If you haven’t made a resolution for 2022 yet (or you’ve already fallen off the bandwagon for the one you did select), it’s not too late to reset and reaffirm your intentions for the remaining 11 months of the year. But if typical goals like reading more or spending less time on social media are leaving you uninspired, you might be looking for something different to shake things up.

Ximena Vengoechea recommends one that’s probably not on too many resolution lists: Striving to become a better listener.

“It’s very common to have a goal to work on your presentation skills or become a better public speaker. There are tons of trainings you can take, and we’ve generally agreed culturally that those are important skills to hone. But listening is the other part of that equation — and we don't pay very much attention to it,” she says.

Vengoechea is a practiced listener. As a seasoned user research leader, she’s led and observed thousands of interviews, working at companies like Pinterest, Twitter and LinkedIn to hear more about people’s needs and motivations in order to design better products. “As user researchers, we have to connect quickly with strangers, sometimes touching on delicate topics in front of an audience. It requires asking open-ended questions, staying neutral and centering the discussion on someone else,” she says.

Tapping into more than a decade of experience doing this work, Vengoechea quite literally wrote the book on listening, publishing “Listen Like You Mean it: Reclaiming the Lost Art of True Connection” last year. The topic is, of course, incredibly timely. “These last few years we’ve all been struggling with alienation and disconnection. It’s an odd combination of feeling both isolated and then overwhelmed when we do try to connect with others. Even when we’re able to gather in person, emails, social media notifications, to-do lists and our own feelings can stand in the way of true connection and deeper conversations,” she says.

While this observation may seem particularly relevant in the realm of our personal relationships, it’s just as salient in the professional arena. “When you actually deeply listen to someone, you get to know them much better, which is going to allow you to work with them better. You're going to get greater alignment more quickly when you're able to really listen and hear out someone’s ideas, rather than just fine-tuning your own pitch,” says Vengoechea. “We often think of miscommunication as an issue with our own content or delivery — that if we could tweak the what or the how, our message would be more effective. But that perpetuates a dynamic where we view our counterparts as an audience, not as collaborators.”

Vengoechea sees listening as a skill that’s particularly important to focus on in the startup setting. “There’s often this idea in startups that speed is the most important thing. But sometimes there's such great urgency to move forward with a particular project that you haven’t heard out the rest of the team, and that's going to cause you to stumble later on because you don't have buy-in,” she says. “Or when it comes to product building, you don't slow down to actually hear what your customers need. You have the founder or product leader’s conviction that you need to ship a certain feature, but you just wind up wasting dev cycles because no one’s using it.”

So many startups are playing a game of hurry up and wait — sprinting to get somewhere only to later realize it wasn’t even the right destination. Sometimes you have to go slow to move quickly. Investing time into listening to your colleagues or getting to know your users often ends up being a quicker path to success.

In this exclusive interview, Vengoechea offers up a tactical guide for how you can become a better listener at work, wherever you sit in the startup org chart. Starting with a few fundamental skills, she goes on to offer both level and functional-specific advice that you can put to use right away. From how sales leaders can get more comfortable with silence, to how managers can better connect with their direct reports, we think every tip is worth heeding, no matter your role.

LAY THE LISTENING FOUNDATION BY WORKING ON THESE CORE SKILLS:

If you’re looking to get started with this work, the first step is building what Vengoechea calls a listening mindset. “That means you're bringing humility, curiosity, and empathy into every conversation. It sounds straightforward enough, but most of the time, we’re not intentionally coming in with that in mind. We're coming in with our own assumptions, opinions and expectations — and those can cloud what the other person has to say,” she says.

“Often we’re engaging in surface listening — hearing enough to be polite or grasping the literal sentences that are coming out, but missing the deeper meaning and chance for emotional connection.”

Most of us listen well enough, but without deliberate effort, we tend to navigate through conversations with significant blind spots. It’s all too easy for us to learn only a sliver of the full story — or misunderstand it entirely.

