Adam Pisoni, co-founder and CTO of Yammer, talks to a lot of tech leaders about building more responsive organizations. But his go-to success story isn’t about a mobile app or a hot SaaS product. It’s about a burger. In one particularly crucial meeting, he needed to convey the value of companies being flexible, rapidly adaptable — in a word, responsive. So he told a story about restaurant chain Red Robin.

“They released a new type of burger at a handful of restaurants, the Tavern Burger, and allowed servers to directly and instantly communicate with the product's creators on Yammer. This allowed kitchens to literally iterate on the burger within the same day based on what customers were saying,” Pisoni explains. With a change in communication, the company empowered its employees, responded immediately to customer feedback, increased their rate of experimentation and decreased the cost of failure. And they rolled that new burger out in four weeks — down from the 18 months it usually took to launch a new product. Pisoni’s story was a slam-dunk, and he got heads nodding about why organizations should be built for agility.

Incidentally, that meeting was with Bill Gates.

In this exclusive interview, Pisoni shares more tales from the vanguard of the responsiveness movement, and explains how a culture shift toward transparency, experimentation and empowerment can make companies more successful at any size.

TRADITIONAL MODELS ARE BROKEN

Most organizations, including the most tech savvy of startups, are working with a century-old framework, and they don’t even know it, Pisoni says.

The first modern companies were bureaucratic juggernauts like the East India Company, and their practices still prevail. When you’re running an empire, efficiency — not innovation — is king. For most of history, companies just needed to deliver products and services as quickly as possible to as many people as possible. Competition became about efficiency and scale, and the hierarchy of management we still use today emerged to divide the thinkers who had ideas and the doers who executed them. “You wanted the doers to have as little flexibility and empowerment as possible. They weren’t supposed to make decisions; they were supposed to execute their task as efficiently and predictably as possible."

“Efficiency is great if you can plan for the long-term,” Pisoni says. “If you know what you’re going to do for a long period of time, you can really get into the nuts and bolts of how to do it efficiently.” But because efficiency, by design, locks in roles, processes and practices, it also makes it much harder to change.

The minute the future becomes unpredictable, efficiency can become your enemy.

Flash forward to 2015, when the future is more unpredictable than ever. The connectivity we've achieved over the last decade has changed everything. “We moved from a world of information scarcity to a world of information ubiquity,” Pisoni says. Consumers are learning, sharing, adapting — and changing their expectations more rapidly. “The world formed a giant network. And that has accelerated the pace of change to crescendo.”

Still, a shocking number of companies are designed so they literally can’t change with the shifting tide of consumer demand. “The fundamental problem organizations face is that they can no longer keep up with their customers. The hierarchy and the network are smashing into each other, and organizations of all kinds can't keep up with the people they serve,” Pisoni says.

Consider an old-model company like Tower Records. They delivered value by making a wide variety of music available for purchase in a retail setting; they didn’t define their mission as delivering music the best way possible. So when MP3s took off, and they started seeing higher rates of next-day returns from rampant CD ripping, Tower could only work within its existing model: They adjusted their return policy and stopped accepting open packages.

“The minute the future becomes unpredictable, efficiency can become your enemy.”

“It would be naïve to think that no one inside that company saw the digital revolution coming or advocated for innovation. But the structure of their company locked them into traditional retail,” Pisoni says. This ultimately spelled their demise.

RESPONSIVENESS: THE NEW MODEL

Today, nearly every CEO agrees that companies need to be responsive, nimble, agile. Pisoni meets with a lot of business leaders, and he rarely encounters resistance on that point. “But the changes that agility requires are, simply put, really hard,” Pisoni says. The shift from the efficiency model to the responsiveness model is a cultural one — it means unlearning over a century of inherited instincts.

Time and again, Pisoni has seen that leaders’ first instinct are to tackle the shift with a big-picture mindset. “Companies want to attack the problem the way they’ve always attacked big problems: With a program, an innovation department, some sort of large-scale planning,” Pisoni says.

Before co-founding Yammer, Pisoni served as an engineering leader at Geni, Connexity, Cnation and Shopzilla. Yammer was bought by Microsoft in 2012.

This uber-shift from efficiency to responsiveness requires a new framework for making all decisions on a daily basis.

