Big ideas, strong-willed characters, impossible deadlines and close quarters — if you wrote out a recipe for conflict, it might bear an uncanny resemblance to the high-stakes, pressure-cooker environment of a startup.

Of course, any situation where people come together to solve tough problems will inevitably give rise to disagreement. The key to sustainable innovation is making sure that disagreement is productive rather than inhibitive, paving a path forward instead of placing self-imposed roadblocks on progress. And in the emotionally-intense setting of a startup, it’s all the more important to take care that the embers of conflict don’t grow into an unmanageable conflagration.

Over the years, we’ve spoken with operators who’ve weathered the trials of startup life and emerged with a wisened perspective on conflict. As we sifted through their advice on the thornier moments of startup life, a clear theme emerged: The most effective conflict resolution tactics are put in place before conflict strikes. Laying the groundwork begins with the conscious creation of an environment where folks feel that their input is respected, and where leaders set an example for empathetic and levelheaded communication.

The six tactics that follow come from top engineers, seasoned managers and experts in human behavior. For founders knee-deep in disharmony, they offer tactics for immediate conflict mediation and management. They also dive into the strategies leaders can use to nip discord in the bud, from addressing performance proactively to making conflict resolution a cornerstone of company culture.

After all, if you wouldn’t ignore critical bugs in your code, you shouldn’t turn a blind eye to buggy human dynamics, either. And not just because it’s the right thing to do (which it is), but because team dysfunction poses an existential threat to a company. When teams can engage with a diversity of ideas, a product is stronger, and work is simply a better place to be.

1. Follow the A-E-I-O-U model for mindful conflict management.

When conflict arises in the workplace, people have two tendencies: Either they’ll hide from discomfort and hope the issue dissipate, or they’ll address the conflict head-on, often without filtering the words they use. Neither response is correct, nor constructive. Avoiding problems only allows them to fester and impact more people, while hasty, non-strategic communication can turn a small fire into a blaze.

Enter executive coaches Ann Mehl and Jerry Colonna. Through years of training senior execs at Kickstarter, Etsy and SoundCloud during the thorniest moments of company-building, they’ve developed concrete tactics for practicing nonviolent communication, a model that emphasizes awareness, responsibility and empathy.

To help clients communicate through confrontations mindfully, Mehl recommends the A-E-I-O-U Model of Managing Conflict. It’s distinguished from other strategies by assuming that both sides of any argument mean well — basically, that there are positive reasons behind each person’s actions.

There's no such thing as a conflict-free environment, so you better learn how to deal with it.

Standing for Acknowledge, Express, Identify, Outcome, and Understanding, the A-E-I-O-U method can be used to resolve a variety of standoffs: employee-to-boss, peer-to-peer, co-founder to co-founder. It’s particularly useful for early startups, Mehl says, because everyone knows each other and is learning together. No matter how old your company is or how it’s structured, employees should always feel comfortable approaching managers and communicating on a level playing field.

In any conflict situation, finding a solution to the problem at hand is the highest goal. To do that, you must separate the person you’re in conflict with from that problem.

Mehl advises preparing constructive statements ahead of time before heading into any confrontational discussion. Doing this will help you stay focused and minimize incoherent or incomplete explanations. Preparing also sends the signal that you're invested in doing the right thing. It demonstrates good will.

- ACKNOWLEDGE: See the positive intentions. Assume the other person in the argument means well. Try to understanding his or her rationale and state it out loud directly to them. Announce that you know that they are trying to do something good, and that you do have a grasp on why they are doing what they’re doing.

- EXPRESS: Articulate what you see. Affirm the positive intention you’ve identified and express your own specific concern. Use statements that make it clear that your words are your own: “I think/I feel.” If you’re mediating a conflict, invite each side to take a few minutes to clarify their precise worries or issues.

- IDENTIFY: Propose a solution. Clearly define your objectives and recommendations. What’s the outcome you want to achieve? Non-defensively propose changes you’d like to see occur using the phrasing, “I would like…” as opposed to “I want…” You should try to build consensus by demonstrating how your solution will resolve everyone’s concerns, not just your own.

