This article is by Lenny Rachitsky, a former product lead at Airbnb.

Back when I was a young PM, one of my managers altered the trajectory of my career. It was my second year at Airbnb. I was doing okay, but not great. My new manager, Vlad Loktev, had taken over, just as the project I was overseeing had gotten delayed by weeks. He wasn’t impressed. Although he helped me get it back on track, and we got it out the door, I knew that when performance review season rolled around, it was going to be rough. When the time came, I did indeed get a less-than-stellar rating. Vlad flagged a number of important development areas for me to focus on, including being more communicative about status, and getting more aggressive about prioritizing. While I could have left dejected, I instead ended that performance conversation feeling more clear, motivated, and excited than I had ever been.

Here’s why: Vlad had a simple yet powerful performance review system. The clarity of his feedback, the care in his delivery, and the simple organization of his framework all came together to create a career development experience unlike any I’d ever had before. This set me on a course that catapulted me from a newly-minted IC PM to a manager of a half-dozen PMs, tackling everything from marketplace quality to growth, most recently building out and leading a cross-functional 80-person team driving supply growth at Airbnb.

Over the years, as I transitioned into management, took on a handful of direct reports, and conducted over 50 performance reviews, I adopted and expanded his system into an end-to-end performance management framework that has enabled me to systematically grow junior ICs into star performers, to turn big trouble spots into super-strengths, and build one of the best performing teams at Airbnb.

Figuring that other managers might similarly find this system useful, below I’ll dive into why performance reviews typically suck, how we can fix them, and then walk through this framework in step-by-step detail. Whether you’re a first-time manager looking for guidance on handling your first review, an experienced manager hoping to uplevel yourself from good to kickass, or an early-stage founder trying to put a company performance review system in place, the templates, tactics and real-world examples you’ll find here are yours for the taking.

MANAGERS, AVOID THESE COMMON PERFORMANCE REVIEW MISTAKES

It’s rare that one meeting, once or twice a year, has such a tremendous impact on the morale, performance and trajectory of an employee. Unfortunately, performance reviews are severely underutilized, and often done badly. From the perspective of direct reports, they are more likely to spark dread than hope. On the part of managers, they’re treated more as a chore than an opportunity.

Done well, performance reviews improve performance, align expectations and accelerate your report’s career. Done poorly, they accelerate their departure.

Below are the six most common mistakes managers make with performance reviews:

- 1. Not spending enough time preparing. Performance conversations directly impact your direct reports’ long-term career prospects, morale, and often their identity. If you spend more time filling out expense reports than you do preparing for your performance reviews, you’re doing it wrong. I recommend spending at least three (ideally five) hours per direct report preparing for performance review conversations, every six months.

- 2. Relying too much on peer feedback. Some of the highest performers I’ve worked with ruffle feathers on occasion to deliver the right outcome — which can lead to negative peer feedback come performance review season. (This is especially true in leadership roles.) Here’s why over-indexing on peer feedback is dangerous: If you’re judged solely based on peer feedback, you’ll optimize for what’s expected, not what’s right. As a manager, you need to have your own point of view on how the direct report performed, using the peer feedback as just one input, not the driver of your performance conversation.

- 3. Not providing substantive feedback. Your reports are hungry for feedback. They’re looking at every morsel of information you share with them to figure where they should spend their time. Don’t waste this opportunity.

- 4. Having a one-sided conversation. Too often, managers simply tell direct reports what they think, what to do, and leave too little space for conversation. Leaders want to look strong, and are often insecure about showing any sign of being wrong. An effective performance development process is a mutual commitment to growth and learning, which requires two-way communication and accountability.

- 5. Failing to have a follow-up plan. Most managers have a performance conversation, say their piece, and then expect their direct report to retain and act on everything they heard. When they revisit these topics at the next performance review, they’re often shocked there wasn’t much progress, and fall back on blaming the report for a lack of improvement. It’s not their fault — it’s yours.

- 6. Not doing them at all. There’s a school of thought that says that companies shouldn’t have performance reviews, that feedback should be an ongoing and ever-present. Why wait six months to give feedback, they say, when you can give it regularly and in the moment? The truth is that this rarely works out in practice (i.e. you get no feedback), and more critically, it’s actually a false dichotomy. You should absolutely provide feedback regularly, have consistent weekly 1:1s, and engage in ongoing career conversations. Alongside that ongoing work, however, a regular performance review cadence makes an incredible impact on the trajectory of an employee’s career.