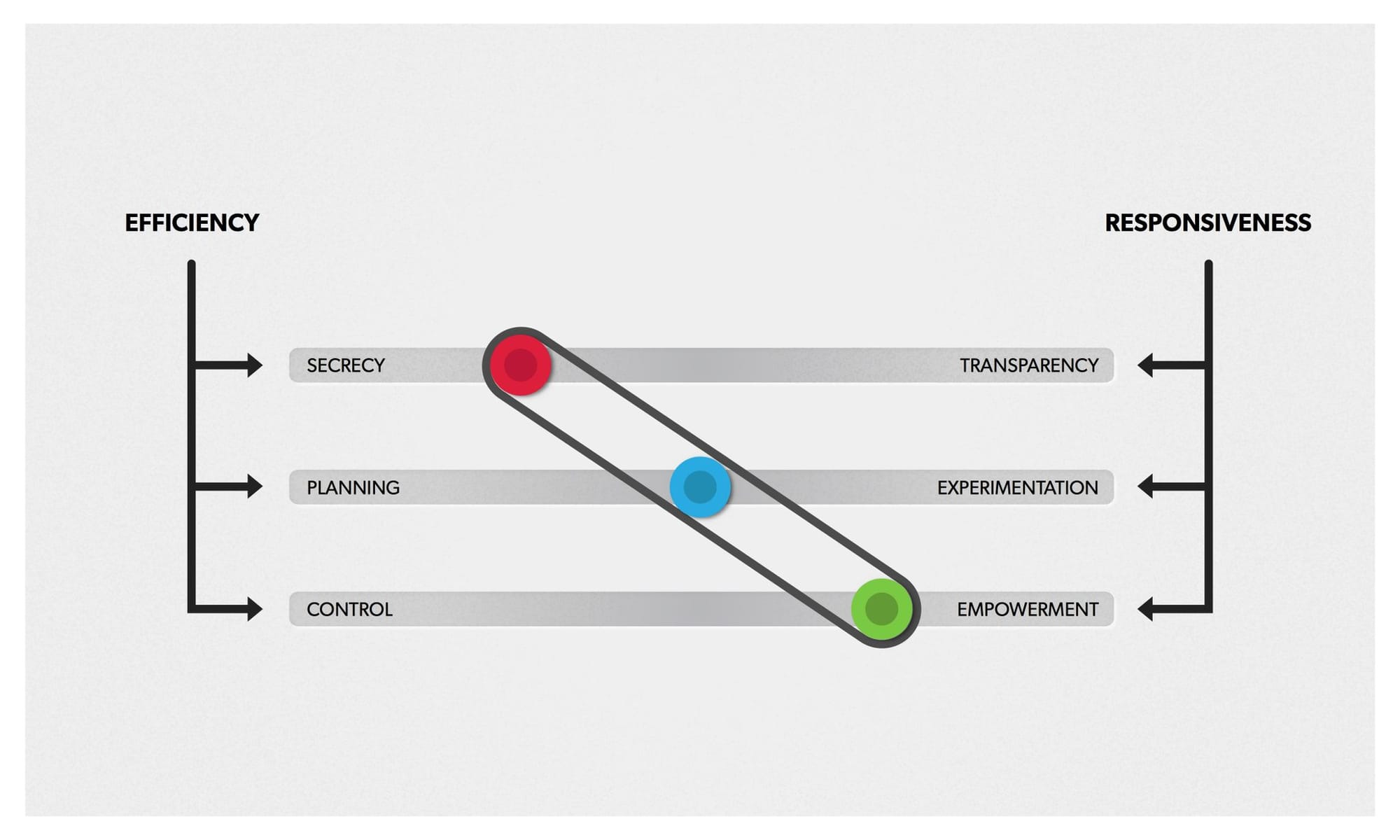

To help leaders get started, Pisoni shares a simple way to think about this new framework. Imagine three spectrums, each “tuned” with a slider (like on a music mixing board). Your company falls somewhere on each of these spectrums:

Secrecy vs. transparency: In the efficiency model, roles are prescribed, no one needs information beyond what is necessary to execute their piece of the plan. If you expect your organization to be more responsive, your team needs context — they need to know what’s going on in your company and in the market (think of the designers of the Red Robin Tavern Burger talking directly to servers). The rise of cross-functional groups demands that information be shared between team members to maximize the value of your organization.

Planning vs. experimentation: Efficiency stems from long-term planning — if anything went wrong, it was because you weren't able to predict and plan for it. In an era that demands you leverage the benefits of unpredictability, you need to create a culture of hypothesis-testing and quickly change course based on results.

Control versus empowerment: In the efficiency model, people are hired for a skill set, given a role, and then told how to execute it. Innovation isn't the priority; leaders simply want employees to implement a known plan. This is no longer the case. “When we say ‘empower,’ it doesn’t mean team members are empowered to do whatever they want. Everyone still has a role. But in the responsiveness model, they're empowered to innovate on how they deliver their value,” Pisoni says.

