Over the years, we’ve dug into some complex topics, from technical infrastructure to growth equations. We’ve even covered complexity itself. But there’s one concept that’s familiar yet remains a challenge to parse and make tactical: trust.

It’s intangible, but foundational to nearly every part of company-building. Teams must have conviction in their leaders — and vice versa. Customers need to trust products. Founders seek out advisors and investors who they’re confident will help them build for the long haul.

From the Review’s vantage point, trust surfaces in nearly every interview we do. Inevitably, whether the subject is talking about management practices, go-to-market strategy, customer service, or sales cycles, we hear some version of the refrain: “It all comes down to trust.”

All too often, that’s where people tend to stop. This article spotlights those who kept on, dug deeper to put teeth on the topic of trust, and shared how it can be built, not just assert that it must exist. This roundup offers frameworks, equations and habits that leaders have tested and actually used to create and cultivate trust on their teams.

Read on for specific ways to quickly build confidence and conviction in others, especially as they evolve from stranger to candidate, and from new hire to colleague. We hope you find these tactics immediately actionable — and trust you’ll give them a try.

The ability to quickly establish and then nurture trust over years is a vital yet often overlooked ingredient for success.

1. Leave a good last impression.

Partner Chris Fralic is responsible for First Round Capital’s investments in Warby Parker, Roblox, HotelTonight and Adaptly among others. When asked what’s made his career possible, he’ll tell you outright it’s the relationships — cultivated and built deliberately over many years. Known for helping launch the famed TEDTalks, and a landmark Forbes piece on nailing email introductions, Fralic still responds thoughtfully to over 10,000 emails every year.

At the heart of this ability to connect, is his ability to engender trust even with those who he might have limited context or history. That’s a crucial skill because, at some point, every person is an unknown entity before becoming a trusted colleague on a team.

He asserts that how you exit conversations with new people ultimately lays the groundwork for trusting relationships to be built, not just a transactional exchange to occur. His tactic? End every meeting or conversation with the feeling and optimism you’d like to have at the start of your next conversation with the person.

“Assume you’re going to run into everyone again — it usually happens either by plan or happenstance,” says Fralic. “There are no closed connections. The world is too small.” When you do meet again, you want the person to think, ‘Oh great, it’s so-and-so!’ not ‘I guess I’ll get through this somehow.’ If you envision running into this person again and how you want that to go, it’ll undoubtedly influence how you navigate a present conversation — usually for the better.

For example, Fralic is always impressed by founders who — when turned down — send some variation of, “Thanks for looking even if it’s not a fit. If you have other ideas for us or if anything changes, please let me know,” or, “Chris, when we met, you had a question/issue about X. I just wanted to show you what we’ve done about it — no need to respond.” “A person who says that shows she’s savvy enough to not take bad news personally, or create obligation or awkwardness, or continue to argue their point after you’ve said no. I’ll remember her for it,” he says.

There's time beyond this fundraise and even this company. Relationships take years to build. Start now.

2. Give your most recent performance review to your final round candidates.

Thumbtack CEO and Co-founder Marco Zappacosta has changed how consumers connect to local professionals, with millions of projects completed across the United States since the company started in 2008.

One of his proudest accomplishments, however, was not an innovation, but a realization — one that took nine years to fulfill to his satisfaction. “We've recruited heads of engineering, product, marketplace, finance, HR, operations, marketing and general counsel. For the first time in our history, we've filled all the seats. They're incredible in their own ways and work well together,” says Zappacosta. “It took a bit, but I’ve learned to leave reinvention to our product, not its guardians. I’ve realized how immensely valuable it is to have an experienced executive team.”

In his Review article, Zappacosta thoroughly outlines his process for vetting and closing some of the most important and influential people in his company. One of his best practices is an exchange that occurs at the end of his executive interview process, but is a compelling gesture of vulnerability and trust with any potential hire at an organization.

To put candidates more at ease — and make the evaluation bi-directional — Zappacosta offers his latest 360° review. “One of the last things I do is I share my most recent 360. I give the person a copy so they can see where I hit the mark and what I’m working on. It’s a gesture of my willingness to be completely open. I tell them to ask any question,” says Zappacosta. “For example, one thing that I bring up if they don’t is how I've always gotten feedback that I need to give more praise and recognition. I don't do enough of that. I’m working to make that better, but an executive shouldn't be surprised by it later. And, more so, those who know they need words of affirmation to be productive and happy may take note and speak up.”

After answering any questions, Zappacosta makes an request of his own. “Then I ask them what their current team says about them. It can catch people off guard and make them uncomfortable, but no one has said no. It really gets to their self-awareness and ability to be vulnerable,” he says. “We all have strengths and weaknesses. At this stage of the process, the truth is that we’re stepping into a reality of what it would look like working together. So it’s critical that we can share and exchange at this level.”