If you can’t find a dozen hours to focus on your report’s career throughout the year, that generally means you have too many reports — or that you shouldn’t be a manager.

FOLLOW THIS THREE-STEP PERFORMANCE REVIEW SYSTEM

As an antidote to the common missteps from above, the system I’ve come to rely on is made up of three equally important parts:

- 1. Prepare

- 2. Deliver

- 3. Follow-up

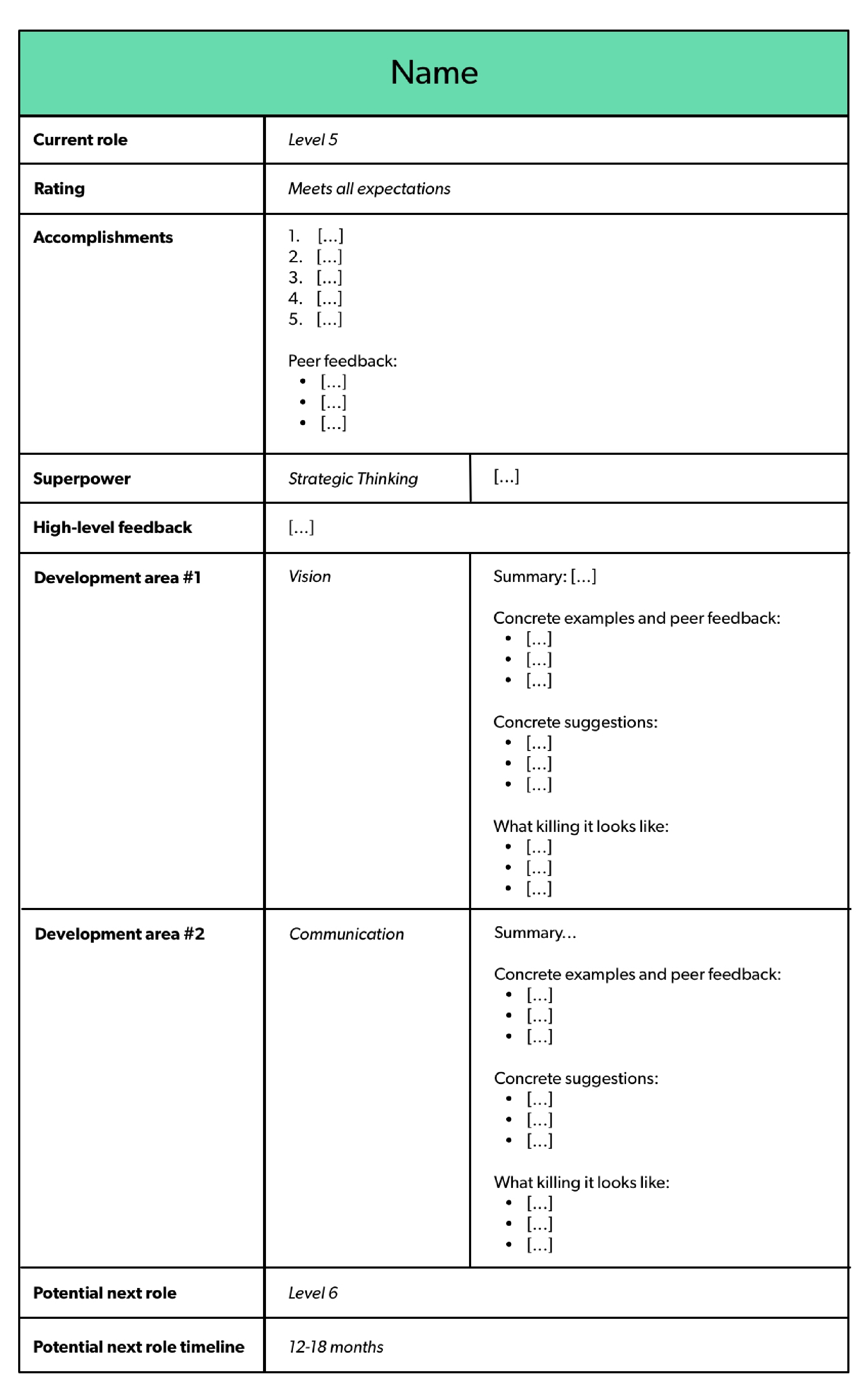

This template forms the foundation of the system, and we’ll walk through each section in detail below. Here’s the Google Doc version of the template for your own easy use. (You can also check out this Confluence template version from our friends at Atlassian.)

