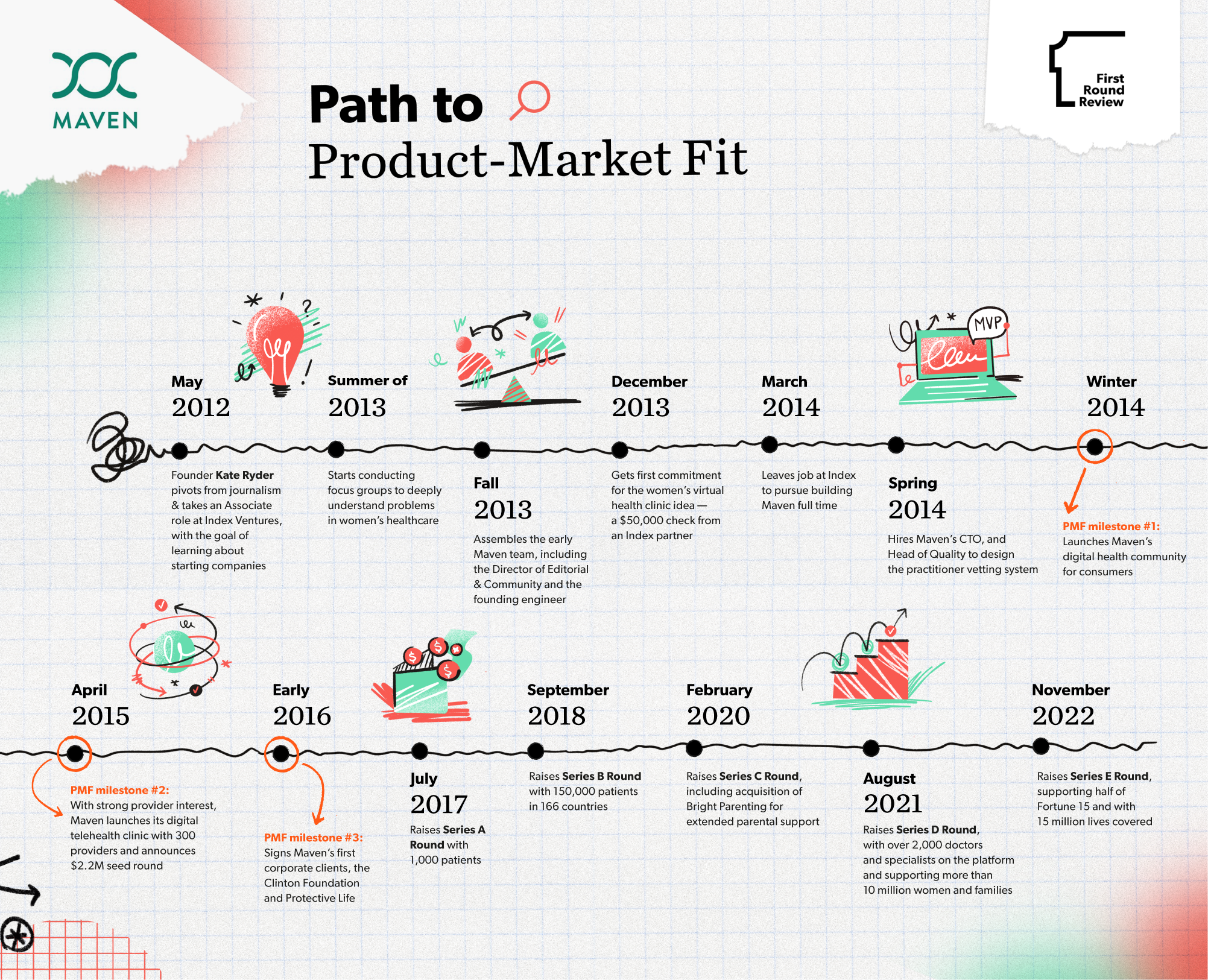

This is the second installment in our series on product-market fit, spearheaded by First Round partner Todd Jackson (former VP of Product at Dropbox, Product Director at Twitter, co-founder of Cover, and PM at Google and Facebook). Jackson shares more about what inspired the series in his opening note here. And be sure to catch up on the first installment of our Paths to Product-Market series in this interview with Airtable co-founder Andrew Ofstad.

Plenty of successful businesses have been built by founders who weren’t their product’s core customers. But Maven was created on a bedrock of founder and CEO Kate Ryder’s commitment to creating better healthcare outcomes for women, for parents-to-be, and more broadly for parents — just like herself and her cohort of friends.

As Ryder entered her 30s and found herself surrounded by people starting to have kids, she got an up-close look at just how underserved this segment of the population was in the healthcare system.

It’s one of the most pivotal moments in any new parent’s life: You step out of the hospital doors, delicately strap your newborn into their carefully-chosen car seat and head home for the first time — leaving the safety of the hospital (and the expertise of its doctors and nurses) behind. “It’s such a vulnerable feeling. You leave the hospital and just think, ‘Well, what now?’” says Ryder.

