A decade ago, Gokul Rajaram fundamentally changed the way he makes decisions. Then a product management director for Google AdSense, he was presenting to Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt. A gnarly challenge related to Google’s display ads business surfaced, and the discussion got heated.

Schmidt’s voice boomed, “Stop. Who’s responsible for this decision?” Three people — including Rajaram — simultaneously raised their hands. “I'm ending this meeting," Schmidt said. "I don’t want you to return to this room until you figure out who the owner is. Three owners means no owner." With that, the meeting was adjourned and the team dismissed.

Ten years and three companies later, Rajaram still recalls and references that moment. Now at Square, he oversees Caviar, the company’s rapidly growing restaurant delivery service. Before that, Rajaram led the strategy and execution for Facebook’s advertising products after it acquired semantic technology startup Chai Labs, which he led as co-founder and CEO. At Google, he played a leadership role in building Google AdSense into a multi-billion dollar product line.

Throughout his career, Rajaram has noticed how a lot of forward-thinking companies still gravitate to consensus as the way to make decisions. It turns out that for important, difficult choices, that approach is often ineffective and impractical. At First Round’s last CEO Summit, Rajaram shared a framework that he uses at Square and Caviar to make the most difficult decisions, all while assigning ownership, being inclusive and coordinating execution among all stakeholders.

Consensus means no ownership. What’s important is not that everyone agrees, but that everyone is heard and then the right person makes a decision.

