This article is by Joanna Wiebe. The original conversion copywriter, she is the founder of Copyhackers and co-founder of Authority Figures. Follow her on X and LinkedIn, and subscribe to her newsletter on Substack to track work toward her upcoming book, Money Words.

You’ve been in boardrooms and on Zoom calls where your whole team pores over new homepage copy or onboarding email copy line by line, word by word. You rewrite it until it sounds just right. But what if just right is actually wrong? What if the words you use (accidentally) stir the wrong reactions in your users and prospects?

For an example far flung from the world of tech, consider the wording used on the ballot for the 2016 Brexit referendum:

- Remain a member of the European Union

- Leave the European Union

Now consider a concept covered back in elementary school: antonyms, or opposite words. When you were learning about antonyms as a child, you may have found yourself facing a series of flashcards that went like this:

Right. Wrong.

Left. Right.

Black. White.

In. Out.

Up. Down.

Those are complementary antonyms, and our brain likes them. What is the complementary antonym for the word “leave”? Is it “remain”? Or is it “stay”? I’ve presented this question to people in the UK, Australia, Canada and the US, and the room always answers the same: the opposite of leave is stay. In their 2018 analysis of the Brexit ballot wording, Farrow et al identified that, because remain/leave are not complementary antonyms, remain required more cognitive effort for voters to process than leave required, and so “this may have biased the election results towards ‘Leave.’”

Given that the British economy was on the line and that 57% of people from Great Britain would come to believe it was wrong to leave the EU, what if the higher-ups had worded the Brexit ballot differently?

For another example, consider also the multi-billion-dollar IVF, or in-vitro fertilization, industry in the US. The average cost for one cycle of IVF is more than $12,000 USD, and more than 50% of patients require eight cycles. Wouldn’t it be nice for folks if insurance covered some or all of those IVF costs?

In a 2021 study, people were asked which of the following they would support insurance coverage for:

- Fertility disease

- Fertility condition

- Fertility disability

The study revealed that “fertility disease” got 4.6x the support that “fertility condition” got. And “fertility disability” got 1.7x the support “fertility condition” got.

But we don’t call it “fertility disease” or “fertility disability.” In fact, perhaps the most referenced American healthcare resource online, MayoClinic.org categorizes infertility under “Diseases & Conditions” but never once refers to infertility as a disease in its copy. For the average American with a fertility disease, “disease” is a money word they would be wise to start normalizing.

The words we use — or don’t use — impact decisions and, in turn, money. Money words are the execution arm of persuasion.

By strategically choosing your words, you can:

- Drive team action. Two groups of participants in a 2018 study were tasked with playing the same game. One group was told their game was called “Wall Street Game” and the other group was told their game was called “Community Game.” Participants who thought they were playing “Community Game” cooperated 70% of the time, while those who played “Wall Street Game” cooperated 33% of the time.

- Make people like you more. In two 2009 studies out of New York, participants responded more favorably to those with cancer when they were called “cancer survivors” than when they were called “cancer patients.” (Wild but sadly true.)

- Motivate your team to make good decisions. When asked to wear a Fitbit at work, participants in this study (2021) were less likely to wear the Fitbit if it was messaged as something that would be good for organizational efficiency and more likely to wear it if it would be good for individual health.

- Sound more confident. When presented with a self-assessment, women in a 2010 study who completed phrases that began with “I think” — such as “I think I’m a good person” — were more likely to show signs of high self esteem than women who completed phrases that began “I feel.”

- Make more money when your business goes public. This study found that the easier a stock name is to pronounce, the better it performs in the short term.

If we can agree that the words we choose are persuasive levers — and our job is to pull those levers intentionally and strategically — then allow me to share with you two money words and one lose-money word. They are the low-hanging fruit that will help you sharpen your copy and speak better to prospects.

Your team should test these words in your website, ad and email copy. Of course, there's a tad more to it than just a simple swapping of words, so I share tons of examples to guide you and outline conditions you need to make sure you meet before plugging these powerful phrases into your copy.

MONEY WORD #1: YOU

Which of these two Google ads got a 47% higher click-thru rate?

- Ad A: [Brand name] succeeds for 87% of clients

- Ad B: 87% of clients succeed with [Brand name]

If you answered Ad B, you’re right. Now for the next question: Why?