“An OBGYN once said to me: ‘There are five things that need to happen when you’re starting a family. There’s getting pregnant, the actual pregnancy, the delivery, postpartum recovery — and then there’s the cost of it all. And typically two of the five things go wrong,” she says.

Pregnancy, childbirth and early parenthood form a complex, tangled web of healthcare components: fertility doctors, genetic counselors, pediatricians, doulas, lactation consultants, pelvic floor therapists and so on. “They’re all disconnected, many are not accessible through insurance, and families are expected to navigate this maze on their own to find the right team to meet their needs,” says Ryder.

To tackle this delta head-on, she founded Maven, now the largest telemedicine clinic catering to women and families. The company hit unicorn status in 2021 after raising a $110 million Series D — making it the first female-led telemedicine startup to achieve the accolade (and along the way to building a billion-dollar company, she’s had three kids of her own). Just recently, Maven announced a $90 million Series E.

Maven’s platform combines an expansive, specialized telehealth network of more than 30 provider types with individual care navigation to support all parents and all paths to parenthood, from fertility through pregnancy, parenting and pediatrics.

Although Maven is a B2B company (most folks access the platform for free through their employer or payer that partners with Maven), the path to product-market fit started with a B2C community, opening up conversations and solutions for women looking for answers to their most personal questions about their health and family-planning journeys. As Ryder tells it, this consumer-first phase of the company was critical to unlocking the insights she needed to begin building a B2B product.

Let’s rewind the clock.

EXPLORING IDEAS:

With sights on building a company, some founders go get industry experience — or start diving into product building and learn as they go. Ryder took a different path, taking a role with a different altitude so she could learn about many markets and zero in on where there was the most room to build.

“I had been working as a journalist, writing about finance and business for The Economist, but I wanted to start a company. My dad was an entrepreneur, and my mom and aunt also had a business together. I grew up around it,” says Ryder. To get closer to the action, she took a job as an associate at Index Ventures at their London office in 2012 — and made a peculiar pitch in her interview loop. “I didn’t know at the time what company I wanted to start, but I knew I wanted to start something. During the interview, I made it clear that I didn’t necessarily want to climb the ladder to become a VC. I wanted to get up close and learn about starting a company, and I was willing to do whatever job they needed in the meantime while I learned the ropes,” says Ryder.

For the next two years, she drank from the firehose, learning the ins and outs of the fundraising process, picking up on what firms are looking for when they cut a check and building a network of founders and investors — many of whom would later angel invest in Ryder’s eventual idea for Maven.

On the side, she started playing around with a few different ideas, including a vitamin subscription box tailored to folks with genetic diseases in their family, a concept that she abandoned after realizing the vast complexities that come with a physical supply-chain business. She also toyed with an idea to make ramen healthy — think a cup of noodles that’s like a shot of B12 vitamins. But her lessons from the VC world taught her to go after the largest possible market, so she expanded her scope.

Whenever she sat down with friends to catch up over drinks, the conversation always seemed to lead back to one topic: family planning and fertility. “As my friends and I entered our 30s, it was all we could talk about at times. I had friends that had difficulty conceiving and needed fertility treatments, and others who had really complicated pregnancies or debilitating postpartum depression. There’s no one-size-fits-all experience when it comes to having a child,” says Ryder.

Look for the biggest green space.

And as a VC associate, Ryder was beginning to read the tea leaves that the industry was starting to shift, opening up new opportunities to increase access to high-quality care. “At Index, I saw that digital health was really in its first inning. In 2013 telehealth was beginning to gain a little bit of traction. But women’s health and family planning were still largely underserved,” she says.

Ultimately, Ryder was looking for room to build. She’d seen up close that the most successful founders made space to pivot and iterate away from their original vision. “Healthcare is an incredibly complex problem. But it’s also a huge industry, which means there’s room to pivot around until you find product-market fit if your first idea doesn’t hit,” she says.

Pivoting is key to creating a lasting business. Don’t choose a problem that’s so narrow that you don’t have the space to explore other ideas.

ASSESSING THE PROBLEM:

Still working in venture and living in London, Ryder hopped across the pond to conduct a few focus groups in the U.S., assembling a group of around 50 women to go deep on the problem. “I wanted to really validate whether or not this was just a problem my friends were experiencing or if it was a universal problem,” she says. Far too often, folks building companies in fields that they’re the target audience for skip this step, instead jumping straight to building. But extensive problem validation is critical, even if you’ve got a super strong hunch and some anecdotal feedback to support your hypothesis.

To fortify her footing, Ryder facilitated discussions with cohorts of 10-15 women around all things pregnancy and family planning. “I asked tons of questions about how they related to their health care. A key theme that arose was access — whether it was problems around lack of access to specialists through insurance, limited time to access mental health care for postpartum depression with a newborn at home or financial barriers to fertility treatments,” she says. “You’d hear stories about a woman needing to see a pelvic floor specialist after giving birth, but no appointments were open for three months with a doctor in their network. It was clear through these conversations that this was a much wider problem than just my group of friends,” she says.

