The beginning of every year unleashes a frenetic rush of activity, from wrapping up performance reviews to finalizing budgets to starting on those plans for the quarters to come. Thankfully, the somewhat painful process of wrangling these inputs is worth the effort, as promotions, increased headcount and team building mandates are often just visible on the edge of the horizon.

But while many startup leaders are kickstarting these first few months with a refreshed focus on hiring, that tank full of shiny new year energy and enthusiasm often quickly runs out of gas. Newly promoted managers, old hats, and founders with fresh rounds of funding all eventually run into the same speed bump: hiring at early-stage startups is hard.

More specifically, it's a time consuming, nose-to-tail process. As cold outreach emails fly out, applications pour in and onsite logistics multiply, the experience of running a hiring process quickly morphs from a side gig to a seemingly full-time endeavor that monopolizes attention and clogs inboxes. From crafting job descriptions and building balanced candidate pipelines to sifting through impactful interview questions and dialing up references, every step requires careful consideration — and presents plenty of opportunities for process to unravel and dream candidates to slip away.

It’s no surprise then that managers and founders are constantly on the hunt for hiring hacks to ease the load. To help out where we can, we’ve rounded up six must reads with thoughtful advice, intentional strategies and a smattering of unconventional tactics to present a package of practices for every stage of the hiring process.

Read on for wisdom from those who’ve beaten down the recruiting path and come out the other side with a fresh perspective. We hope you can draw inspiration from their habits as you tinker with your own hiring efforts and look to deepen your well of motivation for all the months that still lie ahead.

1. Go on a hike to set your hiring vision and give out tests, not pop quizzes.

Dan Pupius spent six years at Google before moving on, first to Medium as Head of Engineering and then venturing out as co-founder and CEO of Range. But to this day, Pupius feels that he snuck through Google’s intensive interview process. And his experience recruiting others to join the tech giant validated this feeling, as he observed plenty of false negatives (people who could have been amazing contributors) and false positives (candidates who checked all the academic and meritocratic boxes but weren't the right fit after all). That’s why he and his colleagues at both Medium and Range set out to craft meticulous hiring rubrics and remove blind spots from their respective recruiting systems. The unexpected part was that they ended up relying on the principles of product development along the way.

For example, setting out a clear and compelling vision is critical to the development of any product. For hiring, it’s just as important. But many founders start with a rather weak vision for team building, which kicks off a weak hiring process. There are the surface-level desires to build a "world-class team” or make the lists of companies with the best culture. But even seemingly more detailed statements such as "I want a team of focused, hard workers who fundamentally believe in our mission" are still too nebulous.

To go further, Pupius recommends creating a comprehensive definition of the type of person who will succeed at your company specifically. What is unique to your company and your mission? What unique qualities in people will building that type of company require? Ask yourself, will this vision repel people who aren't a good fit? If yes, that means it's not an empty statement. Most importantly, Pupius notes that the vision needs to consider your team as a whole — a single, coherent product.

Just like it doesn't work to build a product as a collection of features, you don't want to build a team that's just a collection of individuals, no matter how exceptional they each are.

At Range, the founding team took a hike together to forge the company’s vision for talent. "I find that physical activity really helps drive creativity, and being outside the office can help everyone look at themselves more objectively," Pupius says. In brutally honest fashion, they listed the traits and qualities that were already on the team, calling out their own and each other's particular strengths and weaknesses. This allowed them to identify what type of people they'd need to complement their shortcomings and extend their capabilities. (For example, they realized that they're largely a band of intuitive introverts who could really benefit from more process-driven extroverts.)

Their resulting hiring vision was not a statement, but a list of traits, values and skills that new recruits should have to succeed at the company, buttress the existing team, and maintain balance. Now, each recruiting process starts with everyone involved reviewing this list so they're reminded that they're responsible for building a well-rounded, smooth-operating whole.

To implement this on your team, document your own vision as a group and think about what rules will get you there. Just as you want to have values, beliefs and guidelines that shape how you achieve your product vision, you need to have hiring principles that will help you make good decisions while eliminating bias. Write down what a standard recruiting process might look like, then ask yourself:

- Where might biases get introduced?

- Where and why might bad decisions get made?

- Where might people on the hiring loop have blind spots?

- Where and how might you fail to unearth qualities that would be awesome for your company to have?

