We’re ringing in the new year here at The Review with a longstanding tradition: sifting through the hundreds of thousands of words we published over the last 12 months to surface the very best 30 pieces of advice we shared.

Company-building today looks very different from when we started this annual tradition over a decade ago. The fundraises are bigger, the timelines are shorter, the teams are tinier and expected to do much more with less. While many of last year’s tech headlines featured record growth and eye-popping valuations, we found our curiosity drawn to the untold stories of quiet execution, scrappy experiments and contrarian bets that paved the way — starting with founders who ask, imagine if this could be different or better or faster?

We asked founders who had a banner year in 2025 to recount their companies’ early days, long before the first glimmers of product-market fit, when imagine if was all they had. We chronicled how EvolutionIQ’s founders turned an early bet on vertical AI into a $730M acquisition, how Karri Saarinen scaled Linear into a billion-dollar company by bucking the "growth at all costs" mindset and how Varun Anand tuned the gears on Clay’s go-to-market engine to spur its breakout growth.

We also shared many tactics to guide founders who are currently in that lonely 0-1 stretch. Color co-founder Othman Laraki opened up about how he went unreasonably deep to learn a market he had zero experience in. Figma’s first marketing hire, Claire Butler, offered up advice for how to launch out of stealth. Sierra GTM leader Logan Randolph shared a detailed guide on landing your first design partners.

This moment in startup time feels equally full of promise and pressure, where so much is possible but you’ve got to grab it immediately. Our mission here at The Review is the same as ever: to help make the fog of company-building a little easier to navigate. Our hope is that by spotlighting the sharpest startup builders of today, the next generation of founders can find kernels of wisdom to hang onto when so little feels certain.

With that, here are the 30 standout pieces of advice we gathered last year to help you build an incredible company in 2026.

1. Don’t take your boots off the ground

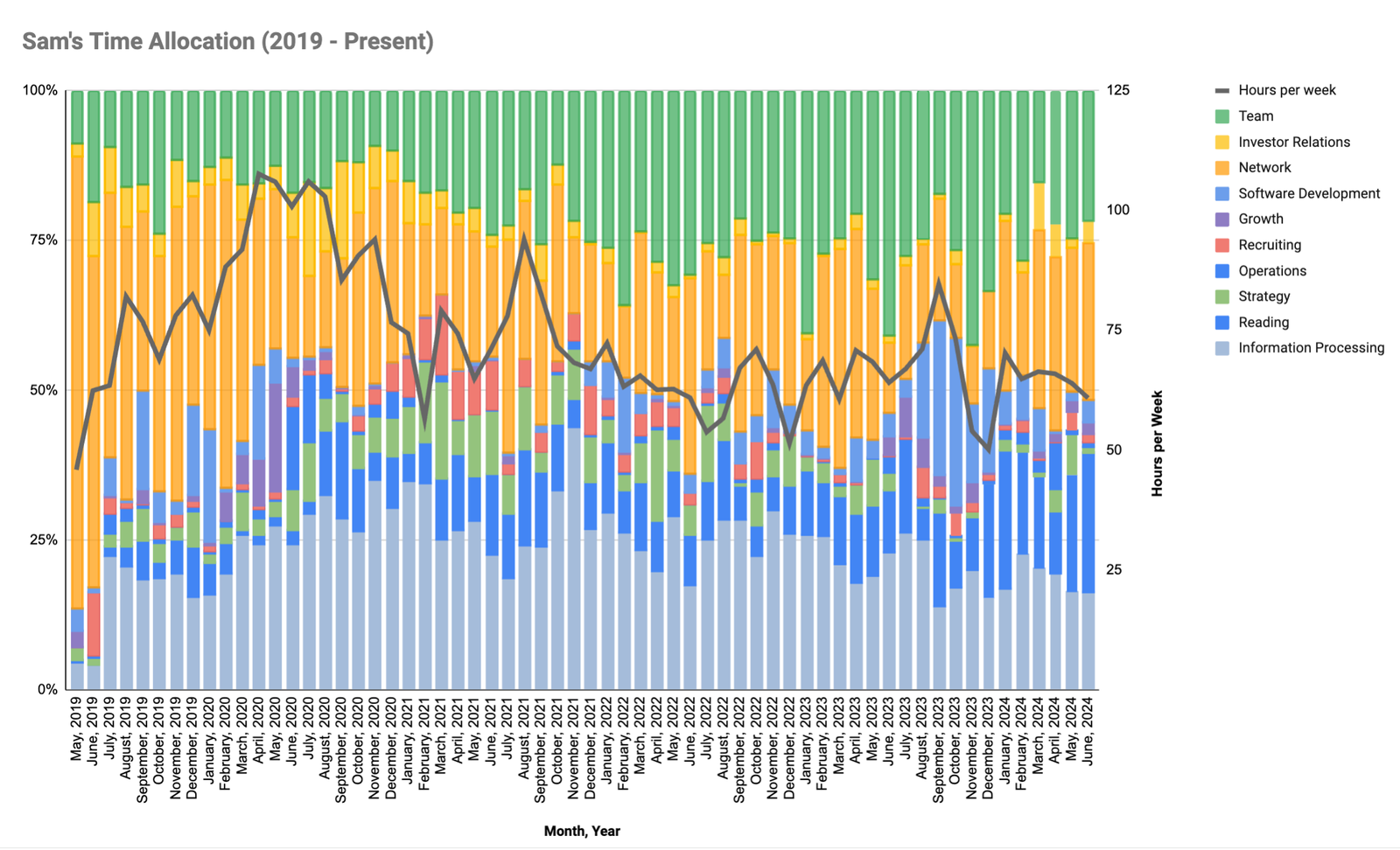

Sam Corcos tracked every one of the 17,784 hours he spent over five years building Levels, neatly plotting the time he spent on different areas of the business.

Just one of his many takeaways from his rigorous self-analysis: He took an extended hiatus from the codebase in the company’s scaling phase, and he regrets it.

In Levels’ first two years, Corcos himself often pulled tickets and shipped code, a period of software development he describes as insanely high-velocity. But as the pressure to scale came in years three and four, he felt the need to “professionalize” the engineering org and bring in PMs, designers and experienced managers. Soon, shipping ground to a halt.

“There are a lot of idioms to describe how I was feeling around this time: treading water. Pushing on a string. Screaming into the void. But looking at the data, I have no one to blame but myself. It’s easy to see from reviewing my time from these couple of years that software development was not my priority, and it should have been,” he says.

So Corcos overhauled the org and stripped its structure back down to a lean team of engineers who reported directly to him. Here’s what Corcos learned from the course correction:

- “I had lost touch with the people making and using our product. But I didn’t have the courage to do what needed to be done,” he says. “When I would make an effort to get back into the codebase and the product development cycle, or even just talk with customers again, I would hear from the leadership team that my involvement was disruptive and I should let them do their jobs. I didn’t push back strongly here, because I was too busy listening to conventional wisdom — likely because it leaves less room for criticism.”