This 2021 study explains. And the gist of it is a description of a trick copywriters have been practicing for ages: in order to positively impact persuasion, you should make the consumer the grammatical subject of a sentence.

Study after study proves it. When you lead with the brand name — rather than the user — you get poor results. Consider the following two messages about the rewards of a membership program, which were tested against each other. I’ve underlined the subject of each sentence to make it clear:

- Message A - User is subject: According to this program, consumers who accumulate $1,500 of purchases receive a $150 cash bonus.

- Message B - Program is subject: This program requires you to accumulate $1,500 of purchases to receive a $150 cash bonus.

Even with slightly longer copy, Message A, where the user is the subject, increased the likelihood of prospects converting. If you think that’s interesting, you’ll love this: Message A also increased perception among prospects that they were a good fit for the program and that the program was easy to join.

Here’s why such a small tweak can yield big results: People are filtering 5000+ messages a day, and we’re doing so by looking for signals of relevance. We’re really good at it, too. We’ve evolved to filter information. Consider how your head swivels when someone says your name in a noisy room. In marketing, studies show that when user data is used to serve more relevant ads to people, conversions increase; when user data is not used — and the ad in turn becomes less relevant — conversions decrease.

It’s likely no surprise to anyone in marketing or growth that personalization works. In a popular personalization example from 2015, DonorsChoose ran an A/B test in which, over the Valentine’s Day weekend, they sent one of two emails to 500,000 people on their list.

Email A (geo-targeted)

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

Give to a teacher,

In a school near you.

Included a classroom request in the recipient’s home state.

Email B (personalized with last name)

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

Give to a teacher,

With the same name as you.

Included a classroom request created by a teacher with the same last name as the recipient.

Email B outperformed Email A significantly. In fact, with Email B:

- Donors were nearly 3x more likely to give to a classroom project

- Donors gave more generously, nearly 3x as much as donors for Email A

- More lapsed donors (who hadn’t donated in years) reactivated

The reason DonorsChoose ran this test was because their team had learned that people donate significantly more money to hurricane relief funds that have the same initials they do. As in, your friend Kylie donates more to Hurricane Katrina.

In another personalization study, when job seekers were shown ads for job openings on LinkedIn, and the ad included the name and photo of the seeker being targeted, three things happened: intent to click increased, interest in the job increased, and the general feeling toward the ad was more positive.

A word of caution: Studies (and about a billion anecdotes) have also found that personalized ads that seem to know the person too well can negatively impact conversion. Catherine Tucker of MIT tested two ads against each other that went basically like this:

- Ad A - No Personal Info Used: “Help girls in East Africa change their lives through education”

- Ad B - Personal Info Used: “As a fan of Beyoncé, you know that strong women matter”

Initially, Ad B - Personal Info Used did not perform well. But before we get overly skeptical about the power of personalization, something unexpected happened midway into Tucker’s experiment. Facebook instituted new privacy settings that gave users more control over the use of their personal information.

After this privacy change, Ad B - Personal Info Used became nearly twice as effective as Ad A. The personalized ad went from being a dud to being a clear winner. Why? As explained on HBR: “when consumers are given greater say over what happens with the information they’ve consciously shared, transparently incorporating it can actually increase ad performance.”

So our objective is to increase the perception of relevance, without overstepping. This is in keeping with classic copywriting advice from David Ogilvy:

“Do not address your readers as though they were gathered together in a stadium. When people read your copy, they are alone. Pretend you are writing to each of them a letter on behalf of your client.”

To achieve true personalization, we’d ideally use our prospect’s name. But in the absence of having a person’s name (like on your website) or having express permission to reference it (like in an ad), we need a substitute.

Enter the word “you.”

“You” has made a powerful appearance in some of the biggest ads and best-known copy of all time. Consider what some argue is the first value proposition ever crafted (by Rosser Reeves for M&Ms): Melts in your mouth, not in your hands. A quarter of its words are referencing me! Other examples:

- You’re not you when you’re hungry. (Snickers)

- You’re in good hands. (All State)

- You’re worth it. (L’Oreal)

A money word that is almost without compare, “you” tells the prospect that the copy they’re reading is about them, without actually using their name.

This is known as self-referencing, which basically means a person can see themselves in what they’re looking at. Self-referencing increases memory of a message and has been effective in advertising since the first dairy farmer hung a shingle that went, “Your wife called. You need milk.”

