There was a time when Wes Kao thought that to be a leader, she would have to change. Leaders, she believed, had to look and act a certain way — serious. Buttoned-up. Formal.

When she co-founded Maven, an online cohort-based course platform, Kao was thrust into an executive role, and she quickly began unlearning her preconceptions. The company culture that emerged organically at the startup helped her reflect more deeply on how a leader should speak or behave. “We weren’t serious or corporate for the sake of it,” she says. “It allowed us to be ourselves, and care about the quality of the ideas that we were sharing.” This suited Kao. “I think I’m a pretty professional person,” she says, “but I don’t think I’m the most formal person.”

Back then, Kao was still figuring out her leadership style. She would often notice, in meetings or at events, that one of her co-founders would make a comment that Kao felt she could never get away with.

“He would say certain things and people would love it. If I said something similar, I just knew it wouldn’t land the same way, and vice-versa.”

This observation planted a seed that would bloom into Kao’s own unique communication framework: personality-message fit. If you shape your message to suit the tone, style and quirks of the way you naturally communicate, Kao argues, rather than adopting an approach that feels forced, connection with your audience will come effortlessly. This might be in a hard conversation with your co-founder, on a call with a prickly customer, or when pitching a room of potential investors.

“I don't think that we, as founders or leaders, can change 180-degrees, even if we want to,” Kao says. “We've all seen somebody pretending to be Steve Jobs, or trying to be Mark Benioff, and it’s not landing. It's better to know, ‘this is how I am, this is the constraint, and these are the levers I have to pull for people to better understand me.’”

It’s about more than simply being authentic. “That word gets thrown around a lot,” Kao says. “I don’t know if I believe there’s one true way to be ‘authentic.’ We can be different versions of ourselves in different settings, in different contexts, with different people.” Charisma, too, is a concept so broad and abstract it’s hard to translate into actionable steps. What Kao is talking about is more strategic. “You see founders of all types, styles, and idiosyncrasies being successful,” she says. “It’s more about what makes you you, instead of trying to copy someone else and having those tactics fall flat. There's a lot of things you can do to evolve, grow and get better in the way that you communicate.”

In this conversation, the executive coach and entrepreneur, who in addition to Maven co-founded the altMBA with bestselling author and marketing trailblazer Seth Godin, shares how founders can develop personality-message fit, first by finding their own voice, and then by learning how to make it land with others.

Part 1: Personality

Self-reflection is the “personality” side of finding personality-message fit. Before thinking about an audience, you need to understand yourself: how you show up, what feels authentic, and where you naturally shine.

Do an internal audit

When it comes to personality, disposition, and temperament, Kao says “it’s important to understand what your baseline is.” Ask yourself how it feels most natural to you to present in different settings, from pitching in a boardroom to mingling at an event, or speaking to a large group versus in conversation with a few people. Does it feel natural to joke, or be more reserved? To lead with data, or begin with a story? To hold attention with practiced pauses, or exuberant energy? “How do you react to things?” Kao asks. “Where does your head naturally go? Then, if you want to make adjustments, you can — but you have to know your baseline.”

Armed with that information, you can adjust the delivery of your message accordingly. Kao gives the example of an executive coaching client who is relatively inexpressive; she could barely tell when he was happy or upset. Kao’s advice to her client was not to learn to emote more, or force himself to make more animated facial expressions, which would only feel contrived. “If you want people to know how you feel,” she says, “you need to amp up other levers. Instead of trying to be high-emoting, or relying on your facial expressions or tone of voice to do the heavy lifting, you can turn up the enthusiasm with the choice of the words you use.”

By deliberately choosing language that signals energy (phrases like “I’m very excited” or “this has me feeling fired up”) Kao’s client was able to show conviction without faking it. Kao says it’s about finding subtle ways to make your intent clear, even when your delivery is naturally understated.

The second part of conducting an internal audit is to assess which kinds of professional communication feel natural and effortless to you, and which feel more like pushing a boulder uphill.

“It’s helpful to take stock of the parts of your role that light you up, and the parts you have to summon internal fortitude to get through,” Kao says. For example, do you shine when chatting with investors or customers at a casual event, but clam up speaking in front of the entire company at a town hall, or vice-versa?

