Founders often know from a young age they want to start a company. David Cramer created a product so successful that it pulled him into being a founder.

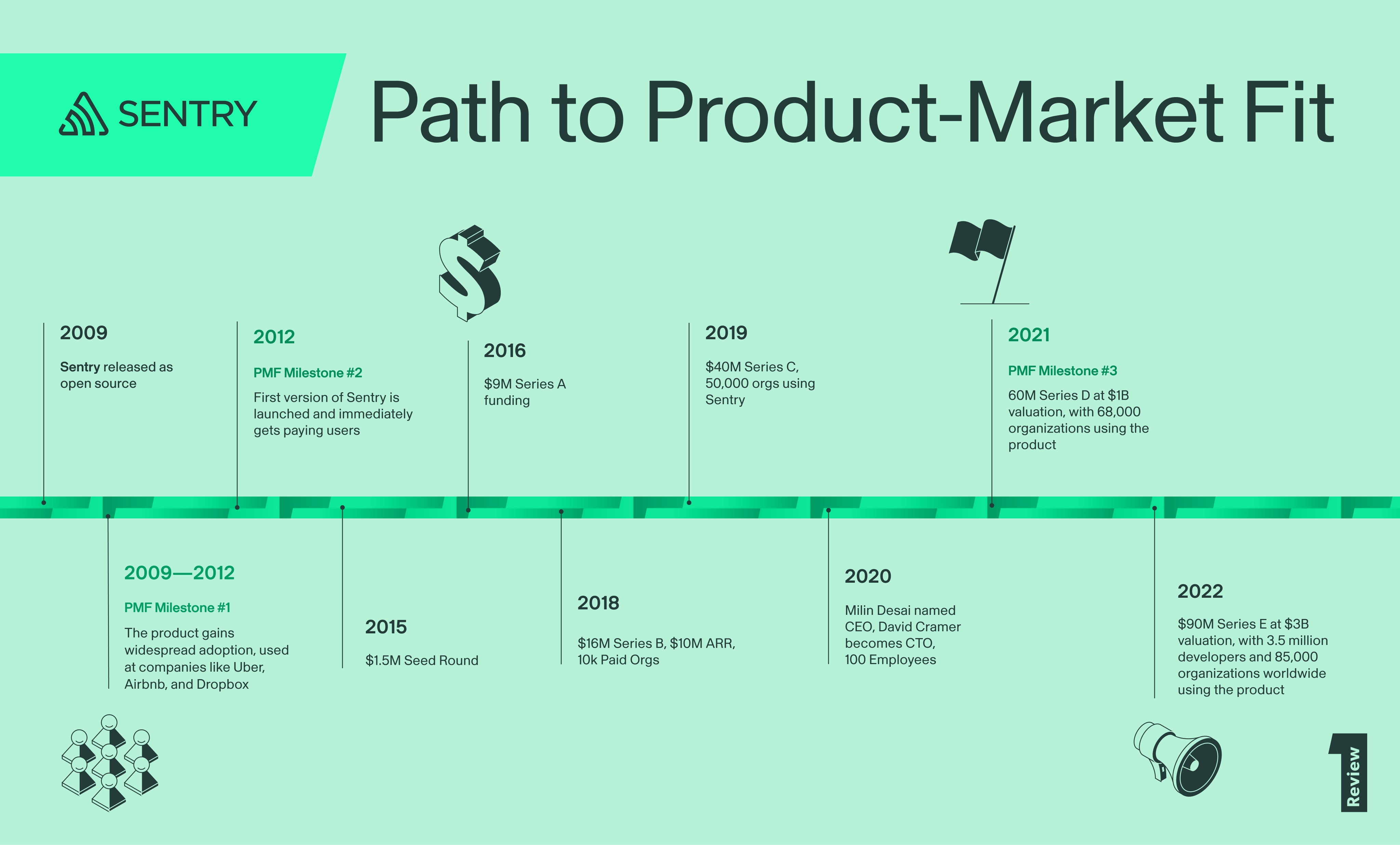

The Lincoln, Nebraska native grew up working class, dropped out of high school in ninth grade and worked at Burger King. He taught himself to code on borrowed computers, spending a lot of his free time playing early internet games, in awe of their seemingly endless creative possibilities. That interest led him to the world of open source, and ultimately resulted in a project that would become Sentry: an error and performance monitoring software platform now valued at over $3B, used by more than 140,000 customers and millions of engineers around the world.