Apple.com is great at using and leading with the word “you” throughout its copy. On its MacBook Pro page (in Canada), the words “you” and “your” are used 23 times; compare that to 19 uses of “MacBook Pro” on the same page.

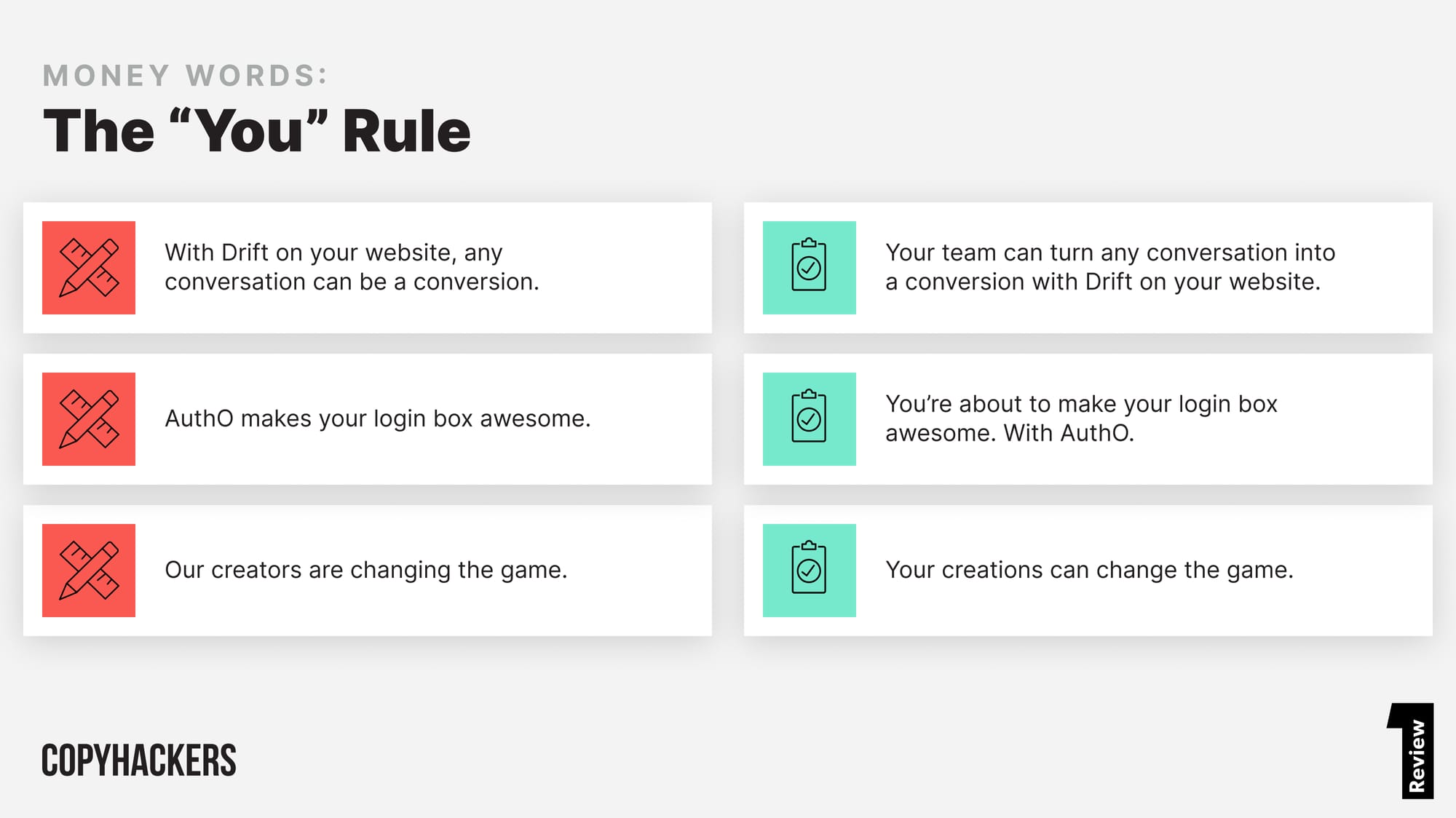

You’re likely already using the word “you” in your copy. Now here’s how you turn it into a money word: You rewrite every sentence on your website to begin with you or a variation of it, such as your. So you turn this:

- MacBook Pro lets creativity shine.