Use your answers to these questions to create and enforce a set of principles that will help you find the people your vision describes. At Medium, for example, Pupius and his team came up with “Provide candidates with several success modes” as one of the principles. In practice, this meant offering technical candidates multiple choices to demonstrate their relevant aptitudes: whiteboarding, a programming exercise, a design exercise, building an app over the course of a couple days and presenting it to the hiring loop, or coming into the office to give a tech talk to junior employees.

Even more tactically, Pupius and his team at Medium sent their hiring rubric to engineering candidates in advance so they would know how they were being evaluated. "People were coming in feeling prepared, like they'd studied for a test rather than dreading a pop quiz," says Pupius. "This totally changed the tenor of conversation and their comfort level. You don't get anything out of people feeling nervous and on edge.”

2. Bring in more candidates by avoiding cliches and doing some (gentle) stalking.

A lack of diversity often stems from the unintentional, inherent bias that lurks within a startup’s recruiting process. As Atlassian’s Global Head of Diversity and Belonging, Aubrey Blanche worked to combat this by standardizing how candidates were interviewed and evaluated, in order to make sure everyone was assessed against the same technical bar.

But even with the right recruiting tools and interview system in place, it’s hard to have an impact if underrepresented candidates aren’t applying to open jobs in the first place. This is something Blanche ran up against at Atlassian. “In 2015, we had put all this work into redesigning our recruiting process for our graduate program and when we opened up the job applications, we received zero female applicants in the first few weeks,” she says. To attract a more a balanced set of candidates, Blanche relied on these three tactics:

Tactic #1: Spell out your commitment to fair hiring practices, avoiding cliches like the plague.

Blanche is an evangelist for Textio, the augmented writing platform that gives real time feedback about both the gender balance as well as the overall impact of job ads. And the tool’s data shows that job listings with strong equal opportunity language fill 10% faster on average across all demographic groups. “Adding an equal employment opportunity (EEO) statement to our job ads both improved the balance of our candidate pipelines as well as actual candidate quality,” says Blanche. “We tend to think of equal opportunity language as an American thing, because it stems from the Civil Rights Act. But what was interesting was that Textio’s data and our experiences have shown that EEO statements work even better outside the U.S. than inside of it.”

However, a perfunctory statement isn’t enough — it actually performs worse than postings with no EEO statement at all. “You have to customize it and call out that it’s a priority, in your brand language. It can literally be as simple as writing ‘We encourage people from underrepresented groups to apply,’ on your job ads. That really works,” says Blanche.

Aside from explicit EEO statements, the impact of language in job descriptions rears its head in other, more subtle ways. Certain words and tired phrases such as “rockstars” or “ninjas” have become embedded in tech jargon, even though they send up major red flags. “Using highly corporate language is often a signal to people of color that they won’t thrive, because that language was developed in predominantly White, male spaces,” Blanche says. “Get rid of it, say what you mean and be specific.” Here are some additional examples of cliches to look out for:

- Drives results. What kind of results? Aggressive, flashy ones or thoughtful, meaningful change?

- Stakeholders or buy-in. If someone is reporting to their stakeholders, who are those stakeholders? Why not “agreement”?

- Work hard, play hard. What if a fantastic applicant has outside responsibilities, or is seeking work-life balance and sustainable impact at your company?

“A big part of this is just being more thoughtful about the word choices you make. There are incredibly subtle language differences,” says Blanche. “For example, when you describe a position as managing a team, you increase the number of male applicants. For developing a team, it increases the number of female applicants. But leading a team is more gender neutral, helping you get the largest, most balanced and most qualified set of applicants for your open role. Of course you’re actually doing all three, but tweaking the message changes the outcomes,” she says.

.jpg)

Tactic #2: Get creative (and do some gentle stalking).

Outside of choosing the right words, Blanche also credits her self-described “weird” sourcing tactics as a secret weapon of sorts. In her role at Atlassian, she actively seeks out underrepresented groups and encourages them to apply.

“I’ve followed hashtags on Twitter that are associated with underrepresented people in tech and I tweet job ads at those participating in them. It sounds weird, but I’m completely serious. I say ‘Hi, you look like a great UX designer and we have these three open roles that you should take a look at,’” she says.“I’ve also gone on Amazon and looked at the technology books, read the reviews and tried to find out who wrote them, because women tend to write more reviews than men do. No one’s going to write a review of a Node.js book unless they know what they’re talking about.”

