“Every article will serve up tactics that you can use today to change your company and your career.”

This was one of the three promises we made when we first launched The Review back in 2013. It was a pledge to stay in the tactical weeds, to find the sweet spot of both enduring, evergreen advice and the “I’ve gotta try that out today” kind of read. (Or as one of our readers recently put it, “oddly specific, yet perfectly helpful.”)

There’s power in the specifics, in the counsel that shares the how-to, not just the what-you-should-do. In the story of the CEO who analyzed every 15-minute increment of his calendar for the past two years. In the targeted question set one founder uses to compel others to give her better feedback. In the detailed framework for hiring a VPE. In the advice on how to find a signature topic for your first public speaking keynote. In the case study on how one marketing team secured +100 podcast interviews for their founders in six months.

If these specific examples sound somewhat familiar, then you’ve been reading along this year, as they were all drawn from articles we’ve penned in the past 365 days. And they’re still top of mind for us right now for a particular reason.

Since 2013, we’ve committed ourselves to an annual ritual, one that serves as an opportunity to both take stock and remind ourselves of that early promise to stay tactical. Each time we turn the page to the new year, we comb through every article we published over the last one to concentrate the standout tactics into one actionable guide of advice. (To see how this project has evolved over time, check out our installments from 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020.)

As we set about to pluck out the tactics, quotes and frameworks from the previous year that we haven’t stopped thinking about, a few themes invariably start to emerge. It wouldn’t be a 2021 retrospective without a nod to the “Great Resignation” — folks up and down the org chart are reconsidering their career goals and resolving to pour more into their own personal development. It’s a topic we tackled head-on, whether by tapping our First Round community to gather their tips on how ICs can take charge of their own careers, getting therapist Minaa B.’s take on making self-care tactical, or crowd-sourcing ideas for upping your management game.

That very same itch pushed others to try on the founder’s hat for the very first time, which is why we kept a keen focus on lessons for first-time founders this past year — particularly on that messy pre-product/market fit phase, where founders are staring down a lump of clay on the pottery wheel, hoping to sculpt it into an enduring work of art. Given that advice for founders tends to come from those who are many years removed from those early chaotic days, we relished the opportunity to speak to folks who are still early in their founder journey, like Ryan Glasgow of Sprig, Rick Chen of Persona, and Tara Viswanathan of Rupa Health.

As always, we hope you find relevance, resonance and few ideas to try out for yourself in the following roundup of the 30 best pieces of advice from our articles last year. Here’s to all the micro-actions and tactics that will transform companies and careers in 2022 — and to the startup leaders who will generously share them.

1. Managers — pay attention to these little daily habits to unlock your team’s superpowers.

When it comes to upping your management game, most advice tends to focus on the big tentpole moments — hiring, delivering feedback and checking in regularly. Of course, holding regular 1:1 meetings and honest performance reviews are critical items on your manager checklist to get right, but there are plenty of smaller habits that are just as important to pay attention to. So we sent out a call to startup leaders in the First Round community to crowdsource a list of the small things that make great managers stand out. Here are a few of the highlights:

- “Great managers demonstrate self-awareness and empathy by sharing their working style preferences and development areas. I've always appreciated when managers provide an onboarding guide to who they are as a person and a manager. This should include their work styles, expectations of their directs, values and motivations, areas of feedback they are working on and decision-making preferences,” says Dennis Yu, VP of Program Management at Chime.

- “I trust you, make the call” might be the six most powerful words you can hear from a supervisor,” says Sean Twersky, VP of Operations at Sprig.

- “Bang the drum — literally. A friend of mine loves using props to get her team fired up, like a tambourine she shakes when she’s excited about what someone says. Great managers do small things to help their teams have fun and take the work seriously while not taking themselves too seriously,” says Sunita Mohanty, New Product Experimentation at Meta.

Each individual person’s strengths are superpowers that lead to an all-star team. Find moments to recognize specific ways that each person’s superpower shines and encourage team practices around sharing gratitude for each other.

2. Ditch your to-do list and use your calendar instead.

“As a startup CEO, being a master at time management should be one of your core competencies. You’re going to have a lot of balls in the air and you need to make sure you don’t drop them — or at the very least, ensure that they don’t drop silently,” says Levels’ Sam Corcos. As a repeat founder, he’s tinkered with a few time management techniques over the years, but the biggest win came from ditching his to-do list altogether and leveraging his calendar instead.

The problem with to-do lists is they lead to unrealistic optimism about how much you can accomplish because items on a to-do list are untethered from the constraint of reality: time.

Tactically, if Corcos has a task that needs to be completed, he now blocks off time for it on his calendar. “I used to have the habit of overcommitting myself, which became a major source of anxiety in my life because I was dropping balls left and right, and it led me to disappoint a lot of people when deadlines would slip,” he says. “When people ask me now, ‘Can you have this done by Friday?’ I can easily look at my calendar and respond, ‘I have exactly two hours open this week, so if it’s going to take more than two hours, we’ll have to change my priorities or I won’t get it done until next week.’ Having this level of clarity on my time has been a huge win,” he says.

3. Build MVTs, not MVPs.

The typical approach to getting a startup off the ground is to conduct some customer research, throw an MVP out there as fast as possible, and cross your fingers. After being early at three startups that achieved over $1M in run-rate in their first six months of going live, Gagan Biyani has landed on an alternative approach. Here’s a condensed glimpse inside his MVT framework which resonated with so many founders last year. (Be sure to read his article in full to soak up all the tactical nuances.)

The difference between MVTs and MVPs: “An MVP is a basic early version of a product that looks and feels like a simplified version of the eventual vision. An MVT, on the other hand, does not attempt to look like the eventual product. It’s rather a specific test of an assumption that must be true for the business to succeed,” he says.

If you build an MVP, you start to think about the 20 features you might build to make people happy in a market, which takes your eye off the one specific insight that the customer actually cares about. Purity breeds success.

Instead of building a full-on MVP, Biyani proposes running through the MVT framework, repeating these steps until you’ve learned enough to de-risk your biggest hypotheses.

- Find your value proposition. Determine the promise of your idea. Why would users want it? What are you promising them?

- List your risky assumptions. List the primary risks: why might this not work? What breaks your system?

- Test the atomic unit. Determine whether your idea actually works. Focus only on the “atomic unit” of what you plan to sell. For Google, the atomic unit is a search query. For Amazon, it’s ordering a book online. For Coinbase, it’s an easier way to buy and sell crypto.