STEP 1: PREPARE, PREPARE, PREPARE

This is where the bulk of your time should be spent, as it sets up the steps that follow. Start by gathering data on how your direct report did, both by seeking input from your report’s peers and a self-assessment from the individual directly. You want to get as much signal as possible at this stage, ideally as early on in the process as you can (I typically start at least a month before a scheduled performance chat, since it often takes a while to get everyone’s responses). There are many ways to do this, and most companies have their own system for gathering feedback, but you can always take a lightweight approach over email.

First, work with your direct report to identify five to eight people who’d be able to provide input. Then fire off emails (bcc’ing everyone) asking three simple questions:

Hi Joe,

In an effort to help Jane level up in her career, I’m gathering peer feedback from people she works most closely with. I would really love your input. If you can find 5-10 minutes in the next few days to answer these questions, I would truly appreciate it (and so will Jane):

1. What are 2-3 things Jane should start doing? Why? 2. What are 2-3 things Jane should continue doing? Why? 3. What are 2-3 things Jane should stop doing? Why?

I will keep your answers anonymous, unless you tell me otherwise. Please be honest and candid, as that’s what’ll help me give Jane the best support in her career. And, if there’s anything else you’d like to share, good or bad, I’d love to hear it.

Thank you!

In parallel, ask your report to do self-review, with an email such as:

Hi Jane,

Ahead of our upcoming performance conversation, I would love to get your perspective on how things went. Could you please answer these three questions, along with anything else you’d like to share, and get back to me by X/X?

1. What were your top five accomplishments in this cycle? 2. What 2-3 areas do you want to focus on developmenting over the next cycle? 3. What are your goals for your career over the next two years?

Thank you!

While you’re waiting for the feedback, I strongly recommend you start crystalizing your opinion on how your report performed. What did they do well? What is keeping them back? What are the one or two most critical development areas for them to focus on over the next cycle? This is a key step to reducing bias and avoiding being completely swayed by what peers say.

As you begin to gather your thinking, and as peer feedback begins to roll in, start to flesh out the template referenced above, which you’ll eventually share with your report. Let’s walk through each section:

Accomplishments: Detail the person’s accomplishments over the course of the period. Collect these from the report’s self-review, peer feedback, and your own notes that you’ve been keeping throughout the year. Each item here should be significant and meaty. For example, write “Hit team’s goals” and “Shipped project X on time and under budget," not “Held a great meeting” or “Went to three conferences." In this same section, I also like to include a sampling of the best positive peer feedback I’ve collected, ideally three to five of the best quotes about the person (anonymized of course).

Superpower: Most performance reviews over-index on development areas. The reality is that an individual will have just as much impact (if not more) on an organization if they flex what they are really good at, instead of just trying to improve on the areas they’re struggling with. Here, you have a chance to highlight that. Describe their biggest superpower, and how they can flex it further. A few examples of superpowers that I’ve highlighted in the past include a special knack for storytelling, execution, or galvanizing a team. There’s a lot of research that shows focusing on strengths is much more effective than obsessing over weaknesses. Note that it’s important to watch for bias here, since many of us unconsciously describe the same behavior by men as a strength and as a weakness by a woman. (You can read more on this topic here, here, and here).

High level feedback: Next, I take a step back and summarize the report’s performance in a short narrative, about four to six sentences. I try to make a simple story arc, starting by describing how far they’ve come, then a sentence or two about how they did this cycle, and ending on a high-level overview of what they need to focus on next.