Tactic #3: Spot skills in non-linear experiences.

When looking at product manager candidates, don’t automatically dismiss those without product management experience. “People don’t have career paths, they have growth paths. We need to get better at thinking for others about what useful skills they’ve gained from unusual, non-linear experiences,” says Blanche. “So at Atlassian, we try to get at those behaviors during the interview process in a way that’s agnostic to your background. Maybe you got your project management skills from a previous role or maybe you got it from coaching and organizing your kid’s soccer team.”

Dive deeper into Blanche’s playbook for stepping up diversity and inclusion efforts to read more of her thoughts on other topics ranging from intersectionality and unconscious bias to data and driving small experiments.

3. Make interviewing a costly team sport.

Every engineering leader spends time on building and rebuilding teams, but while at Clover Health and Yammer, Marco Rogers obsessed on designing and refining an immaculate interview process. It was that craftsmanship that helped him hire over a dozen developers at Yammer, grow the Clover engineering team from one to 50, and start to scale up Lever’s technical team.

We’ve previously highlighted Rogers’ tactic of using three person interviews to reduce bias and elevate the perspective of more junior employees. But what also stands out from his approach is that he’s designed a system that has gotten his technical teams involved — and energized — to interview their future colleagues. To him, interviewing is a team priority: engineers on his team who are seasoned interviewers can conduct 12-16 interviews per month.

This interviewing principle is one that Rogers has seen get pushback. “For some, it’s an issue of scope and something leaders and recruiters should be doing. For others, it comes down to a concern that not everyone can represent the company in an interview. People also say that it’s too costly to have everyone trained and involved,” says Rogers. “But interviewing is a critical business activity. It's going to feel costly — and it should. It's like saying, ‘Hey, we're having engineers write a lot of code. That feels costly.’ That's kind of the thing we need them to do, and that's how I feel about interviewing. I need the team to help me understand if we are bringing on the right people. These are people you’ll be working with every day for years. I think that’s worth a few hours of your time periodically.”

Your entire team should conduct interviews. Everybody. If you don’t want some people to interview, ask yourself why. If you’re worried about how they’re representing the company, there’s a bigger issue at hand.

As the engineering leader, Rogers sees it as his responsibility to develop this skill in his team. “I put myself in a position to evaluate how the engineers on my team are doing in interviews. In the early days, I pair myself with new interviewers in the three-person sessions. In those situations, I’m not only evaluating the candidate, but observe the engineer’s ability to interview,” says Rogers. “When we do a roundup with all the interviewers, I ask each person to reflect back to the group how the sessions went. I can ask more questions, probe and help them unpack what happened. This paves the way to offer feedback and suggest other ways to get through interview challenges.”

The other advantage in having everyone interview is that it’s easier to identify members of the team who are comfortable, confident interviewers — people who the engineering leader can tap to serve as mentors to make less experienced colleagues better interviewers. “I get to know which engineer is skilled with candidates, both from feedback from the roundup, as well as being in the interview with them. For example, I keep notes on who’s good at conducting the technical exercise or a certain series of interview questions that we ask,” says Rogers. “With that context, I have an understanding of interviewers’ strengths and who can help their colleagues improve their interviewing skills as they get more sessions under their belt.”

4. Look for insubordinates and turn candidates into cultural detectives.

In the realm of startups, the initial act of founding a company is an expression of nonconformity. Founders must eventually convince others to join them, internalize that vision and will it into reality. But isn’t it counterintuitive to bring other nonconformists — who may buck their ideas — into the fold?

“Every leader needs followers. We can’t all be nonconformists at every moment, but conformity is dangerous — especially for an entity in formation,” says Adam Grant, bestselling author and professor at Wharton. “For startups, there's so much pivoting that’s required that if you have a bunch of sheep, you’re in bad shape.” That’s why it’s imperative for early-stage companies to recognize and recruit what Grant calls “originals.”

For example, in his research, Grant looked for people who had engaged in very visible acts of nonconformity — the insubordinates. While it’s important to triage troublemakers, you don’t want to miss an original in your midst. “I had a funny conversation with a military general where I asked for a list of people who were most guilty of insubordination,” says Grant. “I said, ‘I want to know who was insubordinate but ended up actually being a great innovator.’ The person that annoyed middle managers but was valued by higher-ups. That led to a lot of really good names and a few crazy people.”