“When starting Maven, instead of trying to test everything with an MVP, I picked just one risk to start: Will consumers be satisfied with buying a cohort-based course for a significantly higher price point than video-based courses?” says Biyani. “As a test, I decided to run just one course. It was a hyper-narrow test that achieved the exact result I was looking for: The course had a 9/10 rating from its students and made over $150,000 in revenue in its first cohort.”

4. Assemble these four lists to find your most fulfilling career path.

Perhaps there’s no interview question quite so dreaded as, “Where do you see yourself in five years?” Career planning is expected to be top-of-mind for folks, particularly when approaching a new job opportunity. But in reality, many often take a much more haphazard approach to plotting the points along their career roadmap.

So we turned to folks in the First Round community for the specific pieces of advice they’ve leaned on to take the driver’s seat in their own career planning. Molly Graham (of “give away your Legos” fame here on The Review) tactically recommends folks start with these four lists:

- Things I love doing

- Things I am exceptional at

- Things I hate doing

- Things I’m bad at

“The best version of your career is finding jobs that are in the Venn diagram between what you love doing and what you’re exceptional at. This may sound obvious, but oftentimes as you get more senior, the Venn diagram is often ‘things I’m exceptional at’ overlapping with ‘things I hate doing.’ You have to know yourself well enough to turn those jobs down, even when someone offers you the super sexy role full of things you hate doing. It’s a role that will bring out the worst in you,” says Graham.

This isn’t a one-time list you make only in the early innings of your career. Every work experience you have — every project, every role — can add more data to the lists. Use these questions as your guide:

- What were my favorite things that I did this last quarter?

- What moments or weeks did I feel at my best?

- When did I feel like I could keep doing the same set of things over and over again and be happy?

- When did I feel drained or depleted?

- When did I feel bored?

- At what moments did I feel like my worst self?

5. Remind yourself that self-care is deeper work.

Self-care has taken center stage over the past couple of years, magnified all the more by the wave of isolation, stress and burnout caused by the pandemic. In one of our favorite pieces of the year, therapist Jessmina Archbold (publicly known as Minaa B.) challenged us to go deeper than the well-worn suggestions to indulge in a bubble bath or yoga session.

“Self-care is seen as what you can buy yourself, not how you can work on yourself. In my view, self-care is deeper work — there’s a difference between engaging in self-soothing relief from a discomforting emotion, versus tackling the hard work to take care of yourself on a deeper level,” she says.

It’s also about matching the medicine to the moment. “If your body is feeling tight or you’re stressed, working out is a great option. But if you're feeling depleted more on a social level, doing a workout video by yourself isn't going to help,” she says.

Archbold offers a three-tiered self-care inventory system to break down the available options, ranging from immediately accessible to bigger investments of your finances, time, and energy. “If I feel dysregulated, I can do some deep breathing in the moment. But if I notice a pattern of often feeling this way, I could take on the Tier 2 work of booking a session with a therapist, which requires planning and saving that money. When I go to therapy, my therapist might give me homework — now I’m in Tier 3, where I need to carve out time and space within my day to sit with these practices that I'm learning," she says.

This approach also helps foster accountability. “Maybe you notice that you’ve really only been taking on Tier 1 work of breathing exercises or drawing a warm bath lately, and there’s room to step it up and invest more of your energy into yourself,” she says. “You can take on some Tier 3 work, like reading a book on boundaries before bed, or watching a TED talk on dealing with trauma for an hour.”

Sometimes self-care might look like taking a bath. And sometimes self-care might look like speaking up, erecting boundaries, being assertive and holding yourself accountable.

6. Focus on the functional message to find language/market fit.

After more than a decade of running B2B growth teams at PayPal, investing at 500 Startups, and now helping early-stage companies tackle growth at Startup Core Strengths, Matt Lerner has seen firsthand how changes in a handful of words can yield jaw-dropping differences in conversion. On The Review last year, he shared his 4-step process for finding language/market fit, which is a bookmark-worthy read for any founder or marketer.

Here’s a snippet of Lerner’s case for why finding the exact right language is so crucial: “What seems like a simple purchase decision sits within a larger context in the customers' lives,” he says. “If you could stop people in the middle of their day and snapshot-read their minds, you would not find a list of product features or marketing platitudes. You would see anxieties, fears, doubts, hopes, dreams and struggles. Therefore the best way to get past the attention filter is to talk about the stuff that is in their heads — specific goals, struggles and doubts.”

This focus forgoes the flashy. “Your marketers and your agency will call these messages boring, derivative and functional. Because every marketer wants to write the next ‘Just Do It’ or ‘Think Different.’ (And who can blame them?)” says Lerner. “But here’s the problem: Nike and Apple already built ubiquitous awareness and comprehension, so their ads can be ephemeral and allusive. They earned that right over decades. Your innovative little startup did not (yet). So you need to start with clear functional messaging until people understand what you can help them achieve.”

Here’s Lerner’s simple test for if you’ve reached it: “If your headline completes the sentence ‘Our product is…’You’re not using their words. If your headline completes the sentence ‘Now you can ______’ or ‘I wish I could _____’ or ‘Someday I hope to _____’ then your language might resonate.”

7. Write this letter to bring warmth back to your onboarding flow.

Joining a new job remotely can add an extra helping to the plate of new-job jitters. To ease the transition, Segment design leader Hareem Mannan added a new touchpoint in her team’s onboarding flow. “We’d realized that we had been doing a good job operationally of getting folks onboarding to the product of what Segment is and who are the people at the company. But the warmth aspect was missing once we shifted to remote,” she says.

To close the warmth gap, she asked her team to start putting pen to paper. “We started a series called ‘Dear New Designer,’ where every designer on our team writes a letter to the new designer joining, sharing what they wish they did or wish they knew when they were onboarding,” says Mannan. “It’s a complete hit with every single person who’s joined because people are able to take that onboarding doc that’s chock full of ideas and then decide how they want to approach onboarding based on their role, who they are, and how they like to learn.”

8. Avoid the early startup employee headaches that come from “I’ll fix this later.”

Even in the best of times, startups are challenging — they’re specifically designed for growth, which comes with a unique set of stumbling blocks, risks and demands. So earlier this year we tapped startup leaders and operators for their favorite unexpected tip for someone joining a startup for the first time.

One common theme in the advice we got back? Move quickly — but thoughtfully. “Set yourself up to scale. I've fallen into the trap of hacking something together thinking, ‘If this works I'll just fix the setup later,’ and then spending months importing a CSV into a Google spreadsheet, manually reformatting it line-by-line, redownloading it as a CSV, etc. Once you know you're going to invest in something, spend a little extra time upfront to put the right tools, processes, and documentation in place. You'll save yourself a lot of headaches down the line,” says Liz Fosslien, Head of Content at Humu.