Unpack the Cinderella story and what you’ll find is a founder who has remained true to himself and his beliefs, guiding the company in his image. He champions focus, saying “no” to anything that doesn’t align with the company’s vision (even if the opportunities are lucrative). He’s ultra-competitive, wanting “nobody else to exist” and adjusting the company’s tactics to squash competition. Even the company’s marketing reflects his spirit — believing the founder is the brand, and that marketing’s only job is to make people know you exist and what you stand for.

In this exclusive conversation, Cramer shares how his working class upbringing instilled traits that would lead him to succeed. He also discusses the pivotal decisions in Sentry’s journey to product-market fit, why he decided to fundraise when the company was successfully bootstrapped, the call to replace himself as CEO in 2020 and much, much more. It’s a fascinating and candid look at a founder who’s unwavering in his conviction and has truly done it his own way. Let’s dive in.

The scrappy beginnings that forged Sentry’s relentless founder

Cramer dropped out of school his freshman year, feeling he didn’t fit into the classroom structure and wasn’t getting much out of it. “I was that rebellious kid,” he says. “I didn’t like school. My parents were pretty loose so they let me do it. I went to work at Burger King for a couple of years, got promoted to manager — I fired my cousin.”

When he wasn’t cleaning out the deep fryer or terminating the employment of blood relatives, Cramer was indulging his obsession with burgeoning computer technology; from a young age he’d been fascinated by the internet, but didn’t have a computer at home. “I have vivid memories of going to school an hour early just to surf the internet, or going over to my friend's house all the time to use the computer.” These were the early days of being online: GeoCities, Hamster Dance, the wild west of creation. Cramer was captivated by the limitless possibility.

“That led me into games: data mining games, building databases out of them, basic programming. A lot of my early career was just me hacking stuff together,” he says. “I’d take World of Warcraft game files, reverse engineer them to pull out all the items in the game and build a database out of those so people could search them on the internet.”

Cramer credits the open source community as a catalyst for almost everything that followed; he was publishing his work freely, building tools for others to use and collaborating in public.

Access is a big deal when you come from the middle of nowhere. Sentry was born out of these opportunities. But even outside of Sentry, every job I’ve gotten was because they used my code already.

The first door to open was a full-time job as a programmer. He went from managing the Burger King in Nebraska to working for a startup called Curse in Germany, which was big in the World of Warcraft scene, making gaming content and virtual currency.

“Startups are a more accessible version of technology companies,” he says. “I was a high school dropout, nobody was going to recruit me from an Ivy League school. And so I always worked in these smaller companies and grew and developed my skills with them.”

While still working for Curse, Cramer relocated from Germany to San Francisco for a year, before eventually leaving that role and returning to the Midwest to plot his next move. As much as he felt at home in Nebraska, surrounded by family and friends, he soon realized his hometown couldn’t compete with the gravitational pull of Silicon Valley. “I recognized the personal value to me of being surrounded by peers,” he says. “And no matter what anybody says, there’s no other place like San Francisco that has that.”

An open source project becomes the seed of Sentry

It was 2008, and Cramer’s call to make the move back west proved to be the right one. Returning to San Francisco, Cramer joined a startup called Disqus, a (since acquired) audience engagement platform, immersed once again in a tight-knit developer community. “It was the defining moment of my career,” he says.

Over the next three years, he ran large parts of the Disqus infrastructure, wrote significant portions of the product's code and began speaking at developer conferences, building both his reputation and confidence. He also started learning Python. "I was big in the community. Instagram, Eventbrite and Mozilla were all Python Django companies. I think the code was public for all these things. There was a Django community channel, where we'd help and ask questions of each other."

Here, the seed of Sentry was planted.

“Somebody asked how I would log errors to the database. I thought that seemed pretty easy. I whipped up an example, pushed it on Google code, and didn’t think much about it — I just like tinkering,” he says. “I don't know if the value prop actually existed at the time, because the idea of putting logs in a dashboard in that way didn't make sense. But what did make sense was that I could take errors and get these really rich reports of data. The amount of information it gave me was phenomenal.”