- OUTCOME: Outline the benefits. What’s in it for your opposition if they agree to accommodate you? People respond much more positively when they can buy into the reason for changing their actions or behavior. What are the advantages of your proposal? Don’t forget one of the most powerful motivators is simple recognition (i.e. “Thanks, I appreciate your flexibility on this issue,” or “I owe you one”). This can go a long way toward establishing harmony.

- UNDERSTANDING: Ask for feedback. Either nail down agreement on a next action or step, or work together to develop alternatives. Asking something like, “Can we agree to try this for a little while to see if it works for both of us?” gives the other person the option to accept your proposal without admitting defeat.

Throughout the A-E-I-O-U process, it’s critical that you maintain an environment conducive to resolution. Keeping calm is the top priority. Clarify misunderstandings in real time by applying active listening skills. Continue to rephrase things to ensure crystal clear understanding: “What I hear you saying is…” “Am I correct in thinking that your biggest concern is…?” This way, there won’t be room for doubt about people’s goals and intentions, and it gives each party a chance to clarify and speak their mind.

It's like a game of tennis— the longer you keep the ball in play, the more you learn from each other.

And, just as tennis players are happy winning best out of three or five sets, colleagues may need to go multiple rounds before a solution is reached. You shouldn’t expect to resolve situations in a day, Mehl says. Both she and Colonna have encountered co-founders who were barely able to talk to each other. Applying the A-E-I-O-U method gave them a reason to talk, and eventually transitioned into healthy, regular communication.

2. Nip the Narcissus at the bud — and beware the Bean Counter.

University of Pennsylvania Clinical Professor of Psychiatry Dr. Jody Foster has seen her fair share of pot-stirrers and bulls-in-the-china-shop. Drawing from her research at the intersection of business and psychiatry, and her book The Schmuck in My Office, she categorizes the type of people whom others find difficult at work, and shares how companies can monitor for and manage them. She specifically hones in on two archetypes that most commonly plague early-stage companies: The Narcissus and the Bean Counter.

The Narcissus

This profile can be both the engine and the noose for many startups. “Many of us who help build companies fit this profile — myself included — and you’ll definitely work with one. After all, it isn’t wrong to have some narcissism. I mean if we didn't have a bit of extra self-belief, it’s hard to rise to the challenge to get to where we want to go,” says Foster. “But when an inflated ego, self-praise and condescension take over, it can become a problem quickly. The Narcissus is initially very charismatic, inspiring people to follow him. There’s a lot of belief in the Narcissus and his ability to come through with everything they promise, but there’s often disappointment.”

Here are other signs or attributes of a Narcissus:

- Is “the best” or knows “the most”

- Fishes for compliments

- Talks to hear himself talk

- Name drops

- Takes credit for others’ work

- “My way or the highway” attitude

- Is sensitive to rejection

The Narcissus leans toward monologues (over dialogues), often finds worth in pedigree (over purpose) and demands mind-reading (rather than communicating so he’s understood). “I once knew a manager in a mechanical engineering firm. He was working on a model with his team and he asked one of his associates for a knife to make an adjustment,” says Foster. “She handed him the wrong knife because she couldn't read his mind as to the exact knife that he wanted. As a result, he went ballistic, screaming expletives and kicking things. While it was he who should have felt humiliated, she felt embarrassed in front of her peers.”

So what’s going on with the Narcissus — and why does he do these things? “Narcissism is a personality of dichotomies. What we see may be an aggressive, self-propagating person. But what we're not seeing is that this presentation is hiding deeply low self-esteem,” says Foster. “Think of the actual size of Narcissus' ego as a peanut. It’s fragile and easy to crush. To protect it, Narcissus takes that little peanut, drops it in a balloon and blows that balloon up as big possible to create a ‘decoy ego.’ He fills the room with himself and keeps everybody away from that peanut at all costs. What I love about this analogy is that balloons are inherently fragile. One pop and it's immediately right sized. And that's what’s happening with Narcissus.”

For those who work with a Narcissus, keep in mind this balloon imagery. “Always keep in your mind that Narcissus is keeping that balloon full. It's a very hard way to live, getting that balloon puffed up and guarding it all the time,” says Foster. “We can try to have a little empathy for what she has to go through. Find opportunities to be kind and to give her some positive feedback in the context of the collective, such as a team or company. You may then start to see that Narcissus is going to be able to relax a little and realize, ‘Oh, this person isn't out to get me or pop my balloon.’”