Development areas:

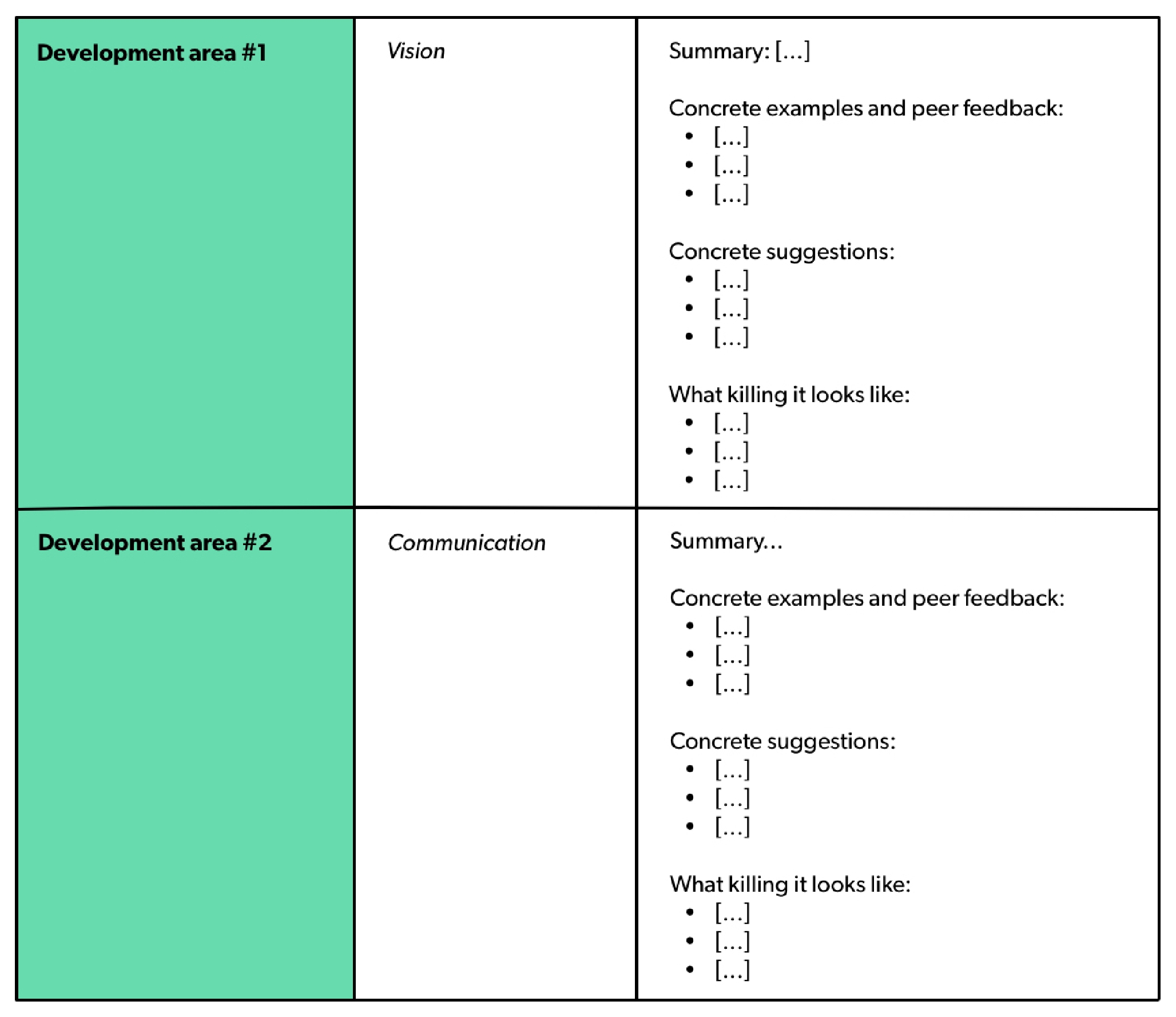

Identify one to two development areas to focus on for the next cycle, and put them in the middle column (see the screenshot below). This part is core to the performance review, so selecting these with care is absolutely critical. A few specific suggestions for how to nail these down:

- What is most holding the person back from the next level? If your company has a leveling system, leverage it to explain your thinking.

- Do any clear themes emerge from the peer feedback or self-review?

- If your company does calibration, is there a key issue you’re hearing from other managers? Even if it’s not something you agree with, it’s something you’ll need to address.