Pay attention to what gives you energy versus what feels like it’s depleting energy, or something that you dread, and to your excitement level — that’s the clue.

Conducting an audit will also help you identify if there has been a drift over time, where your day-to-day responsibilities have become increasingly centered around the kind of tasks at which you don’t excel.

“Your role might have been aligned with your strengths when you started, but it might now be only a small fraction of what you like doing. It's easy to get pulled in a bunch of different directions. You might look up one day and realize you're working on a bunch of stuff you don't enjoy and you're not very good at.”

The audit doesn’t have to be overly structured. Kao recommends occasional reflection, whether through journaling or quick self-checks after big projects, to course-correct before burnout sets in. “I'm a big proponent of stream-of-consciousness writing. I do a lot of reflection that way. The other aspect is noticing strong feelings either way; I see strong feelings as clues our bodies are trying to tell us.”

Practice the 30-second prep habit

In Kao’s experience, most communication issues can usually be traced back to the same root: a lack of preparation. “It’s the biggest bottleneck to clear communication. We often jump from one meeting into the next, and answer Slack messages in between. I think people just don't put enough thought into their communication.”

And while you would undoubtedly prepare for a high-stakes meeting, you might not prepare for a quick Slack huddle or a walk-and-talk. But Kao says smaller moments of communication also require preparation to be fruitful. “When you’re speaking in real time, your brain is doing a bunch of different processes at once: processing, thinking, connecting it to past context, formulating a response, and then saying it out loud, all in milliseconds. If you aren’t clear about what you’re trying to say, it’s going to be confusing.”

Drawing on the data you have from your internal audit, Kao recommends spending as little as 30 seconds asking yourself a few clarifying questions before a conversation. “A couple of moments can make a big difference. It allows you to speak up on a call, or in a meeting, in a way that gets your main point across much better.”