A listening mindset requires a bit more legwork. “You're focusing on getting curious about the other person, about what they're sharing and why they're sharing that with you. Humility requires shifting from the role of a teacher — which is how many of us come into conversation — to that of a student, where you’re trying to learn,” says Vengoechea. “And then you’re exercising empathy, trying to understand that other person's experience.”

Here are two of her quick tips to help you build humility, curiosity, and empathy into your everyday listening habits:

Tip #1: Practice mindfulness to avoid projecting.

You’ve likely caught yourself rehearsing your next sentence in a conversation, sheepishly realizing you’ve lost track of what the other person is saying. “A common surface listening mistake is getting trapped in our own narratives. We gear up to respond to something, let our thoughts wander when we’re bored, start planning our persuasive argument, or try to circle back to a topic we want to return to,” says Vengoechea.

“We also often project our own ideas, experiences or emotions onto others, rushing to tell a related story or inadvertently putting words in someone’s mouth. For example, say you’re talking with a co-worker and they say, ‘I’ve got so much on my plate.’ You jump in and try to connect by saying, ‘Oh me too, isn’t it really energizing to be on so many projects?’ when in reality, your co-worker is actually stressed by it.”

To overcome this reflex, try winding down, not up. “When a possible response or related thought enters your mind, rather than gearing up to say something or weighing in immediately, simply observe it instead,” she says. “When we’re able to table these thoughts and stop planning our responses or injecting our own beliefs and assumptions, we can better focus on what our conversation partners are actually saying in the moment.’’

The easiest place to be in conversation is in our own heads. Empathy can be the antidote to our tendency to project — we do not need to share in others’ direct experience, we just need to imagine it.

Tip #2: But remember it’s not not about you.

That said, listening isn’t entirely about the other person. “As you start trying to become a better listener, you’ll realize that much of it revolves around you and your reaction — if you’re finding someone boring, that’s on you in a way,” says Vengoechea.

“Listening is not simply about staying quiet, nodding along and just being a vessel for what the other person has to say. It’s an active process — not a passive activity. Doing the work to figure out how you tend to show up in conversations, putting in the effort to get curious and ask questions, observing cues and body language and going out of your way to include others all requires work on your part.”

It’s easy to assume that listening is merely about showing up and paying attention to the other person, but it’s also deeply tied to paying attention to ourselves.

LEVEL UP YOUR LISTENING SKILLS: ADVICE FOR EXECS, MANAGERS & ICs

Below, Vengoechea takes us through different layers of the org chart, sharing tips tailored to the unique listening challenges at different levels.

For founders and execs:

The higher up you are in an organization, the more folks you have hanging on your every word. But as your purview expands, information flow and connection to the rest of the team tends to constrict. Certain meetings fall from your calendar. Decisions you used to be involved in drop off your radar. You have less of a pulse on how the rank-and-file are feeling.

“One of the common challenges is figuring out where to lean in and where to lean out. What do you feel comfortable delegating to someone else to be the listener for and what do you really need to be there for?” says Vengoechea. “But as you make these decisions on where to focus, know that it will be really obvious to people when you're not listening. Everyone can tell when an executive has clearly deprioritized something. Making sure people still feel heard by delegating and clearly communicating about that is important.”

Especially as a company scales, you can't be in every conversation. Just realize that folks will take notice of where you do spend your listening time.

Another common challenge is feeling out of the loop, especially when bad news doesn’t seem to be winding its way to the top. “How founders and executives respond to information that's coming their way is going to dictate what information comes their way in the future,” she says. “If an exec is really enthusiastic about a new product idea, everyone around them will surface it more often. If a founder looks bored when you talk about retention, or they get mad when you talk about missing targets, then folks will not bring it up as frequently.”