- Make sure you still identify important development areas for even the highest of performers. No matter how amazing someone is, there’s almost always something they can focus on to get to the next level.

A few examples of potential development areas include reliable execution, increasing code quality, and more succinct verbal communication. Don’t worry so much about making the descriptions super comprehensive here, as the details will be filled into the next column. A common mistake here is including too many development areas (more than two makes it very hard to make meaningful progress on any), or not making the development opportunities concrete enough (where your direct reports are left guessing at what you really mean).

Filling in the details within each development area:

This right-hand column is where most of the content — and eventually most of the in-person conversation — goes. The goal here is to make it very clear what the development opportunity is, why it’s so important, and how to concretely improve at it. I often find myself refining this section up until the last minute.

For each development area, include:

- A short summary describing the development opportunity. Here’s an example: “Your team has lacked a clear strategy for the past six months. Without a strategy, it’s unclear to your team how all of the work they’re doing fits together, and it makes it hard for anyone outside of your team to understand why you’re prioritizing the things you’re prioritizing.”

- Concrete examples of this not going well. Include quotes from peer feedback that support those points, and any examples you can recall where this caused a problem, led to a complaint, or came up in a meeting. Build a habit to note these instances throughout the year.

- Concrete suggestions for improving. This is where you share your wisdom and experience in leveling up at this skill. What do you suggest they concretely do to significantly improve at this skill? Be direct, ambitious and constructive. Eventually this will inform action items that you’ll work with your report on. I often include articles and books to read, people to talk to, and things to experiment with. As much as possible, leverage the superpower noted above, along with any other strengths you recognize, to level up in this area. For example, if their development area is around verbal communication, a suggestion could be “Take a public speaking workshop.” If their development area is around improving execution,” a suggestion could be “Have a weekly check-in with your team where everyone reviews timelines, blockers, and priorities.” If their development area is around hitting deadlines, a suggestion could be “For the next five projects, spend extra time estimating the work.”

- What “killing it” would look like. Don’t underestimate your reports by letting them settle for good enough. Work backwards from what the perfect next six to 12 months would look like, and describe that in this section. Don’t expect anyone to achieve this, but give people space — and inspiration — to stretch.

Ambitious people want to know not just how to get better, but how to blow it out of the water. Paint that picture for your direct reports — what would “killing it” look like by the next performance review?

Timeline to next level:

Finally, leave your report with a sense of how far they are from the next “level.” Even if you don’t have official levels at your company, include a meaningful milestone for your report to be excited about reaching (such as becoming a manager, expanding scope, or a title change). There are three common archetypes of situations here:

- So close: These people are right on the edge but didn’t quite make it. I use an estimate of six to 12 months (assuming you meet every six months to evaluate performance), and when appropriate verbally share that it’s likely much closer to six months.

- Just got promoted: These people are not too worried about reaching the next level, so be super realistic about how long it’ll likely take. I normally say 12 to 18 months.

- Doing fine: This is the most common case, and it’s generally going to be six to 12 months.

STEP 2: DELIVER

There’s a lot more to performance reviews than simply sharing the rating, development areas, and change in comp – how it’s delivered, and the conversation that it sparks, is a vital part of making change happen. I’ve had performance reviews where I received a low rating, but I left energized and motivated. I’ve also had reviews where I got an amazing rating but left unsure about my future. That’s because people want context, clarity, and most of all, next steps.

How you message the feedback — and how your direct report feels afterwards — is often more important than the actual content itself.

Here are a few tips for prepping yourself to deliver the performance review:

- Schedule it: I book 45 minutes on my direct report’s calendar for the performance conversation. I’ve tried 30 minute and 60 minutes, but there’s something about 45 that seems to work particularly well. Put it on the calendar as soon as you can, partly to let your report know it’s coming, and partly to create a forcing function for yourself. I generally book an extra 30 minutes for myself before the meeting to prep (whether that’s printing out copies, reviewing the key points, or rehearsing the flow).

- Prep your narrative: Either in your notes or in your head, script out how you’re going to walk through the review. I have a few suggestions below for how to kick things off and the sequence to follow, but figure out what works best for you. Don’t show up without at least thinking through your intro and the sequence of key points — “winging it” is not a good strategy here.