To combat this “I’ll fix this later” mindset, John Zanzarella, VP of Sales for PerformLine, relies on a simple rule:

Build processes and systems for anything that you end up doing twice.

Even if there are processes in place — if you spot an opportunity to make critical tweaks, by all means, speak up. “Most policies, procedures or methods are not as fixed as you think. That process you don't like? Someone probably threw it together in 15 minutes and then moved on to the next urgent thing. If you don't like it, offer a way to improve it,” says Nick Hurlburt, Director of Engineering at Tech Matters.

9. Try something with no teeth for a quarter.

Last year, the First Round team welcomed Meka Asonye into the fold as our newest partner. In the transition from operator to full-time investor, he’s since forged partnerships with incredible companies like Composer. When partnering with technical or product-driven founders thinking through go-to-market motions for the first time, Asonye has a deep well of fresh-from-the-trenches experiences to draw on — from cutting his teeth at Stripe as it grew from 250 to 2000 people and scaled its sales org, to owning the customer lifecycle as the VP of Sales and Services at Mixpanel.

Asonye shared tons of GTM wisdom on The Review last year, but we’ll highlight one nugget here: Get more creative when it comes time to think about comp. “There’s a traditional playbook in terms of how you compensate sales folks and motivate them. At Stripe, we did things differently.” Here’s what he means:

- Team above self. “We had team quotas for individual lanes and that's not something that you typically see. And for our first year, we had around a 10-person sales team with no variable compensation,” he says.

- Train for behaviors. “You get the behavior that your comp plan designs for. In the early days, I prefer to keep comp plans simple with two metrics, max,” he says. “I also love plans that have a component focused on the entire customer lifecycle. For example, comping teams on bookings and retention can be a powerful way to ensure teams pursue the right users who will be longtime customers.”

- Test the waters. “A common pitfall is failing to figure out if you're actually ready to put somebody on a comp plan. You need to have reasonable predictability to be able to say, ‘I think you should be able to achieve X.’ It's not a great outcome if they achieve 100X, and it's also not a great outcome if they achieve 1% of X,” he says. “At Stripe, we oftentimes would try something with no teeth for a quarter. We’d say something like ‘Your quota is going to be X and we expect that you can get to X through Y leads.’ It wouldn’t be a goal tied to comp just yet, but we’d track the metrics, report on it, and see what it would have paid out if it were in place. If it worked out, we’d officially roll it out the next quarter. That hedges the risks, frees up room for people to experiment, and allows you to double check to make sure you didn’t unintentionally create perverse incentives.”

10. Lean on these questions to turn yourself into a feedback magnet.

When it comes to feedback, we often focus on mustering up the courage to (tactfully) deliver it to others. “We rarely focus on how to attract useful feedback about ourselves, and we often unintentionally repel the rare feedback that does come our way by getting defensive or shutting down,” says Ascend's Shivani Berry. “But the best leaders are feedback magnets.”

In her two-part playbook for becoming one, Berry focuses on getting better at both receiving and encouraging feedback — we’ll focus on the former here. “When most of us hear, ‘Can I give you some feedback?’ an instinctual ‘Uh-oh!’ feeling kicks in. When our colleagues say ‘This one part of the design isn’t solving the customer problem in scope,’ we hear it as, ‘I’m a terrible designer,’” she says.

“Instead of giving into these fears, you’ll learn more by leaning into your inquisitive side and asking questions. Asking good questions breaks through fear’s distortion field. It enables you to process the message in a more accurate and insightful way.”

You can’t trust your initial reaction to feedback. Defensive responses are driven by common fears about our own competence, and fear is a powerful distorter of the messages we hear.

Here are the targeted questions she leans on:

- What’s an example of when you’ve seen me exhibit this behavior?

- To confirm I’m correctly understanding you, is this what you’re saying?

- What’s an example of what “good” or “killing it” looks like?

- Who do you think is awesome at this?

- What would you expect as a 10% improvement?

- How does this affect your view of my overall performance?

- If you were me, what’s the first thing you’d try to change?

11. Stop chasing themes to stay unbiased.

Zooming out to synthesize themes is the quicksand phase of user research. While collecting (often conflicting) ideas, founders, PMs and marketers can get bogged down in both customers’ biases and their own — from hidden preferences to spotting patterns where they don’t exist.

Zoom’s Jane Davis is a worthy guide to help you get out of your own way. “Humans are so good at finding patterns, often to our own detriment. More often, we find patterns where we shouldn't,” she says.

- Put potential themes in a parking lot. If you've gone through three interviews and you start thinking, “I'm starting to hear a theme around this topic,” try creating an ongoing synthesis document, instead of waiting until the end. “That’s where I put those might-be-a-theme-but-I-haven't-validated-it-yet kind of things,” says Davis. “Writing it down makes me more cognizant of the fact that it is appearing in my head.”

- Don’t chase themes. “As much as possible when I start hearing themes, I don't chase them. I don't change my interview process at all,” says Davis. “I ask the same questions and keep the same structure, even as information is coming in, unless I’m doing rapid iterative, evaluative testing and updating prototypes in between sessions.”

- Push yourself in the opposite direction. “The next thing I ask myself is what would need to be true of the next several interviews for me to feel like this wasn't a theme? And I will oftentimes seek out information that goes against what I've heard to pressure test it,” says Davis.

If I think I'm hearing a theme around recruiting being the most difficult part of a research project, I will deliberately go in the opposite direction and say, “Tell me what the easiest part of recruiting is,” so that I'm giving people the opportunity to give me an answer that I'm not expecting.

12. Use this framework to hire the right VPE.

After more than 20 years in tech, eight companies, and thousands of hires, Shopify's Farhan Thawar has solidified a framework for snagging a VP of Engineering.

“I’ve found that candidates must be skilled in all three classic areas: Process: What occurs when? People: Who’s involved and how are they motivated? Technology: What will we use to get there?” he says. “The order of importance of these will change over time — a failure to adjust these profiles and fine-tune the hiring search is where most startups run aground in my experience.”

From the skills that are most important, to the red flags to watch out for in interviews, his full framework is a must-read for anyone approaching this hiring search. Here’s a preview of the interview questions and qualities he recommends probing for:

Process: Experiments with the development process, reduces admin burden, focuses on continuously delivering value to the customer.