- “I continued to place my focus in other areas of the business — which was a huge mistake. I had allowed myself to become the passenger and not the driver of my own company. It wasn't until I made the drastic change that I felt like I was running this company again,” he says.

- “We no longer hire pure ‘managers’ at Levels, and we probably never will again,” he says. “The managers we hire need to be capable of performing the tasks of those they manage. If they manage engineers, they need to be able to write excellent software. If they manage marketers, they need to be exceptional marketers themselves. Hire people who can be ‘button clickers’ instead of finding someone else to click the buttons for them.”

2. Hire more entry-level people, not fewer

New grads entering the workforce had a lot to be anxious about in 2025, with reports that job opportunities for entry-level folks are shrinking as companies invest in AI. Shopify, meanwhile, hired 1,000 interns.

CEO Tobi Lütke’s memo asked teams to see what they can get done using AI before asking for more headcount. The company has since consciously diverged from this charter, doubling down on both AI and entry-level talent. The reason, says VP & Head of Engineering Farhan Thawar, is that young people are AI centaurs: they use AI in reflexive, creative ways.

After Thawar successfully ran a 25-person engineering internship program, Lütke asked him how big they could scale the program. “Without new infrastructure, I originally said we could support 75 interns. Then I took it back. I updated my answer to 1,000,” says Thawar.

He’s led many intern programs over the years at Shopify, and has long believed new grads’ fluency with the cutting edge tech adds a lot of value to the team. This era is no different. “They’re always interested in new tools and shortcuts. I want them to be lazy and use the latest tooling,” he says. “We saw this happen in mobile. I hired lots of interns back then because I knew they were mobile native.”

3. Win hearts & minds at every altitude of the org chart

When EvolutionIQ (an AI platform for insurance claims) got scooped up by CCC Intelligent Solutions for $730M, it marked one of the first major vertical AI exits. We knew every detail of the company’s six-year trajectory was worth careful study, so we sat down with co-founders Mike Saltzman, Tomas Vykruta and Jonathan Lewin to share what they got right.

While no single decision or strategy netted this impressive outcome, one tactic stood out to us: During customer discovery, the founding team was committed to building close relationships with not just C-Suite execs who’d buy their product, but also the insurance workers who’d be using their product.

“One of the things that I think our business has done really well — and has been important to do well — is we have been good at building and maintaining relationships across the verticality of an organization," says Saltzman. “From the frontline desk person who could be a recent or junior employee, to the manager, to the director level, to the VP, to the Chief Claims Officer and the President of the business — we built relationships with everyone in the reporting line, and we adjusted our approach depending on what they needed.”

The team created feedback loops that spanned the organization. "With the frontline examiners, we were white boarding out what we could do at the desk level,” says Saltzman. “And then once a week, we were meeting with their manager, and once a month meeting with the head of claims and saying, 'Look, this is what we're hearing, this what we think we're building, does this problem work for you as well? Do you want a solution here?' We got all the stakeholders to dive into the process.”

This strategy proved effective as EvolutionIQ landed new customers. First Round Partner Bill Trenchard, who first invested in the team in 2019, says the knowledge the founders gained from wading into the details was impressive.

“They had this ability to really explain at a deeper level what was going on inside of disability insurance, and why AI was going to be a big difference maker for them,” he says. “You only develop that skill from immersing yourself in the problem and going ‘unreasonably deep’ to understand it from every angle.”

4. Embrace ego death in founder-led sales

As a long-time GTM exec-turned-investor, First Round Partner Meka Asonye has noticed that many of the founders he’s worked with have a bit of a sales phobia. “My biggest fear when I decided to start a company was that I would have to do sales,” confesses Marta Bralic Kerns, founder and CEO of Pomelo Care.

For an essay exploring the founder-led sales process, Asonye recruited an all-star bench of sales leaders and GTM-savvy founders to share their wisdom on how to overcome this fear on the path to the first few million in revenue.

One of Asonye’s best pieces of sales advice for founders is a dose of tough love: Stop talking about yourself. “As I’ve found in my own sales career, the best sales calls are the ones where you as the seller don’t talk much at all,” he says.

Mike Molinet, co-founder of Thena and Branch, has found this to be true as well. “People care about themselves — are you solving my problem or not? They don’t care about what you do and who you are,” he says.

Founder ego death means letting go of your product assumptions — and listening to what the customer is telling you, even when it’s not what you want to hear. Eric Lasker, CRO of Varda Space, puts it this way: “I’m a big believer in finding your hypothesis and trying to burn it down as quickly as possible — do as much as you can to destroy any ego you have about your product and your ability to make a sale,” he says. “The goal in the early days should be to really test if you have something the market wants, almost more than your ability to sell it.”