Here are tactical ways that you rephrase some comments to the Narcissus to get a better response and develop a healthier working relationship:

Don’t say: “You look really stressed right now. Are you worried you aren’t going to do a good job or something?”

Do say: “We’re all stressed about this upcoming deadline. I know I’m a bit on edge about how I’ll do.”

Don’t say: “Don’t cut me down in public just to make yourself look better.”

Do say: “I understand that you disagreed with my approach today, and I respect your perspective, but correcting me publicly in front of all my coworkers made me feel very embarrassed.”

Don’t say: “It was rude of you to insult Alex at the staff meeting.”

Do say: “Imagine how Alex felt when you call him stupid. Imagine if someone called you stupid.”

Don’t say: “Can you get me that draft of the proposal by Friday?”

Do say: “I can’t wait to see your draft of the proposal on Friday.”

Don’t say: “I don’t care how good you are at your job; your behavior is unacceptable and obviously something is wrong with you. You need therapy.”

Do say: “I really think you could be a CEO one day, but I worry that this one thing you do makes people feel bad and gets in your way. Maybe a coach could help you achieve your full potential.”

Bean Counter

At the root of the Bean Counter’s personality is obsession, a thought or impulse that dominates one’s mind. For this profile, it manifests as holding on to every detail and a tendency to be organized in a particular way — even if not helpful to others. Often their extraordinary effort to hang on, gather and sort interferes with their productivity — and that of the teams around them.

Here are other signs or attributes of the Bean Counter:

- Is inflexible and closed-minded

- Has difficulty making decisions and being efficient

- Gets “stuck in the weeds” and “can’t see the forest through the trees”

- Micromanages others

- Hangs onto details and wants them organized in a very particular way

- Preoccupied with orderliness and control

“I knew a Chief Operating Officer who treated every penny in the company coffers as if it were her own money. She’d hire accountants to look into an $8 discrepancy in a multi-million dollar budget,” says Foster. “She was very rigid with her process and only she could execute it. When she delegated, she was really just controlling the work from a distance. If a team presented a proposal that showed a strong return on investment, she’d shoot it down outright if it required even a dollar of company funds.”

Eventually, the COO’s inflexible behavior eroded profits and a newly appointed CEO fired her. “The COO had shown intense commitment, arriving early and leaving late — but spent her day doing tasks like color-coding binders of company documents and materials. What was amazing was what they discovered in her absence,” says Foster. “After her departure, her tasks were assigned to other administrators. What took the former COO hours now took a matter of minutes. But all the work had zero yield. She was so stuck in the weeds by what she thought was critical that responsibilities of the rest of the company fell by the wayside. Managers of those goals were frustrated because they were doing her work and not able to do their projects.”

If you work with a Bean Counter, what can help you better connect and cooperate with her? “Just as the Narcissus is trying to mask his insecurity, the Bean Counter is trying to hide her fear of losing control of herself or her environment. The Bean Counter wants to overlay laws and rules on the vicissitudes of life, but she knows she really can't do that. So she digs in her heels on what she thinks she can control,” says Foster. “If you’re the boss of a Bean Counter, when he makes mistakes, normalize them. Tell him it's not Armageddon. Direct him toward detail-oriented activities with deadlines and directions. If you working for or with a Bean Counter, don’t challenge his controlling nature. Tell him you admire his dedication — and let him know that you're dedicated too. Don't promise more than you can deliver. When you make a mistake, own it. Don't rationalize or be defensive.”

Try some of these rephrased responses to better resonate with a Bean Counter:

Don’t say: “You’re so controlling, just let go of it!”

Do say: “I’m so impressed with your dedication. I feel the same way about my work, so you can rely on me.”

Don’t say: “Yeah, there are a few mistakes but what’s the big deal? This isn’t really important stuff.”

Do say: “You’re right, I did overlook several items and I made some mistakes. I’ll correct this now and I’ll definitely pay more attention next time.”

Don’t say: “No, I disagree with you, I think it’s fine as is.”

Do say: “Here is my corrected work. I’ve noted where you made suggestions and highlighted my associated changes.”

Don’t say: “What do you mean I’m not getting my reimbursement?”

Do say: “I understand that we need to tighten our belts but I was unfortunately counting on this particular reimbursement. Do you think we could discuss a compromise?”

