Most of us buy into a certain set of myths when it comes to feelings on the job. Even though emotions play a central role in our lives, we’re trained to check them at the door before we head into work. We hesitate before talking openly about the monstrous emotions that lurk beneath the surface at startups. We’re told to “follow your head, not your heart” when it comes to making career decisions.

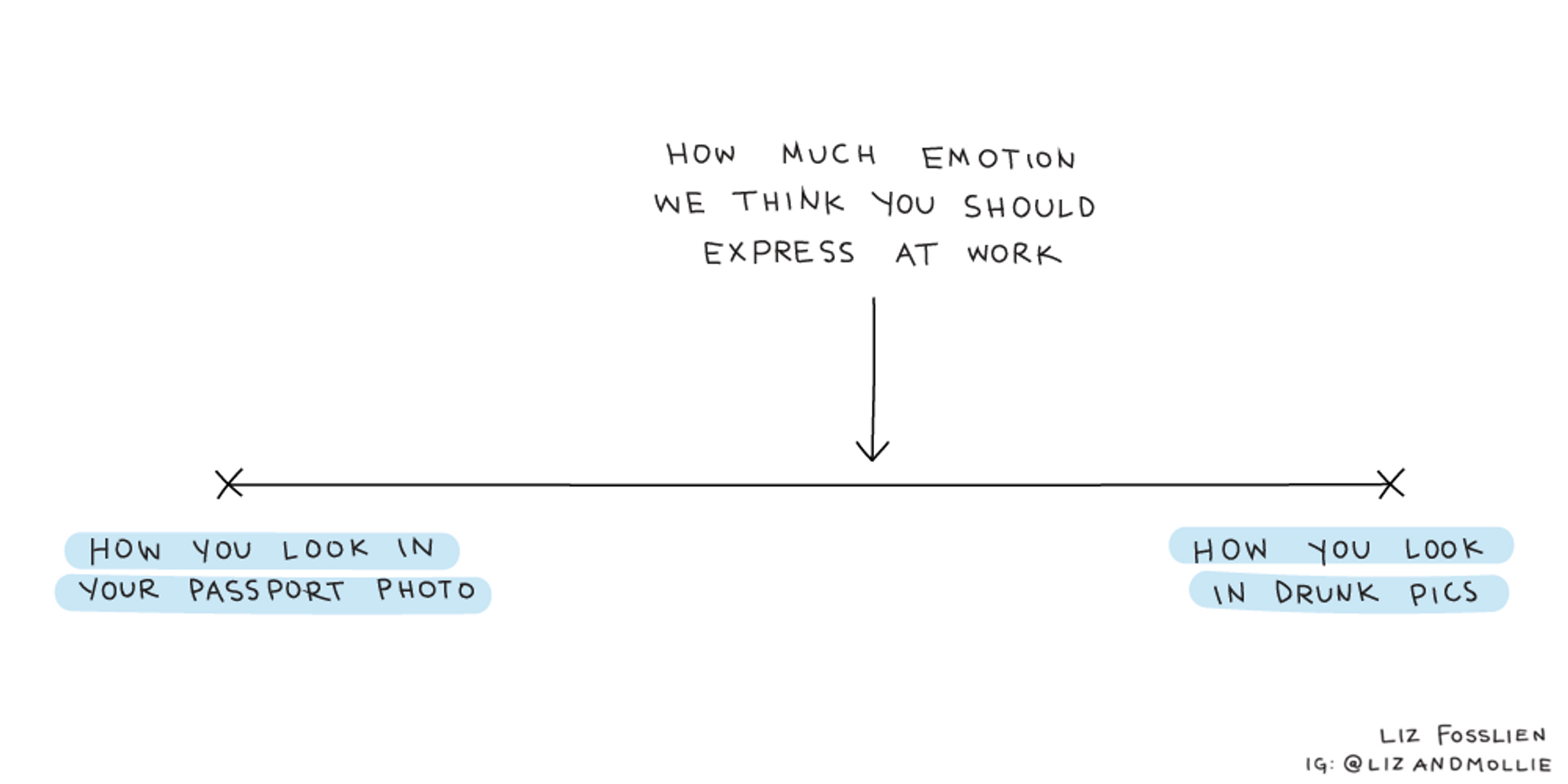

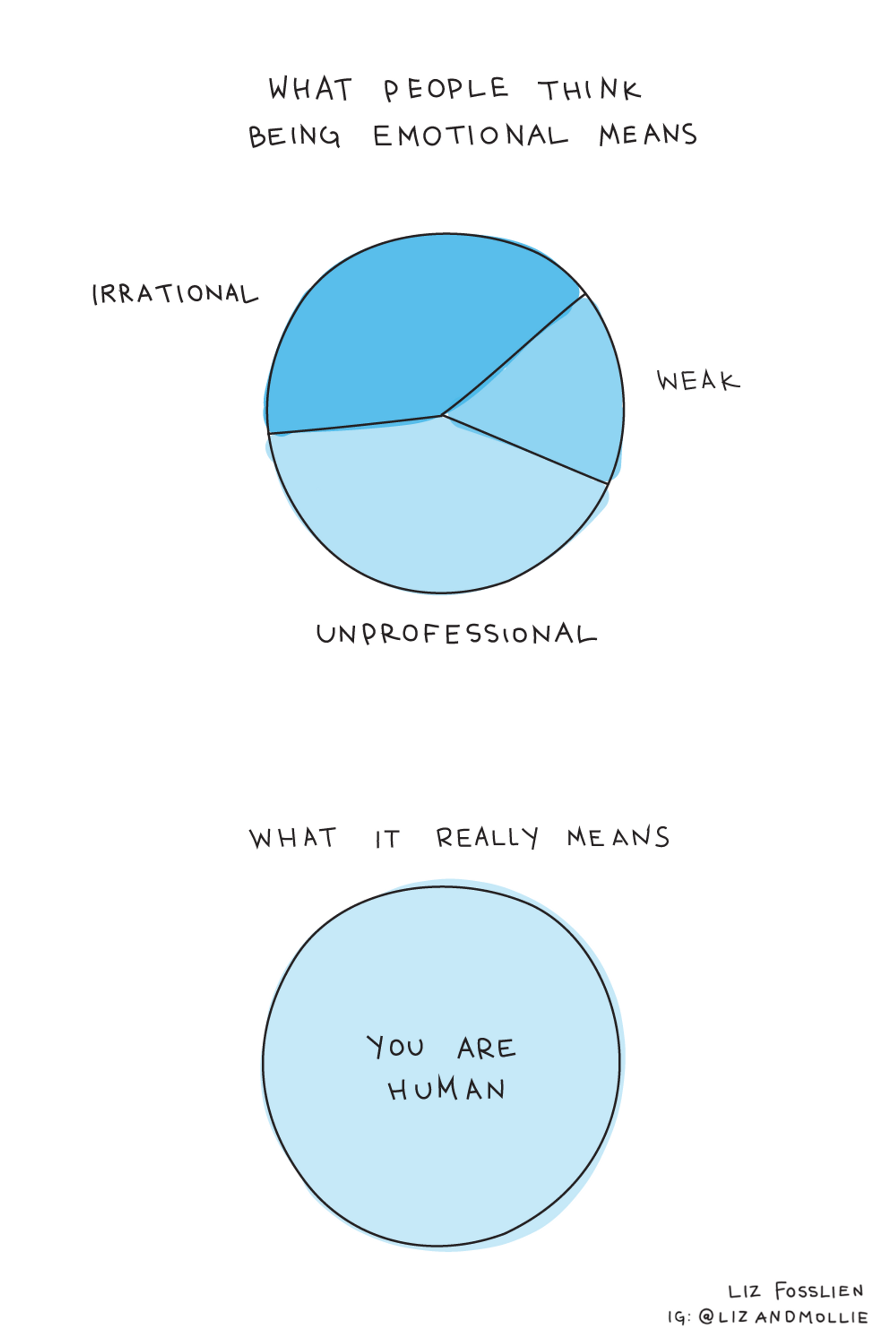

But in reality, the cost of ignoring emotions is steep. “Part of the reason why emotions have such a bad reputation is that we’ve tried to keep them out of the workplace for so long. We suppress everything we feel, which means we don’t resolve issues while they’re still manageable. Instead, our feelings fester. That means the only forms of emotional expression we see in the workplace are someone yelling at a report or breaking down in tears — these very intense, unproductive outbursts,” says Liz Fosslien, the current Head of Content at Humu and former Executive Editor at Genius. “This feeds a vicious cycle: we think, ‘Emotions are bad and scary, so we should shut them down’ which perpetuates the harmful myths around emotion.

Fosslien is here to correct that narrative. With a career trajectory at the intersection of economics and art, she’s uniquely positioned to offer a nuanced perspective on emotion and professional life: She started her career in economic consulting before making the leap to startups. At the same time, she’s handy with an ink pen, a published writer and illustrator whose artwork has appeared in places like The New York Times.