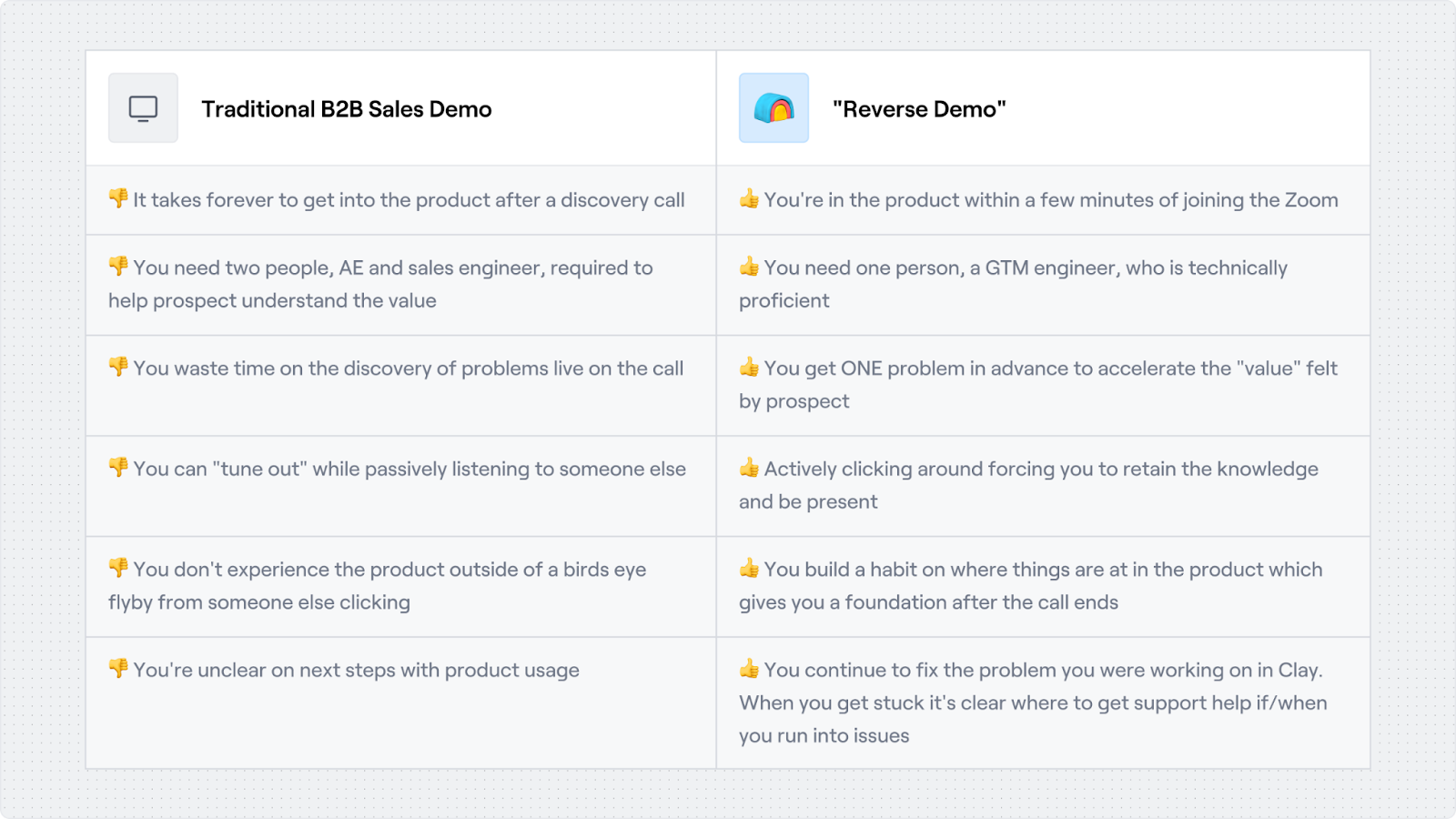

5. Run a reverse demo to spark magic for prospects

Clay’s revenue growth curve speaks for itself: 10X in 2022, 10X again in 2023, 6X in 2024, and the company recently blew past $100M in ARR.

Varun Anand joined in 2021 and quickly earned the co-founder title by building out many of the sales systems driving Clay’s growth today.

One of the more clever GTM tactics Anand shared with us is Clay’s use of a reverse demo in sales calls. Even after Clay had narrowed in on their ICP of outbound salespeople, the team still struggled to help prospects find an “aha” moment with the product. So rather than him leading the demo on a sales call as is customary, he’d have the prospect share their screen.

Anand would give folks a Clay signup link, and then use Zoom’s annotation features to guide them through which buttons to click to help solve the problem at hand. “Our goal with every reverse demo was simple: Solve the customer’s stated problem within 30 minutes — and try to blow their minds in the process,” he says.

“If you’re learning how to drive a car, you don’t sit in the passenger seat while the instructor lectures you. You take the wheel while the instructor safely guides you,” says Anand. It was a fair trade: The Clay team got a ton of UX feedback, while the customer learned how to use Clay.

6. Self-serve product onboarding should be opinionated, interruptive and interactive

The leaky bucket problem is an existential threat to every founder who’s closed their first handful of customers. You fought hard to win them — but the second half of the battle is keeping them and, hopefully, leaving them wanting more.

Onboarding is one of the best levers to pull for retention. Gaurav Vohra was the architect behind Superhuman’s onboarding experience, which is well-known for being white-glove, highly personalized and human-led. Vohra dropped by The Review to share how he designed the email app’s onboarding in full, starting with how the Superhuman team manually onboarded new customers, and later translated that experience into software for a self-serve experience.

He drew much of his product inspiration from an unlikely source — video games. “For decades, video game creators have been perfecting the art of dropping players into new and complex worlds and then setting them up for success. They teach players to learn the controls, take action, and embark on their adventure,” he says.

He discovered that the best video game onboarding has three attributes that product and growth teams typically shy away from: It’s opinionated, interruptive and interactive.

Here’s what each quality looks like in practice:

- Opinionated: “There are many ways to use your product, but there is likely a best way. And you owe it to your customers to help them down that path,” says Vohra. The team modeled an opinionated onboarding after 1985’s Super Mario Bros 1-1, pulling in design elements from how the game instructs players to learn to jump.

- Interruptive: “Great product onboardings arrest a user's attention with something important to say,” he says. To create an attention-grabbing flow, Superhuman took a cue from another video game: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, where a fairy helper shouts, “Hey, listen!” The result was a full-screen checklist to help a user get set up.

- Interactive: “A common objection to being opinionated and interruptive is that it removes agency from users. The antidote is to make these experiences interactive,” says Vohra. To do that, the team took inspiration from how early video games like Super Mario Bros teach through play (e.g., the first level gently introduces mechanics), applying a similar philosophy in Superhuman’s onboarding by having users interactively practice key shortcuts like Z to Undo Send.”

7. Founders, figure out growth before you delegate it to someone else

If you ran an autopsy of every failed startup, you’d often find a few common culprits — lack of product-market fit, mismanagement, co-founder breakups. Matt Lerner makes a bold claim about the leading cause of death: “Nearly always, a startup's failure has to do with the founder's approach to growth.”

A former PayPal B2B growth lead and co-founder of SYSTM, an online accelerator for startups, Lerner has seen this play out again and again with the founders he’s advised. Generally, the growth-averse founder falls into one of three buckets:

- The overthinkers: “Founders who debate, theorize, strategize and talk to other smart people all day long and think things through, but never execute,” Lerner says. “I don’t need to tell you how that story ends.”

- The underthinkers: “These founders’ philosophy is to build, build, build, and fair enough.” he says. “But if you’re just building off your sense of the market, and your product isn’t working, adding more features that your customers don’t need, founders are just adding complexity to the product, the code base and maintenance — and slowing themselves down.”

- The hire-and-delegaters: These are founders who come from a senior role inside a big company, or who are humble enough that they rely on hiring experts for leading all the different functions. “But those outside experts don't have the right context,” he says. “They're thinking in terms of their own function, not the entire company. The founder needs to be involved in growth at the early stage.”

“Ultimately, founders need to be the ones that figure out how their business is going to grow,” says Lerner.

Founders can't afford to delegate growth right away, nor do the best founders have to. It's in great founders’ DNA to get stuck in something and make a mess of it until they figure out what drives their business forward.

— Matt Lerner, co-founder of SYSTM

8. Rent an exec to help you build a new function

It seemed like every seasoned operator went fractional last year. It’s a newer term for a hardly novel practice — executive talent working with a company on a part-time basis. But this surge of fractional talent hitting the market has created some confusion on the hiring side.

Long-time ops leader Amanda Schwartz Ramirez offers some clarity on what early-stage startups need to know about working with fractional leaders. One major benefit, she says, is de-risking a costly executive hire while you stand up a new function or build management muscle. “Finding the perfect executive is like trying to throw darts at a moving dartboard and hit a bullseye. A fractional leader can help you understand what you need while you're figuring out what it is you're building,” she says.

But fractional execs aren’t a panacea. “I don't think that fractional is the answer for every function, especially as you build out the core product, design and engineering engine,” she says. “The question you should be asking is: Are there any industry or functional gaps that we can close to help us move faster?”

To steer clear of diluting the core product discovery process, Schwartz Ramirez recommends asking these questions upfront before hiring a fractional exec:

- Are you clear on why this person is here, and what perspective you’re hoping they will bring that informs your PMF process?