In a startup setting, this may mean rewiring your thinking about those who have been fired. “Take Sarah Robb O'Hagan. She held senior roles at both Virgin and Atari and got fired at both. A deadbeat right? Afterwards, she got a job at Nike and then became the president of Gatorade and Equinox,” says Grant. “When she guest-spoke at my class, she swore six times in the first five minutes. Sara doesn’t worry about pleasing others or fitting in. At Gatorade, she championed many ideas that nobody liked. For one, she said it shouldn’t be just a sports drink, but a sports performance company. Everyone hated those ideas, until they eventually rescued the brand.”

But if you’re a founder or manager building out your team, you may not have a wealth of time or data to suss out originals as Grant did. Furthermore, it can be difficult to see if there’s substance beneath surface indications of nonconformity. Here are two unconventional questions and exercises to help validate an original:

- Uncover their roads not taken. Originals are supremely prolific. The London Philharmonic Orchestra selected the 50 greatest classical music compositions. The list included six pieces from Mozart, five from Beethoven and three from Bach. “To generate those masterpieces, Mozart composed 600 pieces, Beethoven created 650 and Bach produced over a thousand compositions. A broader study showed that the more pieces a composer created over a five-year window, the greater the chances of a hit,” says Grant. “One way to produce great, new ideas is to come up with more of them. But what we surface on resumes and interviews is a filtered set of ideas and interests — and likely those that led to desired outcomes. Ask candidates, ‘What did you try but ultimately give up on — and why?’ Look for those who demonstrate continuous curiosity, but a willingness to move on when the writing’s on the wall.”

- Make the candidate a culture detective. Grant recommends assessing how candidates view your company culture. “Two weeks before her interview, give a candidate three names of colleagues to reach out to learn more about the culture. Tell her that when she comes in, you want to know what’s working and what needs to be changed,” he says. “You can also run this exercise same day if candidates are on site for a half-day or more. You can learn a tremendous amount from the adjustments they suggest, and the questions they ask your colleagues — and you might pick up some useful ideas along the way.”

If you’re five or 500 people, hire as many originals as you can. Yes, there are risks of hiring too many originals — but it’s even riskier to hire too few.

5. Start making reference calls earlier and present your findings back to the candidate.

Recruiting and hiring executives is difficult for any leader, but especially for first-time or early-stage founders who may not have enough knowledge to test candidates for skill in their area of expertise. Thumbtack CEO Marco Zappacosta has been there, and he’s relied on a thorough process for vetting and closing a leadership team to get through it. And one of his best practices for evaluating senior executives centers around references and backchanneling.

What stands out is that he doesn’t wait until the end of the hiring process to get started — and he's not looking for the candidate to flip him a set of names. But even if these unconventional methods don't fit your style, the tailored questions he peppers references with will be valuable additions to your hiring toolkit. Here's a look at the process Zappacosta follows:

After wrapping up the second conversation with a candidate that’s continuing on, Zappacosta gives notice that he’ll start asking people about them in parallel as they move on in the interview process. “There are two important parts to this approach. First, I’m upfront about it and we take care to manage sensitivities with their current employer and a candidate’s timeline. Second, I don’t ask for references,” says Zappacosta. “I tell them that I’ll reach out to various people. The best answer? ‘Awesome. Talk to everybody.’ But many clam up or preface how there are two sides to every story, which of course is true.”

Zappacosta then talks to not two or three references but 10 to 20 people that he draws from various stages of the executive’s career. Historically, he's spent as much time on interviews as he does with references. So if he’s spent 15 hours with a candidate, he’ll spend the same amount of time backchanneling. “You want a holistic view, so you look to talk to peers, managers, and reports from the most important years in their career. I’m looking to learn exactly what they uniquely contributed and how well they worked with others,” he says.

Here are some questions Zappacosta asks that can be applied to your own reference calls more broadly:

- Where did they spike? How did they help create leverage for the business?

- How was this person perceived by others? This is better than asking “What did you think of this person?” because the reference is more likely to be honest, making it easier for the interviewer to audit the answer.

- I’ve talked to three other members of the executive team at this company and they all called out this issue. What’s your read on that? This question gives references permission to be honest about red flags or faults.

