There’s a certain squishiness when it comes to defining product-market fit. Sure, there are metrics to track, benchmarks founders and product leads can rely on as signals that their idea is starting to gain traction. But before those markers are even in place, how do you know if an idea is viable enough to keep pursuing?

As we’ve heard from several founders, it’s easy to spot and feel exponential growth when it’s happening live. But what is slightly more challenging is figuring out when that growth will be sustained and signify product-market fit, rather than a burst in growth that will quickly lull.

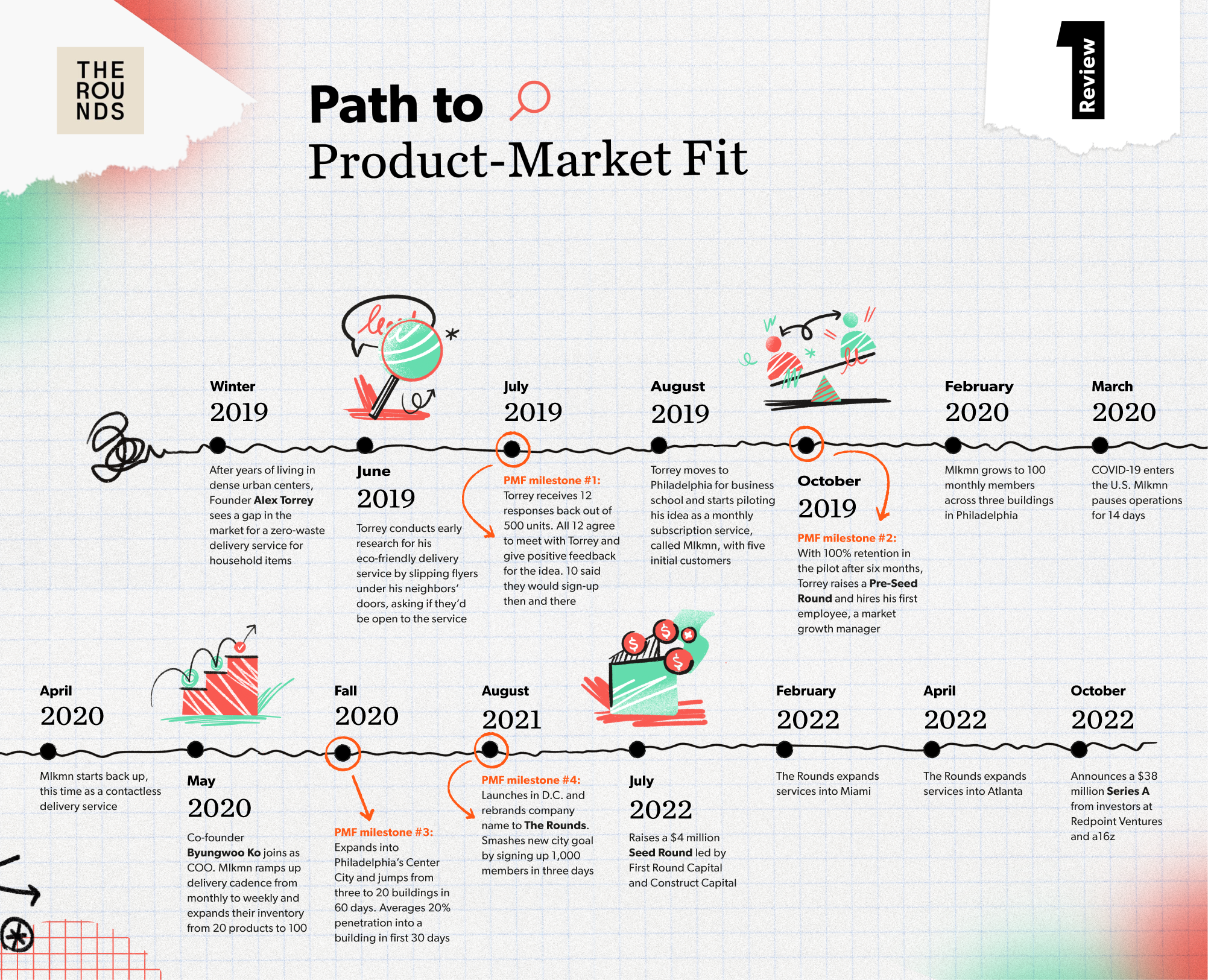

For second-time founder Alex Torrey, gut intuition, personal experience from his last startup and anecdotal evidence became the product-market guideposts he depended on to keep going. These markers helped assure him that he was gearing up for sustained growth rather than just a flash in the pan.

