Here on The Review, we’ve dedicated thousands of hours to detailing every aspect of company-building, which includes exits. We’ve covered prepping to take your company public or the decision to sell, but haven’t spent as much time on the process of merging with another company as a founder. They’re uniquely difficult to execute well. A majority of the time they don’t work because bringing two companies together — balance sheets, cultures, products and people — is far more difficult in practice than one company subsuming another.

Bob Moore, co-founder and CEO of ecosystem revenue platform company Crossbeam, knew the odds of a successful merger were against him. But he also knew the high rate at which startups fail in general. So when he saw the opportunity to materially change the trajectory of his company by merging with its fast-growing competitor, Reveal, it was a decision he didn’t take lightly.

From the outside, between vague headlines and PR talking points, M&A is inscrutable. And if you’ve never run a deal process yourself, you might be surprised at the sheer number of details to make it work. In this essay, Moore goes into extreme detail about every aspect of the odds-beating merger — its structure, the values they created, messaging, how they migrated thousands of customers and much more. We thought the best person to tell that story was Moore himself.

With that, the floor is his.

Disclaimer: The information in this document is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as legal advice. Both parties were represented by experienced legal teams who guided the deal through complex regulatory, tax and cross-border considerations. Any legal decisions should be made in consultation with counsel.

Everyone told me this would be a bad idea.

When I was considering merging my company, Crossbeam, with our fast-growing competitor, Reveal, I understood a harrowing statistic: mergers fail ~75% of the time. Most of my advisors — and most of my board — disliked the idea. Some feared distraction, some were skeptical we could align on terms, and some would have preferred that we just tough it out on our own.

But two reasons led me to quickly gain conviction that it was the right move for us: The dynamics of our market and the alignment of our founders.

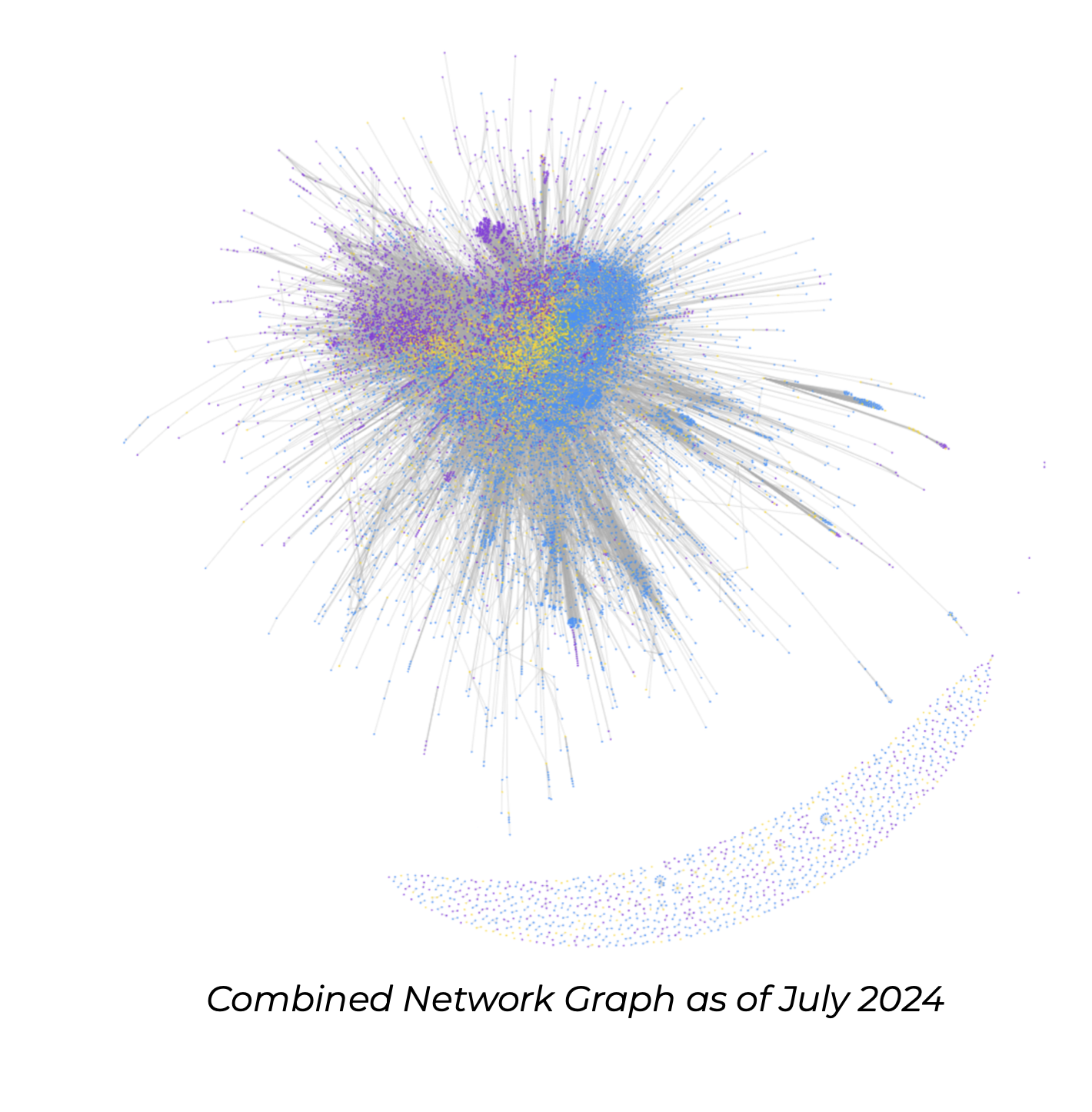

Companies like HubSpot, Stripe, and Anthropic use Crossbeam to identify and share overlapping accounts with their partners. They use this “second-party data” asset to enrich their own data, reveal insights about how to win deals and find signals that indicate who else they should be selling to. Some people liken it to “LinkedIn for data.”

At the time of the Reveal deal, we were approaching $10M ARR with some incredible logos in our roster and about 800 paying customers.

Users and ARR were up-and-to-the-right, but if you dug a bit deeper, you’d find a different story.