Initially, Cramer wasn’t thinking about monetizing what he’d built. “I was like, why would I? I’m just building stuff I want my peers to use.” But there’s a bigger lesson here than just the returns that often come from generosity and being community-minded. Cramer gained deep insights from having people use his product so early, realizing people valued the depth of its error data more than he anticipated. It also showed hard proof of consumer demand, and it put Sentry on the fast-track to product-market fit. “I was always motivated by people using my stuff,” he says. “I was happy to spend my nights and weekends fixing things, getting feedback. I still live off of that stuff, it really feeds me.”

“That, to me, is definitionally how you get to product-market fit.”

The conversation with a Heroku peer that changed everything

For the first few years, Sentry existed only as open source — but had gained significant traction. It was running inside thousands of companies, including Silicon Valley heavyweights like Uber and Airbnb. But turning it into a business still wasn’t part of the plan.

“I never thought about it until one day I was talking to a PM at Heroku, who told me I should launch a paid add-on of Sentry, because they were trying to expand the add-on store,” he remembers. “I didn’t quite understand what it meant, but I thought I’d make a little beer money. That was the joke at the time, because Sentry already had a lot of adoption at that point.”

Over Christmas break, while still working at Disqus, Cramer decided to experiment. “I built a cloud service, added Stripe on it, and launched it.”

The results were immediate. Sentry had a paying customer on day one, ten within a few days. “It was all organic. We only charged seven bucks. But there was clearly value being delivered. The demand was there.”

That early enthusiasm was the proof point, which mirrors how Cramer defines true product-market fit.

My version of product market fit is when a customer viscerally reacts in a positive way. The counter version of that is, ‘oh, that seems useful.’ But no emotion. No excitement. Something's wrong there. It's not clicking.

Still, at that time, Cramer still saw Sentry less as a business than a self-sustaining side project. “The money was used to pay for servers or sponsor conferences. We didn’t have income out of it for about three years.” But it was becoming harder to ignore the signal its growing customer base was sending. “We had great product-market fit from the get go. We still had a lot of work to do to unlock everything, but it was there.”

Weaponizing open source

Sentry’s user base was growing fast, but there was a catch. Those thousands of Silicon Valley companies already running the open source version? They had internal engineering teams capable of self-hosting copies of Sentry’s open source code, so they weren’t going to pay for a cloud-hosted service.

It soon became apparent to Cramer that the right move was not to chase existing users and convert huge companies, but rather to target the next generation of startups. Engineers who had used Sentry at Uber, Airbnb or elsewhere would take it with them to their next company — and this time, those younger startups would choose the convenience of the hosted cloud version. “None of the companies using the early open-source version ever converted to cloud,” Cramer says. “We went after the long-tail funnel of what would happen over 10 years. That worked phenomenally for us.”

Some of the large companies did ask for a paid, on-premises offering, but Cramer refused. “Uber actually did pay for a year for a support contract — it was a lot of money. We chose to not renew it. I didn’t want to sell on-prem software. I didn’t want to be in that business.”

Instead, Sentry doubled down on the strategy that had already been working for them: giving the product away for free. Despite having a paid, cloud-hosted version of Sentry, letting companies self-host for free meant the product could spread organically across the developer ecosystem. By refusing to wall off the product, Cramer used openness as a weapon. “That’s what open source does — it commoditizes the market,” he says.

He recalls one telling example, when a payments company switched from a now-defunct competitor to Sentry’s free, self-hosted version. “They didn’t pay us a dime, but it took away 10 or 20 percent of that competitor’s revenue,” he says. “Less than a year later, they paid us half a million dollars a year. Not only does that competitor not exist anymore, but we don’t really have competitors, we removed the market. We got this customer with zero marketing or sales dollars spent.”

For Cramer, the story illustrates what he calls his “ultra aggressive” approach to competition. “I’ve been capable of building Sentry because I’m very competitive. I want nobody else to exist,” he admits. “For a long time, we had a bunch of competitors that looked exactly like us. None of them exist anymore. That’s not a coincidence. That wasn’t us just focusing inward and ignoring them. It was me, every day, being like, ‘we have to be better in every single way, in every single territory they’re in.’”

That instinct for relentless improvement has defined Sentry’s strategy. When one rival began gaining traction in the PHP Laravel open-source community (a popular web framework used by millions of developers to build modern applications) Cramer refused to concede ground.

“We can’t have that. We have the better product, the better engineering. Overnight, we went from barely existing there to being the clear leader. We even hosted the first official party at the conference so everyone knew who we were,” he says.