- Are there specific bottlenecks that you’re looking for an experienced leader to clear? Specific types of functional or industry expertise you’re lacking?

- Can you establish a part-time working relationship that ensures your fractional leader gets the context they need without falling out of sync every 48 hours?

9. Take a detour from management and dust off your IC skills

In 2015, David Loftesness graced The Review with his 90-day plan to transform engineers into managers. Last year, he returned with another 90-day plan for the flip side of that transition: returning to IC work.

After runs as an engineering leader at Amazon, Twitter and eero, he traded in his manager mantle and took on a role as an IC developer. He’d done this transition a couple times already in his career, moving between manager and IC engineer roles and even cycling between managing ICs and managing managers multiple times. “I just missed that feeling of shipping code,” he says, feeling a pull at this junction to get back to the ground floor of engineering.

Using his own experience of putting the IC developer hat back on, Loftesness laid out his transition plan in full, from communicating the change to settling back into a maker’s schedule. As the notion of the AI-powered “super IC” took hold last year, we found his advice particularly timely (and broadly useful to anyone considering this transition — not just engineers).

Transitioning back to IC work doesn’t have to be permanent. Throughout his own cycles, he’s found that stepping away from management can actually improve your skills as a manager. “Every time I've taken a break to return to coding, I've become a better manager. Sometimes you need to step away from the trees to see the forest,” he says.

The transition to management isn’t a one-way door. You can continue to be a leader without being a manager — they’re not the same.

— David Loftesness, former engineering leader at Amazon, Twitter and eero

10. Build for behavior change (and be realistic about the power of inertia)

In the scramble to ship vibe-coded products to market, Jeanette Mellinger thinks founders are flying past a few fundamentals. Long before you start selling, and even before you start building the product, the user research expert says founders should find problem-solution fit.

“Problem-solution fit means finding a deeper customer need that you’re uniquely positioned to solve, and building for it with better early signals and stronger team alignment from the start,” she says.

Mellinger shared her extensive user research toolkit with The Review to help founders add more rigor to the discovery phase. She calls out one steep psychological barrier every founder must climb over: user inertia. “Meaningful behavior change is required to get most products and processes off the ground, and it’s a lot harder than it seems,” says Mellinger. “This is where you bring in tools to get to know humans. We know a lot about what motivates us through behavior change models, or in this case, asking someone to read your email or try your product — to do anything different.”

Mellinger points to these two behavior change models as a framework for developing a solution in the discovery phase:

- The Fogg behavior model. Stanford professor Dr. BJ Fogg created this simple formula that results in behavior change: B=MAP. Behavior happens when Motivation, Ability and a Prompt collide at the same time. Does your customer want to use your product, and is it easy for them to use it — and importantly, do they have a reason or reminder to start using it? If you fail to get your desired behavior, you’re probably missing one of these three things.

- The Hooked behavior model. Inertia is a powerful force, and building a product people want to use more than the thing they already use is an uphill battle. Nir Eyal, who conceived this model building on Fogg’s, says that a new product must be 9X better to escape the inertia of using the incumbent solution.

Building something great doesn’t mean people will adopt it. There’s too much else going on.

— Jeanette Mellinger, former Head of UXR at Uber Eats and BetterUp

11. To learn how a market works, follow the money

When picking a market to build in, some founders choose one they know like the back of their hand, often spurred by a personal frustration. Others stumble upon a problem ripe for solving in a market they’ve never stepped foot in.

Othman Laraki is a remarkable success story of the latter path. Before founding Color, a virtual cancer clinic, he had never worked in healthcare. He was a former founder and Twitter PM who’d stumbled upon the idea for cheaper genetic testing when his co-founder, Elad Gil, got his genome sequenced (for $4,000).

To understand the inner workings of healthcare, he started with what he knew — building a product. Only in the process of learning the market, however, did he realize that a direct-to-consumer genetic test didn’t align with buyer incentives, and Color pivoted to a platform that sells to employers.

That’s why his first order of operations to learn a new market is to untangle the flow of money and decision-making. He says the best way to do this is by setting up exploratory conversations with industry leaders you might sell to, like a claims adjuster in insurance or a procurement manager in construction, for example.

“One of the mistakes I see founders make is not talking to people enough,” says Laraki. “I meet a lot of healthcare companies where you can tell, even though they’ve been in the industry for a while, they’re still naive about the marketplace. They don’t understand their buyers in a deep way.”

“As consumers, we think about one buyer and one seller,” he says. “But in many industries, with healthcare being an extra-complicated version, the process of making a purchasing decision and acting on it can be more complex. It’s worth being flexible about which buyer you want to sell to.”

“Who influences, who decides, who sets the price, who sets the terms, how the transaction actually occurs and how you get paid — this is what you have to untangle,” he says.

12. Prove you can do the hard part first

Like Color’s Othman Laraki, Immad Akhund, CEO and co-founder of Mercury, is a founder who’s proved that you don’t need domain experience to build an enduring business.

The idea for Mercury had been sitting in the back of his head for years. As a multi-time founder, he was continuously frustrated by the horrible business banking experience, even as other fintech products like Stripe and Square started to take off.

When he finally decided to pursue the idea, he knew he had to do the hard part first: learning the market. “Fintech was a completely new space to me,” he says. “I knew I could build a product. The hard part was figuring out the framework for compliance, risk and legal to make a bank sponsorship work.”

So Akhund set out to talk to three expert personas in the fintech space: founders, investors and lawyers. He had over 90 conversations over the course of four months. He came to understand that building the initial product while meeting compliance standards would require a long execution period. “I realized it might take years to get this product live. My mindset became, ‘This isn’t going to be easy. I’m going to do this for the long run,’” he says. “

But the challenge proved to be his sweet spot as a founder. “The more I explored it, the more it turned from impossible to doable — but hard. And ‘doable but hard’ is my favorite place to be,” he says.

In the beginning, spend all your time doing the thing you're the least capable of doing — and the least capable of proving to the world that you can do.

— Immad Akhund, CEO and co-founder of Mercury

13. Know if your business is a follower or pioneer

Alyssa Henry, former CEO of Square and board member for Intel, Confluent, and Samsara, argues that every company leans toward one of two core identities: pioneer or fast follower. A startup will likely possess traits of both, but Henry says founders must be honest about which identity they’re leading with, because it shapes everything from product-building priorities, to brand voice, to hiring.

“Microsoft is an incredible fast follower, very good at seeing something happening out in the landscape and doing it better, cheaper, and faster,” she says. “Competition has to seep from a fast follower because it’s all you’re defined by. And frankly, in the absence of competition, the company struggles.” Amazon, when it was first founded, was a quintessential example of a pioneer. “Amazon struggled at being a fast follower because its operating mechanisms weren’t built to follow. They were built to pioneer something.”

The follower versus pioneer distinction is especially important, Henry says, when it comes to your product roadmap. When you’re not the first in the space, you need to push yourself much further to differentiate your product and exceed expectations.