- Describe the development process at your last company. What would you try again and why? What would you not try again and why not?

- Describe a shitty system at your last company. What did you do about it?

People: Attracts candidates and creates pipeline, makes the team more valuable for having worked there, gets energy from helping others succeed.

- How do you keep track of the careers of the folks you’ve worked with previously?

- Describe a time when you felt a superstar should leave your team to go to another.

Technology: Isn't afraid to ask tough or deep questions, stays unbiased toward their own experiences, trusts the team but can play tie-breaker.

- Give me an example of how you dig deeper into a project your team is tackling. Are there certain questions you like to ask, or approaches you’ve found to be effective here?

- What technology have you recommended in the past that you no longer recommend?

13. Bring in reinforcements to level up your executive team meetings.

As first-time founders wade into the executive meeting waters, strong waves can toss them around. So we reached out to some of the sharpest startup leaders we know for their best piece of advice on running executive meetings. A few of these folks pointed to a hidden undertow — a lack of founder enthusiasm for running the meeting. “It’s important for CEOs to be honest and self-aware. Do they actually enjoy this process of crafting the agenda, thinking about the flow, and keeping folks on track? Or do they have an allergic reaction that feels unnatural?” says Anne Raimondi, COO of Asana.

Early on, Zach Sims realized he fell into this same trap at Codecademy.

I find a lot of CEOs are not good at running an executive team meeting. For a while, I owned the meeting because I thought it’s what I had to do, even though I wasn’t good at it. I learned pretty quickly it was the wrong approach.

Instead, he tried rotating responsibilities across the executive team each week, which didn’t quite fix the problem. “We thought that it would help everyone feel a sense of ownership in the meeting, but it became a nightmare because you had no continuity between meetings each week,” says Sims. Eventually, he passed on ownership to his Chief of Staff and found the pieces click into place.

If you’re not quite ready to bring on a Chief of Staff, try this idea from HackerOne CEO Marten Mickos. “We have what we lovingly call a Rotational Chief of Staff — a director-level person who organizes the weekly exec meeting for one quarter, then hands over the task to the next person for another quarter. This adds orderliness and spice to the meeting, and provides that quarter’s Rotational Chief of Staff a unique insight into how a company operates,” says Mickos. (Without the discombobulated effect that might come from rotating ownership weekly.)

14. Create space for practice.

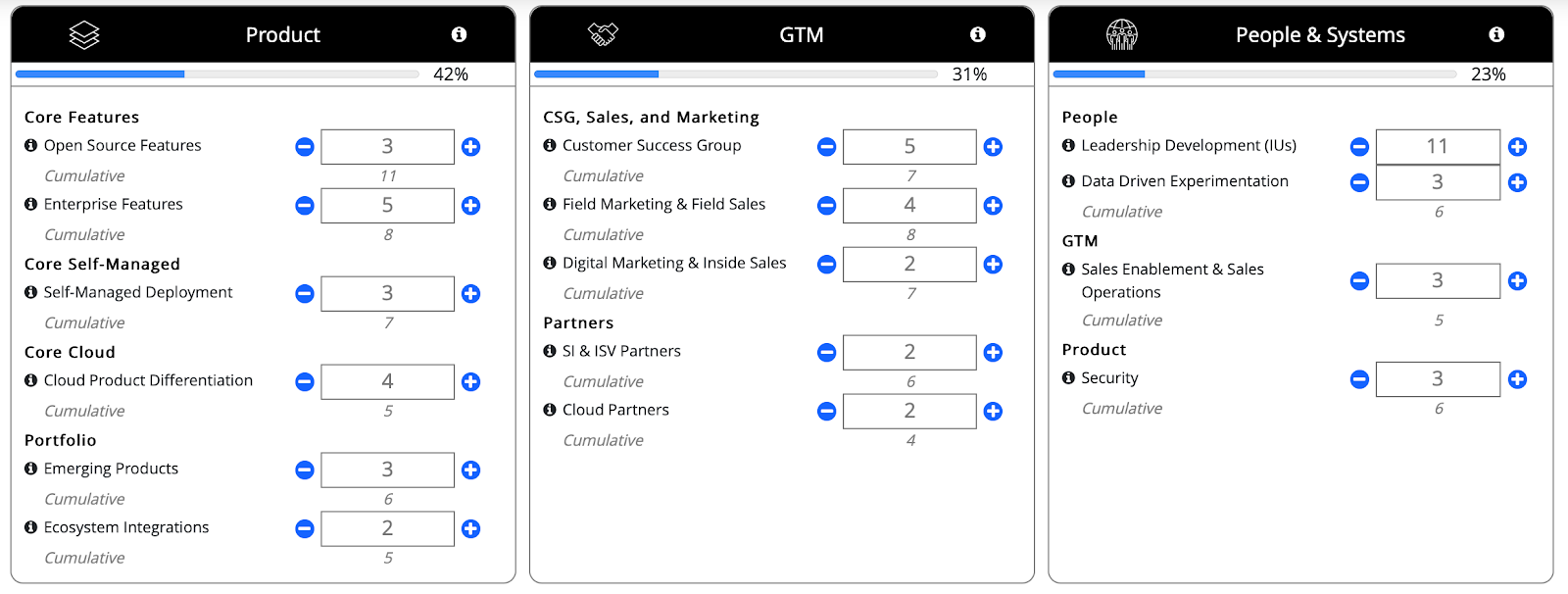

When describing his role as Chief of Staff at HashiCorp, Kevin Fishner keeps it simple: “My product is the company.” (We’re quoting directly from his LinkedIn page there.) Last year on The Review, Fishner made a stellar case for why the systems side of company building should get more attention, charging founders to “care about your first 10 systems as much as you care about your first 10 hires.” He went on to outline how his company set up three specific systems, including strategic planning.

HashiCorp’s strategic planning process centers around scorecards (see his template here) and an annual summit. But what’s most unique is that the offsite is focused on a business simulation. “Taking a simplified view of the company, we essentially build a game board based on our five-year financial model and this year’s three executive focus areas,” says Fishner. “We break folks up into teams of six, and they get to be the ‘CEO’ or the executive team for two days. Each round, your team gets to determine what initiatives to invest in. But there are ‘wobblers’ in the game, which are events that come up to throw you off track so you have to make a decision about how to adjust.”

“The essence of this exercise is the notion of practice. I grew up playing competitive soccer. We practiced four or five times a week and had games on the weekend — basically spending 90% of the time practicing and 10% of the time actually having to perform,” he says. “But when you get into a work environment, that notion of practice gets lost. So the simulation is about creating room for practice and making mistakes.”