Into this:

- Your creativity shines with MacBook Pro.

Importantly, you’re expressing the same message — what you’re trying to communicate doesn’t change. You’re just rewriting the copy so that the word “you” or “your” becomes the subject of the sentence. The what is the same; the how is optimized.

Consider the following before and after sentences. Which one makes you feel like the solution is more likely to be a good fit for you? Which feels more relevant to you?

You may wish to know that, in copywriting, this is called The You Rule. You can and should use it everywhere, repeatedly, even as you get sick of it. You’d be surprised how few people notice that you’re repeating the word “you” at the start of every sentence. In fact, you may not have noticed that the last half dozen sentences you read make “you” the subject. You don’t notice the repetition because you feel like you’re reading about yourself — which is the most interesting subject for every person on the planet.

(And to be fair, if you did notice, well, I’m laying it on a little thick.)

Conditions for this money word to work:

To get the most out of making “you” the first word in a sentence, at least the following must be true:

- The offer needs to be relevant to the reader. If I’m not in the market for a new MacBook Pro, no amount of you-ing is going to convert me.

- The message itself should be positive. So avoid, “You need to stop sweating so much.” Instead try, “You deserve to live sweat-free.”

MONEY WORD #2: GET

“Pain before gain” is a mantra in copywriting. You want to lead with a prospect’s pain before you mention what they’ll gain from using your solution.

An entire series of money words exists for pains, problems and loss aversion. But because SaaS, app and tech website copy is largely gain-oriented, let’s focus on gain messaging, where benefits are on the page and the money word of note is get.

