Othman Laraki and Elad Gil got the idea for Color — a virtual clinic that supports people at every step of their cancer journey — based on a single technical insight.

Both former Google product managers, they’d started a company called Mixer Labs together. After getting acquired by Twitter, Laraki and Gil took on VP roles in product and strategy, respectively. The two were hanging out on Twitter’s rooftop when Gil pulled out a hard drive of his fully-sequenced genome. That sparked a discussion about an image circulating online at the time, showing that the cost of genetic testing was sinking faster than Moore’s Law. Laraki and Gil figured they must be able to engineer a genetic test far cheaper than the $4,000 Gil had just paid.

The idea hit close to home for Laraki. His grandmother had died from breast cancer. His mother is a two-time breast cancer survivor. And he’d done some genetic testing himself — learning he carried the same BRCA2 gene mutation that put his mother at risk.

“Using genetic data to generate insights is a very software-driven process. That resonated with me as a software engineer,” says Laraki. With that insight, he and Gil left Twitter to start building a solution to make cancer screening more affordable and accessible.

But they didn’t know a thing about the market. So Laraki grounded this learning process in something he did know — building a product.

This kicked off a years-long, iterative process of constantly revisiting his assumptions. Eventually, he realized a direct-to-consumer testing service wouldn’t work, and Color expanded into a virtual cancer clinic, selling instead to employers and health plans. Color has since landed partnerships with healthcare brands like the National Institutes of Health and the American Cancer Society — and earned a billion-dollar valuation along the way.

We’re moving past the market identification and validation phases, past the Statista research and TAM data to talk about what it actually means to build a product in a market you’re unfamiliar with — which, maybe counterintuitively, is how Laraki learned the healthcare industry.

Here’s his advice for founders who are early in their journey.

Watch for these failure modes of building as an outsider

Building in a new industry demands balancing both first principles thinking and acknowledgment that you’re probably not the first person to tackle this problem. “When you enter a new space, it's important to be willing to question the status quo, but also have a lot of humility,” says Laraki.

He wishes he took his own advice back at the start of his journey, when he was a software entrepreneur wading into the foreign waters of insurance giants and research labs. Beware these failure modes so you can prime your mindset for the learning ahead:

Clinging to initial assumptions. Don’t let your early wins — like fundraising or recruiting a stellar early hire — give you false confidence about your assumptions in this new industry. Hold them loosely as you learn the nuances of how this space operates. “If you’re able to raise funding and hire an early team, that means you’re somewhat convincing,” says Laraki. “Your team and investors will demand a plausible plan for how you’re going to pull off something great.”

Many "good" plans fail. You need to be willing and able to assess and adjust.

Color went through a number of these adjustments, which was only possible because Laraki didn’t whiteknuckle what he believed to be correct. “It took many years and pivots to hone in on what worked. At every step, some people might feel that change is a failure, but in my experience, that’s often the wrong reflex,” he says.

The company’s first product was an affordable, direct-to-consumer genetic test. But growth was inhibited by several factors: CAC was too high, LTV was too low and the incentive structure was fractured. Customers wanted the best testing option, but it wasn’t integrated into clinical workflows or reimbursed by insurance.

The team pivoted to selling medical-grade tests to physicians. Doctors loved the product, but billing through insurance introduced a new kind of friction. “Even though we were cheaper, we were still spending hundreds of dollars just to collect,” says Laraki. “It cost us more than any margin we could make, so we needed to figure out a more efficient way to be able to access users and customers.”

That prompted another shift to offering the tests as a benefit through employer health plans — an idea Laraki had when a Stripe founder used the test and asked to roll it out to his employees. While the enterprise business model was effective, it was still too narrow. “Big companies don’t want to be in the business of buying individual tests. At that level, if you’re someone managing a population, you’re thinking more holistically,” he says. “You’re considering cancer and behavioral health and women’s health. We were plateauing early.”