This also spills over into shutting down creativity. “If you come into a conversation and always have all the answers or constantly chime in with your opinion, that doesn’t create the safest environment for people to test out different ideas or bring you half-baked proposals. You may truly want to engage more in that collaborative back and forth, but by virtue of coming out swinging, you've shut down a conversation.”

As a leader, pay attention to how your own response is closing off a set of conversations.

In addition to spending more time quietly taking in others’ perspectives before offering your own, getting a second set of eyes can be helpful. “Ask long-tenured employees or fellow executives, ‘Hey, when you observe me in meetings, what could I do to respond to others more productively?’ Or ‘I've noticed that I don't get information from this team about this topic, why might that be?’”

For managers:

Match your mode to the moment.

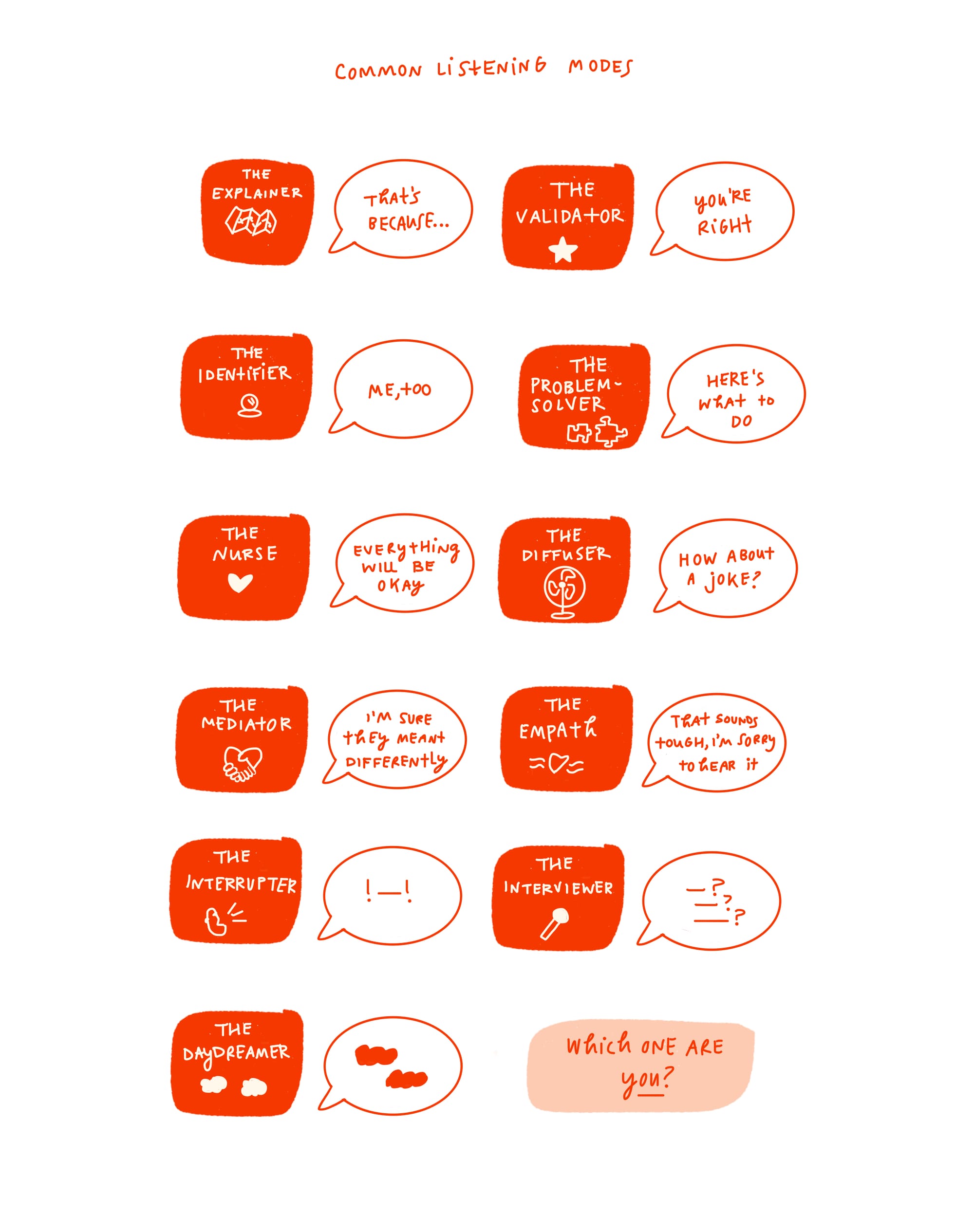

“When thinking through how you can show up for your direct reports as a better listener, it’s important to remember there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. But one tool that can be helpful is identifying your default listening mode,” says Vengoechea.

“It’s the natural filter that you tend to use when you show up in conversation. For example, you come in with a mediating listening mindset, where you're listening for everybody's role in a certain situation. Or you might have a validating listening mode, where you’re looking for ways to affirm the other person,” she says.

“Each of these modes have their ups and their downs. The key is to identify yours and then gut check yourself to see if that's what's needed in a particular conversation — or if you need to switch up your style,” she says. Here’s an example: “Say you’re naturally coming in with a problem-solving listening mode. In a 1:1, you’re scanning for problems and solutions. But when a direct report gives you an update of all the things they’re working on, you might hear that as, ‘Ah, they have too much on their plate, I have to take something off,’ when in reality, they might have been sending a message like, ‘Hey, look at everything I'm working on. I'm proud of that — and I want to make sure that you know.’ In that case, your helpful problem-solving will likely feel like micromanagement.”

Being an effective listener is about building self-awareness around how you naturally show up in conversation.

Here are a few pointers for putting this into practice:

- Take this quiz to do a deeper diagnostic of your default listening mode.