To bring that spirit to your startup in a more scaled-down version, here are Fishner’s suggestions: “Bring a smaller group of leaders together for an offsite. Create an exercise where you're sitting in someone else's shoes and going through one of their day-to-day activities, such as answering support tickets,” he says.

A setting for practice, making mistakes, and building up empathy for what other people are going through is key to any annual ritual.

15. Bookmark this email copy to reinforce a bottoms-up culture.

As CTO at fintech startup Plaid, Jean-Denis Grèze sums up his engineering leadership philosophy with just one word: pragmatism.

“When I was younger, I liked the idea of building a perfect system and engineering something really perfectly. And that’s nice in the world of computer science and engineering and in the abstract, but pragmatically, you’re at a company with a budget,” says Grèze. “You have a timeline by which you need to deliver something, or your competitors will deliver something faster. You have a lot of constraints. And in that world, great engineering is about solving business problems faster and better than your competitors can.”

To stay on top of the snags that inevitably crop up, Grèze deeply values an ownership mentality. “The best leaders act like no problem is outside of their purview. It doesn’t matter if it’s a business problem, a design problem, an engineering problem, or a legal problem. They push through and find a way to get groups of people to solve the thing,” he says.

But like any cultural ethos, this doesn’t happen by accident. “It might be surprising that my most common answer to a lot of organizational issues that come up is to just say, ‘Hey, that’s great, why didn’t you tell [insert the name of the right peer] about it? You need to solve it with that person.’ I want the leaf nodes across various functions to figure out 90% of the more difficult things on their own,” he says.

I write multiple emails a day that basically say, "Thanks for telling me, I appreciate this as an FYI, but I don’t understand why you and this other person can’t solve this on your own.”

16. Ask these questions to surface the 360 feedback you need to hear.

After 20 years of executive coaching, Alisa Cohn has come to spot several traps that even seasoned founders and CEOs can fall into. (Her new book, “From Start-Up to Grown-Up” is chock-full of advice for scaling your leadership as the company grows.)

Her go-to recommendation is to run a 360-feedback process, preferably with someone else collecting the feedback on your behalf. “Even if you’ve been scrupulously honest about your inner life and thoughtful about your natural style and current state, you may come across to people quite differently than you think you do,” says Cohn.

You are the expert on your intentions. Everyone around you is the expert on your impact. Leading effectively is about marrying intention with impact.

Here are the questions Cohn asks when leading 360-reviews for an executive:

- What do her strongest allies say about her?

- What are her strongest strengths?

- What do her harshest critics say about her?

- What are her development opportunities? Her weaknesses, blind spots, and obstacles?

- When she is trying to influence you, how does she do it?

- How do you describe her leadership style?

- What environments bring out the worst in her?

- Do you think she's more external facing or more internal facing? Do you think it's the right balance?

- What specific behavioral suggestions do you have to help her be a better leader?

17. Treat customer development like a 1:1 with a direct report.

“Of the startups I’ve helped launch, the most difficult task has always been to take an alpha product and iterate until it begins to find traction.” Ryan Glasgow wrote these words back in 2013, and it still holds true. The key to unlocking this traction unsurprisingly requires talking to customers to get their take on what you’ve built so far (something his startup, Sprig, is purpose-built for).

Here’s his tip for making better use of this precious time: “The main goal is to help us understand what is or isn’t working here. I treat customer development as a 1:1 with a direct report — you just want to ask the hard questions,” he says. (This reminds us of Review favorite Julie Zhou’s mandate to make sure that all your 1:1s feel a little awkward.)

Here are Glasgow’s go-to questions to deepen the conversation:

- What are the highs and lows with our product right now?

- I was meeting with the head of product at one of our largest customers the other day, and right on the call I asked him, “Zero to 10, How satisfied are you with Sprig as a company? And help me understand what we could do to get you to a 10?”

- What's one feature you wouldn't be disappointed if we removed?

18. Want to get into public speaking? Hone your signature topic with these 2 questions.

Across different roles and career stages, plenty of folks have New Year’s resolutions to invest more into their personal brand — and opportunities are more accessible than ever, whether it’s joining virtual conference panels or hopping on the more casual Clubhouse stage. But there’s an endless sea of topics that you can cover — finding the right one can feel like plucking a particular grain of sand from the beach.

Anjuan Simmons, Engineering Coach at Help Scout, has carved out a robust side hustle as an oft-booked public speaker. Simmons pulls from his own experience getting started with public speaking and walks us through a couple of question prompts to help pin down your signature topic:

- When you were starting your career, what were the things that you struggled the most to understand? “Basically any answer to this question is a great talk, because every day someone is entering this industry just like you, and they’re struggling with the exact same things. What slowed you down? Some of my early technical talks were about setting up a stable development environment, ways to solve or debug common development problems, or how to write pull requests. These are nuts and bolts topics, but they’re still incredibly powerful, especially for people newer to software development.”

- Are there speakers in your field who you look up to? What do you think makes this speaker so great? “My goal here is not to have them copy/paste that person, but to deconstruct the core elements and then bake those elements into their own style. Some of the speakers I look up to are Lara Hogan, Erica Stanley, Saron Yitbarek, and Patrick Kua (just to name a few) because they talk about problems that I encounter every day and can clearly (and often cleverly) explain actionable solutions that I can implement right away.”

19. Set hilariously aggressive deadlines in the early days.

More often than not, the stories that snag headlines gloss over the messier moments in the startup trenches. “Behind the scenes, almost every founder story is the same: work tirelessly on an idea, do all kinds of crazy things that don’t scale, struggle to find traction, iterate and pivot before finally hitting on the thing that has product/market fit,” says first-time founder Tara Viswanathan. “But these are the inside stories you won’t find in the press releases, which often chop off the first years of chaos.”

Indeed, it took plenty of false starts and pivots before she achieved liftoff with Rupa Health. Viswanathan’s advice to other founders? Put a premium on speed. As an example, the Rupa Health co-founders challenged themselves to pivot and launch a virtual clinic platform in just one month — which Viswanathan admits was a ridiculously ambitious timeline. “We did all kinds of things to meet this deadline, from cold emailing doctors to join the platform to sourcing patients on Instagram. When you put extreme constraints on yourself, you get creative,” she says. “No one believed it was possible to create and launch a fully-functioning medical clinic in one month without a full-time engineer on the team, but we did!”