Thinking you’re the smartest person in the room. “Oftentimes, myself included, people assume the reason something hasn't been solved is that everyone before them has been stupid, and they’re the first smart person to show up,” says Laraki.

So be humble throughout this process. You should assume that the field you’re entering is filled with incredibly smart, diligent people. “You're going to be naive at the beginning, and that naivete is excused if you show up with humility. It's very heavily punished if you show up with arrogance,” says Laraki. “I realized over time that when I saw people behaving in ways that I thought made no sense, it was actually because I just didn’t understand their incentive structure.”

Falling for false positives. With the early ammunition of fundraising, it’s easy to lean on a warm network for product leads. But Laraki says to be careful not to mistake influence for traction. Startups can score customers this way without doing the legwork of cracking the go-to-market code in their industry.

“Are people really buying the product because it wins on the incentive side, or did you win out of influence?” says Laraki. “I see a lot of companies get a few early wins that came from either luck of influence and assume they have product-market fit. That happened to us, too. We got some early wins because of influence and realized it wouldn’t generalize or scale up.”

Don’t mistake false positives for product-market fit.

Laraki has seen this happen when a startup gets a great name VC or some other bonafide — like having the ex-FDA Commissioner on your board — and influences some early wins. “That can cloud whether you really have product-market fit,” he says.

Start by untangling the flow of money and decision-making

Charlie Munger famously said, “Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome.” Most technical folks underestimate the “why” behind the status quo, assuming incompetence is at play — and not deeply rational decisions made under constraints.

Laraki thought more like an anthropologist than a technologist by learning the decisions and sequence to complete a transaction in the healthcare industry. He says the best way to do this is by setting up exploratory conversations with industry leaders you might sell to, like a claims adjuster in insurance or a procurement manager in construction, for example.

“One of the mistakes I see founders make is not talking to people enough,” says Laraki. “I meet a lot of healthcare companies where you can tell, even though they’ve been in the industry for a while, they’re still naive about the marketplace. They don’t understand their buyers in a deep way.”

Finding these people is a numbers game. On a daily basis, Laraki recommends poring over news stories, LinkedIn posts, research papers — any industry chatter you can find. And when you notice people doing interesting work that’s relevant to your problem, reach out to them thoughtfully and try to have a conversation.