This aggression has never mellowed, and he advises early stage founders to be just as assertive over their turf. “If a startup enters our space today, the executive team is immediately focused on them,” says Cramer. “You can’t let anyone wedge into your market. That’s how you lose the thing that made you successful in the first place.”

Even when competing with giants like Datadog, his posture remains the same: don’t replicate — innovate.

Our strategy is to do what they can’t, not to feature match. You don’t compete by building the same product. You compete by building the one they can’t.

One example of this was when Cramer noticed that while legacy monitoring tools were still obsessed with back-end servers, the real action was moving to the browser. JavaScript was powering a new generation of dynamic web applications, and this came with a new set of visibility problems. “We recognized the JavaScript shift,” he says. “Everybody else ignored it. That was the point zero of the entire company: we have to solve JavaScript first, because we recognized that was the growth of the industry.”

While other companies chased enterprise clients and traditional back-end monitoring, Sentry went after the developers struggling with JavaScript errors happening live in users’ browsers. The market might have looked smaller, but it was rapidly expanding. By meeting that emerging need early, Sentry didn’t just find a niche, it defined one. “We only exist because people ignored the space. We might still have grown, but we are dominant in that market. We are first to market in everything there. We are still first to market in everything there.”

From bootstrapped to backed: the decision to raise capital

In early 2013, Cramer made the decision to leave Disqus. Within months he’d joined Dropbox as an engineer, continuing to run a steadily growing Sentry as a side hustle. Two years later, in early 2015, Sentry had what most founders would consider a dream setup: thousands of paying customers, $600K in annual revenue, and profitability. But Cramer wasn’t content. “We were so much bigger than our competitors, but we were barely in the black,” he says. “We wanted to hire people. We wanted to grow. We wanted to win. We wanted to be the best — and to be the best, we needed more money.” In the years since he’d first built Sentry as an open-source tool and later turned it into a paid cloud service, Cramer had begun to imagine something larger: transforming a useful developer tool into a serious player in Silicon Valley. To do that, he knew, would require more than hard work and luck. It would require capital.

Why fundraise when you’ve got a successful bootstrapped business? The answer was, to do something you can’t do otherwise.

It was around this time that Cramer began to feel the friction between Sentry, and all the ways he envisioned being able to grow and evolve it, and his responsibilities at Dropbox. “I was doing two full-time jobs at once. I was on call for both. It was a nightmare. I realized it was unsustainable.”

Cramer left Dropbox and focused on fundraising for Sentry, but didn’t know much about it. Early attempts to raise a seed round went nowhere. In hindsight he can see that he didn’t really know what he was doing; he was cold-calling, and had no experience in how to pitch VCs, or navigate the VC world generally. “Those people were not going to give me money,” he says. “All of them basically ghosted me.” It wasn’t until a former Dropbox colleague, Dan Levine, reached out that things began to shift. “He knew who I was, and it turns out that’s the game: bet on people you already know.” Within months, Sentry raised a $1.5 million seed round. Their Series A followed the next year, bringing in $9 million.

The cash infusion changed everything, not just financially, but psychologically. “After one year of venture funding, it was clear we were the market leader. Before that, nobody had any idea who we were,” he says. “A venture partner pushes the company to do more. You have to think bigger.”

Still, he insists he wouldn’t change the fact that Sentry started out bootstrapped. The discipline of being forced to make money early taught him an important lesson. “When you're bootstrapped, you don't give things away — it's too expensive. When Sentry went from open source to a real company, there was no free plan. I don't know that if I had venture capital and I was building a product, I would make that same decision.” A pitch deck that lays out the plan for how you’ll eventually monetize is great, he says, but theory doesn’t always play out the way you plan. “Being bootstrapped forces you to validate with the customer.”

And for Cramer, that validation is non-negotiable for finding true product-market fit.

“If there's one thing anybody takes away from this, I’d say it’s to monetize right away, to recognize if it's gonna work or not.”

Staying narrow to scale: how “blind focus” drove Sentry’s success

For Cramer, a kind of tunnel vision he describes as “unwavering blind focus” has always come naturally, and he credits it with much of Sentry’s success.

Saying 'no' to things you don't believe in is really important. You have to steer those decisions, and have conviction they align with your vision.