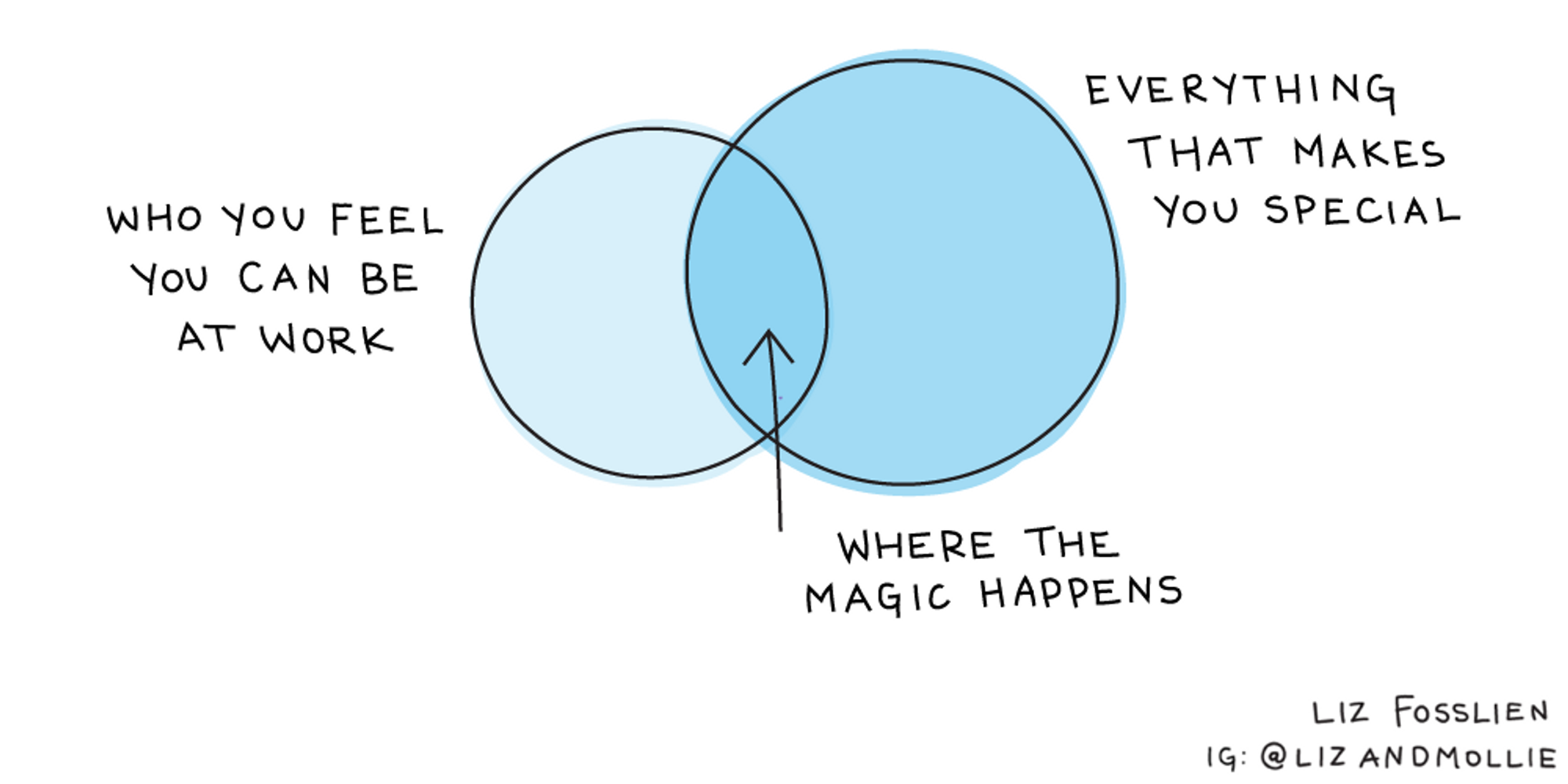

This year, she and her co-author Mollie West Duffy published No Hard Feelings: The Secret Power of Embracing Emotions at Work. Their book weaves together advice from researchers and executives across industries, from Wharton professor Adam Grant to Radical Candor author Kim Scott. The advice is threaded through with Fosslien’s witty, original illustrations — think a doodle of The Little Engine that Literally Could Not Even, or different types of feedback depicted as cookies. (Beware the frosted sugar cookie: it’s “overly sweet and ultimately unfulfilling.”) Taken together, the book is a roadmap that helps employees circumnavigate the misconceptions around emotions at work and set a course for healthier, more compassionate waters.

“The truth is that being in tune with your emotions makes you smarter overall,” says Fosslien, who has given talks about emotions-at-work at SXSW, Viacom and Google. “Being aware of emotions, and the signals they contain, can be an enormous strength.”