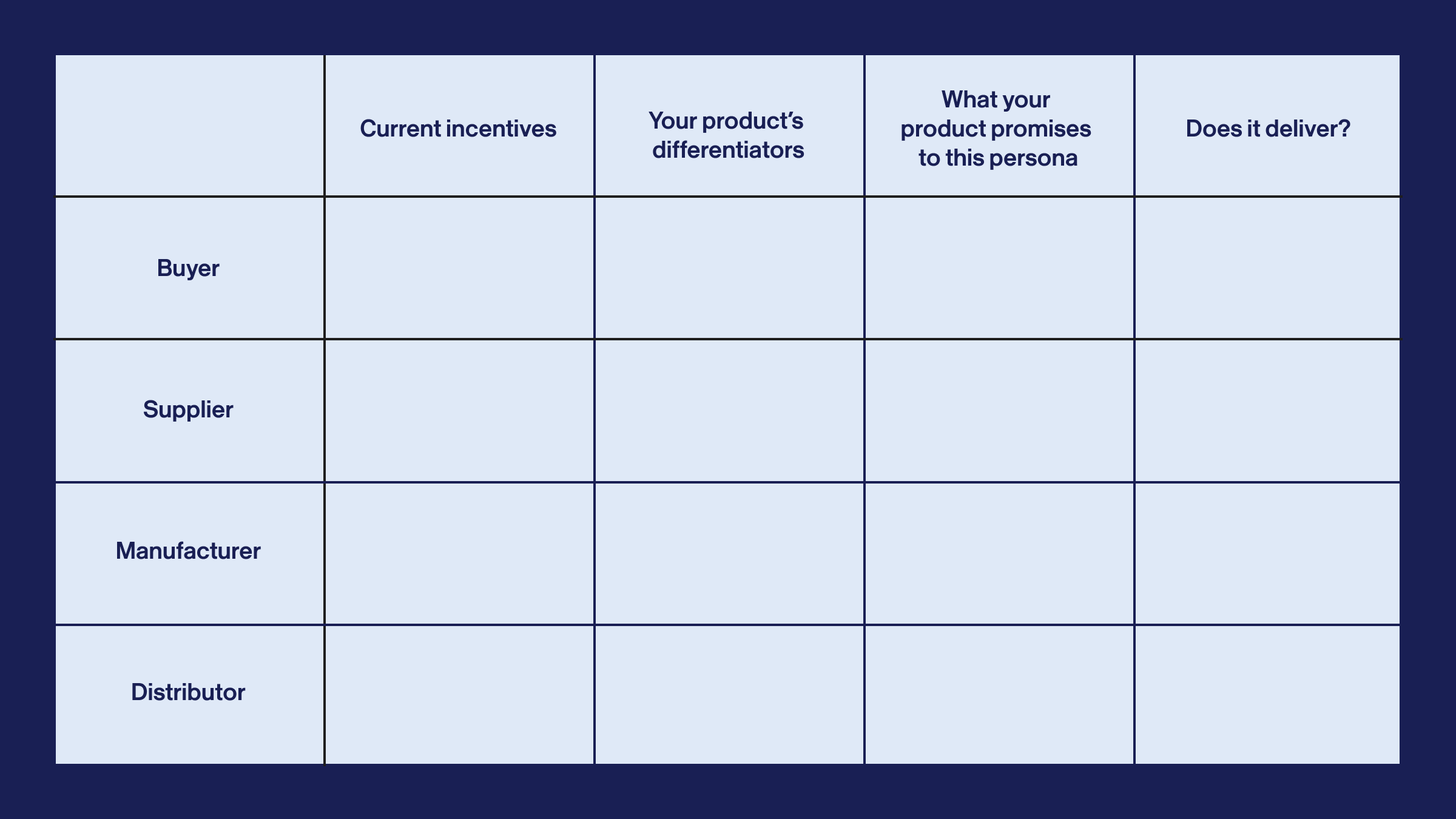

One of your main goals in these conversations is to map out how a transaction would move through all the “pots of money and incentives,” as Laraki puts it. For example, he looked at:

- Suppliers

- Manufacturers

- Distributors

- Buyers

An enterprise market is like a mosaic — from afar it looks like one cohesive image, but step closer, and you’ll see a constellation of smaller pictures. Laraki says that most founders get caught up on the buyer and assume there’s just one. “As consumers, we think about one buyer and one seller,” he says. “But in many industries, with healthcare being an extra-complicated version, the process of making a purchasing decision and acting on it can be more complex. It’s worth being flexible about which buyer you want to sell to.”

The most impactful learning will come from going into excruciating detail of how a purchase actually happens. “Who influences, who decides, who sets the price, who sets the terms, how the transaction actually occurs and how you get paid — this is what you have to untangle,” he says.

By unpacking these factors, Laraki learned that the reality of the healthcare industry was far more complex than what most people see on the surface. “The thing that makes healthcare difficult is that the beneficiary of your services are regular consumer humans. The economic buyer is either the health plan or a self-insured plan by big employers or the government. And then there’s the clinician,” he says. “Selling into healthcare requires all those incentives to connect. Everyone likes to say incentives are aligned with patients, but the reality is that’s not the case.”

Laraki shares an example: “We were very naive about how insurance works. You and I could both have a Blue Shield card, but you could be on an individual plan and I could be on a self-insured plan with a big company. And in reality, it’s actually the big company that’s the insurer and Blue Shield is just the administrator,” he says. “That introduces a very different dynamic around what you want to pay for and what’s worthwhile.”