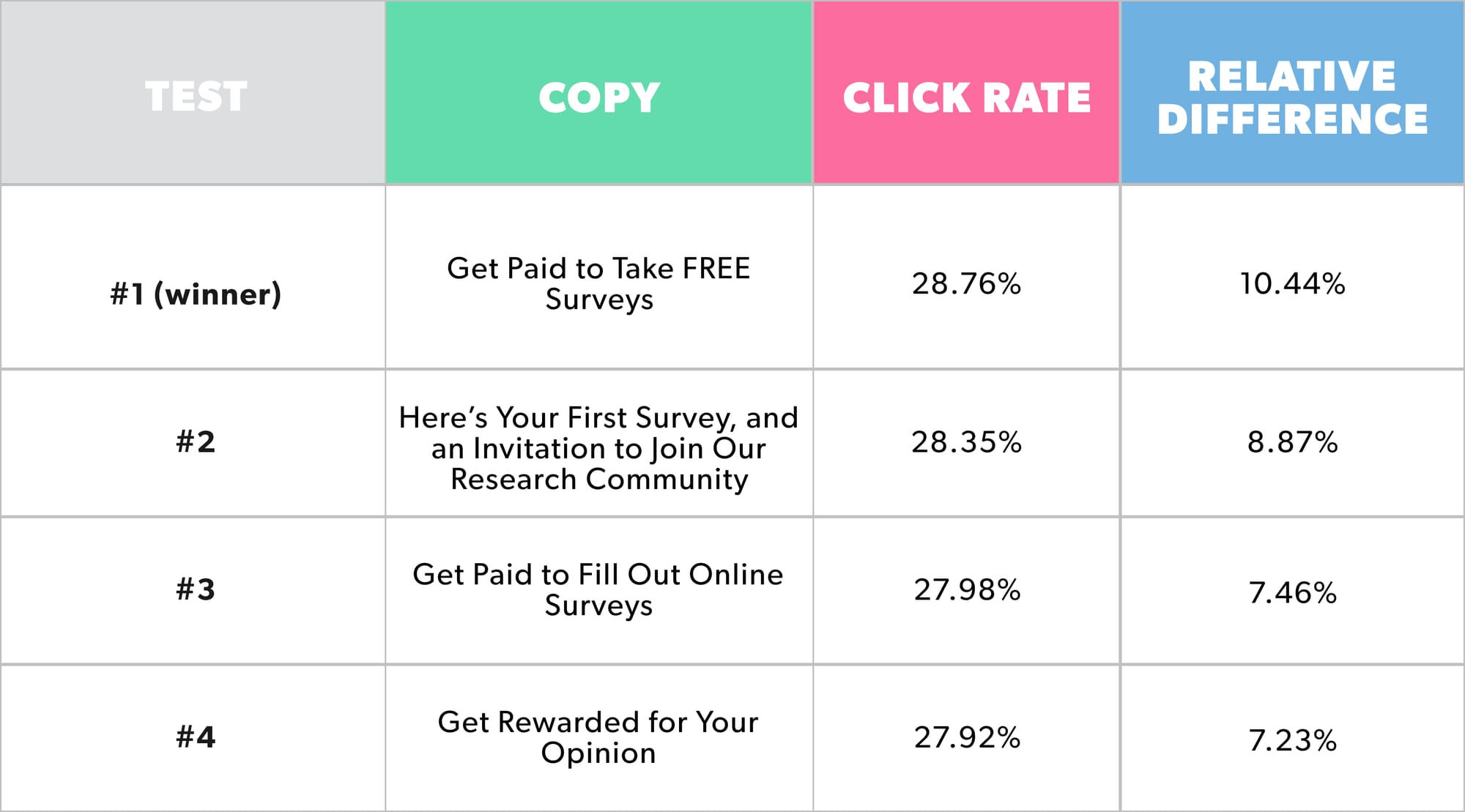

In a 10-way headline split-test, three of the four top-performing headlines began with the word “get”:

None of the six low performers began with, or even included, the word “get.” And get-focused headlines outperformed such seemingly strong contenders as “Set Up Your FREE Account Today and Start Earning Money!” (CR = 27.35%, RD = 5.03%).

“Get” is great in headlines. Uber uses it twice in their homepage headline (Aug 2023 Canada):