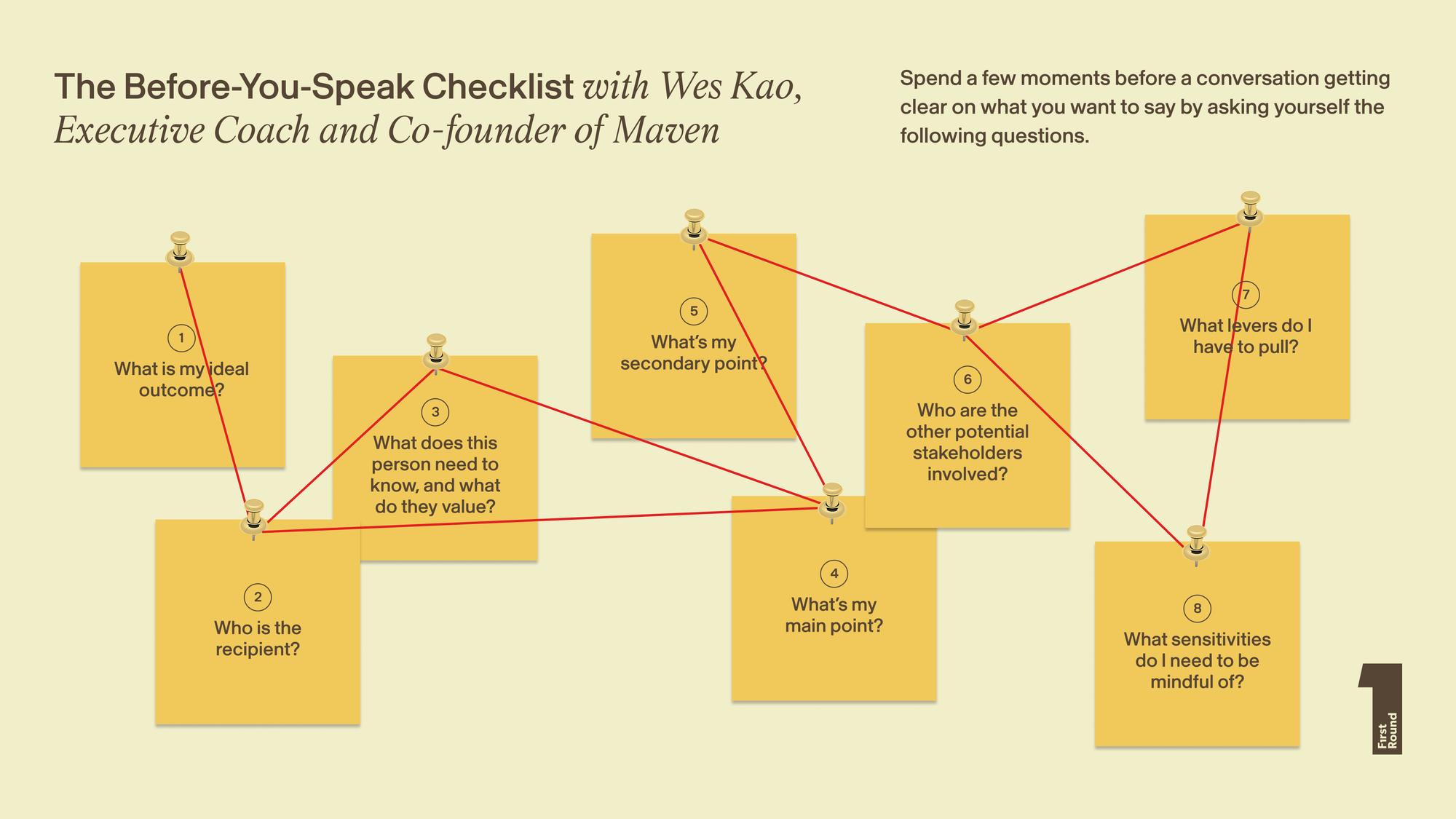

Kao suggests jotting down notes, or simply reflecting. “Instead of sharing whatever comes to mind, start with your ideal outcome, and work back from there.” Questions to ask:

- What is my ideal outcome?

- Who is the recipient?

- What does this person need to know, and what do they value?

- What’s my main point?

- What’s my secondary point?

- Who are other potential stakeholders involved?

- What are the levers that I have I could potentially pull?

- What are any sensitivities that I need to be mindful of in this situation?

Working backward from your desired outcome is key. Kao shares an example of a coaching client, the head of finance at a Series A company, who was going about persuading the founder/CEO the wrong way.

“He wanted to convince them to adopt a more standard way of measuring CAC. My client said they wanted to be heard. But in reality, the ideal outcome was that the CEO would agree to calculate CAC in a certain way.” Kao helped the head of finance to work backward from there to determine how they should communicate the ask.

“What is most likely to appeal to this person, based on what you know about their worldview? You’re not going to get very far in my experience, trying to force them into entering your world. It's much better,” Kao argues, “to frame your recommendation under an existing umbrella of what they already care about and how they think the business should be run.”

Part 2: Message

Finding your personality-message fit requires more than self-reflection. You’ll also need to conduct research in the field — to try different approaches, adapt them to your audience, and see what actually lands. “You can’t pontificate in your own mind endlessly and then come to a breakthrough. You can’t know what’s resonating until you go out and try. You have to get reps,” says Kao.

Learn to read the room

Some people seem born with the ability to sense a shift in energy, or spot confusion before anyone speaks up. “They're naturally better at this,” Kao says. “Better at noticing the reactions of others and asking themselves, ‘Was that the reaction I was hoping for? If I approach it this way, am I going to get the reaction I'm looking for more?’ But it’s a skill you can get better at.” Kao advises approaching reading the room as a muscle you can build, not a talent that either you have or you don’t.

“I take an experimental, iterative approach, and it's very much first principles based. I’ll try a bunch of different things along the way to see, does that feel natural for me or does that feel off?”

The people who seem naturally good at reading the room, Kao says, are just the ones who’ve practiced noticing. “From far away it can look like magic, but if you come closer and dissect what’s happening, it can be broken down into component parts.”

Kao advises starting by sharpening your observation skills in professional settings, from presenting a deck to networking at an industry event. “Notice the reactions of others. Ask yourself, did I get the reaction I was hoping for? If not, what could I do differently next time?”

She encourages making small tweaks in low-stakes settings — for example, your tone, framing, or order of ideas — and to watch what changes. Think of it as A/B testing. “There’s no silver bullet,” she says. “Try things, and be honest about the reaction you’re getting. That’s how you get closer to the reaction you want.”