Torrey started the eco-friendly delivery startup The Rounds in 2019, right on the cusp of COVID-19 drastically shifting consumer shopping habits and increasing demand for home delivery. The service was born out of Torrey’s frustrations with a lack of sustainable options for getting basic household items like soap or toilet paper while living in city centers without a car. The Rounds caters to folks in similar situations, enabling customers to order household items and pantry staples on a recurring basis that are delivered to their door — with as little waste as possible.

The company announced its $38 million Series A in October 2022 and has expanded from its first market of Philadelphia into three other U.S. cities: D.C., Miami and Atlanta. The Rounds counts thousands of monthly users on its subscription service in each market and offers 250+ essentials across national brand, private label and local products in categories like household, pantry, personal care, dry goods and local favorites.

There are plenty of lessons to be found by examining how late-stage companies and tech unicorns achieved product-market fit. But it’s also well worth studying earlier-stage startups that are in the throes of their product-market fit journey — when the exact details of how they acquired customers are crisp in the founder’s memory.

So let’s rewind the clock to the very beginning of Torrey’s founder journey building The Rounds.

EXPLORING IDEAS

In 2019, Alex Torrey was a begrudging adopter of online delivery.

For the past decade, Torrey had lived in high-rise apartments smack in the middle of big cities, and his favorite part of his lifestyle was that he didn’t need to own a car.

“I’ve always seen it as a luxury to not own a car,” Torrey says. “But for a car-less lifestyle (which is growing in popularity), it’s a complete pain in the ass to get the most basic, boring products.”

The way he saw it, there were two options for carless city-dwellers to stock up on their essential household items — and each brought its own unique set of challenges. The first was the laborious task of walking or biking outside to the store and lugging back as much as you can carry to your apartment.

“When I lived in Chicago, I would put on my giant snow boots and jacket to go out to the restaurant to pick up my takeout or buy what I needed at the grocery store and bring it back in the middle of winter,” Torrey says. “Every time I would think, ‘man this stuff is heavy.’ Household items are bulky. I only had two tote bags, so I could never bring home a full haul and I was always making multiple trips to the store.”

To get around this pain point, the obvious move to Torrey was just to order what he needed online. But that also didn’t provide a great solution.

“If I ran out of hand soap and wanted to buy more, I would have an empty plastic bottle that would take hundreds of years to break down, yet its purpose lasted for probably 90 days,” Torrey says. “But I went on Amazon to re-order the same product, and the next day it shows up in a box the size of my kitchen table within another box. Then, I was holding two identical bottles of hand soap in plastic bottles and all the packaging waste — and I thought, ‘this makes no sense.’”

Surrounded by other high-rises, Torrey knew he certainly wasn’t alone in this.

“You do the quick math. If there are 500 units in my building, and there are five other identical buildings I can see just from where I live, and we’re all getting hand soap, and we’re all getting an individual box within a box, that’s 2,500 single-use plastic bottles of hand soap and 5,000 cardboard boxes,” he says.

That’s when he realized that there could potentially be a huge delivery market around sustainable convenience. The timing for this particular lightbulb moment was just about perfect. At this point in time, Torrey was gearing up to move to Philadelphia for business school and was itching to build another startup after winding down his previous company a couple of years prior. (His previous venture was clothing startup Umano, which he started out of his parent’s garage in 2013 and by 2015 negotiated a deal with Mark Cuban and Lori Grenier on ABC’s “Shark Tank.”) He wanted to take advantage of this life transition to go into full idea research mode.

I thought to myself, ‘How can I solve for an easier, more convenient way to get the most basic, boring essentials delivered to millions of people with zero packaging waste?’ That was the entry point for me to see what I could figure out.