“If you’re new, and if it’s viable at all, the reason it’s viable is because it’s remarkable,” Henry says. “But if you’re a follower going into an existing space, you can’t say ‘Oh, we launched this and it does all the minimal things somebody needs.’ The marketplace is going to say ‘So what? If it’s not 10x better, I don’t care.’”

14. “Meme-ify” your product idea to gain internal momentum

When the idea for Figma Slides was still in its infancy, founding PM Mihika Kapoor made an offhand decision to give the project a silly name. “It may feel random, but a big part of what made Figma Slides go internally viral was the fact that we called it ‘Flides,’” she says. “It’s a totally absurd name that you could not go to market with, and yet, this was the thing that made people feel the most irrationally attached to the project.”

What started as a tongue-in-cheek nickname quickly snowballed, with colleagues across the org joining in on the fun: the animation sync became the “flanimation” sync, and the layout workstream turned into the “flayout” workstream.

As Kapoor accidentally discovered, a little playfulness that makes people feel excited and included — going viral, essentially — helps to spread awareness internally for a project. “It was ultimately this meme that people were able to take and run with,” she says. “That’s because being kooky humanizes your idea. It makes it easy for someone to bring it up in a Zoom chat, or with a Slack emoji. To this day, people are pitching me on why Flides is a better name for this project.”

For those looking to recreate Kapoor’s success and meme-ify their own project, she offers a few practical tips.

- Come up with a code name. “Brand can be built in so many different ways… Think about code names for your project. Think about iconography — what visuals do you want to be synonymous with your project? Use that to inspire you.”

- Use the “double take test.” “If someone is getting an overview of all the initiatives going on at the company, will a new hire ask to learn more about your project? If you’re telling your mom about your day at work, is she asking to learn more about what you’re working on?”

- Make a custom Slack emoji. “It will cause this interesting trickle-down effect. It starts with you reacting to every message with it. Pretty soon, your team will start using it, and then your company will. It’s a programmatic version of taking a project and getting it in front of the company asynchronously,” she says.

If you haven’t already made a Slack emoji for the project you’re working on, I recommend doing it right now.

— Mihika Kapoor, former Product Lead at Figma

15. Tell your users how they should experience your product

Back when Karri Saarinen was a product designer at Airbnb, he hated the project management tools he had to use. He found them cumbersome and slow. So he built Linear with a very specific user in mind: himself.

He and the early Linear team took their time to design an MVP that would clear their own high bars. “We wanted the first product to get to the state where we could use it every day for our own basic workflows,” says Saarinen. “We were the first ideal customer. So we just had to build something nice for ourselves that actually worked.”

Saarinen was extremely opinionated about how this software should look and feel, taking a page from the Apple school of software design, which creates a universal experience for every Mac or iPhone user. “I don’t think you can build the optimal tool for anything if it’s very flexible or endlessly customizable. So from the beginning, we had a strong opinion of what a good workflow looks like and we provided standards and defaults for how to operate,” he says.

16. Give engineers “wolf time”

Michael Lopp, who has spent his career building products at Palantir, Slack and Apple, believes that engineers need time carved out for open-ended, curiosity-driven exploration. He advises a specific 71/29 split: “71% of that time is very clear. Build things that you need to, get them done and get positive feedback,” he says. “The other 29% is time to do whatever the heck is inspiring you based on the 71% stuff.” This creative window (he calls it “wolf time”) is an invitation to wander, experiment and follow threads of inspiration wherever they lead.

What happens during this time can’t be explained to a manager, and Lopp says that’s exactly the point. “It’s time for things to be created and spin out of that little poetry jam, and you can't let management and product folks into that world. They’ll know when something’s happened there, and it always does.”

From his own experience, Lopp cautions leaders not to formalize wolf time. Instead, he recommends encouraging eng teams to treat it as a space of freedom and autonomy, and make it clear that exploration is essential to long-term innovation.

17. When making AI products, move fast by separating product performance and UX

The biggest lesson Carta’s Director of Machine Learning, Jayant Tikmani, learned from building the company’s internal AI agents was the power of separating the model’s behavior — its instructions, context and reasoning — from the front end.

“Unlike traditional software, where performance is largely driven by deterministic logic, AI product performance also depends on model behavior, which is controlled through model choice, instructions and context design,” Tikmani says. “To enable fast iteration, decoupling this layer from the UX and workflow integration is important.”

This decoupling gave Carta’s engineering, product, and AI teams the freedom to evolve the agent’s output without needing to constantly rebuild the front or backend systems, enabling them to move quickly. Model behavior was separately tested in rough setups by domain experts, while UX was rapidly iterated upon for the best user experience. Eventually the two came together but in the prototyping phase, this split was extremely valuable for developing a product for fast impact.