There’s also the added complexity of regulation in healthcare. But again, through the process of speaking with experts to learn how the market worked, he was able to unpack where the real challenges were. “Usually people attribute the challenge of healthcare to regulation. But I think that’s completely wrong. Yes, regulation adds some overhead and cost — we’ve dealt with the FDA, HIPAA, CLIA — but those are all manageable,” he says. “What makes healthcare really difficult are the two big dynamics of the splintered buyer problem and that it’s a non-liquid market.”

All of these learnings will help you map out how a purchase happens in your industry. Once you have it, figure out if incentives align with all the different players involved in that transaction flow.

“What do you offer that’s different, and how does that difference influence the incentives of all participants?” says Laraki. “If some participants are disadvantaged by your product, you should figure out what can overcome that. Is the value you offer so big that other participants will pressure the blockers?”

The last step here is thinking through how granularly your buyer interacts with the market. “Sometimes you build amazing technology, but the buyer sees it as a feature within the solutions they purchase,” says Laraki.

Make sure you’re not trying to sell a steering wheel to someone who wants to buy a car.

- How understanding buyer motivations helped shape Color’s product:

Laraki realized his core assumption around building a testing solution wouldn’t be a viable product. In healthcare, the buyer is splintered across multiple entities: consumers, insurers and health plans, employers and clinicians. “We basically tried every buyer until we found the one that worked. We thought the challenge was regulatory. But what makes healthcare hard is that the people who pay, benefit and prescribe are all different entities — and often, their incentives run counter to each other.”

This led him to pivot the product from a genetic test to a virtual cancer clinic. Cancer, he learned, was a top cost driver for key buyers. A genetic test was merely a feature. Big insurers and employers would only pay for a solution that could slash costs associated with cancer.

Assemble a roster of experts — on your advisory board and your team — to help shape your product

It’s never too early to find creative ways to recruit experts, either as advisors, partners or teammates. A quality over quantity approach led Laraki to reach out to unsexy experts. “We found that ‘celebrity’ experts weren’t the best or most missionary. The most famous people get solicited constantly, so they might have less time for you,” he says. “For us, it was people deeply committed to science who ended up being very open about moving the field forward,” he says.

Go one or two steps down the management tree to identify the people actually executing the ground-level work. Laraki says Color still does this routinely. “We have a brainstorming discussion focused on the question of, ‘Who are the top brains in the world who can help our thinking and help us make a better product?’ We make a list and start reaching out to them.”

Find advisors who are doing the work — not the ones who spend most of their time talking about it.

To increase the success rate of cold outreach, Laraki found it helpful to lean into the company’s mission and his own personal connection with the problem he was solving.

“We cold emailed Mary Claire King, who established the link between cancer and genetics. She's an incredible scientist, but she had never worked with businesses — she was almost anti-business,” he says. “We approached her by saying, ‘Hey, here’s our story. We want to challenge the model, but we won’t cut corners because we have personal connections to this work and are deeply technical and rigorous.’ And after putting us through the ringer to confirm we knew what we were talking about, she became a very close scientific collaborator.”

Of course, incentives are a necessary part of these arrangements, whether that’s cash, equity or an ongoing role. “A simple hourly rate helped keep things straightforward, especially for people outside of tech. Many don’t know how to reason about equity, so an hourly cash model is often easiest,” he says. But you can also get creative here, depending on your industry. “Many folks just wanted to help us and didn’t accept compensation. So if you’re working with scientists, another way to compensate them is to sponsor or partner on research they find valuable.”

Once you establish a working relationship, getting your product in the hands of these experts can teach you a lot about what your industry’s buyers care most about — and the product attributes that matter most to them. “The best way to draw boundaries around an MVP is with your buyers so they can provide a sense of what they would be comfortable with as a baseline. This is what we did with genetic counselors and scientific experts,” says Laraki.

- What Laraki learned by getting the product in the hands of experts:

In healthcare, a product with scientific rigor is a non-negotiable to win credibility. It took Color two years to launch. “The rigor you establish at the beginning will last for the entire life of the company, for better or worse.”