- Send ahead: On the day of the chat, I generally email the doc a few hours prior to the meeting. I find this gives the person time to process the content, instead of reacting real-time in the moment. It also usually leads to a richer discussion during the meeting. I’ll caveat that this isn’t always a great idea, particularly if the report will be very surprised or disappointed with the review, so do what feels right for your situation.

- Bring paper copies: This is a small thing, but I’ve found it to be very impactful. I print out two copies of this doc, one for me and one for my report. I bring them to the meeting, along with a highlighter, which I use to highlight important points that come out of our discussion. The physicality of the paper adds an important dimension, keeping the conversation focused and grounded in the facts.

With that prep work taken care of, here’s how I generally sequence the conversation in the room:

Intro: I start each conversation by lightening the mood and checking in with how the person is doing. Everyone is going to be on edge — find a way to make it feel a little less intense. Then share some context about the chat:

- Make it clear this is very much a conversation, and that it’s okay to fire off questions and thoughts as you’re going through it together.

- Remind them how seriously you take these opportunities to talk about career development, highlighting how much time and effort you’ve put into it.

- Share a brief agenda of the meeting, touching on how you’ll walk through the review, share any compensation updates, and leave plenty of time for Q&A.

Share the rating: Some sort of rating scale is generally helpful for reports to get a concrete sense of where they are, so if you don’t have this yet at your org consider introducing it by the next cycle. I try to share the person’s rating as early as possible in the conversation. This is the most immediate thing on people’s mind and I find people don’t fully pay attention until they know how they “officially” did. If it’s not an amazing rating, address that, but don’t dwell on it for too long. Instead move forward, so that you can spend time talking through the opportunities to level up. As much as possible, make sure the performance rating doesn’t come as a total surprise. Your report should generally know how they’re doing through regular chats throughout the year. If the rating is really problematic, this part takes special care and attention, and often involves working closely with HR.

Dive in: Walk through the doc. If you sent it ahead of time, and the person read it, then just hit the big points. Pause along the way and ask if everything makes sense or if they disagree with anything. Make sure you’re watching the time, and spend at least two-thirds of the meeting on the details within the development areas. When you get to tough stuff, I’d encourage you to be open and vulnerable. When possible, share personal experiences of when you yourself worked on these very same development areas, what struggles you had, and how you overcame them. The more this feels like you are on their side and there to help them succeed (instead of judging or berating them), the more likely they’ll accept the feedback.

A few common reactions to watch out for during the conversation:

- Gets defensive or upset: If you notice this, hear them out and truly listen to their point. There’s always a chance you missed or misinterpreted something. Even if you didn’t, you want to give them a chance to share their perspective. If it starts going in circles though, try to zoom out and move on to the next point. Don’t get stuck on one issue. If it’s still a problem at the end of the conversation, and you haven’t been swayed, stand behind your opinion. Make it clear that it’s okay if you disagree. Talk about next steps, and agree to see how things go over the next six to 12 months.

- Goes quiet: This is the most typical reaction. The review is a lot of information to take in at once, so most people are in listening and processing mode, which is fine. But, if it feels too quiet, simply point it out, e.g. “I’m noticing you’re really quiet, I just want to make sure this is all making sense? Any thoughts or questions before we keep going?”

- Looks dejected or overwhelmed: This sometimes happens when you have way too much information to share, or the review is negative. In these cases, slow down. Keep checking in. I sometimes stop the review conversation and pivot to a heart-to-heart. Find out what’s going on with the person. Sometimes they take it much harder than they need to. Sometimes they have other stuff going on in their life that’s showing up here. Come back to the human-to-human connection and don’t worry about getting through every nuance and detail of the review.

Share compensation updates (if there are any): Finally, share any compensation updates. This normally ends things on a happy note. Keep it simple, share the facts, and congratulate the person on the achievement. It’s easy for employees to take a raise for granted and not treat it as a big deal, so use it as an opportunity to remind them how much you value their great work.

