If save-for-later service Pocket had a spirit animal, it’d be the American field ant. Like the insect, the startup supports that which is many times its own size. It serves its 20 million registered users — who have saved over 2 billion articles and videos for later — with a team of just 20 employees.

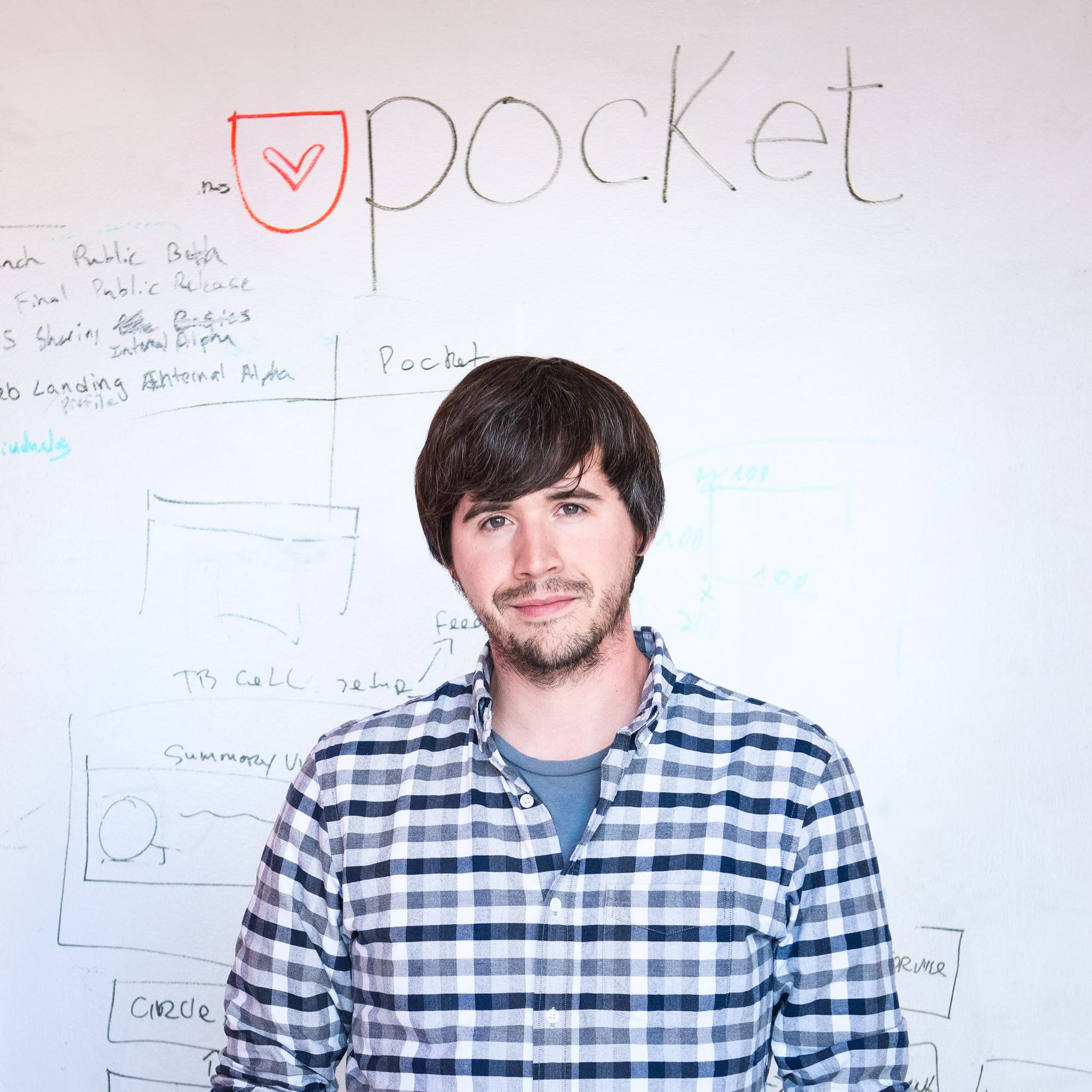

At the center of this supernatural ability and efficiency is founder and CEO Nate Weiner. Pocket just celebrated its eighth birthday — but for roughly half of the company’s existence, Weiner was the sole employee. On his own, he built and designed Pocket’s website, API, iPhone app and iPad app, and fielded support requests from his first few million users.