Sharing early versions of the product with experts helped validate Color was indexing on the right things. “The main validation was scientific and clinical rigor. We were hearing from practitioners that we were building a high-quality product that’s also 1/20th of the price of what everyone assumes it should cost.”

Laraki didn’t just think about assembling industry experts as advisors. He also wanted experts inside the company at the two most important sides of the product-building process: engineers and scientists. Their common denominator was that they were mission-oriented and had a get-shit-done attitude. “You’ll never have perfect information and you’ll need to adjust often, so you need people who default to action vs. paralysis in the face of uncertainty.”

Laraki recruited some of the best engineers he worked with while at Twitter and Google. The other was looking to academia for people who were deep in the science world and understood the core of what they were trying to do.

He was surprised to discover that several engineers he worked with at Google and Twitter had a passion and sometimes even an early-career background in healthcare. For some, joining Color represented the opportunity to return to their early passion armed with a strong engineering skillset. “To this day, it’s still a big differentiator for us,” he says.

But while the early team had a deep scientific bent, it lacked experience from the business side of the industry. In cases where you need to deeply iterate on the go-to-market motion, Laraki cautions against hiring “senior” people who will rigidly rely on just one playbook to win. Experience needs to be matched with openness, creativity and resilience.

Investing in experts across the board prompted another evolution of the product into a huge opportunity. At the onset of COVID, Color was a large-scale testing and vaccine distribution infrastructure for public health systems, cities and states. They had the logistics, software and lab infrastructure and could repurpose it fast.

“Everyone was ignoring the delivery part. When the rubber hits the road, vaccines or tests sitting in a warehouse don’t get deployed to large distributed populations,” Laraki says. This transformed Color into a vertically integrated healthcare company with 50-state medical licensure and operational expertise in public health delivery, shaping the product into what it is today: comprehensive virtual cancer care solution sold to large employers, unions and health plans, in partnership with the American Cancer Society.

If there are real COGS in your business, run this unit economics exercise

Laraki’s and Gil’s initial insight came from the dwindling cost of genetic testing. But it required one important step to actually see if it was a viable business — crunching the numbers in a unit economics test spreadsheet.

“We looked at the cost of building a genetic test at the beginning and unpacked it in great detail. We made a list of all of the pieces that went into the cost to do a genetic test,” he says. “The core thesis was that we could build a high-quality test and put it on the market at a consumer price point.”

Laraki says it’s critical to embrace a first principles mindset here. “Don’t put placeholders in a spreadsheet with big error bars. Go through the painstaking process of figuring out each step that’s needed to deliver your product and figure out how much it’ll cost,” he says.

Since a lower price was Color’s differentiator at first, Laraki says the goal was to charge a few hundred dollars. “This was back when the Vitamix was very popular, and they were $300. We thought, ‘We need to be cheaper than a Vitamix. So our initial price point was $250,” he says.

Starting backwards from that price point, the team looked for wiggle room in the unit economics, which helped him learn about all the components that go into the cost of a genetic test. He discovered there were a handful of items in the cost of goods sold (COGS) that dominated the cost structure. So instead of accepting the standard market price, he negotiated each component intensely.

Here’s how he found that flexibility:

- Ask for a discount. “It turns out that you can get a discount most of the time. It’s amazing how few people ever even ask,” he says.

- Bake in alternatives. The simple presence of a fallback changes the dynamics.

- Understand the seller’s incentives. For example, do they have end-of-quarter incentives? Prefer pre-payments? Or large purchase orders?

- Unbundle supply. Sometimes, supplies include a safety buffer, but that’s not always necessary. This echoes the Google DRAM story. The tail end of reliability sometimes costs more than robustly managing errors, exceptions and failures.

Newcomers often misunderstand the dynamics that drive pricing outside of the tech world, says Laraki. “Entrepreneurs think that pricing bottoms-up comes from lower costs, where their advantage is using technology to drive down the cost of services and price based on that. But in practice, pricing is more often driven by market power and incentives of middlemen who control market access and distribution.”