Everyone wants to make work better. We spend so much time here. Why wouldn’t we make it a place where people can be themselves, a place where other people are happy to be there, too?

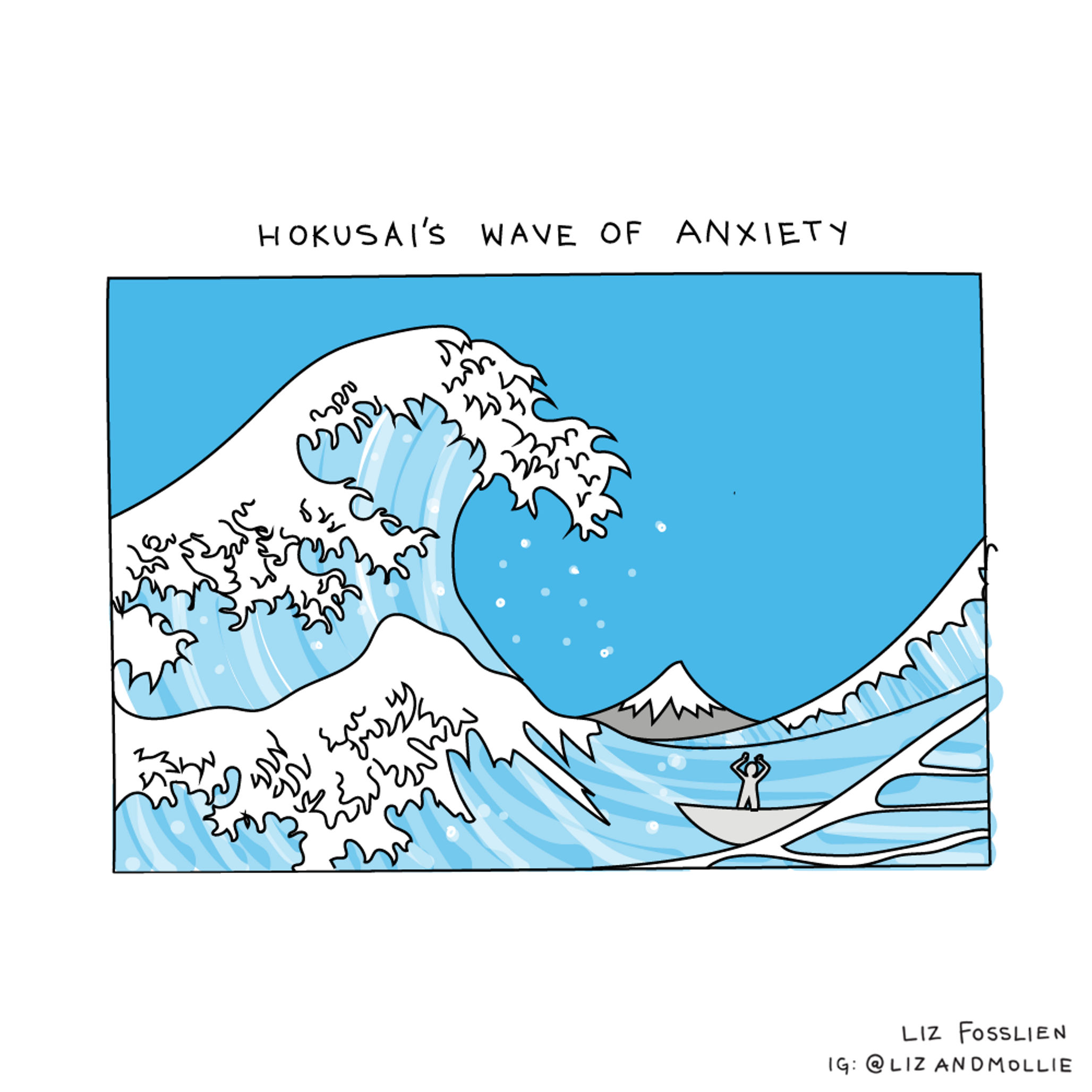

In this exclusive interview, Fosslien walks us through the seven emotions that we all deal with (and try to push away) at work: Anxiety, Envy, Uncertainty, Conflict, Spiraling, Not Belonging, and Rejection. She weaves in stories of how those emotions have played a role throughout her career, from her anxiety-ridden days as a young analyst, to her multifaceted career as an artist, writer and head of content. Drawing from her book and new commentary, she provides tactics to help individuals and managers not only work through each emotion, but to embrace them as career signposts and hidden superpowers.