Pocket is proof that size of team doesn’t equal scale of impact. In this exclusive interview, Weiner explains why scaling a company doesn’t always mean increasing headcount (and burn). Instead, he shares the two ways startups can grow a business without a marketing or sales team, and the incredible advantages of staying small for focus, culture and trust. Any early-stage company that seeks to punch above its weight can benefit from Weiner’s exceptional (in more ways than one) experience with growth.

Nearly four years into Pocket, Weiner decided to raise money to turn his one-man-show into a team. How many people would he need? For someone who built the first version of Pocket on his own in a night, five people seemed like a lot. “I asked myself, ‘What the hell would five people do?’” Weiner says. “Evernote (which had made a bid to buy Pocket in its early, early days) employed around 60 people when I first started talking to them. I couldn’t fathom having a team that size. What would they work on? Why’s a team of ten working on what one person can do?”

Today, Pocket is in the process of moving into a new office to fit its now quickly growing team (targeted at two dozen by year-end), so it’s clear that success has shifted Weiner’s perspective, at least a little. Still, he maintains how Pocket’s sustained smaller size in its early years was formative to its long-standing winning streak. And even now, he doesn’t want any sudden moves to lose or dilute the very traits that got the company where it is today: focus and trust. Below, he shares how keeping a team small can be an invaluable guiding principle.

Force Focus with a Smaller Headcount — Either Real or Simulated

Management mantras harp on the importance of focus and staying nimble for startups. But they tend to leave practitioners to will clarity and agility into reality. Like any other startup, Pocket struggles with staying focused while prioritizing the many inbound or upcoming opportunities it’s always juggling. Unlike most companies, it views its small headcount as a means — not a limitation — to focus.

For the first quarter of this year, Pocket had over 20 projects on the docket across the entire company — that is, more projects than employees. “Focus is an enduring battle for a company of any size,” says Weiner. “If we were a larger company, we might’ve been tempted to elect a lead for each project, allocate engineers and push ahead on all fronts. But our limited resources prompt frequent reflection and rigorous prioritization.”

Pocket only completed one-fourth of its projects slated for the first quarter. With so much in motion, the team felt dispersed and directionless. “It didn't feel good,” says Weiner. “Then we got word of a marquee project: Mozilla wanted to build Pocket into every version of Firefox that people downloaded. That integration caused the entire company to focus on one thing. It took me back to the early days when we were just five people, and how we attacked one goal at a time with all of us behind it. We rallied together to do the integration quickly, all while furthering Pocket’s mission of giving more people access to the content they want for later enjoyment."

If you lead a small startup, ask yourself: restrictions aside, would I put the entire company behind this project? If the answer is yes, find a way to do it. “With everyone on the Firefox project, we moved so much faster, the quality of the product was way better and people were amped up,” says Weiner. “Then we went on to the next project — with more momentum, coordination and energy than if we decided to divide and conquer our list of projects.”

If you’re over 100 employees, find a way to manufacture the same scenario. Think back to the time when your company could fit into one room, and ask yourself if you’d put everyone on the project if you could. If the answer is yes, consider deploying more reinforcements from your current team. “Even at 20, 30 or even 50 people, you should really just be focused on that one thing that needs to happen right now,” says Weiner.

“I understand that bigger companies cannot shift the same way startups can, but it’s keeping that instinct sharp and active that’s key,” says Weiner. “Personally, I know I need that focus forced on me. The more people you add, the easier it is to keep doing what’s not critically important. With a smaller team, it’s very hard not to stay focused. You constantly need to avoid doing what you want to do in the future for that which has to be done now.”

For companies of any size, Weiner suggests putting the full team on the most critical project every quarter. “Over the next 90 days, what’s going to be the project that makes the difference? Let’s just make sure that we hit that goal the best we can and then we can move onto the next project.”

Pocket is now shortening its project runway to under 30 days — especially for engineering sprints. “I can tell you where we're going six months from now, but we try to focus a month at a time. A small team enables us to operate this way,” says Weiner.

Condense Your Culture But Expand Your Skillset

At larger companies, entire roles or departments are charged with defining and preserving culture in order to absorb hundreds of new hires. As Pocket’s sole employee for its early years, Weiner was both the only creator and custodian of its culture. While he knew he eventually needed more than one person to scale the company, he didn’t want to lose the drive and grit that had landed him early success.

With a small headcount, Weiner was able to keep Pocket’s culture concentrated during its formative years. This was possible because its culture wasn’t a fuzzy concept — it meant trust, scrappiness and ownership. Weiner had years to discover and refine founder-culture fit with the same rigor that most apply to find product-market fit for their companies. After all, there’s a saying in tech that 80% of your eventual culture is your founder (literally their personality traits).