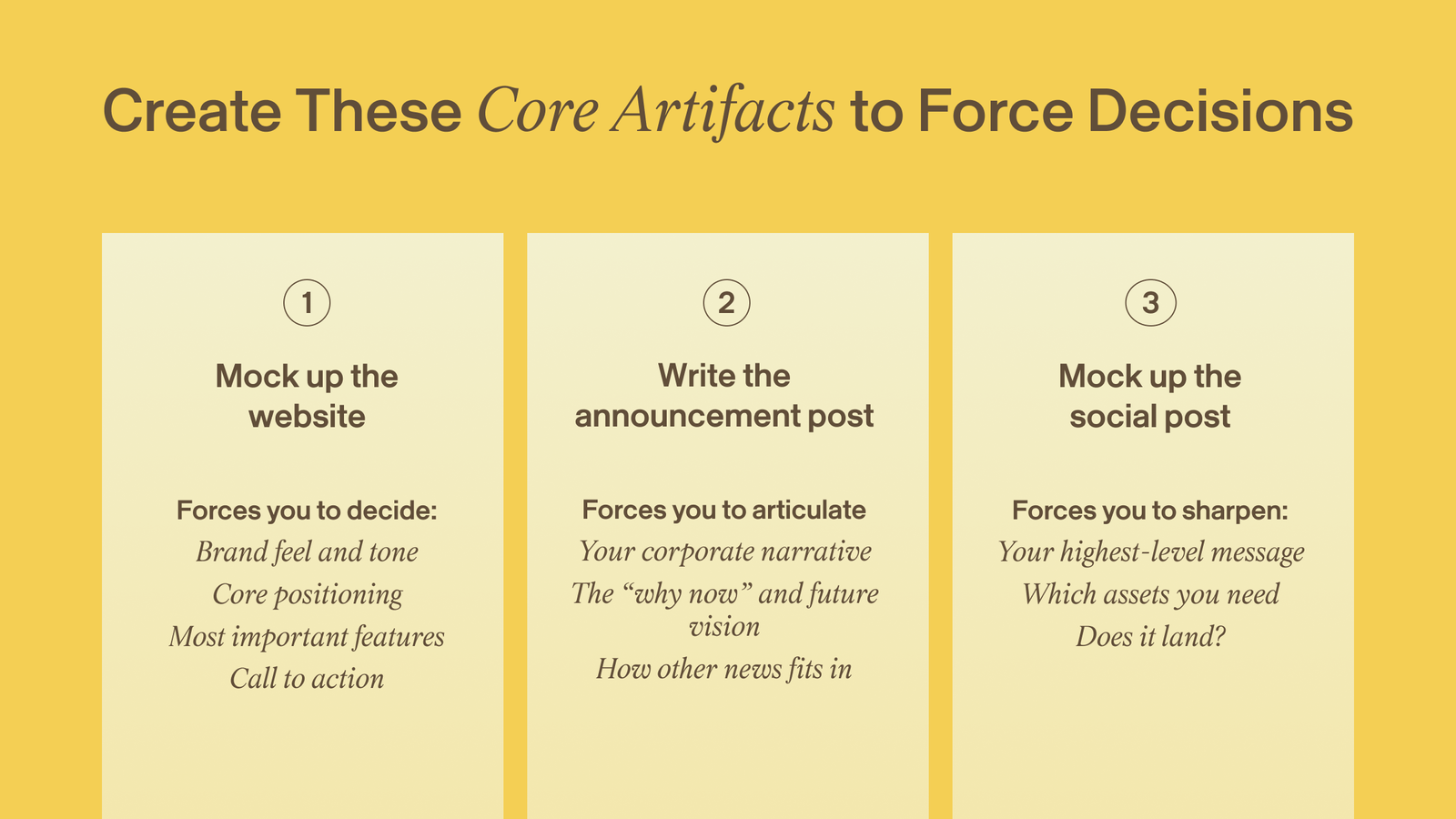

18. You only need these three artifacts to launch your product

Coming out of stealth feels like the biggest moment in your startup’s history. The pressure around it can lead to decision paralysis.

Claire Butler understands this fear, having joined Figma back when the team was still building in stealth, and helped scale the marketing function from launch all the way up to IPO.

Her launch playbook brings a sense of stoicism to the process. Her first piece of advice in regards to timing is to just set a date, almost at random — and work backwards from there. You can always move it. Setting a date charges you to actually draft up all the materials you’ll need on launch day and hone your marketing fundamentals. “The worst thing you can do is get stuck in a massive brainstorming file where you’re making tables about features and benefits,” she says. “Even well before you’re ready, creating launch materials will force you to sharpen your positioning.”

Mock up these three artifacts:

- The website. “Once you have your positioning statement, do your website first,” says Butler. It forces you to decide fundamentals like brand feel and tone, core positioning, most important features and a call to action.

- The announcement post. This is the launch note that comes directly from the founder. “Whether you ever post it or not, I’d encourage the founder to write an announcement post,” says Butler. “Do it yourself. This is something that should come straight from the founder — and explain your vision, why you built this thing and where you’re headed long-term.”

- The social post. This comes from your company handle (pre-launch is a good time to set that up, even if you don’t plan to post yet). “This one’s quicker, because you’re distilling everything from the website and the founder’s announcement into its simplest form,” she says.

19. Make sure your product passes the “screenshot test”

Figma CPO Yuhki Yamashita has a simple test to determine if a product is fit for launch: Can someone understand its value in a single screenshot?

At Figma, visuals are king, so Yamashita likes to distill a product’s story down into a clear and compelling image for launch communications. “What’s the one screenshot that’s completely self-explanatory?” he asks. “You need to show something people want. That’s a design problem. That’s a storytelling problem. That distillation is really important.”

He points out that it’s easy to lose sight of how a user will first encounter the product if you’ve been knee-deep in its development. If you find yourself having to add context to a screenshot, that’s a flag that the product has gotten too complicated. “If you’ve been involved in the evolution of the product, you can empathize with how you got there. But users don't see that evolution — they’re coming fresh at a screenshot with no context. If you have to explain what's going on, that's an indication that you haven’t made the value proposition simple enough,” he says.

20. Your first two Customer Success systems should be support tickets and onboarding

In the early days, your first Customer Success hires will naturally be focused on handling whatever customer issue pops up next. But Atlassian and LinkedIn CS alum Stephanie Berner urges founders to not let that become your operating model. If you want to scale, you must establish foundational systems that bring consistency to how you support and onboard customers. Berner says there are two key areas that are most important to focus on.

- Support tickets. “You need a way for customers to reach out to you,” says Berner. “Whether that’s through a Slack channel or an actual support system, you need a systematic way of collecting that customer feedback that's not just an email.” Beyond communication, she notes that as volume increases, ticket systems become a diagnostic tool — the only reliable way to categorize issues and understand what’s really happening with your product.

- Onboarding. “A big mistake I see companies make is that they don’t codify the multi-step process of getting a customer onboarded,” says Berner. “If you don't have that early mindset of creating a checklist, your business can end up scaling without you having a consistent way of onboarding customers, and that means there’s a weak understanding of what it takes to get a customer to value.”

While support systems can take many forms, Berner recommends keeping the first version of an onboarding manual incredibly simple — think a shared Google Sheet outlining the 10-step process. “The details of that implementation are different depending on the product, but onboarding manuals should always include a kickoff call and a requirements gathering conversation,” says Berner. “Then it's planning out each of those steps. Ask yourself: ‘What data do we need to gather, and who's going to deliver those files or build that API? Who's on point to build the communications that will go out to our users when we roll out this product?’”

21. Treat design partnerships like real contracts

Some founders think of design partners as casual collaborators. But Logan Randolph, GTM lead at Sierra, says that in his experience, open-ended, casual partnerships rarely work. Instead, both sides need to be invested. The quickest way to get there? Payments and time limits.

For Sierra, this approach helped filter out companies that were merely curious about AI.

Everyone’s excited to experiment with AI. So the financial commitment had to be significant enough that people really needed to think about it, get approval from their boss and go through the procurement process.

— Logan Randolph, GTM lead at Sierra

For founders figuring out their own pricing, he suggests a simple benchmark: “10–20% of your total contract value feels right. Anything less than that and it’s not that real of a commitment.”

When it comes to time limits, set clear, firm deadlines. “Whatever you do, don’t allow the ‘try this and give us feedback when you are ready’ approach,” Randolph says. Without constraints, teams deprioritize the work and momentum evaporates. Instead, set tight guardrails: “If you say, ‘We’re going to work together for three months and then the partnership period is over,’ they’ll show up the next week ready to get to work.”

While it’s going to be different for everyone, Randolph offers a useful range. “Under two months is probably too short and over six months is probably too long,” he says. The window of time should be long enough to build together and see results, but short enough to keep both sides engaged and accountable from day one. As Randolph notes, Sierra can now launch agents in a week, “but when everything was new, it took a bit longer,” making these boundaries even more critical in the early stages.

22. Don’t aim for 100% automation when making an AI product

As AI integration continues at a rapid clip at companies of all sizes and industries, clarity, nuance and practical implementation frameworks matter (which is exactly why we started Applied Intelligence, our AI focused series). Brex CTO James Reggio says being strategic, by identifying where AI is going to be most impactful in your workflow is the key, even if it means automating only a fraction of what the processes and tasks you technically could.