Viswanathan highlights three important reasons to set inconceivably short deadlines in the early days:

- 1. Build only what’s necessary: Aggressive deadlines help separate what’s a need-to-have from a nice-to-have. Your MVP should be about getting to the core of the problem you’re solving, not architecting exactly what the final workflow will be.

- 2. Get to the learning as fast as possible: At this stage, it’s about learning, not scaling. Write down why you’re running this experiment — what do you hope to learn about the problem?

- 3. Protect yourself from falling in love with the idea or product: Products and ideas should be disposable at this stage. Like any relationship, the longer you spend with it, the harder it is to let go even if it’s not working. Don’t get stuck in a sunk cost fallacy because you were too precious with your ideas.

You must create hilariously aggressive deadlines for yourself, otherwise, you’ll get swept away in unnecessary details that aren’t actually mission-critical. If you’re thinking about color schemes and button widths, your timeline is too long.

20. Brainstorm around the customer's needs, not your skill-set.

When compiling a list of the best, must-read books from 2021, “Working Backwards” surely makes the cut. Former Amazon execs Colin Bryar and Bill Carr open up about the “invention machine” — the processes, values and systems that enable the company to launch a wide range of new businesses, from AWS to the Kindle.

"Most companies take a skills-forward approach saying, 'Hey, we're good at e-commerce,' or 'We're good at retail,' essentially looking for adjacent businesses to build that leverage the strengths they already have," says Carr. "Frankly, I was taught this when I was in business school. But Amazon succeeded by taking a contrarian approach."

Jeff Bezos tasked Carr and his then-boss, Steve Kessel, with the challenge of building a digital media business back in 2004. "We had probably more than 50 different ideas. The standard approach would have been for us to go build our own knockoff iPod and iTunes competitors. But we intentionally did not focus on that because we wanted to invent something new on behalf of customers to create real value," says Carr.

"When we came up with the idea for the Kindle, we had never built a hardware device as a company. We sold tons of electronics as an e-commerce retailer, but we certainly had no capability to build one. And I remember questioning our wisdom at one point, like why on earth would we go build our own device? But instead of taking a skills-forward approach, we said 'What would be the product that, if we could create it, customers would love it?"

Design around customer obsession first and foremost — then you can seek out and develop the skills you need to get there.

21. Build your podcast strategy with interviews, not ads.

With millions of listeners plugging in their headphones and tuning into podcasts, brands are quick to follow consumers’ attention. Typically, they enter the podcast space as an advertiser — think, “This episode is brought to you by... Hello Fresh!” But with the ever-growing popularity of podcasts, these quick ad spots don’t come cheap.

So when Tom Griffin joined the Levels team, he leveraged a different approach. While still in closed beta, rather than spend thousands of dollars on ad reads or trying to spin up their own podcast show, Griffin started pitching to get the Levels founders as interview guests. After just six months, the founders had appeared on more than 100 podcast interviews, with well over a million people spending (on average) an hour learning about why the founders started Levels and the problem the business is solving. Dive into his playbook for the details of how they pulled this off.

Podcasts are an opportunity to spend an intimate 60 minutes in the ear of thousands of people who have opted in to listen to you alongside a host they trust.

22. Throw “purple flags” to interrupt bias in the moment.

Kim Scott is something of a legend — she’s the brains behind Radical Candor, which spawned a Review article that racked up millions of views, with a simple and powerful framework that’s become shorthand for effective management. She eventually expanded that Review article into a bestselling book. In 2021, she followed Radical Candor up with a new book — “Just Work: Get Sh*t Done, Fast & Fair,” which focuses on tackling DEI challenges in the workplace.

She also teamed up with DEI expert Trier Bryant to craft specific, straightforward frameworks to help companies put the principles of the book into practice. For leaders, that starts with creating the conditions where folks feel an obligation to call out bias when it happens, people harmed by bias feel they won’t be further punished for pointing it out, and people who demonstrated the bias don’t feel attacked when it gets flagged.

Interrupting bias is not something leaders can simply outsource.

To start, the Just Work team advises creating a shared vocabulary they call bias interrupters. “It could be a phrase or a word that your team or organization uses to identify bias in the moment — like ‘purple flag,’” says Bryant. “So if you’re sitting in a meeting and someone says ‘Hey, I’m throwing a purple flag,’ everyone knows that there was some bias that cropped up.”

But what happens next? “The norm that we recommend is if you're the person that might be being flagged or the person who is exhibiting that biased behavior, say, ‘Hey, thank you for pointing that out. I apologize.’ You note it and then you can correct that moving forward,” says Bryant. “But a lot of times we actually may not understand it. So then the norm should be, "Hey, thank you for pointing that out. I'm not quite sure I'm understanding what you're flagging, but let's talk about it after the meeting and keep going.”

23. Nail executive transitions to avoid “hero to zero.”

Whether they’re stepping into an existing pair of shoes or carving out a brand-new role, new startup leaders often face a dose of skepticism from the org. “Whether we intend it or not, a lot of people have a wait-and-see approach. We're excited about them, but is this going to work out? Versus having a vested interest in helping make that person successful,” says Anne Raimondi, COO of Asana. Her impressive career includes executive roles at SurveyMonkey, eBay, Guru, including board seats at Gusto and Patreon.

Way back in my eBay days there used to be a term people would use for new execs, which was hero-to-zero. How fast is a new exec going to go from hero to zero?

Placing new leaders on firmer ground starts during the interview process. “I firmly believe that no one should meet their new boss on the first day of the boss's job. That's such a terrible experience,” she says.

There may not be time to squeeze in 1:1s with each team member, but fitting in a group presentation or even a lunch-and-learn is critical to start building trust and avoiding the hero-to-zero trap. In these forums, Raimondi likes to ask people for feedback on two fronts: What they would be excited about with the new leader, and what they're concerned about?

Next, connect the dots between the new hire and their team. “Share all of that feedback with the person you hire. It may just be, ‘We didn't learn X about the person, or in their last role, they didn't have responsibility for Y.’ And then you can do a risk mitigation plan for those areas. Giving input, seeing output and getting updates on their progress — then it becomes less of a wait-and-see if this person's going to be successful,” says Raimondi.

24. Fund the winning boats, no matter what the calendar says.

Looking back on the 13-year journey of building Twilio, CEO and co-founder Jeff Lawson has been committed to scale from the beginning, including looking beyond the “next big thing.” “We don’t think about things as the next big bet, because I think that you need to have five or 10 or 20 bets,” he says.