Think stews not salads when it comes to company culture. Start by letting a few choice ingredients simmer together. Then taste. You’ll have a better palate for what it delivers and lacks than if you toss it all together from the start.

This hard-earned clarity allows Weiner to confidently hire in his image while gradually growing the team and diversifying its skillset. “As with all startups, at some point you realize you can’t do it all to completion or to a high standard. For example, I really needed help with design,” said Weiner. “Nikki, our Head of Design, was the first hire. I had the engineering and product experience, but she brought the design chops that we needed to truly make a great product. She changed the black and yellow color scheme — that had somehow looked good to me at the time — to what Pocket looks like today. It's been vital to bring on people who own and value their part of Pocket as much as I have from the start. They’ve made it better than I could have.”

Keeping Pocket around 20 employees has allowed Weiner to not only personally filter for those he can trust, but also assemble a group capable of making decisions and operating without him. With a small team, those bonds and common world view form more quickly without complex hierarchies in the way. “As a technical founder, engineering was the hardest area to let go,” says Weiner. “Early on though, I remember when it finally clicked: We had an issue with our back-end. I suggested an idea on how to resolve it. The team noted it, and then went to another room to sort it out. The solution that they came up with was way better than mine. It was a great moment to realize how it was okay to let go, and that it often turns out better when there’s acknowledged and mutual trust.”

A small startup can use its size to force focus and better preserve culture as it grows, but these benefits are just the fuel for the work the team has to do. Its output — the actual product — can also scale without increasing headcount, but only through two channels. “The only way a product can grow from a team of our size is if your platform carries you or your users carry you,” says Weiner.

The advantage of being small is that you find ways to make people outside of your walls part of your company.

Here’s how Pocket develops, ships and publicizes its product through its platform and with the help of its loyal users:

Here’s How Your Platform Can Carry You

In the early days, Weiner made it his goal to embed Pocket in every corner of the web. The intent was to create an “amazing consumption experience” for as many people as possible across all of their devices, which meant the app itself had to be extremely flexible and scalable.

Without a sales or marketing team, Pocket made its app as simple and straightforward for other companies to learn about and integrate its service — which, in turn, has exponentially grown Pocket’s users. To date, the company has tallied over 2,000 integrations, among them Firefox, Twitter, Flipboard, and Kobo.

With strong partner feedback and enthusiasm, Pocket now seeks to grow as fast as it can through its platform. Weiner sees tons of opportunities, but there’s more out there than Pocket could possibly build with its current team — even if headcount doubled instantly.

As a small, fast-growing company, you can go on a hiring spree or lean on your platform. If you opt for the latter, here’s Weiner’s advice:

Make it dead simple and low-lift. The team at Pocket relies on this question to make decisions: how can we make it simpler for all involved? For example, it’s now commonplace for startups to share their APIs, but Pocket takes it a step further. “Yes, the APIs that we build on as a company are the exact same APIs we give to every partner publicly. But can you help them with just a few lines of code?” asks Weiner.

Years ago, Weiner took on this challenge with the help of ShareKit, an open source Software Development Kit (SDK) that people could drop into their iOS apps. “I tried to make it literally one line of code for people to add Pocket and other popular services to what they were building.” says Weiner. “Companies could drop the line of code in and their app could share to any service like Twitter, Tumblr or Facebook. At the time, if you had to write the code from scratch on your own, it was weeks of work to set these things up. But I still wanted to make it simpler.” This is the same philosophy that guides Pocket today.

As much as possible, make it truly plug-and-play for others who want to build in your product. “If Twitter comes to us and wants to integrate Pocket, we’ve lost if it takes them a month to do it,” says Weiner. “They’re simply not going to do it. And I don’t blame them.”

Not requiring people to reinvent the wheel means first making sure what you’re working with is as simple as a wheel. If it is, they’ll use it and there won’t be much reinventing needed.

Structure integration as self-help.Pocket’s platform mentality has been a huge part of its growth. Allowing companies to build on its platform easily has been the first step, but scale happens when they can do so independently. “We’ve completed thousands of integrations without any business development — and the overwhelming majority without any support,” says Weiner.

Simplicity has made it easy for partners to integrate Pocket, but the startup’s size has made it a necessity. “The deals with Kobo and Firefox only happened because we made it easy for them to self-serve,” says Weiner. “At first, Kobo asked us to integrate Pocket in two months. If our team of a dozen people (at the time) had to build it from scratch, it would have never happened. But we said, ‘Here’s our API.' Kobo was able to integrate Pocket within 14 days.”