- Vocalize your gut. “You can even say to your direct report, ‘Normally, my instinct here would be to offer you advice — is that what you're looking for?’ Sometimes being willing to say, ‘Even though I’m the manager, I don't necessarily know the right response here — what would be useful for you?’”

- Open up space. “There’s power in asking ‘Would you like me to listen, or brainstorm solutions with you?’ Sometimes they just want to vent and it’s cathartic. As a manager you may hate it, and it can be unproductive if it happens too often, but occasionally creating space for that is part of your role.”

Deepen the conversation to avoid the doorknob moment.

It’s easy for 1:1s to fall into a familiar rhythm, one where you never stray too far from the surface and the more uncomfortable things go unsaid. Vengoechea has seen this challenge crop up for managers time and time again.

“As you build a relationship with your direct report over time, it’s important to pay attention to patterns. For example, in therapy, clients will often bring up the most important thing in the final few minutes of a session — it’s called a doorknob comment. Right before you start wrapping up, you say the thing that you actually wanted to say the whole time, but needed the entire hour to muster enough courage. And you sometimes see a similar thing in 1:1s,” says Vengoechea.

If you’re a manager looking to deepen the conversations you’re having with your direct report, try asking this one question: “What would you save for the end of our 1:1 today? Let’s start with that.”

For direct reports:

On the flip side of that dynamic, direct reports can struggle with different issues. “The number one question I get from folks who’ve read my book isn’t about how to be a better listener, but how about how they can be heard and deal with folks who won’t listen to them,” says Vengoechea.

Summoning the nerve to speak up is only one part of the equation. “The importance of being crystal clear with your message is often overlooked. Sometimes we really think that we have asked for help, but usually we don't do so explicitly. We don't say, ‘I desperately need you to take a project off my plate, I am drowning.’ Instead we say, ‘Well, I have all these projects, and it's tough but it's okay, don’t worry about me,’ secretly hoping our manager will say, ‘Oh, that sounds like too much,’” says Vengoechea.

“The best thing that you can do to get your message across is to be super clear and use simple language: I need help with X, I’m unhappy with Y, I'm struggling with Z.”