Even the most talented people have gaps. That’s why I share my 360 with executive candidates — and ask them to reciprocate.

3. Don’t miss the Day One opportunity.

Before getting into tech, Carly Guthrie managed HR for the Thomas Keller Restaurant Group, owner of elite California restaurant The French Laundry — and their success is no secret. “They are incredibly, incredibly thoughtful about every detail of a guest's dining experience,” she says. “Ahead of time, they'll have already considered food allergies and preferences, even menu items you might have tried previously. It’s a level of care and attention that often gets lost in modern times, but it goes a really long way toward making things special, memorable.”

For decades, Guthrie has helped onboard new employees in both startup offices and crowded restaurants, so she’s got a keen eye to the transition — and opportunity — when a person goes from candidate to new hire. “From a sheer tactical standpoint, you’re never going to have the same opportunity to impact people that you do on their first day,” says Guthrie. “Everyone’s feeling great and psyched to be there, they’re willing to sign their lives away. You have to be organized enough to make them feel even more awesome and reaffirm their choices.”

Set your startup apart by making onboarding extend the excitement from signed offer letter to the first moment someone has as an employee. Start to build trust and psychological safety by making this inflection point seamless. “Create an experience where someone walks in on their first day and everyone is already expecting them. Everyone already knows their name and what they're there to do. Everyone is super welcoming and understanding of the fact that meeting so many new people is overwhelming,” says Guthrie. “Don’t make them wonder where and how they’ll eat lunch. Remove all of those small obstacles that cause first-day nerves. All of this shows a level of thoughtfulness that many organizations fail to accomplish.”

You don’t have to have all of the answers about your culture, or even what a new hire can expect down the line, she says. But by showing up and being willing to think through and act on the small things, you distinguish yourself and build trust.

Here are few onboarding rules for managers:

- Rule #1: Never have someone start their first day at 9 a.m.— have them come at 11. “That gives you a chance to get in, have your coffee, get through your email, and doublecheck that everything is set up for them to arrive,” she says. “By the time it's 11 a.m., you can give them your full attention, help them get the paperwork out of the way, and introduce them to the team.”

- Rule #2: Don’t outsource a welcome. “It’s always better for someone’s manager to be the one to show them around and make introductions,” says Guthrie. That said, everyone should know the new person is starting and should proactively walk up to greet them as well. These introductions should serve a purpose. Everyone should know to say, “Hi, my name is Joe. I work in product and am responsible for X.” (Not just “I’m Joe, I sit over there.”) You want to give your new hire pieces of a puzzle that will fit together quickly so that they understand the team and how they work together.

- Rule #3: Keep the first day light. “Very few people get a good night’s sleep before starting a new job, so be respectful of that. You can have some meetings planned, but remember there’s a lot of information coming at that person and it’s hard. Even the most confident, ‘I’ll dive right in’ person is still learning a bunch of new names and faces. Set the expectation: 'This first week you should not be here past 5pm. Your job is to be a big sponge, and we want you to have time to reflect and recharge before coming back every day.'” Even if you talked about long, grueling hours during the interview process and the candidate agreed to them — even if you said, “We literally never go home, we have no lives” — don’t make that the case the first week. “People pick up on so many written, verbal and unspoken cues when they start a new job. Be sensitive to the sensory overload.”

- Rule #4: Clue them in on the vernacular. Every company has its own secret language, especially if people have been working together for a while. It’s made up of inside jokes and shorthand that can be intimidating and even alienating for someone new. “When I directed HR at Readyforce, we worked with so many hilarious people, we had all of these jokes with each other. So part of our onboarding was literally looping people in on insider stuff, saying things like, ‘Oh, when so-and-so says this, this is what she means...’” Figure out what those things are at your company, and make them inclusive in your onboarding. Don’t let them make a new hire feel like an outsider.

Day One is your chance to be who you said you were in the recruiting process.

4. Write and distribute your user guide.

As a first-time founder and CEO of health technology startup PatientPing, Jay Desai was anxious about messing up with his 100+ employees — and particularly the seven who report directly to him. Throughout his career, he had seen too many immensely talented and productive teams stall because of a subtle misunderstanding on how to best work with each other — and the trust that formed or dissolved from those interactions.

So, he penned a user guide — similar to the kind that’d accompany a rice cooker or bassinet — but this one deconstructed how he operated optimally, when he might malfunction, and how others could use him to their greatest success. To create and the compile the guide took a intense self-reflection, drawing both from his early management mistakes at leading PatientPing and a career in finance (Parthenon Capital, Lehman Brothers) and healthcare (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CVS Health).