1. ANXIETY

By the time that Fosslien took a consulting job after college, she had already internalized the need to suppress anxiety at work. “Especially as a woman in the workplace for the first time, I was trying to live up to this idealized image of the ‘consummate professional.’ Even though I was constantly anxious, I felt the need to keep my head down, agree to take on more work and hide all of my stress and unhappiness under a veneer of calm,” she says.

Fosslien knew that ignoring her anxiety was taking a toll on her health and personal life. “Like many young people starting their careers, I thought that the key to success was checking your emotions at the door and paying your dues — which meant working and working and working,” says Fosslien.

In other words, Fosslien was becoming what she calls a work martyr. In pressure-cooker workplaces, employees feel the need to prove themselves by staying late and working through weekends, all while quietly suffering anxiety and its insidious side effects.

“Work martyrdom is especially prevalent in startups, where the pace is intense.That intensity is really useful occasionally, but you can’t sustain it, and I think that’s why we tend to see so much turnover,” says Fosslien. “Founders also say things like, ‘We’re a family.’ That kind of messaging can create cohesion, but it also puts disproportionate pressure on employees to constantly go the extra mile, even when it compromises their well-being.”

An expectation of constant intensity and messaging like “we’re a family” are both examples of signals that set a workplace’s emotion norms. From startups to large companies, unhealthy emotion norms can not only create anxiety, but also discourage people, like young Fosslien, from acknowledging and working through it.

“If you go to your manager to try to talk about how you’re experiencing work, and she shuts the conversation down, that’s an explicit signal,” says Fosslien. “But most of the time, the signs we receive about the ‘rules’ of emotions and the workplace are far more subtle. For example, say someone at the office starts to cry. If the only reaction from colleagues and leadership is uncomfortable silence, that awkwardness signals that displaying emotion is not okay.”

Our discomfort with things like seeing someone cry at work speaks to the fact that we’re not emotionally fluent. If we keep treating emotions like a stigma instead of a reality, we’ll never learn how to compassionately resolve these situations.

Sometimes, negative emotion norms even lead us to normalize unhealthy forms of anxiety. “I once went to dinner with three female friends and one mentioned, ‘Everything’s going well at work, though lately I’ve been having terrible headaches, like my head will suddenly feel like it’s on fire.’ Another friend and I sympathized, ‘Ah that’s terrible. We’ve had similar issues.’ And then we just keep on chatting casually, until my third friend stopped us. She was horrified. ‘That is not normal. Feeling like your head is on fire shouldn’t just be an acceptable part of your workday.’ I didn’t think anything of it until my friend said that,” says Fosslien.

Although unhealthy emotion norms might have long reinforced suppressed anxiety and work martyrdom, Fosslien says that individuals and managers can navigate around (and push back against) the status quo. Here’s how:

Reframe “good enough”

Fosslien shares the following story from her book about how she was able to set a realistic perspective on her achievements: “I was organizing an event recently and I felt overwhelmed. Noticing I sounded stressed, one of the attendees, a career coach, asked me, ‘When will you know that you have done enough?’ The answer seemed obvious: ‘When I feel the event has gone well.’ She laughed. ‘How much of the event do you think you can control? I bet it’s less than 30 percent. What if a speaker gets sick or the caterer doesn't show up or it rains really heavily during the planned patio lunch?’ Enough has to be a metric that is within your control. For example, ‘By the end of the week, I’ll have sent the program designs to the printer.’”

“Enough” can’t be “When I feel good,” because feeling good is a moving target.

Get anxiety out of your head — put it on paper instead

Sit down and take 15 minutes to make a list of everything that’s causing you stress. Then, triage your stressors. “There are ‘withins’ and ‘beyonds.’ ’Withins’ are issues that you can act on,” she says. “They can be broken down into micro-steps. Say you’re worried about a presentation. If you think ‘I need to make the slides for my presentation,’ you’re going to be even more stressed. Instead, say, ‘Today, I’m going to make the first two slides.’ You’ll feel much more motivated by a series of small wins.”

But what to do about the pesky “beyonds,”the stressors you can’t do much to resolve? “Unfortunately, you can’t fire a bad boss. But you can find ways to limit your interactions with your boss,” she says. Fosslien shares a story from Bob Sutton’s The No Asshole Rule, about a doctoral student who would get a daily barrage of emails from her advisor. Instead of scrambling to answer them one by one, the student decided to wait until all the emails came in, then write a single email that responded to all of them. “That was her small, but effective way of containing the deluge,” says Fosslien.

Take anxiety as a signal to shape your future

“When you’re distracted by anxiety, you risk succumbing to burnout. You’re unable to think past surviving the next week, and you’re far less likely to dream big about your future because you’re this burnt-out husk of a person,” says Fosslien. Instead of letting anxiety cloud your inspiration, use it to forge a way forward.

“Pay close attention to moments when you’re not as anxious,” says Fosslien. “If there’s a part of your workday or a project that you always look forward to, whether that’s getting lost in a spreadsheet or drafting a newsletter, write it down.”

Take notice of the moments that give you lightness. They’re the lanterns on the path away from anxiety.

Then, initiate a constructive conversation with your manager, and bring your data. “Point to the tasks that give you energy,” says Fosslien. “Tell your manager, ‘I think these are my strengths. How can I shift my responsibilities to do more of the work that plays to those strengths?’”