There’s a fine line between being detail-oriented and detail-saturated. It’s the difference between details giving direction and details impeding decisions.

Read more about Dr. Foster’s detailed taxonomy of troublemakers in the workplace.

3. Do go to bed angry, but don’t let your grump spiral spin out of control.

Most of us have had those days: You and your manager just can’t agree. You and your team are locking horns. When conflict at work seems irresolvable, and negative emotions are boiling over, you might think that your only option is to quit immediately and slam the door on the way out. But don’t rage-quit just yet — there’s another way through it.

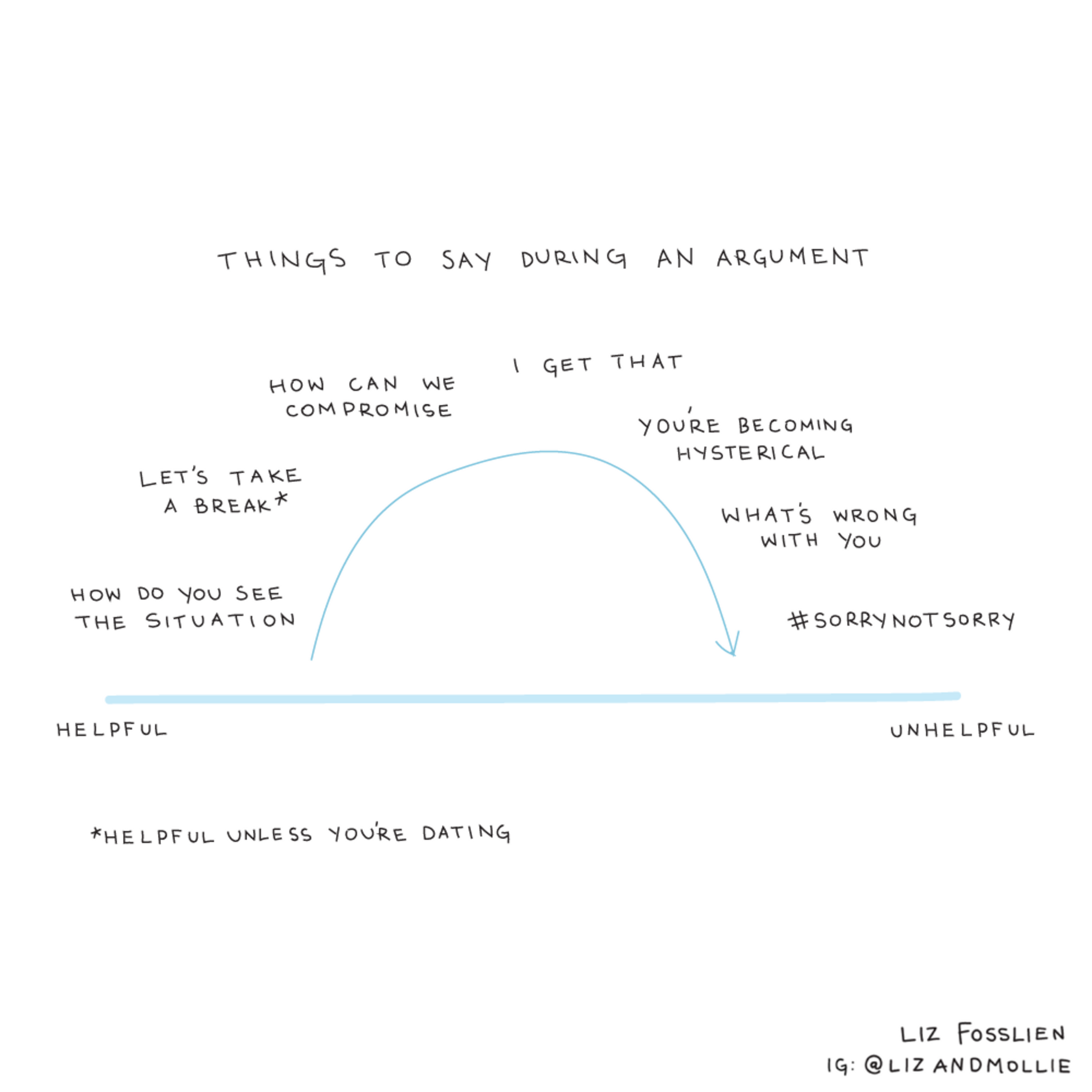

“We don’t often slow down and spend time on relationships in intense startups environments, so conflict becomes magnified,” says Liz Fosslien, Head of Content at Humu. She’s also the author and illustrator of No Hard Feelings: The Secret Power of Embracing Emotions at Work. “If we take the time to form relationships and better understand each other’s work styles, we can avoid a lot of misunderstanding and grief.”