Armed with personal anecdotes and a strong hypothesis, Torrey got to work to collect quantifiable evidence that there were others like him who wanted a similar solution.

Validating the problem

Torrey’s first instinct was to approach his building manager. As far as Torrey knew, there wasn’t a delivery service out there solving for sustainability and convenience at the same time, for both consumers and the delivery folks handling packages.

“I asked if I could advertise a service where I could create a schedule for refilling people’s household items (like hand soap) and bring it directly to their doors. There was no company at this point, I was just trying to figure out if there was even demand.”

Torrey also made sure to present this idea as a solution that would make lives easier for building managers.

“I pitched the idea from my point of view as a resident. I pointed out that the package room is overflowing. I don’t like going in there, I assume other residents don’t like going in there, and maybe most importantly, I assume you as the building manager don’t like organizing the package room,” Torrey says. “If I coordinate a way to buy and deliver refillable products to everyone in the building, would you be interested in promoting this service? I remember him getting really excited and giving me the go-ahead. ‘Anything you can do to help me get fewer packages,’ he said.”

When somebody has an out-of-the-ordinary reaction to something you are doing, either positive or negative, that’s where the juiciest nuggets are. That means you are onto something.

With the green light to advertise to other residents in his building, Torrey didn’t waste any time. To gauge the temperature of resident interest, he created flyers asking to meet with people and slipped them under every single door.

“The flyers explained a potential business concept for a community ‘group buying’ program. I broke down how it would work and how we can all benefit from buying these essential products together. It wasn’t a promo asking people to sign-up for their first delivery for free or anything like. I just wanted to know — would people be willing to sit down and talk with me about this idea?”

Out of 500 units, Torrey got just 12 responses back from residents who agreed to meet with him. “Not a huge hit rate, and if you think about it, a lot of founders would’ve taken that as a negative signal,” Torrey says. “But for me, it was all about the physical reactions I got when I explained to people “what if I told you that when you go to the store you don’t have to worry about these 20 products because they’d always be stocked in your home like magic?” were so motivating. Ten of the 12 people said they would sign up right now. It gave me the conviction to dig deeper,” he says.

BUILDING THE EARLY PRODUCT

With a dose of confidence from early conversations with the residents and managers in his building, Torrey started piloting his idea under the brand name “Mlkmn,” an ode to milkman deliveries from the early 20th century.

It was admittedly low-tech in the earliest days. “I created a signup system on a whiteboard I hung on the outside of my own apartment door and made up a fake name so that it'd look like at least one neighbor had already signed up,” Torrey says. “I also started outreach to a few other buildings on my block and was able to sign-up five paying customers.”

For the first six months, Torrey was on his own, which meant improvising on a minimum viable product.

“Customers were texting me directly to order products,” Torrey says. “I'd send a screenshot of an image that had info like the price and some basic product details like "hand soap (compare to Mrs. Meyer's)." It was actually Mrs. Meyer's, but it was in our own then-Mlkmn branded reusable container. I'd send an invoice via Paypal once a month and then V2 of the product was a Google Sheet, which we used for a long time before building any kind of digital product MVP.”

The mission was to be sustainable for the planet, yet more convenient for the customer. Torrey was going up against delivery behemoths like Amazon and DoorDash, who had quite the head start in building out teams of delivery drivers and fulfillment centers.

Torrey’s business model was simple. To cut costs, he would buy household items in bulk (like Mrs. Meyer’s hand soap) and sell them through his own service with custom-made Mlkmn labels. The catch was this was a one-time buy. Torrey continued to pick up and refill the original bottles to keep his service sustainable. He would then travel by bike to every apartment building in his radius and personally drop off monthly refills in people’s homes — collecting people’s old Mlkmn containers, cleaning and reusing them for refills.

I watched people’s eyes light up when they realized they could sit on the couch and have a fresh roll of paper towels replace the sad little cardboard tube left on their counter, without lifting a finger.