It’s important to take note of more than what’s said out loud. Kao distinguishes between explicit feedback (what people tell you) and implicit feedback (what they show you). “Most people over-index on explicit feedback,” she says. “If you take a step back and notice more, you’d probably see that this thing was bothering that person long before they spoke up about it.”

Make a habit of scanning the expressions and body language of your audience mid-meeting, and adjust your strategy in real-time. “If you can tell that it’s not really working, that’s a sign to switch things up.”

Go deeper on feedback decoding

If you receive feedback on your communication style in a more formal capacity, such as from your co-founder or an investor, Kao warns against rushing to make changes without first probing for specifics, especially if the feedback is vague. “Three months later when you check in with that person, you might find that what you thought they meant was not what they meant at all.”

Don’t accept vague feedback at face value. Ask follow-up questions until you can define what the other person means. Kao gives an example of the common piece of feedback founders get to be more strategic. “You might ask, ‘when I did this thing, would you say that that was strategic, or did it not feel as strategic? What are some examples from my peers that you feel are strategic?’”

Kao warns that not everyone is skilled at providing specific feedback, so it might take a few attempts to glean the information you need. “They might not be able to share more specifics if you just ask them point blank. You may need to ask indirectly. Draw that information out of them.”

Once you’ve gathered examples, read between the lines. “You might notice a pattern; maybe a peer always starts with context, or they’re great at stack ranking what matters most,” she says.

This approach does two things at once: it forces specificity from your manager, and it gives you a clear map for how to adjust. “It’s much easier for most leaders to react to something in front of them than to define what they mean from scratch.”

The result of feedback on your communication style should be that you have clear, actionable steps to take to make changes. “It’s your job to unpack it, clarify it, and get to that next level of specificity so you can fix the right things,” Kao says.

“You might normally start talking in a chronological way about what happened starting from the past three months up until now,” Kao says as an example. “That is going to be confusing for someone who is hearing about this for the first time.” How you could shift your approach based on feedback is to frame the topic up front, and tell your audience directly what you need from them.

“You could say, ‘we’re here to talk about the new feature we're launching. What I'm looking for is your feedback about whether this is clear, and if so, we're going to launch next week.’ Saying something like that versus jumping straight into the deep end means the audience will understand more clearly what you’re trying to say.”

Own your spike

Everyone has strengths and blind spots. For founders, those spikes are magnified, since they tend to show up in the culture and direction of the company itself. Kao says spiky traits are valuable, not something to be sanded down to be inoffensive.

“Most founders have a pretty strong point of view about the way things should be,” she says. “You want founders who have a strong point of view, who are obsessed about whatever they're obsessed about. I don’t mean stirring the pot with controversial statements just for the sake of it. I mean having a unique stance based on your lived experience that you can back up with evidence, stories, and logic.”

Kao encourages founders to share their spiky opinions with pride, with the intention of teaching people something new. “If you’re just saying stuff people already know, that’s not very useful,” she says. “The content that resonates is the kind that helps people think differently, that challenges a viewpoint in a productive way and gives clarity to a problem they’re dealing with.”

It’s a principle Kao applies to her own personality-message fit. “Almost all of my content starts with considering: what’s my spiky point of view here?” she says. “The stuff that performs best is usually rooted in something that triggered a reaction in me — either I strongly agree, or I strongly disagree.”

She encourages founders to use that same instinct as a guide.

If something triggers you, if you find yourself thinking ‘this is annoying’ or ‘this is fascinating,’ that’s where your best material lives. That’s where you have conviction.

Spiky opinions don’t just get attention; they build credibility. They tell people what you stand for and help attract those for whom your message is more likely to strongly resonate. “It’s not about being loud for the sake of it,” Kao says. “It’s about being specific, grounded, and true to what you actually believe.”

But pay attention if something about the way you communicate, whether it’s style or content, seems to be consistently bothering people. “It’s useful to be self-aware of the ways that you might be impacting the people that you work with,” Kao says. “If you’re consistently getting feedback that a part of your behavior isn’t productive, it’s up to you to decide if you want to continue that and live with the consequences, or change it. By the time anyone's speaking up, it’s probably been bothering them longer than you knew.”