If your startup’s task is to grow and scale and make your product the best it can be, why wouldn’t you apply that same urgency to investing in good relationships at work?

You shouldn’t suppress or ignore your emotions, but you also don’t want to be a feelings firehose. “Startup settings are the most volatile when it comes to confronting conflict,” says Fosslien.

“My co-author Mollie and I hate the advice ‘never go to bed angry.’ Go to bed angry! Negative emotions, like jealousy or frustration, skew your view on reality,” says Fosslien. "If you know you’re going to have a difficult conversation, take a five-minute walk beforehand. You might think you’re too busy, but those minutes aren’t going to make or break your company — a public outburst, however, could have far-reaching consequences.”

Sometimes, conflict arises out of another form of negative emotion. You probably recognize them: those tiny irritations that, left unchecked, can fester and infect relationships. Fosslien calls them “grump spirals” — and they are, unfortunately, contagious.

“If you catch yourself thinking these extreme words, like always, never, catastrophe, it’s usually an indication that you’re stuck in a negative thought spiral that’s making you blow a situation out of proportion,” she says.

In their book, Fosslien and Duffy created a step-by-step guide to untangling yourself from a spiral, using the example of what to do when one of your team members suggests a big change right before a deadline

- Notice difficult emotions. Instead of snapping at your coworker in annoyance, pause and observe the feeling.

- Label each emotion. The ability to describe complex feelings, to distinguish awesome from happy, content, or thrilled, is called emotional granularity. Emotional granularity is linked with better emotional regulation and a lower likelihood to become vindictive when stressed. With emotional granularity on the team project, you’ll be able to realize that by “I’m feeling annoyed,” you really mean “I’m worried that we won’t have time to make these changes.”

- Understand the need behind each emotion. Once you’ve labeled each emotion, flip your perspective and explicitly state what you’d like to be feeling instead. Ask yourself “What do I want to feel?” If you’d like to feel calm instead of anxious, figure out what you need to do to successfully relax. That might be ensuring stability: you want the project to stay on track.

- Express your needs. Don’t say, “I’m annoyed by this request for last-minute changes.” Try, “Your edits are good, but because we are down to the wire, stability and predictability are important. What edits do we have time for? How can we make this work?”

4. Managers, here’s why you need to fight as if you’re right, but listen as if you’re wrong.

Managers play an instrumental role in setting a culture of productive confrontation. Robert Sutton, management expert at Stanford's School of Engineering and author of The No Asshole Rule, has observed that leaders experience a “magnification effect”: When you’re given a leadership position, everyone suddenly starts watching what you do very closely. The skill that every great boss should strive to cultivate, then, is perceptiveness — to dynamic of the company, as well as sensitivity to how one’s own actions cause intended and unintended ripple effects through teams.

This is a particularly key insight for managing conflict. Sutton offers managers a way to lead with perceptiveness, striking a balance between leading authoritatively and listening to people on their level. He quotes American organizational theorist Karl Weick:

Fight as if you're right. Listen as if you're wrong.

“There's a lot of evidence, especially for creative work, that the most effective teams fight in an atmosphere of mutual respect,” Sutton says. He cites the example of Brad Bird, the Pixar director who brought The Incredibles and Ratatouille to life, was famous for creating constructive conflict. But Pixar wanted to shake things up, so they gave him a chance and his own team. When recruiting, Sutton says Bird asked for all the black sheep. “Give me all the people who are ready to leave — the ones who have new ways to solve problems and are desperate to try them,” he said. The crew drove each other nuts fighting, but in what everyone described as a “loving” atmosphere rooted in respect for each other’s work.

As a boss, crafting this atmosphere is vital. Your goals should evolve over time: Early on, you need to contain fights and encourage free idea generation. “Don’t start shooting things down until you have enough choices,” Sutton says.