We were spending way too much cash to generate each incremental dollar of revenue (our burn multiple was 5.9x) and revenue came too slowly — even with self-serve revenue picking up, sales reps endured an average 59-day sales cycle for below-market ACVs. We were trapped by the physics of our own business, and with interest rates rising in the post-ZIRP era, this wasn’t a tenable situation.

We hypothesized a few reasons for this, which Crossbeam’s frontline teams felt acutely:

- We were in the midst of a slow and expensive “category creation” journey, requiring our buyers to carve out new budgets for a new product class that had to be sold to multiple stakeholders internally in order to purchase.

- The existence of Reveal in the market was causing our network to split down the middle, leaving most customers straddled between two platforms, not able to get the full value out of either of them. (Imagine if there were two LinkedIns! Not only would you have a painful time finding a contact, which of those companies’ Sales Navigator product would you buy? Probably neither.)

- The combination of the two points above made it impossible to mature and scale a pricing model. We just couldn’t repeatedly connect the value we created to the prices we charged.

If we were right about network effects and the power of our platform, then we should’ve been growing much faster.

But in reality, our journey to $10M ARR had felt like chewing glass, and we still saw a buffet of it ahead of us.

These challenges ultimately limited our ability to deliver value to customers. Crossbeam and Reveal operated independently, and our overlapping efforts created confusion in the market. Instead of combining strengths to deliver a more complete solution, we were leaving customers without the full, unified experience they deserved.

In this essay, I’ll explain how we architected a once-in-a-lifetime merger to completely change the trajectory of both businesses. Here, I’m holding nothing back — from the structure of the deal, to the process for integrating the companies, to how we merged our customers, our products and more.

Genesis of the deal (and why it almost died before it even started)

It took 18 months from conception to completion for this deal to happen. For most of that time, it looked completely dead.

I met Reveal’s CEO, Simon Bouchez, at an industry conference in 2022. This wasn’t a normal meeting of competitors: we laughed.

Crossbeam had a silly mascot running around handing people drinks and Simon had just gotten off stage where he was introducing a made-up word (he coined the term “nearbound” as a category-creating term akin to our later “ecosystem-led growth” tagline). The absurdity of our situation wasn’t lost on either of us and we were quick to empathize.

As it turned out, we were both repeat founders fascinated with solving the same problem. We had kids almost the same age. We were confused about why we chose to attend a conference in Miami in August. Most importantly, we admitted to each other a hard truth: Because our companies rely on a network effect, our customers would all be a lot happier if there was only one of us out there.

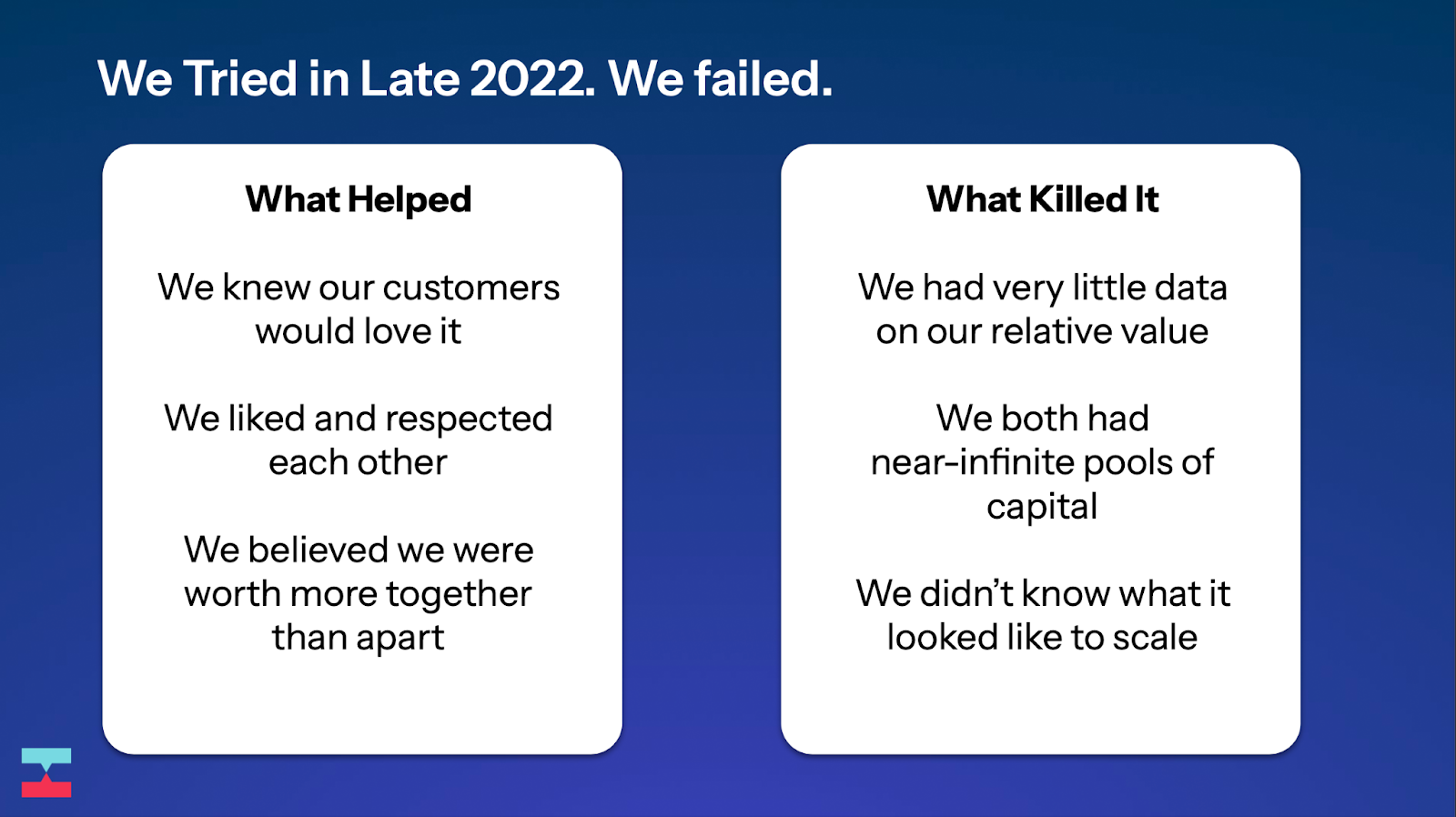

The next week, we were on the phone exploring what it might look like to try and bring the companies together. As good as the idea was, the timing was awful:

- Both companies had raised capital within the last year and still had an overwhelming majority of that capital on our balance sheets. We felt internally — and knew our investors felt — like we had an obligation to duke it out and “win” the space.