Here’s why: “In the early days of those ideas, it's really easy to get married to the next big thing and all run towards it. Instead, you need to think that there are many things that could potentially be the next great thing. Treat it as a learning exercise, not yet a business exercise measured in dollars and cents,” says Lawson.

As founders juggle multiple experiments it’s easy to overlook the part that comes next: what to do when it’s not a swing and a miss, but rather a base hit. In Lawson’s experience, putting more firepower behind the bets that seem to be taking off is trickier than it might sound.

“One of the common mistakes that we, and I'm sure other companies, have made is that you fully allocate your budget at the beginning of the year. You’ve got five people working on one idea, five working on another, and one of those things is just taking off. And when they ask for more resources, leaders often say, ‘Well, it’s April, we do budget allocation in December, so we’ll talk to you in December.’ What a great way to starve an idea because of an arbitrary budget cycle on your calendar,” he says.

You’ve got to send people out in different boats to explore new ideas, but when you see the signs of success, make sure you’ve got the ability to double down in real-time on the winning boat.

25. Ask why it won’t work before making a decision.

When we interviewed Persona’s Rick Song last year, we touched on a range of subjects, but there was one common thread: his reliance on pre-mortems, or the act of thinking through why a particular product idea, strategy or candidate might not work out in the future.

“‘Why would a customer not want this?’ is often a far more interesting question than why they would. When you're working on a product idea, there's a thesis for why you believe you’re right and it's really easy to constantly confirmation bias yourself into believing it’s the optimal decision. But once you can also find the counterpoint, the scenario where you’re wrong, you can start teasing out when it would start to make sense — the point at which it will work.”

Oftentimes the question of why something won’t work uncovers the element that actually does make it work.

Here’s a few quick hits on how he applies this technique:

- For hiring: “The best hiring advice I received at Square was that when you're about to extend someone an offer, you're thinking to yourself, ‘There’s so many problems this person can help us solve, they’ll be amazing.’ And this almost certainly will be true. But it's actually far more helpful to think about all the ways in which this person may not work out for your organization — who on the team they might not interface well with, the types of projects they may not succeed in,” he says.

- For selecting a framework: “At an early-stage startup, you'll be bombarded with advice. You'll hear that X company did Y and it was so successful, or this strategy works so unbelievably well, whether that be OKRs or frameworks for product decisioning, like jobs-to-be-done. All of this advice is correct — given the right context,” he says. “What's much more interesting than figuring out how to execute this framework perfectly is discovering when it does not apply and finding that saddle point,” says Song.

26. Ditch stop-start-continue to reframe career growth.

As a repeat Chief People Officer, Colleen McCreary has more than 20 years of experience, from Zynga’s journey from scrappy startup to public company, to her current role at Credit Karma. And there’s plenty she’s changed her mind about in that time.

“I grew up in the culture of giving corrective feedback and working on all the things that you're not good at. Then I read this book ‘Nine Lies About Work.’ And one of the concepts they discuss is how we need to stop spending so much time on weaknesses and start focusing on strengths. Why do we spend all this time trying to convince or mold people into what they're not?” says McCreary.

“Instead, we should encourage people to strive for being even better at what they're already naturally good at or what they enjoy. It’s a very hard change for a lot of leaders — myself included — to move to that because of a natural tendency to pick out the things that aren’t going as well, or the other skills you think they need to advance.”

Here’s how to start shifting your mindset: “In peer or upward feedback, you can switch your tools to focus on more prompting questions on how people show up and what their strengths are. For example, I worked with a coach who had me do this reflected best self exercise. It was this idea of going back to your peers and some people who you've worked with and asking them for examples of when you've shown up as your best self. When they think of your best work, what are those competencies?” she says. “The feeling that you have as an employee is so different than when you do a traditional stop-start-continue type of feedback exercise — it really does flip everything.”

27. When you level up from manager to director, learn to get off the floor.

Dig into Nick Caldwell’s resume, and you’ll see leadership posts at an enviable list of startup staples — Reddit, Looker, and now Twitter, where he is the GM of Core Tech. But some of the most formative leadership lessons came from his 15-year stint at Microsoft.

One of the thorniest transitions in this period for Caldwell was the quantum leap from engineering manager to director. “Up until this point in my career, I loved line-level engineering management. I carried that through to my role as a director, even though I had like 30 people reporting to me. I did all the things that you would expect from someone with a much smaller team — I got to know everyone individually, and worked hard to motivate and inspire people on a one-to-one basis. I was having trouble scaling all of the things that are great about being an EM,” says Caldwell.

To close the gap, Caldwell’s manager gave him a mantra that Caldwell now passes along to other folks making the manager-to-director transition. “One day he said, ‘Nick, you have to learn how to get off the floor.’ What he meant by that was if you think about the engineering team as a warehouse production, you’ve got your line managers and then you’ve got your directors. The directors have to be off the floor, overseeing multiple lines,” he says.

His manager took an additional step to hammer home this point to Caldwell. “He made me stop sitting with the teams directly to force me to get a bit of removal from the day-to-day. It did teach me how to delegate more effectively,” says Caldwell.

When you get off the floor, you can see systematically how your teams are working together and better spot the bottlenecks from that vantage point.

28. Match your first marketer to the founding team.

Over the course of her career, Maya Spivak has fielded plenty of questions from founders diving into marketing for the first time. She’s got a wealth of marketing experience that runs the gamut of nearly every specialty. Prior to heading up marketing at Mux, she was a product marketing leader at Wealthfront and the second marketer at Segment, where she ran brand marketing and communications.

One of the most common mistakes she sees founders make? Lumping all of these marketing specialties together, rather than plucking out the pieces that are most applicable to their startup. Depending on the specialty, a marketer’s day job can include anything from drafting a press release, A/B testing website copy, teaming up with sales to craft personas, or interviewing customers for testimonials (just to name a few).

To borrow from “Ted Lasso,” all people are different people, and all marketers are different marketers. Figure out which kind of marketer works best for your startup.

For starters, Spivak recommends sizing up the founding team. “It’s all about assessing the current strengths that exist on the team and the highest priority gaps to fill, prioritizing based on the immediate needs of the company. You may have founders who are particularly creative and design-oriented, which means you have beautiful websites and really delightful brands built out before a marketer even gets there,” says Spivak.

“That means you don’t necessarily need to find a marketer who is spiking out on the creative dimension, because you’ve already solved for that internally. Instead, you can focus on finding a marketer who’s more analytical. Or if you’re struggling to explain a more technical product, you’re looking for a more technically adept marketer who's going to translate the brilliance of your product into digestible marketing materials,” she says.