Then, when things are finally being decided, you need to convince people to accept defeat gracefully so they can work to implement ideas they disagreed with. “As Andy Grove argued, if you disagree with an idea, you should work especially hard to implement it. That way, when it fails, you know it was because it was a bad idea, not a bad implementation.” Conveying these ideas to your team can have real impact.

5. Take action before you pull out the PIP.

At a startup, conflict comes in many shapes and sizes: minor, differences of opinion, heated squabbles that blow up and blow over. But the worst conflict, and the hardest one to resolve, is the one you’ve let fester.

We’re talking about the long-overdue performance conversation. While performance reviews aren’t necessarily antagonistic in nature (and can actually be impactful opportunities to boost a report’s growth), when confrontation is avoided altogether until managers have no choice but to fire someone, trouble can boil and spill over into a true conflict.

Michael Lopp, VP of Product Engineering at Slack, former leader at Apple and Palantir, and a prolific blogger (known to the tech world as Rands), is here to help managers avoid that. He specializes in identifying and navigating conversations with the sub-par performers of the startup world — the “Jeffs of the world,” as he called them at a First Round CTO Summit several years ago. They’re the ones who aren’t doing anything blatantly wrong, but are just off. They’re less productive, not a culture fit, kind of a jerk and on top of that, they’re costing you more time and money the longer they stay on — whether they’re named Jeff or not. And while there’s no painless approach to performance interventions or letting people go, there is a way to go about it that dodges lawsuits, permanent scars, and (ideally) firing anyone.

“If you’re lying awake at night thinking, ‘God, Jeff is pissing me off,’ your chance at a low-cost solution probably came about three months ago,” says Lopp. “You had the chance to improve things but you sat and waited until it actually started to hurt." The ideal time to act is well before someone becomes a Jeff. And that means implementing programming before you need a PIP.

A quick refresher: PIP is one of the worst and most-feared acronyms out there. Standing for “performance improvement plan,” a PIP usually takes the form of an official, written agreement drafted and overseen by HR that outlines exactly how an employee needs to very quickly get better at their job in order to keep it. They may be more common at large corporations than startups, but even new companies should be familiar with PIP principles to keep their staff on track, especially as they enter rapid growth. Lopp recognizes the need, but hates how they’re used: too often as a last-ditch, half-hearted effort to save someone’s job.

“There are two problems with how PIPs are used. First is that you should want to fix something as soon as you see it go wrong, not at the very end of a long, slow decline. And second, you can’t just throw a switch and fix everything. There isn’t just one or even a couple things you can do to make Jeff better. It’s not just one conversation. It’s a lot of little things that need to be addressed over months, every day, every hour.”

If you’re thinking about putting someone on a PIP, your first question should be what could you have done earlier?

There’s a reason most people are surprised when their manager asks them to go on a performance improvement plan. Of course, people are biased toward denial and against confrontation. But even if they suspected something was wrong, it’s likely no one articulated it to them in a way that they understood and agreed to fix.

To diffuse the confusion and blowups before they happen, Lopp recommends deploying what he calls a pre-PIP — essentially an agreement made between a manager and employee to improve performance without signing anything with an unspoken “or else” at the end of it. This is even easier to implement at a startup that doesn’t have a formal PIP process. Here’s what the pre-PIP route looks like:

- Feedback needs to be immediate. As soon as someone steps off the path or veers into dangerous territory, let them know. “Ideally during the first 90 days, give people an exorbitant amount of feedback,” Lopp says. “Just think, you could have fixed it six or nine months earlier by pulling Jeff aside and saying, hey you really frustrated people in that last meeting because you weren’t listening.”

- Aim for specificity and clarity. Give granular examples of the mistake Jeff is making and how things would look different if he changed his behavior. When you tell Jeff that something is wrong, have him repeat it back to you until what he’s saying matches what you mean. Too often people fall short of expectations because they misunderstand what is expected of them.

- Take the threat out of it. One of the worst things about performance improvement plans is that they’re surrounded by an air of doom. This causes people to either push back and have a bad attitude, or feel hopeless and unable to put in their best effort. Communicate that this isn’t a do-or-die situation.