- We didn’t have a good basis on how our companies could be valued against each other. We both knew the ZIRP-era valuations were not defensible, and our ARR was changing so rapidly that it became a battle of whose forecast was more aggressive.

- It was very difficult to articulate what success would look like, mostly because we didn’t have enough post-revenue operating history to compare it against.

We mutually decided to stop talking and regroup in a year if we thought it was worth another conversation.

One year later: the deal rises from the dead

In the following year, both Crossbeam and Reveal grew revenue at triple-digit percentages — but still missed all of our ambitious targets while burning huge amounts of money. Our burn multiple was 5.9x, and we still hadn’t made strides in winning large enterprises or more complex deals with higher ACVs. NRR (net revenue retention) was under 100% as customers hopped between platforms in the midst of the market fog, meaning our buckets were leaking into each other like a snake eating its own tail. Meanwhile, customer value was often hard to prove as the networks further fragmented and implementations stalled.

Crossbeam had strongholds in analytics, cybersecurity and ecommerce, with big logos like Snowflake, Okta and Shopify in our network. Reveal had the EMEA market and had picked up huge logos in CRM, HR tech, and customer experience like HubSpot, SmartRecruiters and Qualtrics. Meanwhile, a far greater number of companies were using both of our products in free tiers. We were so distracted playing small ball with each other that we couldn’t put together the bigger play of landing large, cross-functional, horizontal deals.

The top piece of customer feedback for both companies was simple: please, please, please integrate the networks with each other. In other words, merge.

Almost a year after our last attempt, I dropped Simon a WhatsApp message: “Worth catching up?” We both knew it was time to get serious about what it’d look like to combine our companies.

Simon and I decided we had to meet face-to-face and get more time together before advancing the deal. Simon caught a flight from Paris to Philly.

In that meeting, we found the conversation kept gravitating to two sets of stakeholders: our customers and our teams. If we did this right, we could go from a “one plus one equals two” to “one plus one equals ten.” But it would require a lot of extremely hard decisions, conversations and an abundance of clarity both internally and externally.

Once we had agreed to pursue this idea seriously, one of the first things we did was create a set of “core values for the deal.” These were a set of principles we agreed to live by in the process of navigating this complex experience. If there was an argument, a stall, a blow-up or any confusion, we would look back to these values as our guiding light:

1. Customer experience wins

- What it means: Every decision should make this merger feel positive and valuable for users, even if it’s harder for us.

- Why it’s important: Our customers have to feel this is great news or the narrative — and loyalty — will turn against us.

- When it’ll come up: In messaging, customer communications, migration experience and pricing or packaging choices.

2. One company

- What it means: Once we merge, there’s no “Crossbeam” or “Reveal” — just one team chasing a single north star.

- Why it’s important: Scorekeeping or protecting old ways will slow us down and fracture the culture.

- When it’ll come up: In merging products, brands, leadership structures and shared tools or processes.

3. Frontload internal pain

- What it means: Do the hard, uncomfortable integration work immediately instead of punting problems forward.

- Why it’s important: We need to make this our hardest year so the next five can be our best.

- When it’ll come up: In restructuring teams, merging systems and tackling tech or UX debt early.

4. Focus on the future

- What it means: Tell a story about where the new company is going, not just how the old ones combined.

- Why it’s important: This moment gives us outsized attention — so we must frame a big, forward-looking vision.

- When it’ll come up: In launch announcements, motivating teams and pitching investors or press.

The values were written in intentional order, with higher values taking precedence when trade-offs emerged. For example, we wouldn’t steamroll too fast in creating “one unified company” if it came at the expense of the customer (because the customer value came first).

As you can see from the spirit of the values, Simon and I also knew we’d have to make the first year of the merger the hardest one, so our next five could be our best years. To do that, these values would help us eliminate the “let’s do both” compromises and project a clear vision for what a combined company could become. That means no co-CEOs. No naming the company something ridiculous like “RevealBeam.” No made-up titles to protect egos and bloat the leadership team. We would put down our egos and rip off band-aids as early as possible to avoid pain later.

Getting it done: from term sheet to close

Simon and I had a handshake deal, and a good understanding of what it would take to finish the job. But there was one big hill to climb: investor support.

We knew that getting our respective boards to support this move would mean coming to them with the right economic model. Our boards are made up of amazing, founder-friendly investors but it’s still their job to ask hard questions and push to optimize terms in situations like this one.

Equity ownership

This would be a stock deal, so the big question was, “How do we value each company?” To me and Simon, the data told the story: If you compared our ARR, the split was 70% Crossbeam, 30% Reveal. If you compared the size of our networks it was, miraculously, also 70/30. And the post-moneys of our last VC rounds? You guessed it: 70/30.

In keeping with our deal values, Simon and I felt this 70/30 split was the only answer that wouldn’t come with massive amounts of posturing and distraction. Predictably (and responsibly) each of our investors felt differently:

- Reveal’s investors felt they should fetch a premium as they were the smaller “target” and had an excellent alternative path of just continuing on without us due to their strong cash position. They wanted something more like 60/40.

- Crossbeam’s investors felt we should fetch a premium as the larger “category leader,” with more big customers and revenue scale. They wanted something more like 80/20.

This is where founder conviction is a superpower, and great founder-friendly investors show their true colors. Simon and I agreed that, rather than fighting each other, we would both go back to our respective investors and make a hard case for the 70/30 terms.

Bringing two companies together is an exercise in prioritizing the interests of your future combined company over your own egos and short-term interests.

A few scenario models later, we were able to get our investors convinced that a local optimization here was not a hill for anyone to die on. This would either work or not, and getting entrenched in arbitrary negotiation about a premium calculation could be a poison pill. After a week or so of meetings and analysis, the investors were all on board and the split was set at 70/30.

There’s another truth underlying the deal: because both companies were well capitalized, by joining forces, our combined cash (with cost reductions) gave us lots of runway. Crossbeam received about $25M out of the deal, which was material, especially given we’d be burning a fair amount of cash as a combined business. Even if things didn’t work out, we and our board understood that this was also effectively a fundraising event, providing a helpful downside insurance against the integration failing somehow.