- What haven’t I asked that, if you were me, you would want to know about this person? This question gives references free license to say what they’ve wanted to share. This is often a good question to ask in the middle — versus the end — to “unlock” other conversations.

- If this person's on the executive team of a company you're thinking of joining, would that make you more or less excited? This question helps place the reference in the actual hiring decision — and potentially answer more honestly.

The final and most personal part of the executive interview process happens at the end, when Zappacosta presents the good, bad and ugly of the reference calls back to the candidate and goes through each area one by one. “My question for each section is: ‘Why do you think I heard that?’ I’m listening as much for the answer as I am for how the candidate responds,” says Zappacosta. “Are they defensive and try to explain away the observation? Or do they say something like, ‘This is what I've been working on for a long time. I'm not a natural public speaker. I’m more comfortable in small groups, but I’m taking a more active role in All Hands and I've signed up for a few conferences.’”

Sure, I backchannel to confirm candidates’ skills. And I want the exec’s take, too. But most of all, I want to know how comfortable they are stepping in front of the mirror.

6. Court, dazzle and close by focusing on the details and always going out of your way.

Toward the end of her interview process with NerdWallet, Flo Thinh Chialtas politely accepted a dinner invitation from its CEO, Tim Chen. But instead of getting Korean food with him, Chen said another person, Dan Yoo, would be joining her. The three-hour feast of Chialtas’ favorite food was as top-notch as the company. Yoo asked about her career and interests, all the while promoting NerdWallet. At one point, Chialtas was sold and said she could see herself working at NerdWallet and with Yoo, to which he replied: “Oh, yeah, but I haven’t signed yet.”

The lightbulb went off. Yoo was not NerdWallet’s COO (as she had first thought), but its final candidate — and Chen had paired the two so they’d bond and hopefully sign together. They did. “If I could sum up my hiring experience, I would say it was extremely authentic,” says Chialtas. “Tim shepherded me the entire way. If he was trying to close me, he did a hell of a job.” Since that magical moment, Chialtas has spent her days at NerdWallet designing and refining a dazzling experience that closes candidates.

For the startup looking to do the same, try out her tactic of signalling dedication through details. For example, the NerdWallet team looks for small nuances in candidates’ social media profiles, such as their favorite food or sports team, to weave into their outbound messages and future communication. “We try to find as many touch points as we can to connect on a personal level. Investing in this early makes closing conversations drastically easier because you’re acknowledging someone as a person — not just a name on a hiring list — from the start,” Chialtas says.

Paying attention to the details also applies to the logistical side of the candidate journey, where little gestures can make a big impact. For example, NerdWallet gives candidates the following materials to make their experience before and after company onsites better:

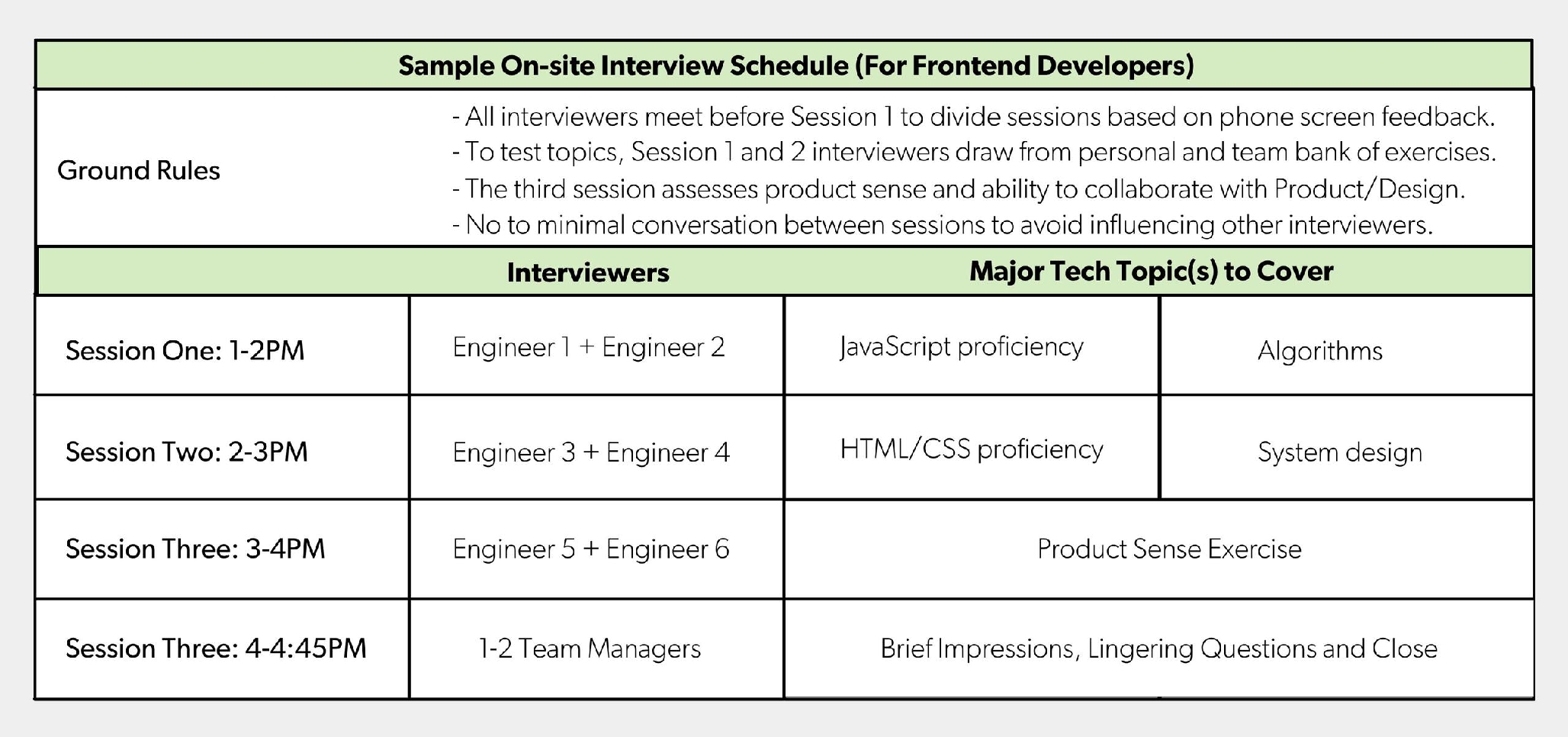

- An interview day outline. NerdWallet sends every candidate an outline detailing their day at the office 48-hours before they arrive. It includes: the names and roles of the team members with whom they'll meet, interview times and duration, and any activities they will be participating in throughout the day. The goal is to provide them with all of the information they'll need to be excited to come in and have a great experience.

- Transportation tips. To help people avoid feeling frazzled walking into their interview, NerdWallet provides transportation tips, such as the nearest bus stops and parking spots, so candidates can start their day on a positive note.

- Literature for loved ones. Before a candidate receives an offer, NerdWallet shares their Benefits Summary. “It’s a helpful guide for people to take home to their families, and say, ‘Hey, I’m considering this offer. Let’s look through this together,’” says Chialtas.

But if she could give only one piece of advice about recruiting, it would be to always go out of your way. Over her almost two decades in recruiting, Chialtas believes what’s changed most about the landscape is the increasing importance of getting out in front of candidates to successfully court talent, especially when they aren’t actively looking for a new role. “You can’t win unless you invest in candidates’ experiences. It has to become second nature,” she says.

As an example of that philosophy in action, Chialtas recalls a particular search where she was the third recruiter brought in to try to tackle a challenging open role. “It wasn’t going well, and the hiring manager was getting really impatient. I found a candidate, reviewed his resume and felt like everything was in sync. I gave him a call in the morning and, as he spoke, I kept thinking, ‘This is him. This is the candidate,’” she says. “We knew the next step and timeline, but I felt it wasn’t enough. So I asked him: ‘What are you doing in a couple of hours? Can I come down your way and meet you for lunch?’ It was bold but it’s an example of the ripple effects of going out of your way. The guy ended up getting a job there and staying a couple of years at the company.”

Chialtas continues: “Similar to getting married or buying a house, finding a new job is really stressful. So, whenever you think you’re done honing your hiring process, return to it and ask yourself: how can I alleviate stress for the candidate and make the process more frictionless? The future of your team depends on it.”

This is just the beginning of the Review's wisdom on tapping into unconventional tactics that can inspire and uplevel your hiring process. Check out the full articles referenced above as well as others on scaling hiring traditions, building engineering teams and running a perfect sales hiring process.

Image by Filograph / Getty Images.