- Write things down. Even though this isn’t an official PIP filed with HR, it should be quantified and codified. “You should write a well-defined list of things that you can measure. Jeff should be able to see for himself that he is succeeding. You should be able to see the changes that result from this process.” Even if there’s something subjective Jeff should improve, try to put something quantifiable around it.

- Be patient. “Changing behavior is a lot of work. A lot of people assume it’s impossible. But by investing in feedback and giving your leads the ability to have hard conversations, you can do it, and it's often worth it.”

- End with the positives. Always transition the conversation from critical feedback to possible solutions. People naturally cling to the negative, so ending on a positive note could make the difference between motivating Jeff and compelling him to give up.

6. Make conflict cleanup a proactive habit, not a reaction.

Of course, you can never fully avoid conflict — nor would you want to, since conflict often generates new ideas and new ways of thinking. One way to keep conflict productive, rather than corrosive, is making sure that you’re practicing good emotional hygiene every day.

Too often, executive coach Laura Gates hears that clients make the excuse that they don’t have time to tackle interpersonal issues. But the truth is, you don’t have time not to. “The consequences of not identifying and addressing conflicts and corrosive team dynamics are always dire,” she says.

When leaders are unwilling or unable to talk about tough issues, co-founders fight, high performers quit, equally talented people get fired unfairly, projects fall apart or miss deadlines, cultures turn toxic, morale suffers, people leave, and companies implode.

Gates recommends making time for an emotional clearing-out once or twice a year during team retreats. But while one- or two-day facilitated retreats are the ideal setting to dive deep into the interpersonal issues and dynamics holding your team back, you shouldn't have to wait for an annual event to resolve conflict. After all, immediate feedback is most resonant.

Here's how Gates recommends increasing the cadence of emotional cleanup on the job:

Quarterly Management Retreats

It's vital for leaders across your team or company to get along. Erosion of those relationships has far more damaging consequences. Once a quarter, take a day as a retreat just for managers. Split it in half, and make the first half about emotional cleanup and the second about strategic planning and the work ahead.

1:1s

Even though weekly one-on-one meetings tend to be shorter and more tactical, you can reserve half the time for emotional cleanup if it’s necessary (or perhaps one meeting per month). Managers need to play the proactive role here, accepting that reports may have a hard time surfacing issues for a variety of reasons.

Do your best to play facilitator outside of these meetings, noticing the tone and body language of your reports around the office and when they're working together. Make note of anything that suggests tension, distrust, or conflict. Bring that up in your one-on-one next time.

Managers should get vulnerable to start these sessions off. Talk about a past conflict that you think might mirror the one your report is experiencing. If you think your report's issue is with you, try to pinpoint what it's about and relay your vulnerable anecdote about why you may behave or act that way. Give them context. Trace issues back to their roots, rewind and replay, and then establish future alternatives.

Most importantly, make it clear to your reports that what they share with you will be received without judgment and won't go any further. Make a distinction between venting and gossiping (venting serves a purpose to release negative energy and seek resolution) and let them vent without changing your opinion of them or anyone they mention. Keep these promises. If you do all this on a regular basis, you'll keep negative emotions from festering, and nip demoralizing gossip in the bud.

Post-Mortems

Add an interpersonal dynamics segment to every project post-mortem as a team health check-in. Make it a habit to talk openly about any negative behavior, infighting, tensions, or problems that popped up during the course of the project. Figure out where these issues stemmed from and how, in the future, they can be avoided. Document these findings somewhere you'll look before initiating a new project with the same team. "Generally, you want to ask, 'How did we all work together on this? How could it have been better?'" If you do this religiously each time, you get to know and trust each other more, and become increasingly efficient.

Company Values

Lastly, if you have a central set of company-wide values or operating principles for your company, use them as an opportunity to condition everyone toward emotional cleanup. Establish that people should be brave enough to be transparent about how they feel and how they'd like to work with others, that you should invest the time to resolve problems between people, that it's okay to bring your whole emotional self to work, and that feedback should fuel continual improvement. How can you bake those beliefs into these core tenets everyone holds dear? It's worth it.

There’s a lot more wisdom on preventing and navigating conflict where these came from, such as these painstakingly developed questions that will help you approach even the thorniest workplace conversations with empathy and insight and these hard-earned tips on how to detect and debug troublemakers.

Image by bbostjan / iStock / Getty Images Plus.