Often, we think that we are expressing our needs clearly and we're actually talking around them. The most direct path to being heard is to communicate our needs explicitly.

TACTICAL ADVICE ON BECOMING A BETTER LISTENER, BY FUNCTION:

Below, Vengoechea walks us through some of the pitfalls and listening challenges folks in different functions can encounter, sharing tips that will help you level up in your own domain:

Product:

Product leaders face a wide array of challenges rooted in listening, from removing the bias of their own product vision, to effectively shepherding internal teams to ship a product, to learning all that they can from users. We’ll tackle each one in turn.

Keeping your own bias at bay:

Take the common scenario of a PM at an early-stage startup who’s conducting their own customer research. “The way you structure your questions is crucial. Everyone can fall into a pattern of asking leading or biased questions, but it’s particularly acute for PMs given the nature of their role,” says Vengoechea.

“An example of that would be saying, ‘I'm going to show you two screens. Which screen do you like better, screen A or screen B?’ This sounds perfectly fine, except that it implies that the user likes one, whereas they might hate both of those screens. Many participants have a bias of wanting to please the interviewer, which gets you a less-than-honest answer. So shifting away from close-ended questions to more open-ended questions — ‘What do you think about these two screens?’ — is a small example of being aware of your impact in a conversation.”

Influencing internal stakeholders:

When attempting to win over engineers and designers internally in a product roadmap battle or under the pressure of a deadline, the PM faces a different challenge.

“In user research, there’s a very common concept that whatever you're designing has to meet a core need. Those needs can be obvious and explicit, but often they're latent and underlying — you have to tease out what's happening. Listening for those needs is crucial in user interviews, and also in getting product alignment—especially when you’re depending on a group of stakeholders from different teams to get something out the door,” says Vengoechea.

“Shifting out of the product org perspective can help you get a better sense of what your internal partners are facing. Phrases like ‘We’re working as hard as we can,’ or ‘We’re running out of steam,’ or ‘If it were up to me,’ might be clues of a need for recognition, a need for more resources, a difference of opinion, or a lack of alignment.”

Everybody is always bringing a need into a conversation. The product managers who can spot those cues will solve the internal challenges they face much faster.

Maximizing what you can learn from users:

“PMs have this interesting role where they have to understand the user but they also have to understand the market, the sales team, the technical requirements, the strategic vision. And because you’re the go-between for all these different departments, you spend a good chunk of your time explaining or convincing,” says Vengoechea.

“But toggling out of that teacher mode is important. Let's say a user doesn't understand a flow or the purpose of a feature. PMs might have a strong impulse to override and say, ‘Oh, well, this is how it works,’ or ‘This is how you would use it.’ Then the user thinks to themselves, ‘Oh, okay, I wouldn't use it that way, but I'm probably not who you're designing this for.’ Now you’re missing out on that valuable feedback. Step back into that student mode and enter into every session with a learning mindset. Ask yourself: The fact that it's not obvious to this person, what does that tell me?”

Product managers are used to explaining the product and their vision to all these different parties. But when it comes to interviewing a user, their job isn’t to explain, but to listen and learn.

Design:

“One of the listening challenges for design functions is that because they have created the experience or prototype that we're putting in front of people, the feedback can feel much more personal,” says Vengoechea. “When things feel personal and when our ego is involved, it gets really hard to listen.”

In the book, she describes these as hotspots — emotional areas and tender topics in conversation. “It could be something taboo, or a more personal danger zone, anything that makes you feel more emotionally charged and overpowers your efforts to listen with empathy. In the case of a designer, it’s often all of the hard work that they put into this design. Maybe they had to fight for their vision with the PM, or they feel like they have a lot on the line in terms of their career progression,” she says.

“If someone says something that rubs against your emotional attachment or ego in some way, it can be hard to hear that out. It can be easier instead to rationalize why that person is wrong or to dismiss it outright. That might look like shutting down, reacting defensively, or getting demoralized.”