Board structure

We were fortunate that many other potential landmines were easy — Simon joined the board along with one of Reveal’s lead investors. We kept my seat and Crossbeam’s three investors, and left an independent seat open. This created a voting power ratio that worked out to 67/33 (if you squint, that’s beautifully similar to 70/30!).

Investor rights

The other pill that Simon and I agreed to swallow was stacking up the liquidation preference on the capital raised by the two companies. This ensured downside protection for all the investors who would suffer dilution from this deal. Everyone played nicely here and we ended up with a really clean stock structure with 1x convertible preferred investor stock. (In other words, no new punitive investor terms or special treatment for anyone in the investor classes. Like me and Simon, they all agreed to “be in together” to make this deal doable.)

Getting to signature

Believe it or not, ALL of this was in the term sheet. Again, in the spirit of the deal values, we ripped off all these band-aids in advance so nothing could get us stuck in the closing process. It made for a protracted term sheet negotiation but a beautifully smooth and short closing process.

From the date we sent the first term sheet draft over (January 18, 2024), it was just under two months to the signing of the document (March 16, 2024).

The journey from term sheet to closing the deal

Signing a term sheet (more formally known as a Letter of Intent) is not the same as closing a deal. The term sheet lays out an initial understanding of how a deal will be structured, but it simply kicks off an intense “due diligence” period during which definitive documents are negotiated, additional discovery is conducted and more. Countless deals die during this phase, despite the best intentions laid out in their term sheets.

Here’s what our target closing timeline looked like the day we signed the term sheet:

- Term sheet signed: March 16

- Rough financial model finalized: April 5

- Org chart finalized: April 30

- Target close and signing, and external announcement: May 15

Despite this optimistic target of a 60-day close, we closed the deal at exactly the 101-day mark on June 25th. What took so long?

Lots of the delay lived in the intricacies of merging two companies with multiple sub-entities spanning the US, UK and EU. Ensuring no punitive tax consequences, stock option value destruction or currency issues was a complex journey.

The other major topic at hand was compliance. Both our companies were quite small and had plenty of other competitors to deal with in our broader market, but it was still critically important we not run afoul of any laws or even best practices particularly regarding competition. The big thing here was the concept of “gun jumping,” which is the act of operating as a combined company prematurely. It’s a little bit of a logic trap: Obviously we wouldn’t be able to execute a merger without deep knowledge of each other’s businesses, but we couldn’t share operational “secrets” like customer lists or jointly make decisions about the company's future operations until we were all one company.

Our solution was to create distinct subteams in the closing period between term sheet and the deal being done:

- “Clean Teams”: Special teammates on each side privy to more detailed information for the exclusive purpose of due diligence. They were not allowed to use information to assist the Deal Teams in their work. This included:

- Crossbeam: General Counsel, Head of Finance and CISO

- Reveal: Chief of Staff, CFO and VP of Human Resources

- “Deal Teams”: Operating executives inside each company who were “read in” on the merger and conducting information gathering to ensure a successful transaction and post-merger integration, but not privy to secrets from the other company and not engaging in any joint operational activities. This included:

- Crossbeam: CEO, CTO, CMO, VP of Product, VP of Sales and VP of People

- Reveal: CEO, COO, CTO and CPO

While the deal teams were “read in” at a high level, no competitive or sensitive information was shared and the two companies operated at arm’s length until the deal was closed. This is a really tough and delicate balance but important to avoid operating as one company until the deal is finalized.

One fun note: Like all good deals, this one needed a codename just to provide some cover in case any documents or other materials leaked. I chose “Project Waterboy” — a term inspired by the fact that my name is Bob (or Bobby) and Simon’s last name is Bouchez (or Boucher) — Bobby Boucher is Adam Sandler’s character in The Waterboy.

Coming together: day zero

On closing day, each company held their own “just us” all-hands meeting where the founders explained the deal, talked about the decision and motivation and then invited the other founder in to meet the company.

Then, the next morning (afternoon French time), we held our first combined all-hands meeting as a united company. This was possibly the most important hour of this entire experience, and we covered a lot of very important topics to set us off on the right foot.