It’s especially important for those early in their careers to manage their anxieties with an eye toward their future career goals. Fosslien has this advice to share with the young and the anxious: “Prove yourself, but don’t forget to listen to yourself. Part of the reason people become work martyrs is that we’re told to find work that we’re passionate about, and give that work 110%. But if you’re young, it’s hard to know right off the bat what you’re passionate about. Your first job should be as much about you proving yourself as about you understanding yourself, getting a better idea of your strengths and how you can prove yourself in an arena that you love later on.”

2. ENVY

Since envy is typically considered a negative emotion (and it even has top-seven spot on another infamous list), most of us try to stamp it out whenever it threatens to flame up. “Jealousy is stigmatized, especially among women, because of the stereotype that women are ‘catty.’ So we often perform mental gymnastics to convince ourselves we’re not jealous,” says Fosslien. “If you take the time to observe your envy, though, it can tell you a lot about what you want.”

Fosslien shares the story of Gretchen Rubin, the researcher, podcast host and author of The Happiness Project and The Four Tendencies. “While Rubin enjoyed a successful career as a lawyer, she noticed that her envy pointed her elsewhere: When she read stories about accomplished lawyers, she felt good, but not great. But when she read about accomplished writers, she felt physically sick with envy. Her envy signaled what she wanted most. It was a clue that she needed to move her career toward that direction,” says Fosslien.

As Fosslien struggled in her early days as a consultant, she experienced jealousy of other people’s happiness. “I remember being wildly jealous of people who were happy to go to work, who seemed excited about what they did. I did not feel that way, and I suspected that I wouldn’t if I stayed there,” she says. Her green-eyed monster was her green light to go somewhere else.

Close the gap between envy and reality

Here’s an exercise that Fosslien recommends to get you attuned to your own green-eyed monster: “Look into your network. Think about four people’s careers, then ask yourself: Whose career am I most envious of?” she says. “Break down their career path: What’s the first step you could take to bring yourself closer to what you envy?”

When you’re struck with career envy, don’t push it down — observe it. What does that other person have that you wish you had? What steps can you take in that direction, to become a version of yourself that you’d be jealous of?

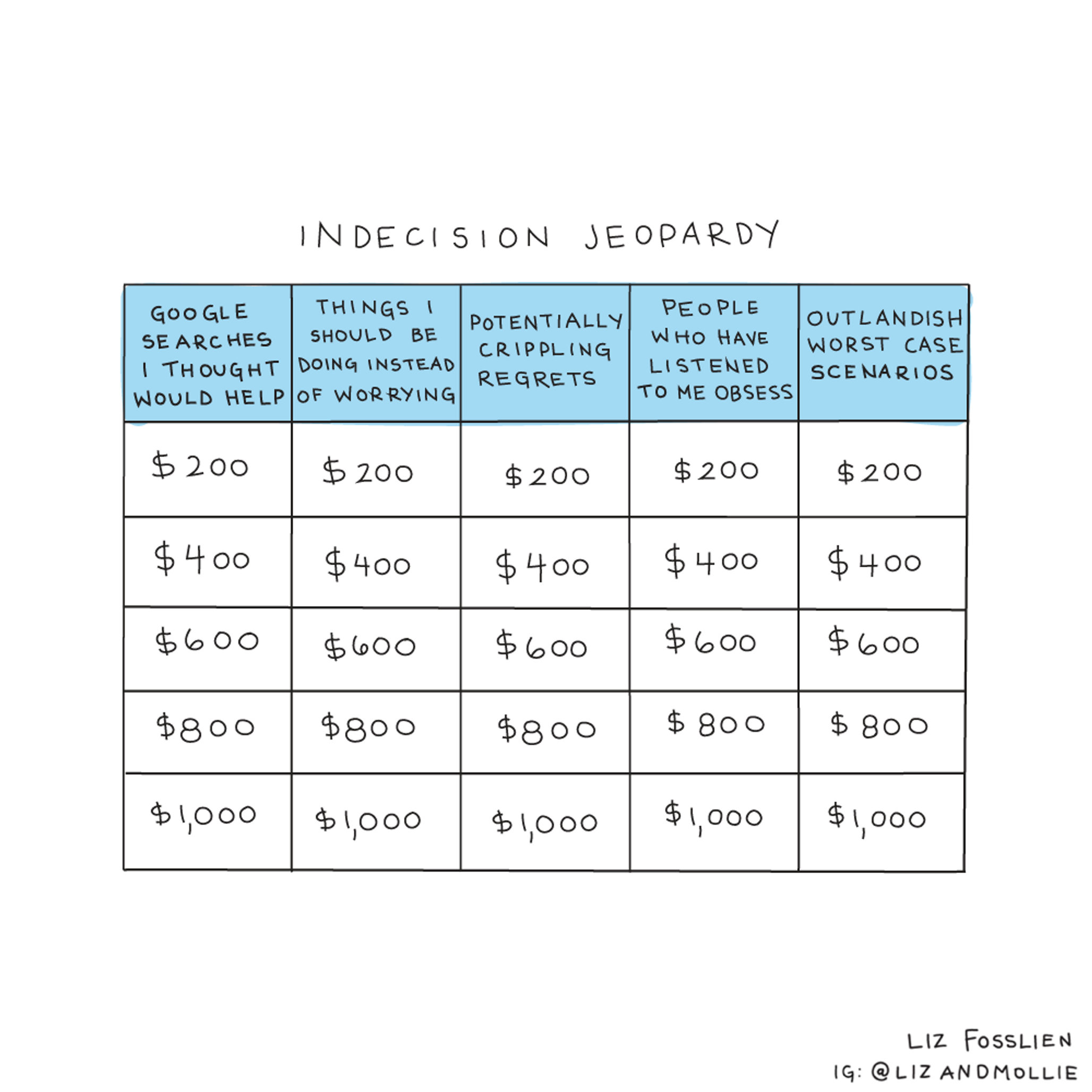

3. UNCERTAINTY

With her anxiety at work hitting new highs and her envy tugging her elsewhere, Fosslien acted on her emotions: She quit her consultant job, without another prospect lined up. To make ends meet in the meantime, she worked at Starbucks.