- The impact of Color’s pricing decision:

When Laraki ran the unit economics exercise, he learned he was able to charge $250 for the initial genetic test. But what he didn’t know was that the companies that’d been successful doing this set the price high for a reason other than COGS: “They’re like, ‘No, we’re not going to drop the price. We need to capture the margins, because market access through sales and insurance billing is what’s most expensive,’” he says. “And so if we wanted to stay a testing company, the only viable strategy would have been to sell at a high price.”

However, that initial $250 line he drew in the sand ended up setting the price in today’s market. “It all started with that choice we made and forced the market down across the board,” he says. “But for us, the real question was whether we could make it actually work.”

Study the incumbents to find your wedge (and strategy)

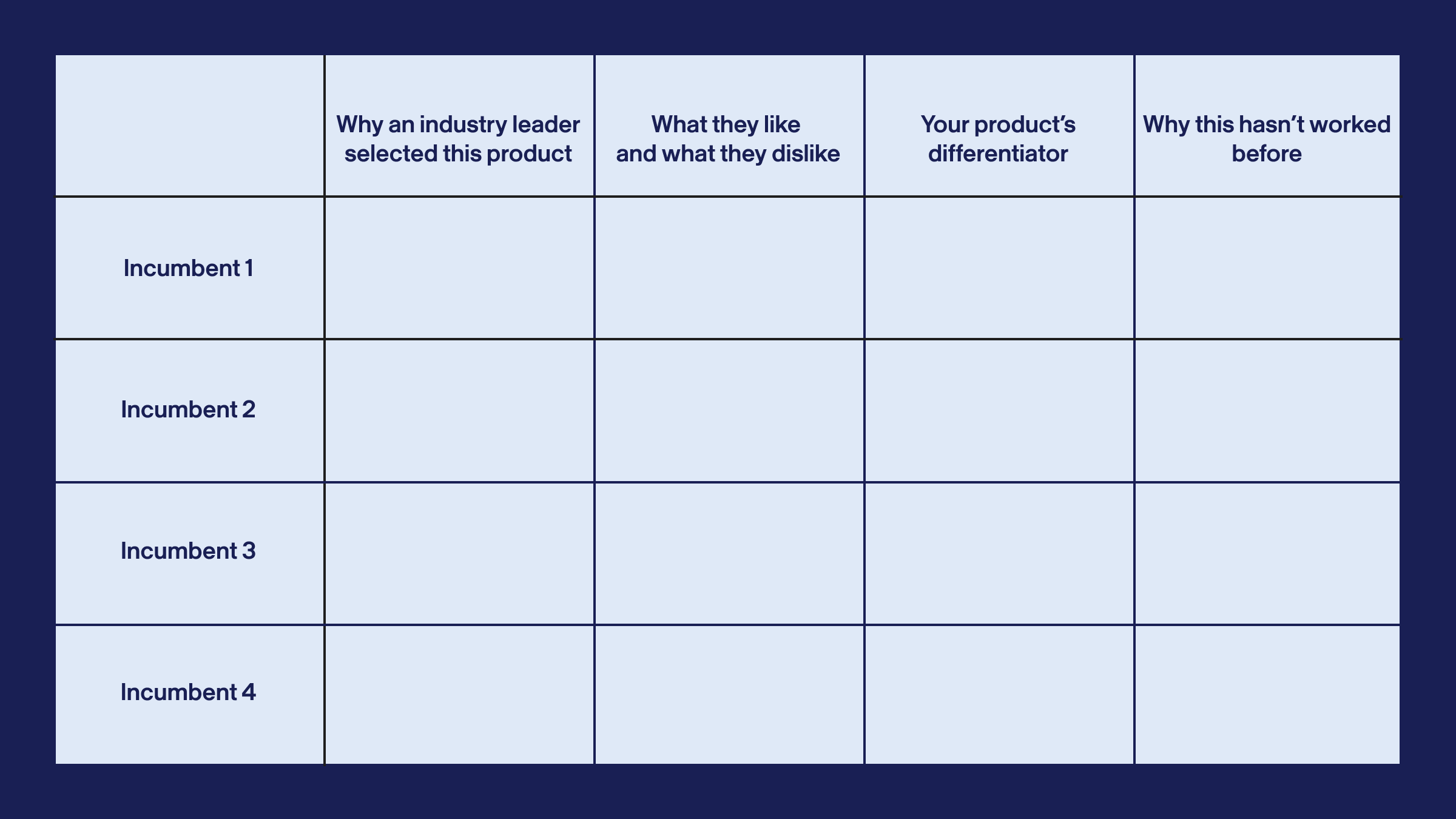

You’ve already identified your product differentiators when it comes to tracing a transaction. Now it’s time to see how those stack against existing players in the market by talking to more industry players about the products they currently use.

Color’s initial wedge was pricing. Incumbents were charging north of $4,000 for genetic testing, and Laraki’s and Gil’s original thesis was that they could unlock a bigger market by charging dramatically less.

But new technology alone isn’t a viable business model. You’ll have to unpack why your approach hasn’t worked in the past for existing incumbents. Laraki says he made the mistake of assuming standard supply-and-demand laws applied to the buyers they were originally after: insurers and doctors.

- How studying incumbents led Color to pivot the product:

There are a lot of complex dynamics in healthcare that shaped how Color would go to market. “We initially made the mistake that buyers — doctors and insurers — were on a simple supply and demand curve. If you reduce the cost of X by 90%, they would buy a lot more, or at a minimum avoid higher-priced options. But it turned out that insurers couldn’t single-source from one company. They could increase purchasing by relaxing criteria, like what you need to qualify for a genetic test. But if they did that for us, they’d have to do it for everyone else too, because individual doctors might want tests from specific labs,” he says. “Access restrictions are determined by the median or high price of a service, so being a low-cost leader doesn’t make your product easier to buy. It just gives you less margin to put to work to access the market. Access only improves if everyone drops their prices and insurers can then assume a lower cost for a given service."