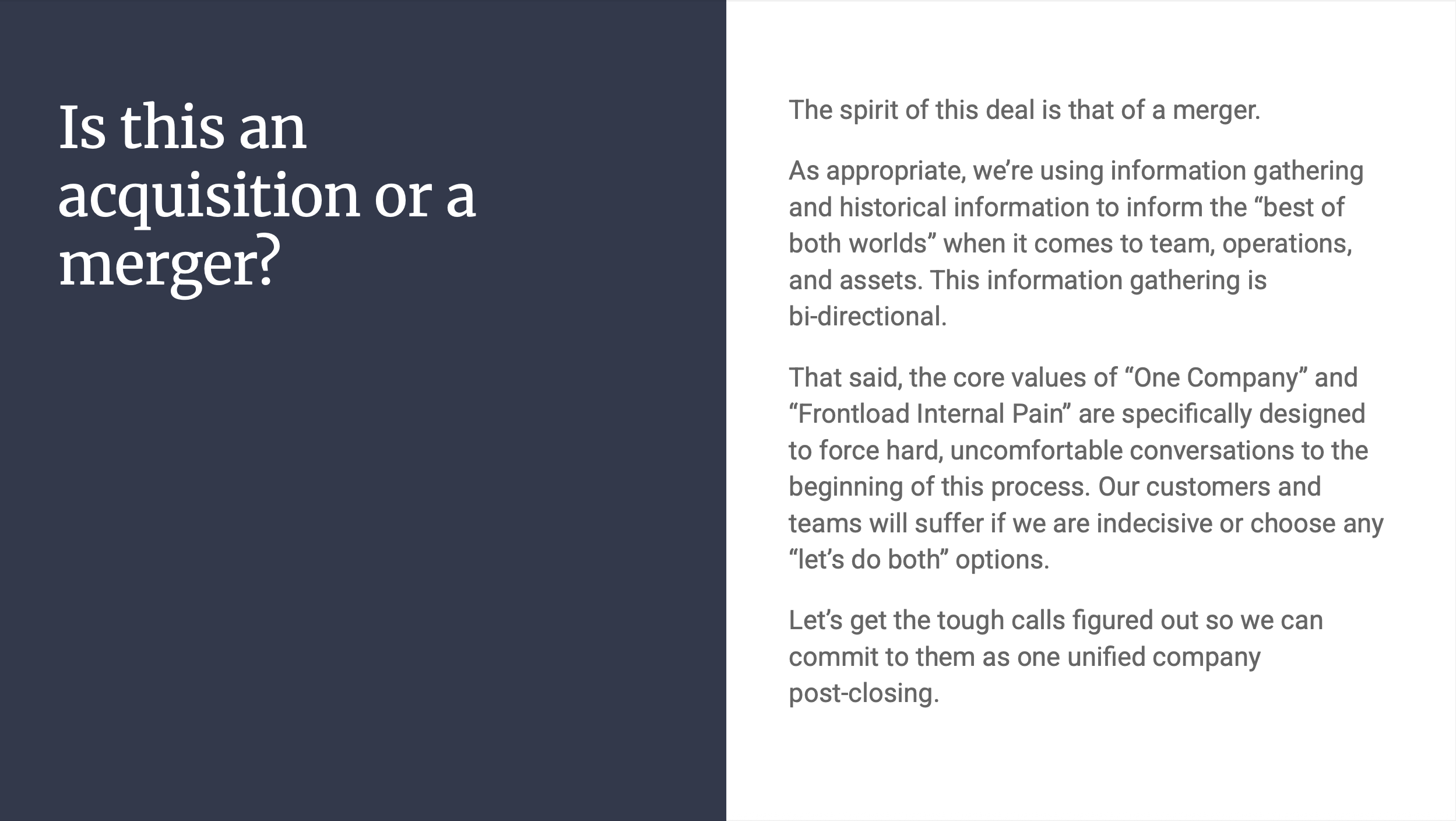

Messaging and narrative: “merger” versus “acquisition”

So much of this deal’s success can be chalked up to “not letting egos drive.” While structurally this was an acquisition of Reveal by Crossbeam, Simon and I would only refer to it as a merger.

This decision came down to the very first core value of the deal: customer experience wins. Reveal had over 10,000 companies on its platform that would be migrating over to Crossbeam (more on that later), and the message we wanted to send was one of thoughtful and equitable treatment of every customer regardless of where they had started out.

Here’s an excerpt from the announcement we sent to customers:

“We are thrilled to announce the merger of Crossbeam and Reveal into a single entity. Everyone will be able to partner with everyone. Finally.

The combined company will hold a north star vision of creating a best-of-both-worlds customer experience that includes a single unified data network. This will allow us to drive an innovative roadmap of products for all go-to-market teams that goes above and beyond today’s commoditized world of intent signals and workflows.”

In the coming months, our users can expect a thoughtful and decisive combination of our platforms, messaging, and teams. We will combine our greatest superpowers to create something even more valuable than the sum of its parts. With the most powerful account mapping data network ever created, we help more companies win, unlock new kinds of insights, and enable the go-to-market playbooks of the future.”

Moreover, there was an important message to send to both teams: We are one company (another value) and we are equally responsible for the success of our combined company.

We would make decisions based on the best outcomes for our customers and our business, and there was no place in our go-forward plan for a power hierarchy between the businesses that came before.

This was another case where I got pressure from some advisors and even our own executives to please reconsider. To them, the “optics” of us “winning” and “sending a message to the market” by acquiring Reveal were just too tempting to pass up. But, to me and Simon, that glory would fade fast and leave the wrong operational setup in its wake.

Here’s a slide from our day zero standup meeting of the newly combined company:

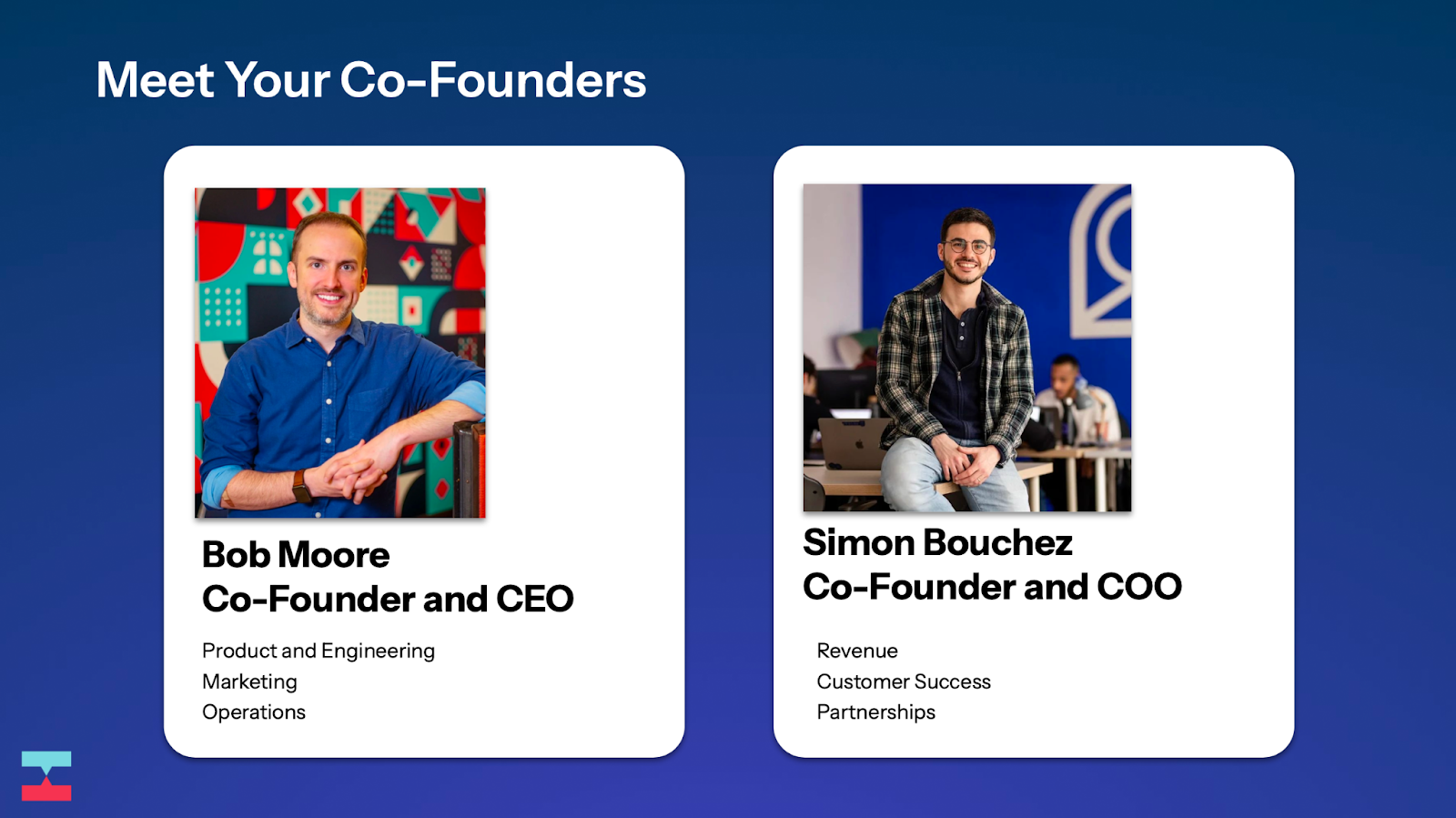

Leadership and reporting lines

Simon and I split duties along the lines of skillset and background. I’d become CEO, and because I had an engineering background (and experience as a VC and in finance), would have product, eng, marketing, finance and ops rolling to me. Simon would become COO, and had experience with more of the customer-facing aspects of the business — so sales, customer success and partnerships reported to him.

Showing that Simon and I were extremely aligned was an important part of this. In the all-hands announcing the merger, we made the new org chart transparent to everyone and also placed ourselves side-by-side as co-founders.

I want to point out one very intentional element of this new reporting structure: Simon and I ended up managing some of each other’s most senior executives, and this set an important tone around how the teams would have to immediately integrate into one cohesive unit.

Most notably, Crossbeam’s CRO, who’d previously reported to me, would now be reporting to Simon; Reveal’s COO, who’d previously reported to Simon, would now be reporting to me.

Difficult team changes

At the same time as the merger, we had to right-size the combined team (across all levels of seniority and functions). In the end, we netted out at about 120 people, down from what would have been 200 if we’d not merged and continued with our pre-existing hiring plans as independent companies.

For teammates who’d be impacted, Simon and I personally worked with them ahead of the company all-hands, with the rest of the team finding out during that all-hands. This allowed us to exit people in a way where they could retain some agency in the process, get their flowers and end this chapter in a way that connected to the successful milestone of the merger.

Defining success

We spent a lot of time in that first all-hands meeting on the deal story, the journey to the finish line, our hopes and dreams from a long-term vision standpoint. But we felt it was also essential that we define the team’s concrete measurable goals for what success would look like one year from that day.

If we did our jobs well, these would all be true in a year:

- Our company would have crossed $20M ARR (representing a material acceleration of our growth rate)

- Burn would drop to less than $1M / month (and thus combined with #1, our burn multiple would drop by over 80% from ~6x to ~1x)

- We would be one team with one (awesome) culture as shown in team retention and satisfaction scores

- We would have one product, one network, and one customer base

- The company would be spending 100% of its time on forward-looking innovation and growth, rather than artifacts or unfinished business from the merger

Now we just had to execute.

After the honeymoon: the real work

Most of the work we’d done up to this point was figuring out the deal and messaging it to our teams — but now, it was time to tackle the material aspects of bringing two companies together, most notably our products and customer bases.

Merging products

As codified in our core values, this was the highest-priority part of the merger. Our one-year goal was having “one unified product,” and within a month of closing, our technical teams had run a complex analysis of various options around how to achieve it.

The way we saw it, we had three options. Here were the two we explored, but decided against:

- Merging the two codebases to allow a seamless interoperability of the networks. This might make everyone in the room feel good, but was not the best thing to serve our customers. The backends were written in different languages, there was a ton of redundant code and we used different infrastructures (Crossbeam was on AWS, Reveal was on GCP). While it may have sounded warm-and-fuzzy to our teams and customers at first, we’d create a duct-taped system and years of baggage that would impede future innovation. We needed a clean break. (Pain up front, remember? Someone was going to have to throw away five years of their hard work and that was just a fact.)

- Creating a totally new product. We could do this, and we’d probably build a platform that was incrementally better, but we were going to spend years doing it. We’d also have to migrate all 30,000 companies across both platforms to the “new thing” instead of Reveal’s 10,000 one way or Crossbeam’s 20,000 the other way. Overall, this option felt like a short-sighted pipe dream.

We decided to have one platform absorb everything about the other (including its customers), and we ended up bringing everything over to Crossbeam.

Why Crossbeam? It had more customers (including far more large, entrenched enterprises) and a more complex set of advanced configuration functionality that would’ve been harder to map over to Reveal. Specifically, these were features that allowed customers to configure data sharing rules, user access rights and other typically enterprise-grade functionality — all stuff that would’ve been hard to spin up in a new environment and move customers to. Moving everything to Crossbeam could happen faster with less customer disruption.

It’s also worth noting that Reveal’s frontend was objectively better than Crossbeam’s. As a result, even though the combined network would live on Crossbeam’s backend, we did invest in several projects to make the Crossbeam frontend adopt the best parts of Reveal’s frontend experience as part of this year-one project.