For integration, the ideal is when companies can incorporate Pocket without ever reaching out to Weiner or his team. Pocket has found that its users typically request other apps to integrate the save-for-later service, which is what prompts new companies to learn about Pocket. “We’ve heard a few times that the number one feature request for apps is integrating Pocket. When companies look into it, they’re happy to check the request off the list on their own,” says Weiner. “That’s how Facebook Paper integrated Pocket. I had nothing to do with that — I just found out one day.”

Woo big partners tenaciously with your platform, then keep them with transparency. Simple platform integration and self-service doesn’t mean that startups should go on autopilot. Pocket stays on the radar of strategic companies that it believes will benefit from its product. For example, the first time that Pocket reached out to Firefox it was still known as Read-it-Later. “We started as a Firefox extension and I was one of the extension app reviewers early on,” says Weiner. “We’ve built the type of culture where we share our story, data and updates early and along the way, so companies — from major content services to device manufacturers — understand what it’s like to be our partner from the beginning. We want them to truly know — and be able to point to proof — that we’re ready when they are. One day, it clicked and Mozilla called. It’s now fully integrated Pocket as the save-for-later service for its Firefox browser.”

Remember: getting an app or company on your platform marks the end of a deal, but the beginning of an official working relationship. For Pocket, channeling “generous transparency” is the way it retains its partners and continues to improve its product with such a small team. “We try to share knowledge as much as possible. We don’t try to hide anything. We tell Apple and Google what we’re seeing in the market when they’re working on their share sheets,” says Weiner. “As a result, it's made it really easy for us to actually start getting these deals done as people want to solve their save-for-later needs. They know who to turn to.”

The takeaway for lean startups is to construct a platform that can enable external parties to operate as extensions of your team: sales, engineering and business intelligence. In the case of Pocket, its platform is simple to integrate, built for self-service and brings with it an increasingly rich set of data, that when aggregated, benefits all its partnering companies. “What’s next is leveraging our user base. While we have a hundreds of companies integrating Pocket, we have millions of users,” says Weiner. “The question now is: how can we serve them and also help them carry us even further?”

Here’s How Your Users Can Carry You

“Think back to what it was like to watch television before DVR or streaming. Or what it felt like to hail a cab without Uber,” says Weiner. “Whenever you find a place that feels old, people get really passionate about it, because the new way has become so core to their experience and going back to the old way just feels broken. With Pocket, I think we’ve hit upon a very different way of using content on the web. We have users that, when they go into another app where they can’t save to Pocket, say, ‘Is this an ancient time? What’s going on here?’”

Small startups who have users expressing this degree of passion should not miss the opportunity to direct that energy from expression into creation for the benefit of the company. For Pocket, that’s meant getting users to lend a helping hand to product development. Here are the two ways that Pocket’s users are supporting its next generation of products.

Shift your Beta channel from delivery to conversation to co-creation. When Pocket started, its release philosophy was about pushing out an airtight product to its users. The team would perfect every pixel before launch. “At the beginning, Pocket was a very waterfall-like product,” says Weiner. “We would deliver big releases about once a year. We’d go underground for six months and build something big and then we'd launch it. The releases were well received, but we suspected we should have been getting more out of our process.’”

Yet, after product-market fit, perfect is not only the enemy of good, but of growth. “Pocket is known as a very well-designed experience and app,” says Weiner. “While we want to keep that up, our development debates shifted from every nitpicking detail to how we open up and solve growth problems. As a small team at a growing company, we needed to tap into our users as collaborators, not just as beneficiaries.”

There comes a point for every startup when you’ve got to decide between perfection and progression. The first is a stable characteristic and the second is a dynamic conversation. Choose wisely.

Off the bat, that means having more frequent interactions with users. Getting them involved in product development isn’t just about opening the floodgates — it requires restructuring the way your team works. Pocket has moved to a faster release cycle to have more touchpoints with its users. “We're moving to a much faster cadence. Our sprints are a few weeks long and we’re closing in on a five to six week release cycle. For the team, it’s a far cry — and a cultural shift — from trying to get everything perfect before the public sees it. Now, we know there are bugs in what we ship, but now we aren’t the only ones squashing them.”

This approach was especially critical to Pocket 6.0, a prototype that the company uses internally. The team estimated that a full, public-ready version would take nine months to put out. “We were delighted by the beta and didn’t want our limitations to delay our users from experiencing it, too,” says Weiner. “So we decided to break it all apart. We laid out the five to six different releases that’d strategically get us there over a six week release cycle. So far, it’s felt good to get it out there, even if it’s piece by piece. We're getting feedback and signal back really fast. We listen, respond and incorporate it all. We also ship at the same time so users know they’re being heard — they’re like our remote team."