As the weeks went by, Torrey started to collect more and more that there was real market demand for this sustainable delivery alternative and that there was plenty of green space for his business to grow. Here are some of the early signs that made him realize his idea had legs:

- Customer love: “I’d receive dozens of personal notes saying ‘Thanks Mlkmn!’ ahead of their scheduled refills,” Torrey says. “That told me there was a real anticipation for the day I came to refill their stuff — it brought this unique element of interaction and engagement.”

- Customer leniency: Despite some operational challenges, customers kept paying for the service. “In the beginning, everything was a disaster,” Torrey says. “I wasn’t invoicing people at the right time, and the invoice would just be a text message with a link to PayPal with a line item like ‘soap’ that I would input it by hand every time.”

- Continued demand despite lack of polish: “There also wasn’t anything to indicate that my products were quality. The early refillable containers would come with a rather sketchy label that said SOAP slapped onto an Ikea bottle. Even the delivery process was low-budget — I’d show up on my bike and pull out your toilet paper or hand soap out of my backpack. But people were still using the service.”

“The retention was 100% with those five paid members throughout the pilot,” Torrey says. “The feedback from every customer was ‘I get it. I like that when I go to the store I don’t have to worry about certain things. I don’t even have to think about when something is running low, I just know now that it’s all taken care of,” says Torrey.

RAMPING UP

With the results from his pilot program, Torrey raised a $500,000 pre-seed round from Red & Blue Ventures, Dorm Room Fund and Rough Draft Ventures. The money went into buying inventory and spiffing up the packaging. He also hired his first employee, a former co-worker at his last startup, who moved to Philadelphia to help build the company.

Go-to-market strategy

Rather than approach the business from a purely consumer lens, the initial play for go-to-market strategy was a B2B2C model. That is, Torrey would pitch his delivery service to the building managers as an amenity they could offer, and in turn, the building would promote the service to its residents.

“It was clear to me from the beginning that I wanted to do a B2B2C model. I knew we could be both the vitamin and the painkiller for the building. The vitamin was an amenity. For apartment buildings in big cities, it’s an amenities race to get more residents, and nowadays, the best amenities are around sustainability and convenience,” says Torrey. “But while a Peloton bike in the communal gym might be a good vitamin for apartment residents, our sustainable deliveries were also painkillers for building managers, by reducing all of the packages they have to deal with each day.”

Torrey’s suggestion for early-stage founders is to do as much research into your customer (and, more specifically, their pain points), as well as into your possible distribution channels, as possible. In Torrey’s case, he would observe and chat with building managers to dive deep into their waste management process.

“We knew high-rise buildings were dealing with a crazy number of packages, and delivering those packages was only half of the equation. It was also on the building to dispose of all the waste these packages created. I learned a ton about waste management, like all the fines a building could get for overfilling a dumpster. If the lid is not touching, you get fined, even if it's just an inch off. Buildings were spending thousands of dollars alone on waste management. So the pitch became ‘We are an amenity that will also reduce the number of packages you have and we’ll cut your waste management fees.’”

While Torrey had always hoped the buildings would play a part in marketing Mlkmn to its residents, he didn’t expect them to do it for free.

“The go-to-market became having the buildings advertise to their residents on our behalf,” Torrey says. “They would send an email blast out that the building was offering us as a service and it's now available to all residents, which worked really well. Between that and tabling on-site in different high-rise lobbies we got almost 100 people across three buildings signed up by February 2020.”

A shift in demand

With 100 customers signed up, there was an unanticipated accelerant right around the corner — the COVID-19 pandemic skyrocketing the demand for online deliveries.

By March 2020, Mlkmn was still operating as an in-person home delivery service. Then the lockdowns came. “We took less than 30 days to pause, re-group and figure out what was going on in the world,” Torrey says. “And then we resumed.”

The new game plan was to pivot in-home deliveries to contactless direct-to-door delivery service. Torrey and his early teammate invested in branded reusable bags they could give to all members and prompted them to leave their “empties” (empty bottles of things that needed to be replaced) outside their front door.

“We even started to see customers installing hooks outside their door to hang their refill bags, without any suggestion from us.” He jokes, “I’m not sure how the property manager felt about these new additions, but it was an out-of-the-ordinary gesture from our customers that was an even greater sign of customer love.” he says.