Leave time for discussion: Then, open it up to any remaining questions and thoughts. Is there anything your report disagrees with? Is there anything they want to dive into further? Is there any more clarity you can give around expectations for the next cycle? Try to give this at least five minutes. That being said, I try not to linger here too long if there isn’t anything pressing, especially if things seem to be in a good place. Often folks need time to process and think about everything they’ve heard, and you can follow up on it in future 1:1s.

Follow-up action plan: Finally, turn this discussion into an action plan (you’ll find guidance on how to do this below). This will allow you to channel all of the ideas, motivation, and momentum into an ongoing structured discussion that holds both of you accountable to making change.

Outro: Find a way to wrap it up end on a positive note. Remind them how valuable they are to the company (if they are), how much you enjoy working with them (if you do), and how much potential they have at your company (if they do). And last but not least, let them know that if anything comes up until you chat next, to not hesitate to ping you.

STEP 3: FOLLOW-UP

As George Bernard Shaw famously said, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

We want to believe our carefully-chosen words of wisdom are interpreted correctly and seared into the minds of our reports. It’s safer to assume they aren’t.

Early in my management career, I had a report that was underperforming. I put hours into preparing for our performance chat. I identified development areas, included numerous examples, and shared tons of suggestions. I talked through it in our hour-long meeting. I felt like I made a real impact. A month later, I revisited our discussion and it felt as though it never happened. My direct report had vague memories of a few points I had mentioned, and a clear desire to improve, but 95% of the message was lost.

In that moment I learned two lessons. One, it’s my fault as a manager if my report doesn't remember what development areas to be focusing on. Two, I was treating the performance conversation as the end, when it’s really only the beginning of the performance development process.

The solution to both of these problems is simple — set aside dedicated time to check in, and hold each other accountable. Here’s how you make this happen:

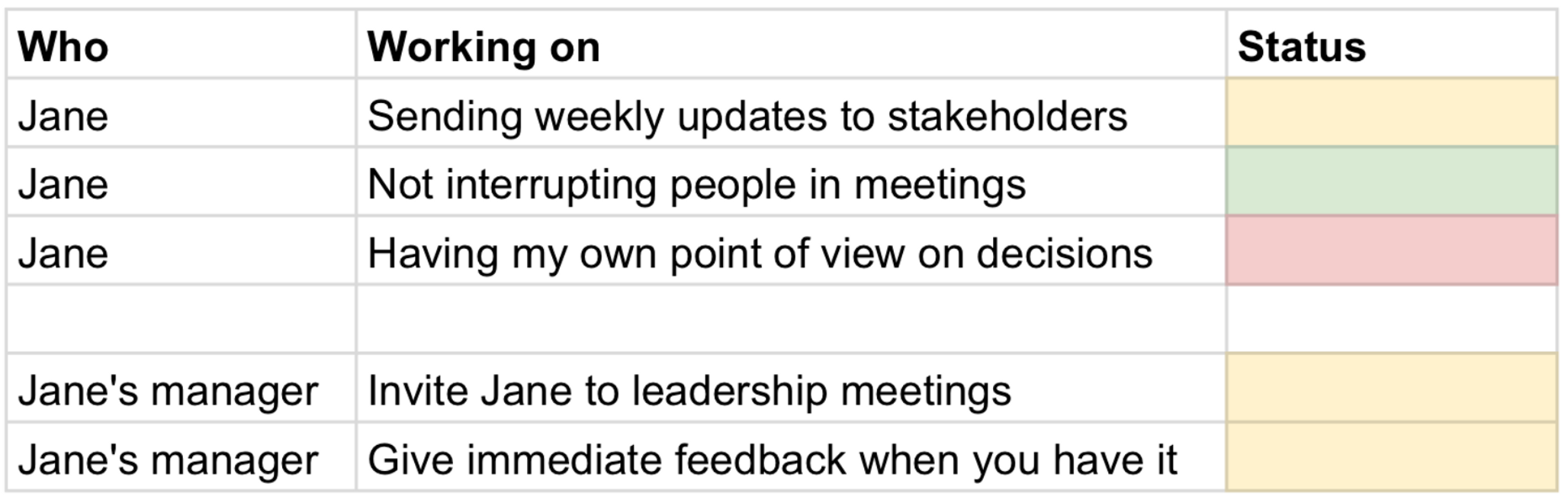

Create a two-sided action plan: Building off the performance review document, at the end of your conversation (see above), ask your report to list five to seven concrete actions they want to work on over the next six months and add them into a super simple spreadsheet. Give them a week to do this, while it’s still fresh in their minds. Here’s a template you can use, and a few examples:

Alongside this list, make sure they also include what they need from you in order to be successful. It’s important that your report owns this process and chooses the items (with input from you) because they’ll need to be motivated to actually work on these things. The list should be made up of concrete suggestions you noted in their performance review, things your report personally wants to work on, and things that your report needs from you in order to be successful. Put a status color next to each item, and update it every month.