The goal of a user guide is to set blindingly clear expectations on how to collaborate without extra second guessing. The reality is that we all could use some level of assurance, regardless of how well we think we read people. It’s also a transfer of trust, as it declares how someone operates and falters — essentially how I’m built. “There’s upside even with the small first step of agreeing to create a user guide for your team. It’s an act of empathy, an acknowledgement of implicit power dynamics between managers and employees, and recognition that the group is made up of different people with distinct styles,” says Desai. “Then when you write one, the act speaks for itself. It says, ‘I know you want to make me happy and I want to make you happy, too, because I really want you to succeed. Let's just make that easier for each other by drawing a social contract on how we can relate. It helps us feel ok being ourselves without being misunderstood and a powerful tool to scale fast.’”

If Desai’s explanation still isn’t enough, here’s a list of quick hits on how user guides have helped PatientPing and him:

- Show, not sell, transparency to candidates. “During the recruiting process, candidates will inevitably ask about culture. I usually say that I try to be transparent with who I am, what the company is, and what our values are. Of course, they’ve heard all that before from managers in their career,” says Desai. “Then I give them a preview of my user guide as a bit of an insight into our management style and to show we value self-awareness — and the collaboration that comes from it. Candidates find it illuminating to read, and helpful to see before making their choice about the role.”

- Give new hires a full onboarding. “During onboarding, the first four days are heavily function and business-specific. On Friday, I have my first 1:1 with the new hire,” says Desai. “To prepare I send them my full user guide midweek, asking them to read it and come prepared to begin a discussion on how we will build trust. Their reaction is usually ‘This is great. I’m going to write my own companion user guide.’ They'll draft their guide and send it to me two weeks later. By the first month, we develop an understanding of each other that forms a strong foundation to get cranking.”

- Redistribute cognitive overhead beyond the basics. “Time is finite — especially at a startup. Leveling up the types up questions I get means spending time on more difficult topics — and that’s typically where there’s more growth,” says Desai. “With a user guide, people don’t waste time wondering if they should respond when I forward an email as FYI or how to share business updates and so on. It’s all in the guide and so we can move quickly to more impactful discussions.”

- Actually put your weaknesses on the table. “Many ‘thought leaders’ champion vulnerability and how it’s beneficial to get your weaknesses out in the open. But that’s obviously hard or more people would do it. When it’s on paper, they can learn and digest your weaknesses asynchronously, versus try to simultaneously absorb and react to what they’re hearing from you,” says Desai. “As the leader, it’s important that I share my weaknesses first — that I entrust others with it. That sets the tone that you’re going to be vulnerable as a manager. Show that you’re not perfect and make mistakes. Your employees will feel more empowered to do the same.”

Here is Desai’s user guide in full, as of early 2018. It’s a dynamic document that he returns to to revise, as he learns more about himself and his team. Therefore, the following version is a snapshot in time — but a helpful template regardless.

People always harp on the importance of building trust and communicating — but they rarely say how. Write your user guide. Ask your team to reciprocate. That’s how.

5. Reference this equation to determine who and how much to trust.

Anne Raimondi has an all-star management track record, including Director of Product at eBay, VP Marketing at SurveyMonkey, CRO at TaskRabbit, SVP Operations at Zendesk, and COO at Earnin. Across her career, she’s seen how trust is non-optional at technology startups. Not only can distrust between co-founders be fatal, but the terrain at startups changes rapidly, people move into new roles and challenges, and at a certain point there's an influx of new people.