He demonstrates how it all comes together with a simple and persistent problem: Travel budgets. In the efficiency model, when travel costs need to come down, your instinct might be to lean on policies and control. If you’re spending too much on travel, it’s because you couldn’t predict what was coming up — so you’ll need to plan more. And perhaps there are too many options for travel, so you’ll want to rein those in, control them with an internal travel-booking portal that only works with certain airlines and hotels.

Now let’s look at travel budgets through the lens of responsiveness. In a world where you can’t predict what’s coming, you have to give up some control: New options like Airbnb and travel aggregators are cropping up every day, for example, and your team members might very well find cheaper options if left to their own devices. So empower them to do that, Pisoni argues — but make sure they’re sharing travel information with each other. Maybe they can split that Airbnb (or at the very least a cab). Pisoni’s team at Yammer tried this approach — pushing all three sliders far to the right — and reduced travel costs by 40%.

He’s the first to acknowledge, though, that a swift move toward the right of the spectrum may be very uncomfortable. You’re turning your decision-making framework on its head, and your “right-side” solutions might initially feel wrong. It takes practice.

“To start, I always ask people to pick a problem and get a piece of paper: On the left side, imagine how you might tackle a problem with maximum secrecy, planning and control,” Pisoni says. “Then on the right side, imagine pushing the boundaries of transparency, experimentation and empowerment to solve that same problem.”

Creating lasting change is about changing everyday decisions.

THE RESPONSIVENESS MODEL IN ACTION

For a dramatic example of how impactful — and relatively simple — the shift to responsiveness can be, Pisoni spotlights customer support. No department is more hamstrung by secrecy, planning and control in a networked world than the team on the front lines. Think about what customer service reps are up against, Pisoni says. In a world where any customer can instantly access an internet’s worth of information, many customer support teams are still working with constrained scripts handed down from management.

Insurance giant Nationwide puts a lot of stock in its customer experience, so they knew they needed to find another way. “They gave their customer service team access to people throughout the rest of the company. They can have conversations online with people in the product groups, payments, you name it,” he says. Ditching a rigid, formulaic script, they're able to go find answers to customers’ questions no matter what they are.

“One of the best stories they told me was about a customer whose RV broke down on vacation,” Pisoni says. “The local broker told him he wasn’t covered, so he called Nationwide corporate.” It was a complicated problem, and the customer service rep didn’t know how to solve it; in the old model, the case would have taken days. “The rep posted the issue internally, got colleagues involved from claims and product, and they figured out that not only was the guy covered, he was also eligible for emergency funds. He was on his way without a huge bill in three hours.”

Nationwide simultaneously experimented with a process, empowered a team and broke down barriers to transparency, illustrating a crucial past of the responsiveness model: Take another look at those sliders, and you’ll see that they’re all connected by a figurative “rubber band.”

“The three sliders aren’t sequential; they’re deeply interrelated,” he says. When companies try to move just one, it almost always fails. “Let’s say your company is all the way on the left, totally efficient, and one day you decide to make things totally transparent. You push that slider all the way to the right — but only that one. Well, now everyone in the company can see all the problems, but they have no power or resources to fix them,” Pisoni says.

Here’s another one Pisoni sees a lot: A company resolves to experiment more, but doesn’t touch the other sliders. Now you have a situation where team members are asked to innovate, but can't really take risks — in fact, they’re punished when experiments fail. “And with secrecy all the way to the left, nobody knows what experiments are happening, and they’re not armed with best practices,” he says. “Everyone is going off in different directions, with no communication.” Imagine moving just one slider, and that rubber band will bounce it right back to where it's supposed to be.

“You have to move the sliders in concert — and it’s not about moving everything all the way to the right,” Pisoni says. “It's about gradually moving, bit by bit, finding what works, and accepting that it's going to be really uncomfortable for everybody.”

BUILDING RESPONSIVENESS FROM SCRATCH

What about new companies that have yet to define their mindset? “Most startups don't think about how to build their company to begin with. They're focused on the product, and that's a mistake. It may work when you're three people, but it won’t when you get to 50 people,” he says. He sees the same errors get made a lot. An early-stage startup does away with processes entirely, then grows, realizes it needs more structure, then flips entirely to the old model of organizational thinking.

The job of startup leadership is to layer in responsive structure from the get-go, and deeply consider the framework they will employ. “Ask yourself, ‘How can I make my company agile through and through, and responsive through and through?’” Pisoni says. The key to both is iteration.