At this point, Torrey was halfway through his first year at business school and running Mlkmn on the side. Mlkmn became an even bigger part of his life when he decided to move into one of the buildings that had partnered with his service to get more visibility into how the business was operating. He also hired his co-founder, Byungwoo Ko (“BK”) shortly after his move.

“BK made the decision to ramp up deliveries from monthly to weekly. He also pushed Mlkmn to expand out of just household toiletries and into anything shelf stable, like your olive oil, your tea, your coffee, your granola, etc.” Torrey says. “We went from those first 20 products to 100 products. We thought about where we could provide the most value. Yes, people still need to go to the grocery store, but can we take all the stuff that isn’t refrigerated? Can we actually give ourselves more of a job to be done that’s bigger than hand soap and laundry detergent?”

Although the team was ramping up its operations and adding in new logistics, they never stopped validating the idea. For each additional step that was added to the original delivery process, Torrey and his team would take the time to test it in person.

“The building I was living in let us use a storage closet as our first fulfillment center. We bought an e-bike and stored it in the closet. We would send out someone on our e-bike to do weekly deliveries as just a test. We wanted to see if operations at this level would work.”

And work it did. After nailing the end-to-end logistics for weekly deliveries, Mlkmn quickly expanded from three to more than 20 buildings across Philadelphia’s city center. The standard Torrey used to mark a successful launch in a building was 20% of residents signing up for the service in the first 30 days of launching in the building. The offering was spreading like wildfire.

With steady growth numbers to show investors, Torrey raised a $4 million seed round (co-led by First Round and Construct Capital) to expand into Washington D.C. “That’s when we saw the hockey stick growth,” Torrey says.

EXPANDING INTO NEW MARKETS

The company had undergone a lot of change in a concentrated amount of time. By early 2022, Mlkmn had rebranded into The Rounds, “because we literally make the rounds in your neighborhood on the same day every week for you and your neighbors,” Torrey says. The team was also gearing up to launch in its second market.

“We took the money from our seed round and launched in D.C.,” Torrey says. “We had to redo our forecasts three times in the first two weeks because we said our goal was to hit 100 members, and we got it in a day. Then we revised to 1000 members, and we hit that on day three.”

Torrey would take the new findings from launching in D.C., and apply those learnings to the original model in Philadelphia.

“Small things like how we did marketing and how we hammered out logistical details, we translated back to Philly and the trajectory of growth there started to accelerate,” Torrey says.

Staying agile

The Rounds remains an adaptive operation that has relied on zapping problems when they come up — rather than sticking to the exact same playbook in each city. When expanding into Miami, one unseen challenge was just how vertically dense the city was. With multiple 60+ story apartment buildings, “Rounders” (the folks delivering refills) were waiting over 20 minutes for an elevator, slowing down their delivery times. They also unearthed new logistical headaches like bike storage (or a lack thereof) when doing deliveries.

Torrey and his team had to tweak their operational process to make it run smoother in this particular city. “We started to refill buildings earlier in the morning to avoid traffic and we were able to be much more efficient,” Torrey says. “We learned that a lot of the building staff in Miami only spoke Spanish, so I got a chance to lean into my own Spanish-speaking skills to help partner with these building managers.”

We intentionally chose very different cities, which was very deliberate to maximize our “learning ROI.” It would force us to prove that the model works everywhere.

In Atlanta, The Rounds’ newest market, the team launched faster and faster in every zip code, but faced the challenge of urban sprawl. The team pivoted by building more fulfillment centers and adding more time for delivery. “What we learned in Atlanta was the power of local products. People love buying local because they can support folks in their community and local vendors like partnering with us because our demand is predictable. So now a third of our assortment in every city is local,” Torrey says.

As The Rounds continues to grow, launch new products and find traction, Torrey leaves founders with his biggest piece of advice for when they are early on in the path to product-market fit: put down the notebook full of ideas, close the spreadsheet, and get started building a “minimum lovable” version of your product.

The easiest thing you can do is talk yourself out of starting. Find a way to test out your idea quickly. Because if you wait too long, chances are you find a way to talk yourself out of it.