“I needed to hit the reset button,” she says. “I don’t necessarily recommend quitting without another gig lined up; it’s hard and scary, and it’s always better to look for a different job while you’re still employed. I was lucky that I had some money saved up, so I could afford to leave without a plan,” she says. “And I ended up learning a lot about design and creating customer relationships while working at Starbucks. Again, I don’t recommend quitting impulsively, though I do think people should be unafraid to start looking to leave a job that truly isn’t right and to find other opportunities to learn.”

If there’s a role you’re excited and curious about, but you don’t know how it “fits” into your career path yet, just do it. Especially early in your career, embrace the leaps that don’t make sense yet.

Even so, fear and uncertainty were constant, unwelcome companions on this segment of Fosslien’s journey. She couldn’t be sure that she was doing the right or best thing, or what her next move would look like.

After interviewing for her next move and landing an offer from Genius, Fosslien felt the grip of uncertainty on her again. “Back then, Genius was still a young startup. Joining while everything was so unpredictable would require an enormous leap of faith,” she says. “I couldn’t decide if I wanted to accept the offer or not. At first, I tried to be really rational about it.”

Logic seemed like the obvious weapon of choice for Fosslien, a self-professed econ nerd. (Her academic background is in mathematical economics, and she admits to reading abstracts for fun.) But as much as she tried to apply her analytical economist’s lens to the problem, her calculations were constantly stymied by the unexpected variable of emotion. “On paper, it wasn’t clear yet that this would be a good move for me,” says Fosslien. “But when I really thought about it, the idea of not taking the offer filled me with regret. I thought the product was fascinating. The people were smart. They were engaged in a way that I was not when I was a consultant.”

As she took a closer look at her emotional temperature, she noticed her excitement was mixed with anxiety. “I realized the anxiety didn’t come from external stressors, like fears about the unpredictability of the startup. It came from me, worrying if I could handle this responsibility — and that’s a form of anxiety you can power through. I answered my anxiety and said, ‘I am good enough.’ And I took the job.”

Add clarity to uncertainty with a decision-making checklist

In their book, Fosslien and Duffy provide a checklist to help add structure to the void of uncertainty:

- Write out your options. If you’ve written down only two things, take a moment to see if you can introduce an additional alternative. Choices usually aren’t binary. When you limit your decision to yes or no, or A or B, you make the stakes much higher than they might actually be. So if you’ve listed “Stay at my current job” and “Take the new job,” think about whether you could broaden your menu by adding something like, “Stay at my current job and ask for a promotion.”

- List everything you’re feeling, and link the remaining relevant emotions to specific options. Are you irritated? Afraid? Craving caffeine? Notice if a feeling is tied to a single choice. Are you most excited when you imagine yourself picking Option A? Are you afraid you’ll regret choosing Option B?

- Ask what, not why. Compare “Why are you afraid?” to “What are you afraid of?” You can easily answer the first question with a self-pitying platitude (“Because I never try anything new”), but the second forces you to address your specific feelings about the decision at hand.

