vanta raised a $50 million Series A led by Sequoia Capital. With that funding, the team accelerated hiring, invested in marketing and, yes—finally put up a proper website. They also announced support for two highly-requested certifications, ISO 27001 and HIPAA, which paved the way for Vanta’s expansion into new customer segments.

LOOKING FORWARD

Since 2018, Vanta has grown from manually assisting that first SOC 2 submission in Colorado to automating compliance for many more frameworks, including GDPR, HIPAA and USDP, for customers around the world. It now has offices in the U.S., Australia and Ireland. And while the company got its start going where no company had gone before (getting SOC 2s for startups), it has broadened its ambitions by creating another new category: trust management.

“I'm re-centering on a lot of the founding pieces of Vanta,” says Cacioppo. “We're known for SOC 2, but SOC 2 is just one tool to demonstrate the security you have and build your business. We built the initial product around it because it seemed like the closest thing to an industry standard, but it's not special otherwise.”

“Now that we feel very confident in our ability to get SOC 2s (we've gone from that first one to literally 1000s), it's really about finding other ways for companies to uplevel their security and demonstrate that to grow their business. So we’re building things around trust reports and security status pages. That alignment of business growth and securing your company is really at the core of Vanta.”

That renewed focus on trust is reflected in Vanta’s first acquisition. Trustpage is a security startup that enables businesses to publish a hub where customers can see compliance certifications and real-time security updates, granting them confidence and peace of mind.

With its first acquisition, $203 million in total funding and more than 5,000 customers—including Quora, Gusto and Autodesk—Vanta is continuing its move upmarket. For acquiring enterprise customers, here’s what’s worked for Cacioppo:

- Partnerships. “When breaking into enterprise, it’s about finding the ways in. For us, we've started building out a partner program and equipping virtual CISOs and consultants with Vanta to go serve customers that we probably would not acquire or touch on our own for a couple of years. Those tend to be brick-and-mortar businesses. That's starting to work now. When we started, we never would’ve thought we’d have a law firm as a customer, so that’s exciting.”

- Acquisitions: “Acquisitions have been big. A Vanta customer gets acquired into a bigger company, and that ends up being a great way to show what Vanta can do and why it's important. It gives us all these internal sales champions, and we can use that to break into much larger companies than we would be able to by trying to go in through the front door.

Every founder hopes to make their mark, and while announcing you’re going to “SOC 2 all the startups” may not sound like the most exciting way to go about doing that, for Cacioppo, her quest to secure the internet holds a deeper meaning.

“The story of the internet continues to be the story of our time,” she wrote in a 2013 blog post explaining why she quit her job to build software. “If you truly want to follow — or, better still, bend — that story's arc, you should know how to write code.”

A decade later, Cacioppo is truly bending that story’s arc as Vanta furthers its mission: restoring trust in the internet.