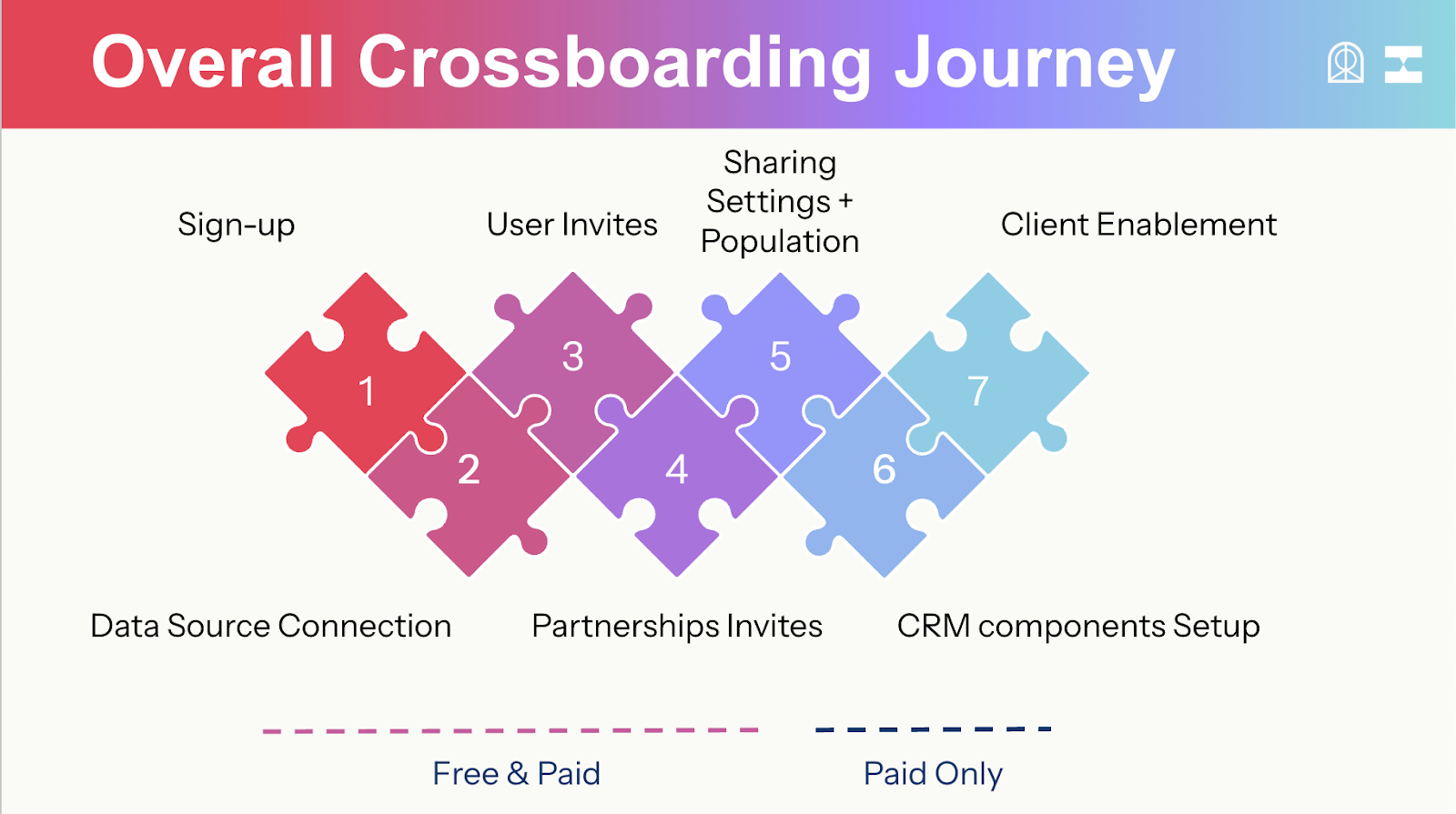

“Crossboarding” Reveal customers

We outlawed the word “migration.” No one wants to migrate anything, ever; it sounds like painful work that just gets you right back where you started.

Instead, we adopted the term “crossboarding” for the process of moving Reveal customers over to the Crossbeam network. It delivered the message that we would be there doing just as much heavy lifting as our customers.