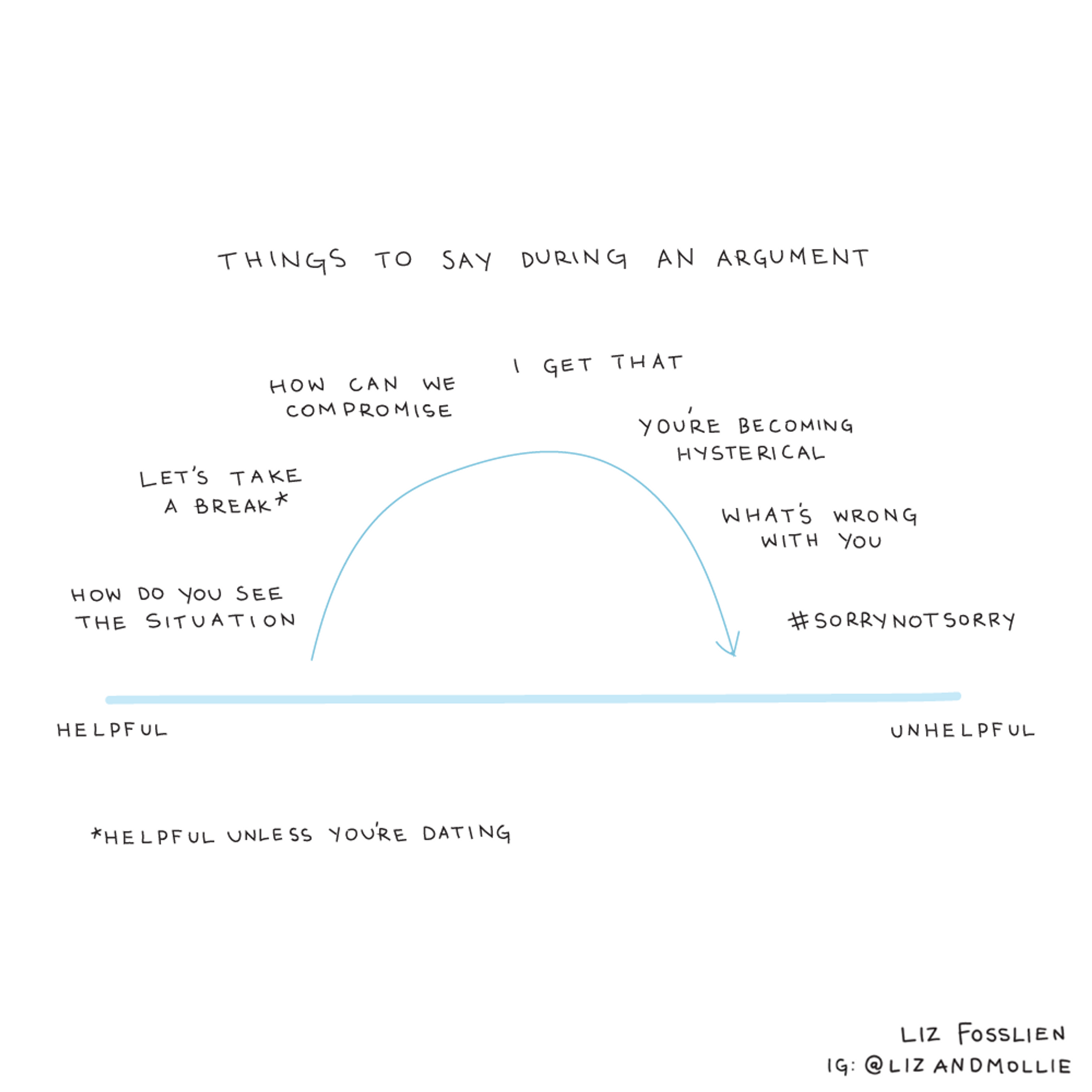

4. CONFLICT

Most of us have had those days: You and your manager just can’t agree. You and your team are locking horns. When conflict at work seems irresolvable, and negative emotions are boiling over, you might think that your only option is to quit immediately and slam the door on the way out. But don’t rage-quit just yet — there’s another way through it.

“We don’t often slow down and spend time on relationships in intense startups environments, so conflict becomes magnified,” she says. “If we take the time to form relationships and better understand each other’s work styles, we can avoid a lot of misunderstanding and grief.”

If your startup’s task is to grow and scale and make your product the best it can be, why wouldn’t you apply that same urgency to investing in good relationships at work?

Confront conflict without setting fires

You shouldn’t suppress or ignore your emotions, but you also don’t want to be a feelings firehose. “Startup settings are the most volatile when it comes to confronting conflict,” says Fosslien. “Make sure the embers of rage have died down some before you breach the conversation.”

Fosslien makes an important distinction between talking about your emotions and getting emotional. She shares her best principles for using words (and other strategies) to approach conflicts at work:

- Make an observation, not a generalization. A colleague interrupts you at a meeting. “You could say, ‘Hey, you’re rude,’ but that’s going to be interpreted as an attack on their character,” says Fosslien. “Instead, be specific and constructive: ‘You interrupted me in that meeting. It made me feel like I wasn’t a valuable part of the team. I’d appreciate it if you let me finish speaking next time.’ There’s a path forward from that criticism.”

- Walk it off before walking back in. “My co-author Mollie and I hate the advice ‘never go to bed angry.’ Go to bed angry! Negative emotions, like jealousy or frustration, skew your view on reality,” says Fosslien. "If you know you’re going to have a difficult conversation, take a five-minute walk beforehand. You might think you’re too busy, but those minutes aren’t going to make or break your company — a public outburst, however, could have far-reaching consequences.”

For managers: Freeze rage-quitting in its tracks

When Fosslien interviewed author and Wharton organizational psychologist Adam Grant, he clued her into a potential root cause of rage-quitting. While Grant’s work on leadership has been prolific, the question he is asked the most is about followership.

“People were constantly asking him, ‘How do I get my manager to hear me?’” says Fosslien. “I think that’s where rage-quitting comes from: people who are in the weeds of a project, surfacing problems to their higher-ups, but not being taken seriously,” she says.

The best managers ask questions and invite specific, meaningful feedback. Ask your direct reports, “What is one thing I can do to improve? Or “ Is there a roadblock I can remove for you?” she says. Finally, if you ask for feedback, follow through on it. “If your direct reports give you feedback and then get radio silence in return, they’re never going to give you feedback again,” says Fosslien. “Showing that you will take action on feedback is the best way to create a culture in which people feel valued speaking up, rather than like their only choice is to flip out on you and leave,” says Fosslien.

5. SPIRALING

Sometimes, negative emotions start out as a tiny, irrelevant irritations. Left unchecked, though, they can fester and infect relationships. Fosslien calls them “grump spirals” — and they are, unfortunately, contagious.

“If you catch yourself thinking these extreme words, like always, never, catastrophe, it’s usually an indication that you’re stuck in a negative thought spiral that’s making you blow a situation out of proportion,” she says.

It’s a good idea to recognize a grump spiral before it becomes a whirlpool that pulls you underwater. “After you make a mistake — say, you sent an error in a mass email — don’t think, ‘I always mess things up, I’m a horrible person.’ Instead, say, ‘I’ll be more careful next time, and will use this as a chance to show improvement in the future.’”

In their book, Fosslien and Duffy created a step-by-step guide to untangling yourself from a spiral, using the example of what to do when one of your team members suggests a big change right before a deadline

- Notice difficult emotions. Instead of snapping at your coworker in annoyance, pause and observe the feeling.

- Label each emotion. The ability to describe complex feelings, to distinguish awesome from happy, content, or thrilled, is called emotional granularity. Emotional granularity is linked with better emotional regulation and a lower likelihood to become vindictive when stressed. With emotional granularity on the team project, you’ll be able to realize that by “I’m feeling annoyed,” you really mean “I’m worried that we won’t have time to make these changes.”

- Understand the need behind each emotion. Once you’ve labeled each emotion, flip your perspective and explicitly state what you’d like to be feeling instead. Ask yourself “What do I want to feel?” If you’d like to feel calm instead of anxious, figure out what you need to do to successfully relax. That might be ensuring stability: you want the project to stay on track.

- Express your needs. Don’t say, “I’m annoyed by this request for last-minute changes.” Try, “Your edits are good, but because we are down to the wire, stability and predictability are important. What edits do we have time for? How can we make this work?”

Fill up your smile file

“One great way to stop a spiral in its tracks is by loading up what I call a smile file,” says Fosslien. Screenshots of a funny Slack conversation, praise from colleagues, documentation of your work wins — all of this evidence of comfort and validation belongs in your smile file, which you can glance at whenever you need to pull yourself up out of a gloomy spiral.