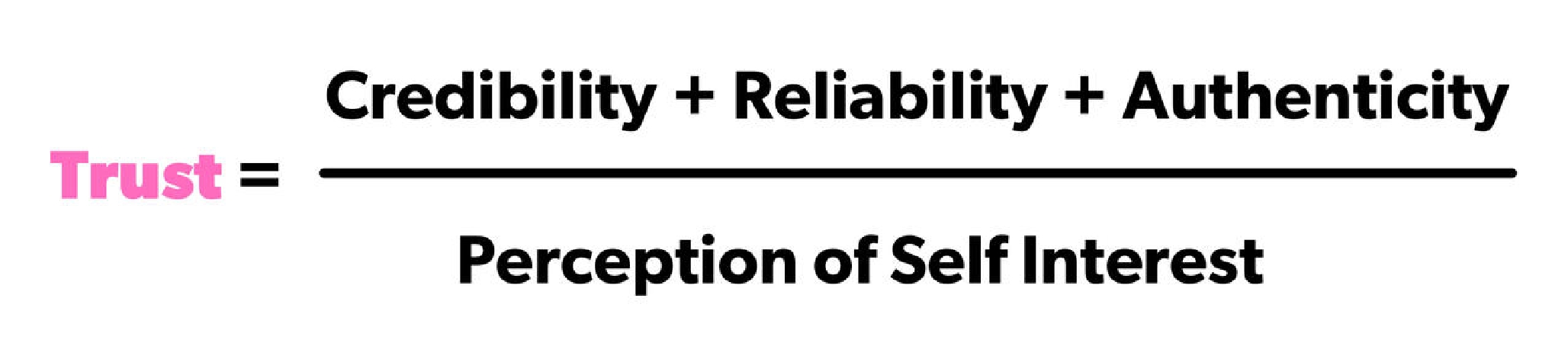

There's no time to doubt or be doubted — and she’s found an equation that can help people diagnose and repair trust. It comes from a book called The Trust Equation by Steven Drozdeck and Lyn Fisher, which offers the following equation for how humans determine who and how much to trust:

Essentially, the amount you trust someone is the sum of how credible you believe they are on a subject, how reliable they've proven themselves to be over time, and how authentic you think they are as a person, divided by how much you think they're acting in their own self interest. Looking at her colleagues' relationship through this lens, Raimondi helped them diagnose when and how trust had eroded, and eventually work with them to heal the rift.

Read on here to learn how each of these variables might break at startups and what Raimondi suggests to do about it. She also digs into how to use this equation to design a good career trajectory.

6. Work toward a shared consciousness.

Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates described General Stanley McChrystal as "perhaps the finest warrior and leader of men in combat I ever met." As a co-founder of the McChrystal Group and CrossLead, the retired US Army general has built consultancies that help leaders at companies become more effective and adaptable. Many of the companies that hire the McChrystal Group or CrossLead might do so because they envision former Navy Seals parachuting into their company to whip their employees into shape with strict discipline from the top, as you’d expect from the military.

But what these consultancies do is less about discipline, and more concerned with lack of trust and common purpose — essentially the need to develop shared consciousness throughout an organization that will allow leaders to empower people to make decisions faster on their own.

According to McChrystal, the problem in Iraq wasn't that operators were disobedient or didn't work hard enough. The problem was that the chain of command was too slow to move as quickly as the enemy did. And there were so many things happening in so many places, there was no way for the small group of senior leaders to have enough information to make all the right decisions on their own.

"The wisest decisions are made by those closest to the problem — regardless of their seniority,” General McChrystal says.

His forces came to realize that the only way to move as fast as their enemy was to empower people on the front lines to make decisions as quickly as they could learn new information. But how do you do this when leaders still believe the people on the front lines don’t have enough information to make the right decisions?

This is why trust and common purpose are so critical. Leadership must first trust that employees understand the organization's context and goals enough to make decisions on their own. But how can leadership ever trust their employees if they won't freely share the information people need to make good decisions and let go enough to allow those employees to prove themselves?

McChrystal's answer: By developing shared consciousness. This means getting to a point where you trust almost anyone to make decisions on their own because you believe they have the same information and objectives you do. This is one of the core organizational skills CrossLead helps their customers develop.

While McChrystal’s consultancies employ a number of tactics to help with this, his way of combining strategy and execution is most powerful at transferring trust throughout an organization:

In typical “strategy” sessions, leaders might talk about the organization's goals, strategies, resources, competitors, etc. The senior leaders then expect next tier leaders to cascade the relevant parts of what they decide down their ranks. They assume that feedback on the strategy will eventually trickle it's way back up to senior leadership... or not.

Not only is this process too slow, but far too lossy. Given the lengthy game of telephone that usually follows, it's no wonder leaders don't trust their employees to understand strategy. Usually, each leader ends up with their own interpretation which they then further filter based on how much they think their group of employees needs to know. Furthermore, they likely decide which parts are the most important based on their own group’s incentives. As a result, they never get the feedback they need to get better or apply critical information from the front lines.

McChrystal's solution to this problem is to combine the process of talking about strategy with the communication of that strategy to hundreds or thousands of people. While he was active in the military, they did this with a daily, large, inclusive 90-minute strategy meeting with leaders and soldiers from across the various branches of the military as well as people from all the branches of homeland security.

In this well-choreographed meeting, there might be a hundred people in the room and thousands of people listening in on a call. Astoundingly, any of the thousands of people dialed in could speak at any time! McChrystal would be the first to admit it was a long process getting to where this worked at scale, but the end result was a hive mind that ensured everyone was acting with the same information and could be trusted and empowered.

This is far from the end of the Review's wisdom on trust, communication and transparency, check out the full articles referenced above as well as others focused on the three conversations managers must have to develop and build trust with their people and how to navigate some of the gnarliest startups conversations.

Illustration by David Madison/DigitalVision/Getty Images.