“When you set the goal at 100% automation as opposed to 40% automation, you end up making investments that are oftentimes going to yield zero value because they have a binary outcome.”

By resisting the all-or-nothing framing and starting with partial but targeted automation, Brex has seen value compound quickly. Brex’s fraud agent is a great example. Building a system that could replace analysts entirely, with 100% confidence in every recommendation, would have required enormous engineering work, with uncertain payoff. Instead, the team automated only the cases where the model demonstrated high confidence, and routed everything else to human analysts, who were supported with AI-generated findings. This hybrid approach delivered immediate operational efficiency while still improving analyst judgment and throughput.

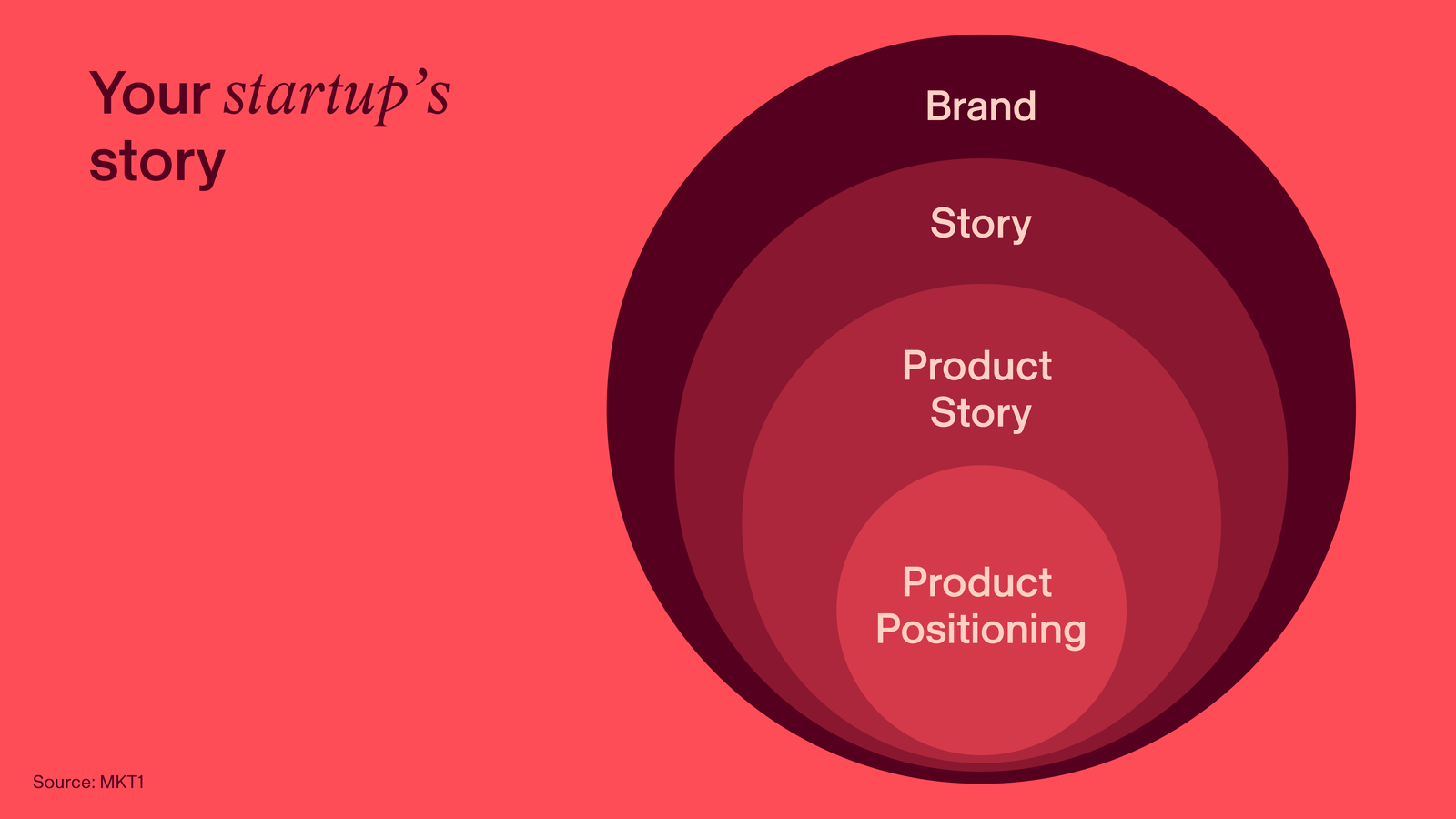

23. Your marketing story is bigger than your product story

Some of the first marketing every founder does is their pitch deck. So it’s understandable to want to squeeze as much juice out of that hard work as possible, and repurpose some of that language in customer-facing materials.

But don’t ship your pitch deck to your website, says Emily Kramer, former marketing leader at Carta and Asana and now, a B2B startup marketing advisor and author of the MKT1 newsletter.

“Investors and customers care about different things. A fundraising pitch should cover what’s important to investors: your big vision, your team’s unique ability to solve the problem and the market potential. But effective marketing, especially in the early days, needs to speak to a much narrower audience and a much more immediate pain,” she says. “Your pitch deck might have helped you raise a seed round, but it won’t help you close your first 10 customers — unless you know how to translate it.”

To find the language you’ll use to talk to customers, think bigger than just your product. “In addition to writing clear positioning, choose three to four narratives you want to focus on that speak to your audience. These can be related to market trends, what your customers have in common, your founding story or a unique insight or contrarian view you have,” she says.

She calls these narratives perceptions. “Your perceptions may be adapted from slides in your pitch deck, like your ‘why now’ and ‘vision’ slides, but they’re geared toward the perspective of your customers. Focus on movements and trends your customers actually care about, rather than what excites investors.”

24. Don’t write off founder-led marketing (even if it doesn’t scale)

Adam Guild spent much of his first year building Owner hustling with cold outbound, literally going door to door to restaurants around LA. He’d found a handful of early customers this way, but he eventually reached a breaking point. “I didn’t want to scale a business through outbound because it was so brutally hard. I basically had to spam people to get them to take my meeting. So I wanted to develop a model where they would instead come to me,” he says.

He knew he needed to drum up inbound business. Content seemed like a good place to start, but he had no credentials in the restaurant industry. So he started to pitch trade publications with article ideas, leaning on his experience having done outbound sales. The editor of Modern Restaurant Magazine gave him a chance — and his guest post wound up becoming the magazine’s top piece of the year.

He says the writing process doubled as a crash course in the industry. “The work I was doing to research these articles improved my ability to communicate with the restaurant community, and gave me a much deeper understanding of the broader landscape,” he says.

The founder-led marketing strategy paid off: Several strong leads came directly from Guild’s article, allowing him to successfully bootstrap the company to six figures in ARR.