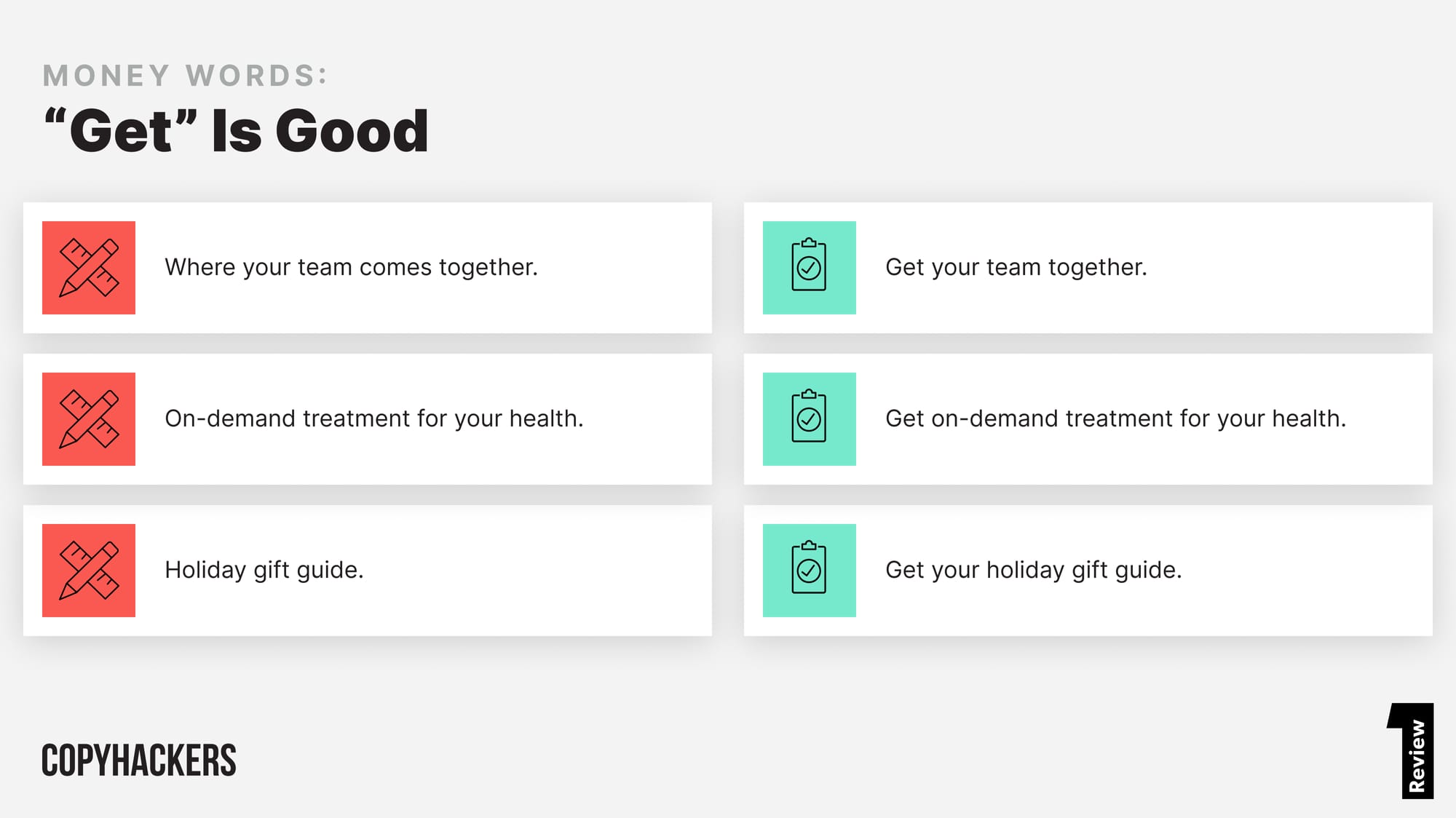

And the reality is that using this money word is as simple as rewriting almost any benefit- or outcome-oriented headline to begin with “get.” So you go from this:

To this:

Or you can rewrite a friction-filled call to action. In a two-way split test of the button copy on a SaaS pricing page, my team saw a 39% increase in clicks on Variation B (“Get started”) versus Variation A (“Sign Up!”).

Let’s take a look at some before-and-after headlines. Note that these changes will seem very minor, and that’s part of the power — like design, good copy goes unnoticed, allowing the reader to focus on what they want.

Get is good, almost without exception. However, if you’ve found that your prospects perceive your solution to be higher risk – for example, if you’ve created a new category or if there are high switching costs – then you may need to first decrease any sense of uncertainty before applying get-focused messaging.

In this foundational study, people preferred a certain outcome over an uncertain outcome without fail. When asked, “Which of the following would you prefer?” 80% of participants chose the risk-free Option B:

- Option A: 80% chance to win $4,000.

- Option B: 100% chance to win $3,000.

So if your solution seems risky to try or buy, then before you plaster the word “get” all over your landing page, first increase the perception that it’s low-risk. You can do this by:

- Adding social proof, like powerful testimonials,

- Adding case studies or quotes from influential brands,

- Adding video demos of your product,

- Including an incentive and/or

- Showcasing trials and guarantees.

For most SaaS brands, using the word “get” can tap into your prospects’ desire to improve their lives by the acquisition of desirable outcomes. And — from a copywriting / user perspective — the word “get” is extraordinarily low friction:

- It’s short, which makes it easy to read,

- It’s easy to comprehend,

- It’s fast to comprehend,

- It takes up very little real estate (*great* in an email subject line) and

- It suggests life is going to get better (depending, of course, on the word that follows it).

And finally, consider this:

make up

Conditions for this money word to work.

To get the most out of using the word “get” in your copy, at least the following must be true:

- Your offer, statement or claim should be lower risk

- There should be a sense of certainty in your prospect that they will get the outcome they seek

You should also consider the emotional state your prospect is in when they read your copy. This 2020 study found that people experiencing rainy weather responded better to “Get $X off” messages than to “Save $X” copy.

[LOSE] MONEY WORD #3: AND

Let’s finish with a different kind of money word. What I haven’t mentioned is that, although some words can help you make money, others can actually cost you money. For now, I’m calling those “lose-money words.”

For example, which of these is more likely to get the conversion?

- Option A: Pay $15 a month for your all-access membership.

- Option B: Get your all-access membership for $15 a month.

Option B is the better bet. Not only because it leads with two known money words. But also because it does not include the word “pay,” which is an example of a lose-money word. That is, when the word “pay” appears on the screen, it introduces anxiety that my asset pool is about to be depleted.

A lose-money word gets in the way of the conversion because it introduces or amplifies:

- Friction in the conversion experience,

- Confusion in message processing (“cognitive fluency”) and/or

- Anxiety in your prospect (or their team / decision makers).