In a decade of building Sentry, that conviction has often meant saying ‘no’ when saying ‘yes’ might have been easier, and more lucrative. At various points, Cramer faced pressure to expand the company’s scope, with pressure often coming from potential customers negotiating large contracts. But instead of chasing near-term wins, he stayed fixated on long-term alignment.

One example: Best Buy asked Sentry to complete an RFC (request for comment), a detailed technical proposal outlining how Sentry would implement and integrate the product at Best Buy. To some, it would seem like a request worth agreeing to, given it would lead to a promising path toward landing a major customer. But Cramer saw it differently: “It did not seem like the best use of my time,” he remembers. “I’d rather get 10 new customers instead of Best Buy. I said no.”

A similar story played out with an insurance company that was requesting specific anti-virus protections before signing. “We weren’t going to do that,” he says. “They did not become a customer at the time. But both of them are now.”

It’s a value that’s come to define Cramer: resisting the temptation to chase validation or revenue at the expense of focus. “I care about the banker that is gonna use the cloud, not the banker that refuses to use the cloud,” he says. He advises early stage founders to think on longer time horizons. “Early stage especially, it's easy to fall into the trap of needing validation. Needing to make some money.

You have to ask yourself: does that align with my view of the world? Specifically, you need to ask if something aligns with your view of the world in the future, versus in the past.

That discipline to stay narrow has proven to be one of Cramer’s greatest strengths. It’s also a source of tension, the constant balancing act between conviction and flexibility. “You need an extreme degree of confidence that looks like ego. At the same time you need humility.”

He admits it’s a contradictory balance, but one founders can learn to walk over time.

“You need to find middle ground; you need to be empathetic towards what matters. But you’ve also got to not question what you’re doing a lot of the time. That’s hard.”

By 2020, that balance led Cramer to a decision many founders struggle with: stepping aside as CEO. Milin Desai, former GM at VMware took on the role. “I am very confident in everything I say, but then, I gave up board control. I hired a CEO to take my job. I don't need the arrogance of the whole thing. I'm also very honest about what does and doesn't work for me.”

The same discipline that helped him ignore distractions also helped him recognize when his own role needed to change. “You’ve gotta have the humility to be able to say, ‘that opinion I held was wrong.’ For some people that's tough. But the people that have succeeded at Sentry are the ones who have been willing to challenge their opinions. Because the counter version is you just end up with decision paralysis.”

Bug reports and billboards: Cramer’s unorthodox playbook for sales and marketing

For Cramer, marketing has never been about selling features or function. It’s been about building a brand that people remember, even before they realize they need your product.

Sentry’s billboard campaigns are perhaps the most obvious example of this; quirky, eccentric, out-there imagery that turn heads with their strangeness, all the while communicating nothing specific about Sentry’s value offering. It’s just a vibe. Attention. Eyeballs. This illustrates perfectly Cramer’s philosophy, borne of his early experiences, back when existing Sentry customers using the open-source version couldn’t be convinced to convert to the cloud product.

Marketing’s job isn’t to fill a funnel. It’s to make sure people know we exist, recognize our brand, and understand what we stand for when the right moment comes.

Also central to his marketing philosophy is that the founder of a startup is central to its brand. “The founder is the brand,” he says. “Half of our weird campaigns come from me. If you’re a founder and you’re not out there representing your company every day, you’re doing it wrong.”

Cramer’s unconventional instincts extend to sales, too. He learned early that enterprise deals aren’t really about the product, but about trust. “Especially with large companies, they’re not really buying your software,” he says. “They’re buying a partnership. It’s not about selling features. It’s about showing that I know this space better than anyone else, that our company are the experts, and that we’re the best partnership they could ever have.”

This philosophy drove Sentry’s sales strategy in the early days. “I was basically being what I wish every product manager was,” he says. “I was writing the code, but I was also following up with every single customer.” When a bug report came in, he’d fix it himself, then personally email the user whose name was tied to the error. “If that happened to you, you’d be amazed,” he says. “That was just good user experience.”

Cramer’s instinct to be hands-on hasn’t faded with scale. Even today, he occasionally steps into deals himself. Once, when a major AI company struggled with setup, Cramer showed up at their office in person to help fix it. “That’s founder-led sales,” he says. “It’s not just talking to customers. It’s doing whatever it takes to make them successful with what you’ve built.”