The antidote? Start by recognizing the pattern. “Just acknowledging, ‘Oh, I'm having an emotional response to this,’ or ‘I'm feeling bad about that feedback,’ can be powerful. Noticing how you physically feel in your body, which is where often we feel it first, is also helpful. Are you feeling a tightening of the throat, or a pounding of the chest?” says Vengoechea.

“When you can tune into that and then label it, that helps diffuse the feeling. Try phrases like, ‘I'm having a strong reaction to what this participant is saying about my designs, but this is not actually about me right now,’ or ‘I'm feeling a little bit attacked in critique today, but I know that's not what my peers are trying to do.’ You can even say, ‘I'm super activated right now. I need a five-minute breather, and then I'm going to come back to this conversation.’"

UX research:

UX researchers may already be strong listeners, but even on her home turf, Vengoechea acknowledges there’s always room for improvement.

“One of the things that you see, particularly in early-stage researchers, is a real attachment to the moderators guide which has your list of questions. There's a strong sense of, ‘If I hit every question, I will get the insights I need.’ But when you're so focused on that script, you actually are not listening as much to what's happening in real time. You're not able to pivot and respond to what’s being said,” she says.

“If you can use your set of questions as a guide, not a script, you can really pay attention to what someone is saying in real time. That’s where you can follow them down potentially productive tangents — which is where the insights are going to come from.”

For the more seasoned UX leaders, Vengoechea flags a different hurdle. “If you’ve been in a certain domain for a while, you build up expertise, which of course can be incredibly valuable. But there comes a point where you start to predict the responses that you hear in sessions. I worked with advertisers, developers, consumers and found that point with each audience,” she says.

“But if I come in with the attitude of ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, I know this already,’ I'm not going to get anywhere. That’s going to show up in how I ask my questions, in how much time I give participants to respond, and I'm going to only confirm what I already know,” she says. “For example, I worked with many SMBs and got to know their problems — they lack resources, time, money. But if I went in thinking it would be an easy interview, I’d likely learn exactly those three things. Instead, if I went in and thought, ‘What else? Or to what extent? Or in what ways? Or when is it worse? When is it easier?’ then that would be a different conversation.”

You have to be able to bring in your expertise as a way of deepening the conversation — as opposed to flattening it.

Engineering:

“Engineers don't always get credit here.I've worked with many very user-centered engineers. There are tons of very creative engineers who have ideas for products, features, or user research, and are great at listening to their counterparts on other teams,” Vengoechea says.

“For engineers, getting empathetic and curious can give you a better sense of how the rest of the org works. In the context of learning from users, it can also make what you’re building feel less abstract, especially if you're on the back-end and it’s not immediately obvious how what you’re working on is going to show up in someone's everyday world.”

If this is a skill you want to work on, here’s her recommendation. “Engaging in a big listening tour to talk more to other teams, or interacting with users directly in research sessions or sales calls is one way to build this muscle. If that’s not your style, start smaller.

“As an initial step, I would think about listening not just in terms of what you're hearing, but also what you're seeing. You can practice in quiet, unobtrusive ways in a meeting by going beyond the actual work being discussed and observing the overall group dynamics. What's being said, and what's not being said? Whose opinion is being repeated, whose opinion is being credited, whose opinion is being ignored, and why might that be?”

Sales:

“With sales, you have a very clear goal: You're trying to close a deal and sell your solution as the solution. That means you've already got a certain listening filter in place. You're scanning for which part of a potential customer’s problem your team can solve — or if you can reframe that problem into something that you can solve. But if you're not careful, then you're going to miss the actual problem,” says Vengoechea.

Leading with discovery around their problem, as opposed to selling your solution is a good place to start. But she also has another recommendation for folks who spend their days talking to prospects: Embracing silence as a technique.