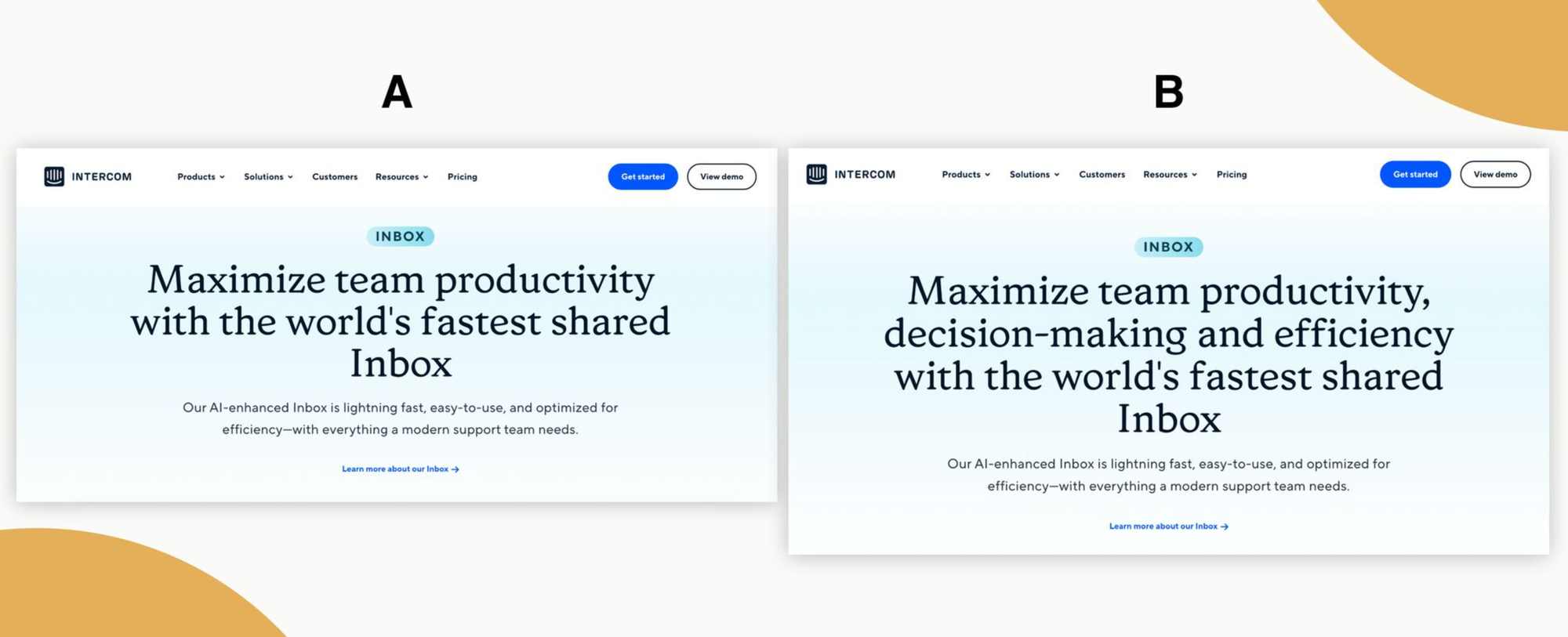

The word “and” is an insidious lose-money word. It shows up everywhere. It’s small and functional, so it seems to be friendly. But here’s the thing: “and” only appears in a sentence to join more than one thought together. As you’re about to see, our brains don’t enjoy trying to suspend a bunch of thoughts in the air as we seek meaning or try to decide. Read these two headlines:

Now close your eyes and count to ten. Now try to remember the key points covered in headline B. Kinda tough, no? Now repeat that exercise with headline A. The first headline, which is the one that Intercom has live on their site (as of July 2023), is the easier one to remember. That’s because it’s only asking you to remember one thing about the feature (shared inbox) in question: Maximize team productivity. The word “and” does not appear in it.

My general rule, which I believe I picked up in an episode of Mad Men (that series is an education in persuasion, btw), is this:

Every time you use the word “and,” you lose a conversion.

If you insist on using “and,” then you need to be cool with losing leads. Your boardroom needs to be cool with it. Every person who asks to shove another benefit into a headline needs to be cool with it. (Side note: you should not be cool with it.)