Why Difficult Decisions Deserve A Framework

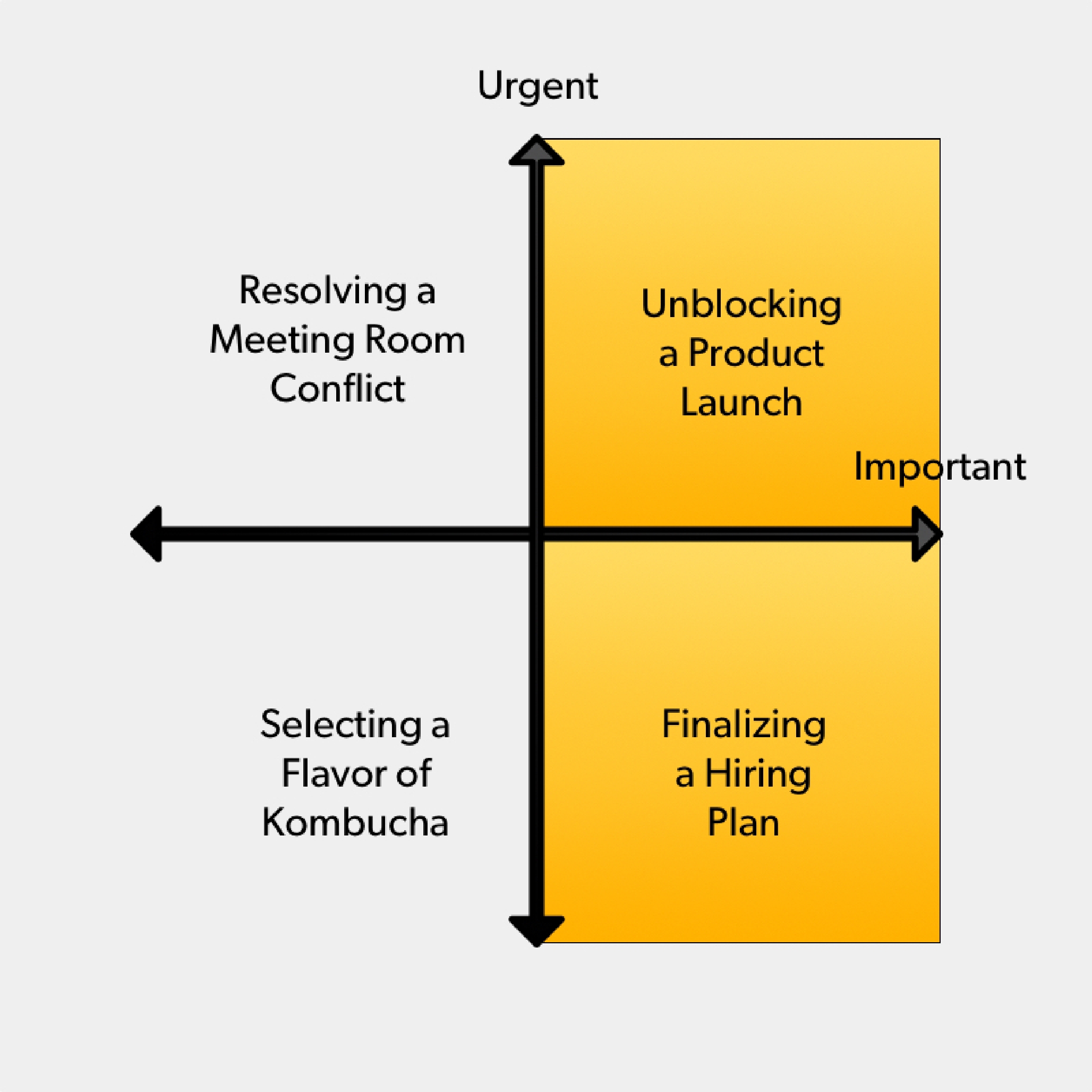

The decision-making framework that Rajaram uses assumes a tough choice must be made. For Rajaram and his colleagues, that means first recognizing when a decision is hard. “This may be a familiar chart for some. It sorts decisions into four quadrants along the axes of importance and urgency,” says Rajaram. “As a team or organization, substitute your own description for each quadrant so that it resonates with your people. My favorite’s the Kombucha quadrant: the non-urgent and non-important decision. We jokingly reference the Kombucha scale at Square when prompting colleagues to consider how important or urgent a decision is.”

This basic chart can help establish shared definitions of priority and ideally relegate scenarios to ballpark categories that’ll help determine how you’ll invest resources to make the decision. “The difficult choices that you want to run through the following framework are the important ones — whether urgent or non-pressing. “The right decisions for this system are those that are so critical that they could affect your company, even make or break your business. That could be at the company, group or business unit level.”

For most leaders, this exercise is instinctual, but this quick quadrant sorting can help communicate that categorization and bring others up to speed on the decision at hand. “Once you do a quick assessment of the importance of your choice and start using the decision-making framework over and over, something happens. You realize that making decisions doesn’t take days. It can be done in an hour or two. In that time, you can quickly make a high-quality choice with this framework. A fast decision means you can conserve energy for the important work that comes after making the choice,” says Rajaram.

The decision-making framework is called SPADE, an acronym that stands for Setting, People, Alternatives, Decide and Explain, which was created by Rajaram and Square colleague Jeff Kolovson.

Here’s how each step is important and how it’s been applied in the companies where Rajaram has had to make important calls. (And check out this new toolkit Rajaram developed to make implementing SPADE even easier.)

Setting

Every choice needs a context, so the “S” in SPADE stands for setting. “The ‘setting’ texturizes your decision and establishes the tone. It helps to figure out what the decision actually is,” says Rajaram. “It breaks it down into elements and sets the participants in the decision into motion.” The setting has three parts: what, when and why. Here’s how Rajaram describes each element:

Precisely define the decision to capture the “what.” “You’d be amazed at how many people can't articulate what the decision is in a precise way. For example, I've seen decisions articulated in the following manner: ‘The ‘what’ is figuring out the next country to launch in.’ If you have exactly one product, that’s okay. But if you’ve got multiple products, the decision is not just what country to launch in, but what product to launch and in what country to launch it. It's two axes not just one — and if you dig deeper, there’s probably more dimensions to the decision. Be very precise about the choice you’re making.”

Calendar the exact timeline for the decision to realize the “when.” It must reflect not only the duration it’ll take to make the choice, but also the reason why it’ll take that amount of time. “Be sure to think critically about the ‘why.’ If someone says a decision must be made by October 15th, 2015, why must that be? Does it matter? Here’s an example: The product needs to launch on November 15th, 2015 and therefore I need the name determined by October 15th, so this name can flow through in the collateral, into the website and into the app. I need four weeks for that. That logic helps people understand the when, and the ‘why’ of the ‘when.’”

Parse the objective from the plan to isolate the “why.” Articulating the “why” is the key to establishing the setting. “The why defines the value of the choice. It explains what you’re optimizing for and reveals why the decision matters. I'm an advisor to a startup at which the head of product management and the head of product marketing had a massive blow-up. They disagreed about how to price a product. Working through it, we realized the conflict stemmed from a fundamental misalignment around the goals of pricing. The product manager saw it as a way to optimize market share, while the product marketer viewed it as a way to maximize revenues. Neither of them had articulated that, nor had the company’s founder. As soon as we figured out this was the root of the conflict, it became easier to get to the decision.”

How can you make a decision without knowing why it matters? It’s a simple, basic question, but I’m astonished by how the answer so often eludes people.

People

The horsepower behind executing a decision is the people, representing the “P” in the framework. “The reality is that I lied. Setting is not the first thing you need to make a decision; it’s People. But it’s also less fun to name a framework PSADE,” says Rajaram. “The truth is that — as with everything in an organization — people come first. This includes those who are consulted and give input towards the decision, the person who approves the decision, and most importantly the person who’s responsible for ultimately making the call.”