“This can be counterintuitive because we think of silence as particularly awkward, or a sign that we're not connecting. But asking someone a question and giving them the space to respond is an underutilized tool. Taking a beat before you chime in with your pitch, or waiting a hair longer than is comfortable before pivoting toward your solution will usually yield something insightful,” she says.

“This is a technique that we use in lab sessions. If you’re naturally impatient, just count to 10 in your head. You probably won't even make it to 10 before the other person chimes in.”

Create more space for people in your conversations. That awkward moment of silence usually takes place just before some nugget of truth or stroke of insight spills out.

People team:

Folks on the people team have to do a lot of listening, especially these days. But of course, there are nuances depending on your specific role.

For recruiters trying to close a candidate:

Spend more time asking more questions than pitching. “Sometimes there's a dynamic with a recruiter of ‘I'm going to sell you the company, the vision of where we're going to be in five years.’ But when you’re in sell mode, it’s easy to overlook the power of slowing down and asking more questions of the candidate to get a sense of whether it's truly going to be a good fit, especially in today’s competitive market.”

When it comes to recruiting you can always tell someone what they want to hear, but within six months you'll both know whether it's true. Listening for what a candidate is truly looking for instead of just pitching will save you wasted cycles.

“And I understand the impulse, you've got headcount quotas that you want to fill. But taking your time to make sure that the person is a good fit will save you from having the same conversation six months from now because it wasn't a good fit,” she says. “That means doing your best to slow the conversation down, creating more space through silence, and maybe asking another question when you have an instinct to pitch. My go-tos are questions like, ‘What are the toughest parts of your job? The easiest? The most exciting?’ These are open-ended enough that answers can cover anything from resourcing constraints, to office politics, to the nitty gritty of the core job.”

For people team members navigating tough conversations with employees:

In the past few years, people teams have been handling hard conversation after hard conversation, whether it’s around layoffs, remote work policies, or supporting employees going through challenging times.

“When you're having a particularly emotional conversation, make sure that everybody's getting whatever breaks they need. There's a sense that we just have to deal with our emotions in the business world, that we can’t cry or interrupt this meeting with our feelings. But we're all human and the pandemic has really reaffirmed our humanity,” she says. “It's okay to ask for a pause if you need to. It's also okay to do this on behalf of someone else, and empathetic listening helps clue you into that. Asking, ‘Hey, do we need to pause for a minute?’ or kindly making an excuse like requesting a bio break so that you are hitting pause on their behalf can be tremendously helpful.”

Another tip is to get comfortable with inaction. “Sometimes when we're having emotional conversations, there’s no action that needs to be taken, which is hard for us to sit with because we often feel that we have to do something, whether it’s solving the problem, giving advice, or moving the ball forward. We expect a certain momentum in conversations,” says Vengoechea.

Sometimes there's nothing to do except just to listen and bear witness, to give that other person the space to have whatever strong reaction or difficult opinion they may have. Always remind yourself that that’s an option.

Of course, several years of conversations like these have left many leaders feeling drained. “Recharging and recovering from empathetic listening boils down to processing and sharing your experience in some way. That doesn't mean you need to go shout it from the rooftops — for some of us it feels really good to process this in conversation with others, for others that sounds terrible and solitude is going to be much more restorative instead,” she says.

“When you have that tendency to play that empathetic ear, usually you do that everywhere — at work and at home. Some of your relationships may even be defined by that. That might mean you have to practice distancing, setting boundaries, and politely ending a conversation. If you're finding that some of those relationships are really off kilter or maybe someone is really taking advantage of that empathetic ear, starting to exercise self-advocacy is important.”

When we listen without having our own needs met, we risk becoming listening martyrs — repeatedly putting others’ needs before our own in conversation, which puts our sense of self and connection to others at risk.

Cover image by Getty Images / Cathy Scola. Photo of Ximena by Kara Brodgesell. Illustrations by Ximena Vengoechea.