But why is “and” so problematic? Our working memory is not evolved to remember a long string of information. That’s why phone numbers are seven numbers. And that’s why you need to see an ad / message seven times before it starts to stick. The cognitive load of compound sentences, or those that include conjunctions like “and,” is too great. Even compound words are harder to understand!

But the bigger problem is a concept called interference. Interference defines our inability to recall information when we’re exposed to more than one message at a time or otherwise distracted.

- X does Y = no interference

- X does Y and Z = interference

In a perfect world, your message wouldn’t have to compete with anyone or anything for share of attention. There’d be no interference. Studies support that ideal state:

- When people are exposed to two similar ads from two brands, they struggle to remember the brands, whether they are familiar with those brands or not.

- People either remember wrong or fail to remember competing ads, whether from the same brand or competing brands.

- Even eating while being exposed to an ad creates enough interference that it can neutralize all advertising effects (such that you don’t remember the brands you saw or their messages).

Interference has been a known challenge for-ev-er, but we don’t talk about it much because, outside of being annoyed by competitor ads interfering with ours, the concept of interference is terribly inconvenient to most marketers. (Said with love by a fellow marketer.) The truth is that marketers love “and.”

We don’t like to admit that we’re creating our own interference. But, in my 20 years as a copywriter, I’ve seen that well-intentioned marketers love to squeeze another message into a headline, sentence or bullet point.

They also love “but” and “or” and commas. All of which do the same thing “and” does. And all of which are problematic for the same reasons, in your copy.

Here’s an example:

- Smart and Simple Online Safety. Powered by AI.

That’s the headline on the homepage of a terrific app. The category (“online safety”) is wrapped in a bunch of adjectives. If we cut the word “and” and one of the adjectives it’s tied to, we get:

- Smart Online Safety. Powered by AI.

Now I can focus on what it is instead of trying to wade through the weeds. And that’s not all. So many of the extra words we shove into our copy are doubling down on interference. Consider the adjectives in that headline. Think about how many times you’ve seen these words on a homepage in the last month alone.

Using the same words others use is, itself, interference. This study found that exposure to ads with similar elements reduced recall of the elements and the brand name. So the more you see the word “smart” or “simple” or “powered by AI” across a variety of messages, the less those words stick. Making them basically pointless on the page.

If we’re going to add words to the page — and risk losing a conversion each time — we’d better use words that are not going to double-down on interference. Any word on the page needs to earn its place.

So an adjective should speak to something significant for prospects, like differentiated value. Measurable outcomes. Specific pains. Specific dreamstates. Real things that help people advance. But even still! Even if you manage to rewrite your headline so it is about, say, a specific dreamstate, it should still not include the word “and.”

A rule in writing is “Skip the part the reader skips.” What if, in the example headline above, you edited out the white-noise words, which the reader skips? You might get:

- AI-Powered Online Safety.

That might not look like a sexy headline. But frankly neither did the one with all the adjectives stacked out front. And now I know what the solution is: AI-Powered Online Safety. Now I have a clear starting point. Not confusion.

The job of the headline is to move the reader to the next line.

So you shouldn’t cram a bunch of messages into your headline. Or into any of your copy. Because the job of each line is to move the reader to the next line. Knowing that, you can still include all the messages your marketing team wants on a page. You just do it in individual sentences that spend more time bringing a message to life (instead of just dropping it in a list of benefits and wondering why people don’t know what you do or how you do it).

Conditions for this money word to work:

There are times when the word “and” (or other conjunctions and punctuation marks that double as conjunctions) need to be in a sentence:

- If you’re explaining how to do something, with steps.

- Using “and” at the start of a sentence, where it improves flow between sentences.

- Anytime it improves clarity without negatively impacting memory / recall.

It’s also worth noting that “copy” and “content,” like this article, are two different things. Money words are tested in copy, not content.

WHY MONEY WORDS MATTER NOW:

If AI is your copywriting copilot, you should look for opportunities to edit money words into your AI-powered copy and remove lose-money words from it. God bless AI, but it has yet to synthesize seventy years of studies in linguistics and psychology to help us write convincing copy.

Until it does, write these 3 money words on a Post-It note on your monitor. And be sure to subscribe to my newsletter to add more insights into word choice to your dictionary.