29. During the discovery phase, run the cheapest test of all: An email campaign.

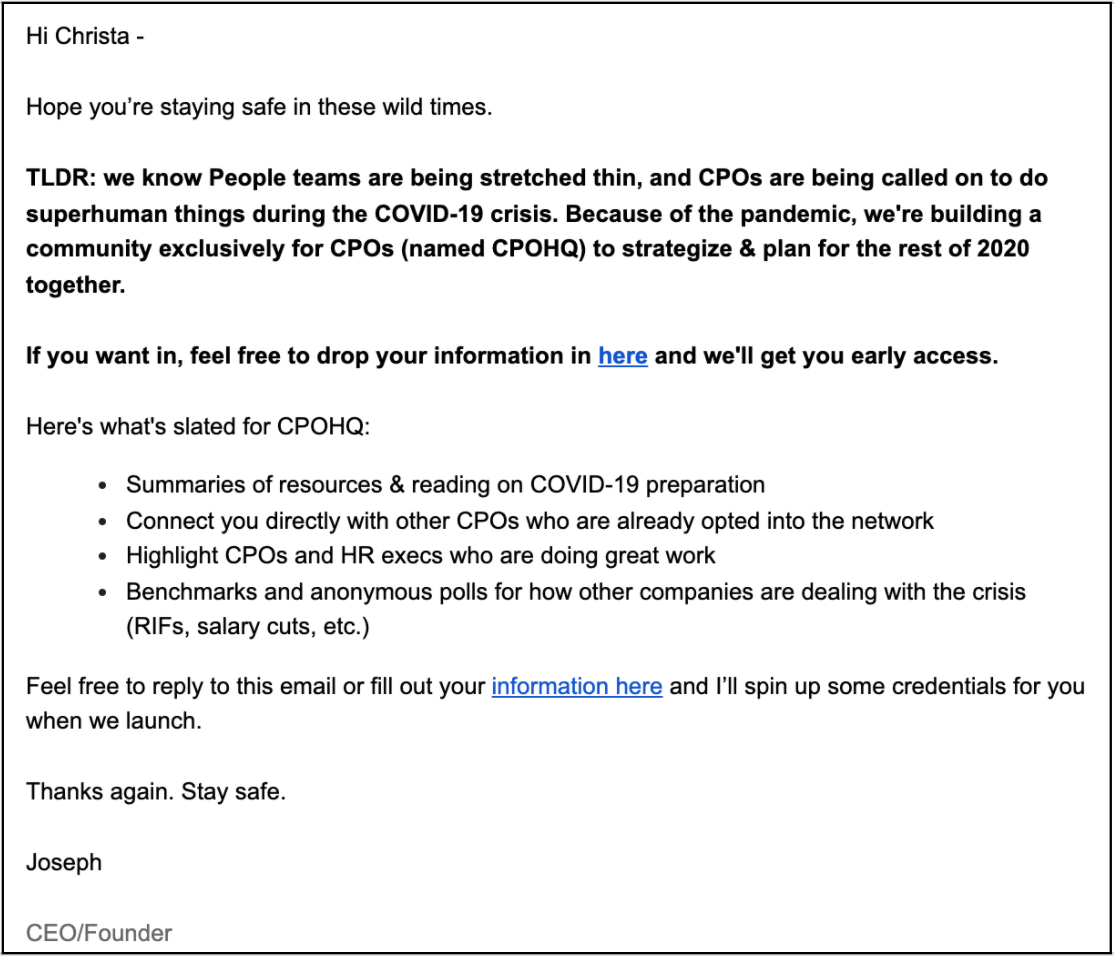

Like plenty of startup founders before him, Knoetic founder & CEO Joseph Quan was having a tough time finding product/market fit. His previous company, focused on HR & people analytics, had just gone through a team rebuild, lost several key customers and had just six months of runway left in the bank. Then, to top it all off, March 2020 hit. “All of a sudden, no one was interested in people analytics anymore. They were just scrambling to understand how to respond to the existential threat of COVID.”

To keep the company afloat, it was time for a big pivot. But rather than go heads-down, trying to come up with his next big idea, Quan spun up a quick test to validate a few different ideas the team had kicked around. “We queued up several outbound email campaigns targeting Chief People Officers, advertising different ideas we were considering building: A tool to help analyze the impact of layoffs, a remote work productivity suite, and an exclusive community for CPOs. We hadn’t built any of those things yet, but we knew we could build any of them within a month,” says Quan. “The idea was just to validate the demand for a new direction. As it turns out, the email campaign advertising our community idea got higher engagement than any email I’ve ever written in my life. Something like 40% of the C-Level executives we reached out to responded to the email. It was clear we had a winner.”

With that conviction, over the course of the next 12 months, that kernel of an idea evolved into a community called CPOHQ, counting over 1,000 people executives from companies like Roblox, Glossier and Figma as members.

30. Get customers to the right place instead of forcing a sale.

Product-led growth was something of a trendy topic in 2021. Kate Taylor has built a career at Dropbox and Notion centered around finding the balance between sales and product, making her the perfect guide — whether you’re at a sales-driven startup that’s intrigued by self-serve, or at bottoms-up businesses pondering how to layer on sales.

We were most struck by her perspective on navigating these strategic transitions. “The team that I ran at Dropbox was called inbound sales. At first, it was part of the sales org, but we eventually realized that wasn't a good place for it. So we moved into the marketing org, took quotas away and started to make it more of a value-driven effort to answer questions and get people to the place they need to be. And that often may have been over to the sales org, but it could have pushed them into the self-serve flow or over to support,” she says.

Once we discovered that interacting with customers should be more of a value-driven conversation — that we should be getting customers to the right place instead of trying to force a sale — that was when things just started to click.

But you can’t rely on just a gut feeling that things are coming together — it’s not only about getting customers to the right place, but also testing to make sure they’ve arrived. “Once we got a little bit more intelligent with how this team was operating in between go-to-market and product, we ran experiments where we held out a set of control customers and compared them with a variant group to test if these conversations were driving value,” Taylor says. “We’d motivate the reps more on C-SAT or CES and less on revenue, and then see what happened compared to the control. And we saw a considerable lift in revenue. Reps were motivated off of having value conversations and answering the quick slam dunk questions that customers had.”

Top illustration by Alejandro Garcia Ibanez, featuring (from left) Anjuan Simmons, Anne Raimondi, Hareem Mannan, Colleen McCreary, Farhan Thawar.