25. When selling to enterprise, think emotion, not logic

Technical founders often assume buyers make decisions the same way they do: rationally, based on specs and performance. Reducto founder Adit Abraham once thought this too, until he discovered that enterprise sales runs on storytelling, trust and executive buy-in far more than objective evaluation.

“You’re probably someone who approaches your own buying decisions from a very rational perspective,” Abraham says. “You choose whatever you think will perform the best. But with enterprise sales, it’s much more relationship-driven in a way that surprised me as someone who didn’t come from a sales background.”

Instead of showcasing the product, running through features and metrics and assuming that’s what will convince the stakeholder at a large organization, Abraham advises founders to offer a solution to the specific pain that’s hampering productivity for that buyer and their company or industry.

“The more I’ve thought about selling from that lens, the easier everything else becomes.”

In founder-led sales especially, make your audience feel your excitement about, and belief in, the product.

Your energy as a founder is contagious. When people see how much you care about the product, they start to care about it more, too.

— Adit Abraham, Reducto founder

26. Run a memorability test to pick the right name

It’s tempting to rush into lists of clever words or domain checks when naming your startup. But Arielle Jackson, Head of Brand and Product Marketing at First Round, who’s guided many a founder through the name-choosing process, says it should take time (at least a month).

“While picking a name is more art than science, having a process results in a name that’s more intentional, and usually better,” she says. Once you have a shortlist of potential names you like, one of the tactics she’s seen work is to play a memory game.

“I like to run a simple test: talk with several people about the three names you’re considering,” she says. “The next day, go back and ask them to recall the names. See which of the three they can remember.”

As for what’s most likely to stick, there are a few factors solid brand names often have in common.

- Concreteness: when a name evokes an image, like Apple or Red Bull.

- Functional relevance: this could be something very literal, like HotelTonight, or a word or phrase that evokes something the product is known for, like Swiffer, which captures the sound of sweeping.

- Wordplay: think phrases that are alliterative or just fun to say, like Firefox, Coca-Cola, or 7-Eleven, or a deliberate, playful misspelling, like Lyft.

27. Find personality–message fit to make your message resonate

Maven co-founder and executive coach Wes Kao urges founders to lead with their natural communication style instead of trying to emulate someone else’s. “We've all seen somebody pretending to be Steve Jobs, or trying to be Mark Benioff, and it’s not landing,” she says.

“I don't think that we, as founders or leaders, can change 180-degrees, even if we want to.”

She calls this process finding personality-message fit — the other PMF. It allows you to more effortlessly connect with your audience and make your message land with them. The simplest way to do this is to amplify and refine the traits that come naturally to you, and compensate for the ones that don’t.

Personality-message fit is about what makes you you, instead of trying to copy someone else and having those tactics fall flat.

— Wes Kao, Maven founder and executive coach

Kao encourages founders to start by identifying their own default communication tendencies by taking an inventory of sorts. Do you lean toward being more exuberant or reserved when pitching? Do you tend to pull from anecdotes or data? The other side of this is being strategic and accommodating these traits. If you’re naturally less emotive, Kao’s tip is to make sure you use words that express how you’re feeling — for instance saying, rather than showing, “I’m so excited about this.”

28. Seek rejection to build founder resilience

“The founder journey isn't just about managing long hours and a heavy workload. It's about navigating profound identity shifts, handling persistent loneliness and learning to lead through failure.”

Psychologist and co-founder of Coa, the gym for mental health, Dr. Emily Anhalt advises early-stage founders to build “emotional calluses” by asking each day for something they’re almost certain they won’t get. The point is to get used to hearing “no” and build the comfort with rejection and ambiguity needed to be a founder. Resilience comes from learning to operate even when fear or anxiety is present, rather than waiting for those feelings to disappear.

Think of it as creating shock absorbers for your emotional vehicle. They don't eliminate the bumps in the road, but they make them more manageable.

— Emily Anhalt, Coa co-founder and psychologist

Anhalt has observed that founders often prepare extensively on the tactical front but rarely train for the emotional realities that come with the job.

“Most aspiring founders spend countless hours preparing for the logistical challenges of starting a company but very little time on the emotional resilience required to run that company,” she says. “They’re perfecting their pitch deck, not unpacking why they want to start the company in the first place. They’re building financial models instead of community. They expect stress, certainly, but they frame it as something to push through until they ‘make it.’ This mindset sets them up for a harsh wake-up call.”

29. When making a tough call, ask yourself this vital question

In the 14 years since David Cramer founded Sentry, he’s regularly had to make tough calls in order to steer the company’s trajectory. When faced with such moments, there’s one question he asks himself to be pointed back in the direction of his north star, and he recommends it to other founders.

You have to ask yourself: does that align with my view of the world? Specifically, you need to ask if something aligns with your view of the world in the future, versus in the past.

— David Cramer, Sentry co-founder

One example of this was early on, when Uber, at the time one of their largest customers, pushed for a paid, on-premises version of the product. Sentry initially agreed and provided the service, but Cramer knew on-prem was a detour from the correct path for Sentry. Even though it would have been a lucrative contract to renew, he declined. “I didn’t want to sell on-prem software,” he says. “I didn’t want to be in that business.”

Another example was when Best Buy asked Sentry to complete a detailed request for comment, a pre-contract proposal outlining how Sentry would implement and integrate the product. Even knowing he’d lose a potential customer, Cramer again said no. “It did not seem like the best use of my time. I’d rather get 10 new customers instead of Best Buy.” It turned out to be the right call. Best Buy did eventually become a Sentry customer, just not right then.

“Saying 'no' to things you don't believe in is really important,” he says. “You have to steer those decisions, and have conviction they align with your vision.”

30. Make sure your AI product’s eval process includes its target user

While building Figma Make, the AI tool that allows users to create and edit designs faster, Head of Product, AI David Kossnick made a decision: the target audience would be in the room for eval.

The AI team invited Figma designers to provide feedback on early prototypes, knowing their opinions on functionality, features, and aesthetics would hold the most weight. There were several rounds of feedback, with designers, as well as engineers and PMs, giving their input.

As Kossnick plainly put it, “garbage in, garbage out.”

The first round was conducted via Slack, where they were asked to include their prompt, a link to what they created, and the design and functionality scores (rated 1–4). “In one day, we got hundreds of example prompts,” Kossnick says. “We quickly learned there isn’t one quality bar.”

For the next round, the team built a sprawling FigJam board and had users add their prompt, result, and scores directly to it. The endless canvas created a shared space that encouraged collaboration and creative thinking.

“We got 1,000 examples of real things people wanted to build, use cases where the product fell over, places it did great and unexpected areas for each of these,” says Kossnick. “This shaped our features and designs. Once we felt like there was a path on quality, we could invest a ton more in the whole product experience, its form factor, longtail features and workflows.”

When the end user helps shape the evaluation criteria from the start, you dramatically reduce the risk of shipping something that works in theory but falls flat in practice. It also speeds up alignment across the team: engineers understand what great looks like to designers, designers see what the AI can unlock, and PMs can anchor decisions in user value. All of this Kossnick and his team learned first-hand.

“It was probably the most helpful day of the entire project."