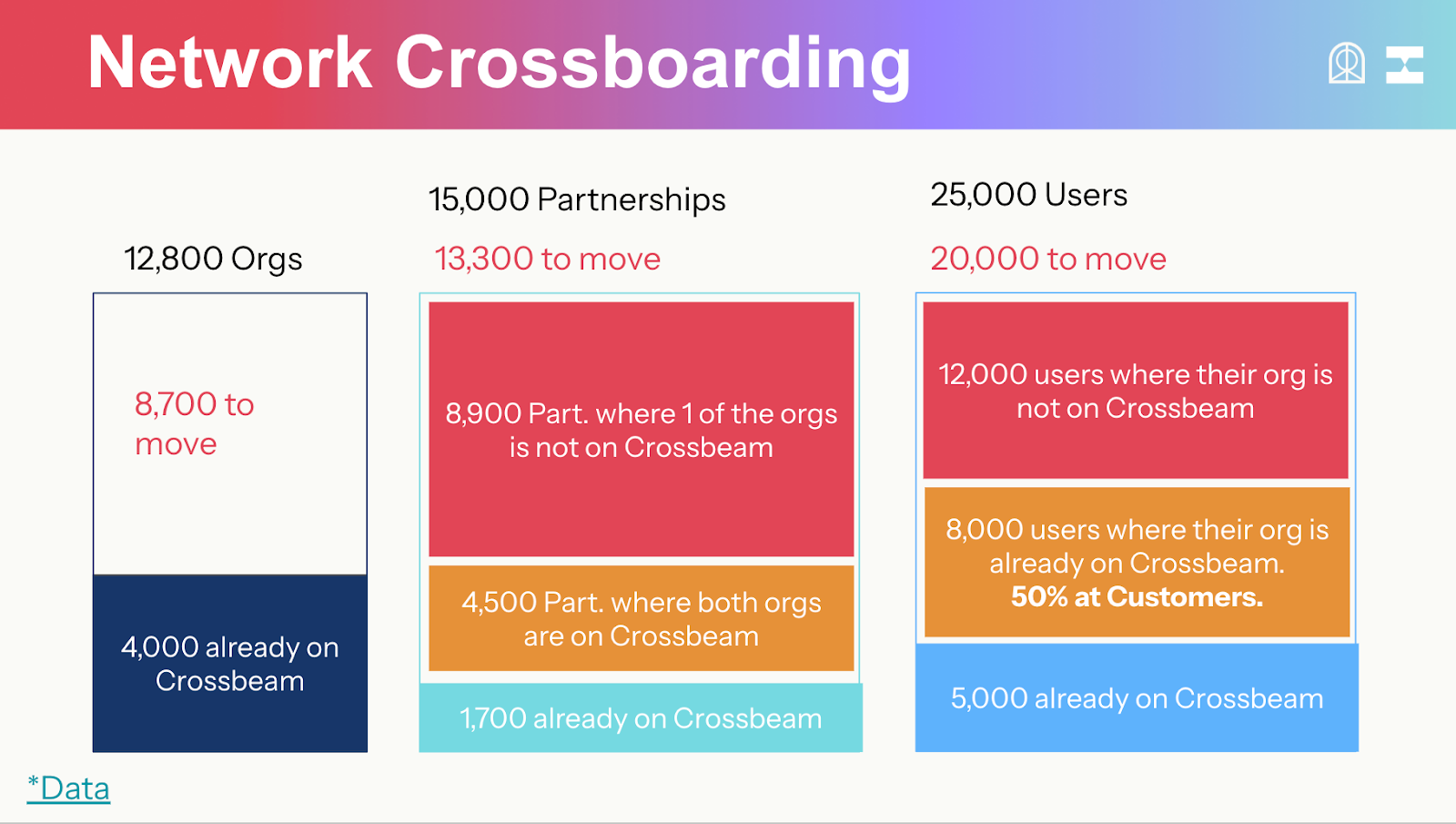

Crossboarding was a hybrid approach that combined technological work (i.e. automatically creating accounts and re-establishing partnerships) with a white glove customer service experience (i.e. trainings, live walkthroughs of reauthorizing system access). Methodically, each customer from Reveal was able to rebuild their partner graphs, reconfigure and validate data shares and navigate technical migration steps.

This required operating at massive scale (as tens of thousands of companies and users were impacted), each on their own systematic roadmap.

In the end, we crossboarded all paying customers of Reveal over to Crossbeam prior to the retirement of Reveal at the one-year anniversary of our deal. We also had a nearly 100% rate of crossboarding for active free tier users of Reveal.

Was there any churn? Of course. But interestingly, the annual churn rate of crossboarded Reveal customers was nearly identical to the pre-existing underlying churn rate prior to the merger (roughly 14% annually, or an 86% gross revenue retention rate). In other words, it doesn’t appear that the deal or the crossboarding process created any detrimental churn that wasn’t already coming our way.

Pricing and packaging

Customer migration also included getting every paying Reveal customer on a new contract that was based on “Crossbeam paper” — our master services agreement (MSA) that governs all our paid contracts.

Yes, we could have found a way to alter the Reveal MSA and create as "familiar" a renewal experience as possible for Reveal customers, but that would have violated our core values for the deal and created a lot of confusion long-term, violating our one-year goal of having all teams focused on a single, united go-to-market playbook. So we opted to make every renewal a little harder the first time so we get all customers on one clean set of books and terms. Especially for Reveal’s enterprise customers who were not using Crossbeam at all — Qualtrics, for example — this amounted to effectively restarting procurement again from scratch, an effort more akin to a new sale than a renewal.

With the Crossbeam MSA came Crossbeam pricing. Because both companies had relatively immature monetization strategies, there weren’t many large, pre-existing, multi-year contracts to untangle. We’d both been operating on freemium-heavy models and our customers had different definitions of value, forcing us to reconsider how much customers paid and why.

This was a moment to rebuild our pricing strategy on first principles. The result was collapsing the two revenue systems into one pricing framework tied directly to customer outcomes, not legacy metrics.

All new deals and renewals would be sold as Crossbeam licenses, and we’d honor the pricing of current contracts. But instead of the legacy SaaS tiers and flat licenses we were using, customers would now pay for the number of user seats they needed and what data they’d need access to — a much clearer model that more directly showed the value of the platform.

Within one year of our merger, NRR had jumped from roughly 90% to 105% and climbing. Our hole in the bucket had sealed.

Rebalancing the C-suite

Four months after the merger, Simon and I came to a hard realization: the majority of our C-suite was hired in a different era with different market dynamics, different challenges and different opportunities.

For example, most of our pre-merger marketing efforts were about category creation and standing out against a noisy competitor, but today we had a singular market story and it was time to shift energy to more pure lead generation efforts. We had also hired product and technical leadership that was more appropriate for a company many times our size (based on the high-flying ZIRP era expectations). These just weren’t befitting our new streamlined structure.

We came to the hard decision to let most of our C-suite go, including our CTO, CMO and CPO.

It became clear the new org was top-heavy. Yet our best player-coaches were thriving and hungry for more.

In thinning out the top layer of the company, we did no backfilling and instead placed more responsibility on the existing team's highest performers. These folks were given leadership positions in roles across the company, like content marketing, operations and engineering management.

We also made sure that our co-founders and remaining C-Suiters took a more hands-on approach. I was back in our daily product planning meetings, and Simon was in the pipeline reviews with our sellers. It felt really, really good — and was more befitting our size.

Reflecting back on the deal

The merger that everyone said wouldn’t work ended up beating the odds. At the one-year mark, we hit every single one of our goals:

- Clear $20M ARR — we beat ARR forecasts by 120% at one year and flew toward the $25M mark while adding ARR at a faster pace than ever before in company history.

- Burn less than $1M / month — our burn multiple plummeted from 5.9x to 1.1x in a single year and our ARR/FTE had more than doubled.

- One team, one (awesome) culture — we’d fully integrated teams and driven employee NPS up 20 points from +8 to +28.

- One product, one network, one customer base — Reveal’s product had been sunset and all customers were migrated not just to the Crossbeam platform but also to “Crossbeam paper” as every renewal in our first year was redone on the Crossbeam MSA.

- Company focused on PDE and GTM innovation — with customers migrated and Reveal sunset, 0% of our roadmap and sales energy was focused on the past. We started shipping faster than ever, and company-defining features like our Deal Navigator and AI products hit the market just a few weeks after the one-year mark.

Simon and I knew that the first year would be our hardest, and I’m extremely proud of the work our teams did and the faith customers had in us.

I can talk all day about setting egos aside or great strategic vision, but the reality is that Simon and I both knew: This deal solved the biggest problems in our companies, gave us a sense of new momentum and possibility, energized our teams and radically accelerated the hard changes we knew were necessary but feared may kill our companies.

I’ve been a founder since 2008 across three separate venture-backed companies, seen booms and busts, expansions and contractions, fire sales and windfalls. These experiences have taught me that many successful situations are a result of being lucky and good. I believe we were both, and am extremely grateful to have found a partner in Simon who had the courage to do what was right for our companies and customers. We have a lot more work to do — and now, a stronger foundation on which to do it.