If you have one arrow and you shoot and miss, you're screwed. If you can continually re-aim until you get to the target, that gives you a much better look at the bullseye.

Used correctly, a Beta channel can give your team great feedback and allow your users to direct the product. Even if you haven’t hired, you’ll feel like you have more manpower to hit milestones and additional insights into fast-moving markets. “After our last fundraise, we set a lot of important milestones, especially around getting additions to the platform built out,” says Weiner. “We know that we want to get them out there to validate and prove them in the market. The sooner that we can do that, the better. The beta channel’s the way forward for Pocket and the way in for our users.”

Use surveys to learn from "the PMs" among your users. From the beginning, Weiner was struck by the enthusiasm and loyalty of Pocket users. “Our users love this product. I'm always blown away by how avid and vocal our fans can be,” says Weiner. “We get emails all the time from people writing in to say, ‘Hey. I don't have a bug. I just wanted to tell you guys that you’re awesome.’”

To fully engage this type of fanbase, use tools to solicit and leverage their support. Pocket has used surveys to not only collect feedback but also to directly guide its product roadmap. “We’re actually just reviewing 600 responses from a survey that we put out in our beta version of Pocket,” says Weiner. “Our support team is having conversations with people directly inside the product. We’ve actually received more feedback than ever through this channel.”

Many startups use surveys as an engagement tool, and casually treat the results as a byproduct. Don’t just listen, really hear what’s being said and how. “I always remind the team to look past the basic gist of the results,” says Weiner.

When users give you feedback on an obstacle, they almost always give you an idea on how to solve it.

"They don’t just say, 'I hate that this is the case.' If you keep reading, they’ll often include, 'You should let me pin this or swipe it away.' It may not be the solution in the end, but it will better define the challenge, which gets you closer to a solution.”

For example, Pocket now has two tabs, “My List” and “Recommendations,” at the top of the app. Results from the survey indicated that people wanted to swipe between the two lists, but that many users couldn’t reach their finger all the way to the top. “That was insightful, but it was also just one solution,” says Weiner. “The other option may be a standard UI convention on iOS, where you can bring the tab bar down to the bottom. All of sudden now, that's within reach of your thumb. But then, you also have to think about Facebook or other places where the new functionality may not be discoverable for a lot of users and many will have the same problem. If you jump to the first, second or tenth solution, you’re missing the point of fully grasping the need of implementing swipeable tabs.”

Lastly, when running surveys, keep in mind these three tips from Weiner:

- Segment your users into buckets. Pocket has divided its user base into “casual,” “core,” and “inactive.” The team makes sure to send surveys to a group within each category to ensure they’re learning from a representative sample.

- Lower the bar for participation. Pocket makes sure its surveys are easy to complete, which means they are less than five minutes long. Oftentimes, they’re even shorter. For the most part, the team prefers releasing two-questions surveys frequently than a ten-question survey released occasionally.

- Drop in surveys at multiple junctures. Pocket continues to experiment with where and how it surveys users. Like most apps, there’s a send feedback button (in beta for Pocket) that is a passive channel. Or an email will capture those who may not open the app every day. Also, after five minutes of inactivity in the app, Pocket may pop up with a live chat and ask: “Hey. Everything OK?”

Using tools to engage users, like surveys and Beta channels, and creating easy, low-lift ways for partners to extend and build on your platform are ways to scale your company without growing your headcount. That’s how Pocket continues to deliver despite its size. However, now that Pocket’s partners and users are becoming more active in shaping the future, they’re also influencing the startup’s definition of success.

“Back before we raised money, I kept saying that save for later is a system-level feature that needs to built into browsers and operating systems. People told me that would never happen. Years later we’re built into Firefox,” says Weiner. “Our strategy has been to first create a way to capture anything you find and want to save — regardless of the app or service — and get embedded with the partners to make that universal. Then it’s to create an amazing set of tools to consume content. This has given us incredible insights on information consumption and, soon, how to solve its challenges. There’s always a next goal, but it’s the same question that drives us: How do we help people get all the great stuff that’s out there?”

The key for Pocket — or any startup — is to tackle a colossal and ambitious goal with leverage. “Right now, we really want to get our platform to scale even more and reach as many people as possible,” says Weiner. “We want them to not only enjoy what we create, but help us build it. If for each Pocket employee, there’s a hundred partners and millions of users to help, we’ll have the muscle to make it all happen.”