Most startups believe in iteration of their products. Now they need to apply the same thinking to their organizations.

“In 2015, if you go to your people and say, ‘Our product is a big experiment. We're always experimenting,’ they're not going to be surprised. But you're also going to have to say, ‘The organization is an experiment, too, so don't be surprised if it changes. We're working together on this.’"

Still, Pisoni isn’t advocating wholesale change — it’s about gradually shifting your approach to every decision no matter what it is. To start, just identify one problem, pick one team that’s bought into this process and enlist them to try something new. “Most startups don’t have a problem with empowerment, but they’re very opaque — so find out what happens when you make your communication more transparent,” Pisoni says. That might mean trying out a private social network, like Yammer or Slack, or hosting regular all-hands meetings or hack days.

“Startups are very familiar with hack days — you get so much done, right? So what would happen if you tried a five-week ‘hack day’ project?” Pisoni asks. Pick an objective your company has decided is important, get the necessary team members together, and establish the target but not the process. Have them figure it out using responsiveness as a guide.

THE VALUE OF RESPONSIVENESS

The notion of moving away from efficiency may be anathema to many startup leaders. It disrupts what many organizations see as their competitive advantage. Will you lose your edge if you invest in experimentation? Pisoni’s answer is a resounding no. “To be clear, I’m not against efficiency," he says. "I’m against the idea of long-term planning efficiency.” When we can’t predict the future, efficiency can no longer drive decisions.

One of Pisoni's favorite examples of a successful responsiveness model is clothing chain Zara, known for “fast fashion.” Their value proposition is making leading-edge trends available inexpensively. To deliver that, responsiveness is paramount. Consider a traditional apparel company. It’s made up of divisions, from manufacturing to design to distribution, and new products move through them sequentially. A new coat would start with the design team and it would be many months before a consumer ever laid eyes on one in a store.

Zara turned that model on its head. “They said, ‘When we want to create a garment, let’s take one person from each of those divisions and put them on a team.’ Sure, they come from design or distribution, but for that period they’re working on that garment, that’s their team,” Pisoni says. These cross-functional groups can quickly innovate across organizational boundaries — and they’re the reason Zara can get a garment from sketchbooks to shelves in two weeks.

But it doesn’t stop there. With these nimble teams in place, Zara’s leadership can enlist their front-line employees in a new way. “Now they can say to the salespeople on the floor, ‘Look, if you hear someone asking for a red coat a few times, tell us. Within two weeks we can get a small batch of red coats to you and see if they’re selling.’” Zara has built a channel to hear the voice of the customer and respond to it quickly.

The company also broke a tenet of manufacturing, Pisoni notes. They don’t run their factories at 100% utilization. They realized that running them at 80% meant that they could slip projects into the pipeline on short notice and ultimately sell more. “In some cases, you're getting less efficient, but it's OK because you can make more money by being more responsive,” says Pisoni.

By breaking down hierarchy and conducting smaller-scale, cheaper experiments, you can dramatically reduce the cost of failure and ultimately make your process both more responsive and more efficient.

“The best news is that — because we're still just figuring this responsiveness model out — we're at the low-hanging-fruit phase,” Pisoni says. This may not be true in another decade, but for now, even starting a group where people can talk about a burger yields transformative results. Small changes, and in many cases really easy ones, will move the needle. “That’s not the hard part. People are afraid because all they know is increasing control or planning. Right now, the hard part is trying something different and seeing what happens.”

He likens it to that old truism of education: Kids are born wanting to learn, but they lose that over time through the bureaucracy, process and rigidity of traditional education systems.

People are naturally innovative. They see the problems. They often have solutions. But companies beat it out of them.

In many ways, the responsiveness model isn’t about instilling something new — it’s about removing barriers. Give your team access to information, tools to experiment and the freedom to execute their role, and you’ll unlock untold willpower, bold ideas, and brand-defining originality. “It's usually not hard. It's actually pretty easy. Many companies trip themselves up because ‘easy’ is counterintuitive. But really, it's just a leap of faith,” Pisoni says.

So have a hack day. Try a new internal communication tool. Or implement one of the most transformative changes Pisoni’s seen: Open dialogue between leadership and the rest of the team.

Many of the companies he works with have begun to hold regular Q&As with their CEOs. “In every instance, employees love it. The CEO is blown away by the insight they get, too. And that’s so easy. It’s an hour of time once a week.” The shift toward responsiveness is mostly about reorienting your mental models away from the hierarchy and toward the network.

“Just take one step,” Pisoni urges. “Some things are easier done than said.”