Schedule a one-hour monthly check-in: Put this meeting on the calendar immediately. I call it “Monthly Career Coaching,” to distinguish it from our weekly 1:1s. The focus of these meetings is to step back from the day-to-day and focus on career and performance development. No talk of how a project is going, upcoming deadlines, or blockers (that’s for the 1:1s). Remind your report ahead of each meeting to update their spreadsheet with a status and any new discussion items they’d like to make time for.

During the Career Coaching hour: In this meeting, you have three goals:

- 1. Check in to see how your report is making progress on their development areas.

- 2. Make sure they have everything they need to in order to move the ball forward.

- 3. Ensure the list of action items they’re focusing on is still the right list.

The meeting should be mostly you listening, asking questions, and (when really necessary) offering suggestions. Your report should lead the meeting — go through each item in the action plan, share a brief update, and align on the status color. I find most of the time my report is right-on with their assessment. If you disagree, discuss it. Throughout the discussion, instead of telling your reports exactly what to do, help them figure it out for themselves. When asked for the answer or advice, turn it around and ask “What do you think the right approach is?” or “Before I answer, what do you think?” (This book from David Rock and Julie Zhuo’s writing have taught me a lot about how to be a better manager by asking good questions.)

Between chats: Keep track of instances where your report did well, didn’t do well, or generally did something noteworthy. Share these things with your report in real-time as much as you can, or in weekly 1:1s, but also save them in a running file. For example, “July 10th - Ran an excellent meeting with senior execs,” or “Sept 3 - Put together a very strong strategy for Q3,” or even feedback from others (“Jan 4th - Spike shared with me how impressed he is with Jane’s ability to run a meeting.”) I keep a separate Google Doc for each of my reports for this purpose. In addition to Google Docs, there are neat feedback and performance management tools like Matter, Culture Amp, and TINYpulse that can help you keep tabs on performance throughout the year.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER

As a manager, the best feeling in the world is watching your direct reports grow. I’ll never forget a junior PM that came to our team with considerable gap in their collaboration skills. After identifying that development area, working together through the process above, and then revisiting it six months later I was thrilled to see nearly every instance of peer feedback call out that this was no longer an issue — and in fact, this report’s development area had turned into a strength. All it took was infusing performance reviews with more structure, attention, and intention.

Here’s a recap of the process:

1. Prepare

- Gather direct feedback — from your report, and from their coworkers

- Capture their accomplishments

- Describe their “superpower”

- Write a short high-level summary of their performance

- Identify 1-2 development areas, with examples, concrete suggestions, and what “killing it” would look like

- Share a timeline for their next career milestone

2. Deliver

- Schedule it

- Prep the narrative, bring paper copies

- Break the ice

- Share their rating

- Walk through the details, spending most time on the development areas

- Share compensation

- Create a follow-up action plan

- Leave time for discussion

3. Follow-up

- Schedule a one-hour monthly coaching chat

- Review the action items together, adjust as things progress

- Capture and share examples of what’s going well and isn’t throughout the year

Even if your company already has an established feedback or performance review process, you can easily map this system onto that process. I find that there's a lot of room for managers to have a more bespoke, personal approach that persists through cycles and organizational changes. Don't just take the forms and talking points from on high and have a perfunctory conversation. Put in the legwork. You’ll notice the impact immediately, and be on your way to becoming a better manager.

Huge shout out to Vlad Loktev for too many things to name, including his contributions to this post, and to Helen Sims, Yelena Rachitsky, Eric Ruth, and Brett Hellman for reviewing early drafts.

Photography by Bonnie Rae Mills.