There are three primary roles for people involved in the decision: Responsible, Approver and Consultant.

Synonymize accountability and responsibility. Some decision-making frameworks separate the responsible from the accountable person, but the decision maker (aka the responsible person) should be both. “At Square, the person who's responsible for making the decision is the person who's accountable for its execution and success. We believe accountability and responsibility are the same thing,” says Rajaram. “Here’s why: think of the last time you were handed a decision that someone else made but for which you had to execute and usher to success. How did that feel? I’d guess it made you feel frustrated, powerless or disengaged. We want to avoid that. That’s why the decision maker is both accountable and responsible. It’s more fulfilling and empowering.“ Empowering people means pushing decision making authority to the person who is accountable and can own the decision.

Veto decisions mainly for their quality, not necessarily their result. A key participant in the decision-making framework is the approver. “The approver is the person who can veto the decision. Typically, the approver does not vote down the decision itself, rather they veto the quality of the decision,” says Rajaram. “It is a checks-and-balances function on the responsible person to make sure she is not abusing her privilege and making a low quality decision. Vetoing a decision a superpower that needs to be used very sparingly, but also not forgotten to be flexed when needed.”

Formally recognize the roles of all active participants. The third key role is the decision-making process is that of the consultant, who plays a very important function that many forget to acknowledge - giving input and feedback. “People don't realize that a lot more people need to be listened to across the organization. Consultants are people who are active participants in the decision,” says Rajaram. “These are people who’ll give input, feedback, analysis and support to the responsible person so she can make a high quality decision.”

At Square, consultants are known and named, given their influence and insights during the decision-making process. “I remember one instance that had to do with the change in policy for how engineers wrote unit tests for software. The decision maker, an engineering lead, had consulted with several of his fellow engineering leads and felt comfortable with his decision. Then he sent an email with the policy update decision to all of Square’s engineers,” say Rajaram. “Within 30 minutes, a dozen people replied, many of them disagreeing vehemently with the decision. To his credit, the lead took ownership. He froze the decision and invited every engineer at Square who agreed or disagreed with the decision to meet with him over the next week. I think a dozen people took him up on it and went to his office hours. A week later, he sent his new decision out by email. Guess what? It was exactly the same decision as the last time. But this time, nobody complained. Why? Because they all had been listened to.”

Listening matters. Much, much more than you think. People want the option to chime or chip in, even if their stance is counter to the end decision. They just want to be listened to.

Alternatives

Once you define the setting and assemble the participants, your next step is to outline the alternatives. “Simply put, an alternative is a view of the world. It’s the job of the responsible person — the decision maker — to come up with a set of alternatives to consider, without any bias. Alternatives should be feasible — they should be realistic; diverse — they should not all be micro-variants of the same situation; and comprehensive — they should cover the problem space,” says Rajaram. “In other words, the decision maker needs to list out the pros and cons of each alternative as it relates to the value function. In many situations, one can also quantitatively model out the impact of each alternative and evaluate it against the decision’s setting — specifically the why, the optimization function.”

For many complex decisions, it’s best to generate alternatives in a group setting with all of the Consulted people. “Get in a room, get on a whiteboard, and brainstorm,” says Rajaram. “For each alternative, list out the pros and cons, as well as the parameters behind the quantitative model. There are no shortcuts. Get into the numbers as much as possible. It can be very hard with ambiguous decisions to get down into the numbers, but it’s very valuable to do so.”

Most importantly, if done right, this brainstorming exercise will also help generate new alternatives you might not have considered earlier. For example, he says, “When we were in partnership discussions with an important potential partner, the process got stuck around a specific clause. The decision we needed to make was how to move forward. We had two initial options — go ahead with the partnership as-is or terminate the discussions. When we got together to brainstorm alternatives, the group was able to generate a third compelling option — establish a contract with a third party which would mitigate our risk around this clause — that we had not previously considered.

“The place where we see timely, quantitative evaluation done best is in M&A deals. Why? Because it’s a very important decision that’s potentially ‘make or break’ for the company,” he says. “Plus, most experienced corporate development professionals do an amazing job of evaluating the sell, buy, and partner scenarios along with the associated economic benefits to the company over five years or ten years. They consider probability of success, resources invested and opportunity costs.”

Employ the level of diligence, metrics and stakeholder engagement as you would for an M&A deal. If it’s a big decision, you’re actually merging your past and present.