This meant that even if Color offered a low price, insurers still wanted to keep restrictions on whole categories to contain costs. “We realized we were in a catch-22, where insurers introduced tons of friction to stop expensive tests from being used too frequently. Because of that expectation and friction, test vendors needed to spend a lot of money just to get paid. That, in turn, caused the cost of sales and collections to be a far bigger driver of high prices than the underlying cost of testing,” he says.

The Color team soon realized their foundational assumption was wrong, which was that if testing increased by >10x in volume, cost would be reduced by 90%. “Once we knew that was the case, we made a pretty fundamental decision. Rather than stay in the testing business, we wanted to be in the solutions business. This led us to explore the buyers who are the real purchasers of solutions, which turned out to be major employers and unions. We wanted to sell holistic services, so we set out to find out who bought those.”

You’ll also need to unpack how incumbents control stakes in the market. Healthcare, for example, is a non-liquid market. “With consumer products, if a more competitive product shows up, that product can win in the market and gain traction. But in a market like healthcare, it’s the polar opposite. The mechanism of accessing the market is held by insurance companies extracting margins out of services,” says Laraki. “If you show up with a better mousetrap, you don’t have an open liquid market to compete in. You still have to break in and figure out how to force your way.”

This is where you’ll want to get creative. Say the buyer in the default marketplace (insurers in Color’s case) doesn’t offer the right purchasing model for you to compete in, so you might need to go upstream or downstream to figure out if there’s a market segment (like employers for Color) and rebundling model (like vertically integrated services) that crack open a wedge of opportunity.

Laraki thinks there are plenty of places for today’s founders to find these wedges in legacy market dynamics. “This is a very relevant pattern to think about in the AI era,” he says. “I see lots of companies going after the existing customers of old mousetraps with a better AI-driven mousetrap. Some of these will work. But I think some of the most interesting opportunities will come from companies that redraw the service boundaries in ways that we thought were impossible or impractical up until now.”