For managers: Practice emotional check-ins before meetings

”When we were working on the book, Mollie and I talked to leadership advisor Anese Cavanaugh and picked up this micro-action for meetings: Get your team to rate their mood on a scale of zero to 10. If someone’s below a five, ask a few probing questions to see if there’s anything you can do to raise the number,” she says. “Is he feeling stressed about an email he needs to answer? Let him finish the email and come back, hopefully significantly less agitated.”

6. NOT BELONGING

“There’s so much conversation right now about making our diversity and inclusion less talk and more walk. Belonging is the key ingredient to making that happen. What can leaders do to help people feel valued? To feel like they can speak up in the workplace?” says Fosslien.

When Fosslien started at Humu, she noticed that the founders were attentive to the ways that company environment influenced a culture of belonging. “One thing that I admire about Humu is that we only have 40 employees, but we already have a dedicated mother’s room. That sends a strong, inclusive message,” she says.

Never underestimate the power of the small decisions that shape company culture. Whether you have a dedicated mother’s room, or a holiday policy that honors different faiths — or if you have neither — it sends a strong signal about what your startup values.

Even if you’re an early-stage startup with four employees, it’s never too early to make intentional decisions that shape culture. “Small choices on culture cast long shadows,” says Fosslien. “Look for opportunities to put policies into place that you might not even have to use yet, but that pave the way toward the company you want to build.”

While concepts like company culture can seem squishy and easy to dismiss, whether or not employees feel like they belong has a concrete effect on the bottom line. “When we were researching for the book, we found a study that analyzed the language that new employees used in emails,” says Fosslien. “It showed that new employees who don’t switch from ‘I’ to ‘we’ pronouns during the first six months of their jobs were more likely to leave.”

For managers: Underscore belonging

“I love Adam Grant’s tactic for interviewees to learn about an organization’s culture: A job candidate can ask, ‘Tell me a story about something that would only happen here,’” she says. “It’s a neat trick for candidates, but when you’re a manager, and by consequence an arbiter of the company’s culture, you should be asking yourself that, too. What’s that story for your company? Does it involve people feeling included and heard? Think about what those potential answers signal about your startup’s culture of belonging.”

Fosslien also makes the case for having belonging interventions. “They’re short meetings where, at the beginning of a new job, a manager says to a new hire, ‘Hey, starting a new job is hard. It’s a scary and uncertain process for most people. You’re not alone, and you’ll be fine.’”

Humu’s CEO, Laszlo Bock held a similar intervention when Fosslien was new to the company. “He met with the four people who started in the last month and told us, ‘The first months at any job are often a lot to take in, but you can feel confident. Ask questions, get to know everyone, and don’t be anxious if you still feel you have a lot to learn at week two. You were hired for a reason, and we’re glad you’re here.’”

7. REJECTION

In 2014, Fosslien started working on a side hustle to fuel her creative side: a little volume of her sketches and gathered career wisdom that eventually turned into her bestseller, No Hard Feelings.

As someone who has pitched creative work in the past, Fosslien’s no stranger to the looming fear of rejection. It’s the black cloud of doubt that threatens to topple not only the work that you’re proud of, but your sense of accomplishment. And when rejection does rear its ugly head, particularly when it upends something that you care deeply about, it can be hard to recover from the blow.

But consider the flip side of rejection: “There’s a rush of emotions you feel when you make that leap. Instead of letting the fear of rejection hold you back, let the possibility motivate you,” says Fosslien.

She offers tactics for pushing past the fetters of fear and embracing the promise of putting yourself out there.

Pitch yourself as a human being

As a low-stakes way to start making connections and publicize her work, Fosslien emailed three economics bloggers that she admired. “I approached them as someone who followed their work and was excited about economics. They ended up reposting my illustrations,” she says. Eventually, one of her projects, 14 Ways an Economist Says I Love You, was circulated among publications including The Financial Times and, of course, The Economist.

“Don’t be afraid to be honest about your admiration over email,” she says. “Open up by saying, ‘I love your work for X, Y, and Z reasons. I did this thing that I think you might like. If you enjoy it or want to repost it, I’d be thrilled,’” says Fosslien. “That’s it. Pitch yourself in a human way, and you’ll find that people will often respond to that authenticity.”

My advice for putting yourself out there is: Just send the email. Don’t overthink it. The best-case scenario is that it opens an amazing door for you. The worst thing that can happen is that nothing happens.

Share your works in progress

If you’re working on a personal project, you don’t have to toil away in solitude and emerge, years later, with your one masterpiece. Share your sketches and doodles along the way, too.

“Whether you’re working on a side hustle or assembling a portfolio, take the smallest piece of output and put it online somewhere,” says Fosslien. “Or even document the process in a low-lift way with a blog, or photos.”

The benefit of leaving artifacts of your creative work is twofold: “First, you get the project outside of your own head, so you can process it a little more objectively. Second, you have physical evidence that you can share with others,” says Fosslien. “While I was working on the book, I’d sometimes show my partner semi-completed illustrations, both to get his feedback and for the little boost of motivation when the drawing made him laugh.”

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER: HARNESSING THESE SEVEN SUPERPOWERS AT WORK

It’s time to knock down the myth of the perpetually cool, collected professional. “We’re going to have feelings at work. It’s just a part of being human, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” says Fosslien. “The problem is, we’re trained to think that it’s bad to be feeling all these things. You think you need to suppress, suppress, suppress — but then you never let the emotions work themselves out. The key to managing your emotions isn’t ignoring them, it’s listening to them and practicing emotional self-care when you need to.”

Finally, when feelings like anxiety and envy sink in, remember that they’re not as unproductive as they might seem. “We evolved to have emotions. Many of them are useful cues. As it turns out, our emotions can sometimes tell us more about what we want than pure logic. Tapping into to them as strengths makes us better employees and happier humans in the end.”

Photography by Bonnie Rae Mills. Illustrations courtesy of Liz Fosslien.