Decide

With the alternatives evaluated by your people and pros and cons anchored to your setting, it’s time to decide. “The way you choose is simple. Now that you've figured out all the alternatives, bring all the consultant folks back into the room and present everything. This involves listing out the alternatives, their pros and cons, and the values from the model you ran. Then ask them for their feedback,” says Rajaram.

The most important part part of this process is to ask them to send you their vote privately. “It can be by email, Slack or, my favorite, SMS — as long as it’s delivered privately along with the chosen alternative and why it was selected,” he says. “Casting your vote privately is important because difficult decisions can have controversial solutions. Your goal is to get honest declarations, not answers that bend to organizational hierarchy or peer pressure. It's really important to solicit impartial feedback and votes that aren’t influenced by others.”

That said, in exceptional circumstances, choices can be articulated openly. Rajaram remembers the decision-making process that Sheryl Sandberg ran was so thorough that she built an unprecedented level of trust within the group. “It started when we elected her the decision maker and owner, one of the smartest moves we made. Then she involved us at each stage, insisting on our involvement. By the time she got us all in the room the third time, she had built such a high level of trust in the room that everyone, including Sheryl's exec admin, felt completely free to speak their minds."

Now that the decision maker has all the votes, they should evaluate the information thoughtfully, consider people’s votes, and then make the decision. This involves choosing one of the alternatives, and writing out in as much detail as possible, why they chose it. “Writing out the decision shouldn’t be too hard because you’ve already listed the pros and cons and the formula,” says Rajaram.

Explain

The final step of the framework requires the decision maker to explain the decision. In short, she must articulate why she chose the alternative that she did, and explain the anticipated impact of the decision. This process is much easier if the decision maker records her thoughts as soon as she makes the decision. This stage involves three steps:

Run your decision and the process by the Approver. Again, the default of the Approver should be to monitor the decision process, not result. “Since the decision maker is leading the SPADE framework, it’s likely that the approver has not been as involved, and therefore can evaluate the decision with a fresh perspective. If you’re responsible for the decision, meet with the Approver, explain the decision, and get buy-in. If you created a high quality decision framework, she’s unlikely to veto it.”

Convene a commitment meeting. It takes coordination, but it’s important to pull together all the consultants that have been involved in the decision. Reserve a conference room or line that will include all participants to date. And then walk them through the decision. “Now is when you explain the decision and really take ownership of the decision. There might be grumbling or disagreements, but this is the moment when you explicitly become the owner of the decision,” says Rajaram.

Call a commitment meeting. After the decision is made, it’s paramount that each person — regardless of being for or against the result — individually pledges support out loud in the meeting. “Go around the room and ask each one of them to support the decision one at a time,” he says. “Commitment meetings are really important, because when you pledge to support a decision in the presence of your peers, you're much more likely to support it. As the decision maker, you’re responsible for executing on that decision, and so you need their support to help to move forward.”

After a decision is made, each participant must commit support out loud. Pledging support aloud binds you to the greater good.

Circulate the annals of the decision for precedent and posterity. Now that the decision is made, the real work begins. “After the commitment meeting, you need to to figure out how next steps will be delegated and executed,” says Rajaram. “The decision maker must summarize the SPADE behind the decision in a one page document. This brief should be emailed out by the decision maker to the rest of the company or to as broad of an audience as possible. Why? Because the company needs to see what and how decisions are being made.”

Square uses an email alias (notes@) to send all kinds of decision and meeting notes to the company. “We started sending SPADE summaries to the company over the last couple of years,” he says. “It's been really gratifying to see the number of decisions that are increasingly made using this framework and sent out to the company. Employees start to register the high quality decisions that are being made about important topics across the organization. That’s how more people get encouraged to confront difficult decisions and share how they made them.”

Pulling It Together

The SPADE decision-making framework can help synchronize and speed up collaboration to make difficult choices. While the system outlines a step-by-step process, Rajaram emphasizes a few key takeaways. First, don’t use consensus; agreement does not equate ownership. Second, clarify the ‘why’; it’s essential to understand the purpose and context for making the decision to optimize for it. Third, ensure that the decision maker is both responsible and accountable for the final choice. Don’t be that company where decisions are handed off to be implemented without previous involvement. Fourth, consult maximally. Many more people want to be involved than you think do. Finally, get feedback privately, but document and get support publicly.

“I bet you if you survey people at your company today about decision making and their level of happiness, most will say that they don't understand how decisions are made. This framework allows you to articulate each stage of the process broadly to a company,” he says. “I firmly believe that making high quality decisions can fundamentally transform the way we work. I personally can't wait to live in a world where people and companies make difficult decisions systematically and in a high quality way.”