Women are asked to be the Chief Medical Officers of their homes. I wanted to give them a team of experts at their fingertips.

Don’t shy away from competition early on.

To further assess the existing landscape, Ryder also brought would-be competitors into the focus group circles. “There were a couple of telehealth companies and wellness communities that existed at that time, so I put them up on the screen just to get the focus group’s reactions,” she says.

“We had just talked about these problems in the healthcare field, and these were the companies trying to tackle some of those challenges. What did they think of the value prop? I vividly remember one of the women saying she thought it looked like a real estate company,” says Ryder. “The first wave of digital health companies seemed to over-index on regulatory compliance and speaking to providers. They weren’t tech companies building delightful customer experiences. That’s when I knew there was a huge opportunity.”

ASSEMBLING THE TEAM:

Ryder had thrown a dart and felt like she hit a bullseye on the problem. She was still working full-time at Index, but knew she was nearing the inflection point where she needed to focus 100% of her energy on Maven. “In December 2013 I went to lunch with Kevin Johnson, an Index partner who was focused on biotech and softly pitched him my idea for a women’s virtual health clinic. He bought in and wrote a $50,000 check,” says Ryder.

This was a signal that it was time to focus on Maven full-time, and start assembling the early team. But rather than over-rotate on finding the person with the most stacked credentials, she focused on mission alignment. “We didn’t look like a traditional founding team. I see other founders who obsess over getting folks on board with dazzling resumes. But I wanted people who would run through walls to achieve our goal,” says Ryder.

Startups are incredibly hard work and they require grit. The thing that gets you through those tough moments is a deep commitment and belief in the mission and solving the problem.

So she looked for the early team in some unconventional nooks and crannies:

- Play the long game. “The first person I called was my friend Sally Law Errico, who I used to work with at The New Yorker. A couple of years back she had pitched me an idea for a mocktail for pregnant women, so I knew she was interested in working in a similar space. She agreed to be our first employee on a part-time basis as our Director of Editorial and Community,” says Ryder. While not the conventional first startup hire, Ryder had the conviction that content was going to play a huge role in the paradigm shift that was required to get folks comfortable using telehealth solutions.

- Get face-to-face. Non-technical founders often fret about how to find the technical talent they need to bring their visions to life. Ryder’s counsel is to get creative and stay persistent with putting yourself out there. To find her founding front-end engineer, she canvassed engineering meetups, where she met her next hire. “I basically walked up to everyone there and asked if they were an engineer and whether they were interested in healthcare. And Suzie Grange was the first person who said yes. We went and had lunch together and I told her about the company and the mission, and she agreed to do some work on the side,” she says.

- Put on your founder hat — even off the clock. Even Maven’s founding CTO, Zachary Zaro, crossed paths with Ryder in unlikely fashion. “I was attending my best friend’s wedding and knew Zach was going to be in attendance, and that he was a top-notch engineer. I switched the seating cards so that I ended up sitting next to Zach and basically pitched him on the idea of joining Maven for the entire wedding,” she says.

BUILDING THE MVP AND FUNDRAISING: LEVERAGING COMMUNITY TO EXPAND ON THE EARLY VISION

Tapping into her network of investors and entrepreneurs, Ryder admits that assembling the company’s early fundraising efforts were unusually smooth sailing, eventually closing a $1.2M friends and family round.

Ryder and her husband then moved back stateside to start building a digital health clinic specifically for women’s and family health, where folks could access specialists for their unique needs, not just a one-size-fits-all solution the healthcare system was dishing out.

They started tackling the process of getting connected to providers who would eventually join the digital clinic, building a web-based practitioner onboarding assessment to screen potential leads and vet quality. “Getting the first couple dozen providers to sign on was pretty easy. Women’s health is so underserved — we have the highest maternal death rate in the developed world. The believers were excited to join our mission,” she says.

To expand beyond those early evangelists, though, Ryder had to get creative. She combed insurance company websites for provider addresses and sent them marketing postcards with the tagline, “Do you want to revolutionize women’s health?” which directed them to the provider webpage with the screener questions.

Inspired by the focus group conversations, Ryder also started building a B2C community where folks could connect with one another. “I wanted to create a digital community where women could continue to have these conversations, ask questions and help one another tackle the tangled web of our healthcare system. This approach would also help us continue to prove out our concept as we were thinking about raising money,” she says.

They spun up a low-lift digital community within a few months and launched in beta, with the goal to eventually convert these community members to digital clinic patients, once the telemedicine platform was built.

Ryder remembers the exact moment she felt like the digital community was catching on. “A community member asked a simple question, and we had four different provider types answering to add their input — an OB-GYN, a doula, a midwife and a nutritionist. Oftentimes, the answers to fertility and parenting questions aren’t black and white. It was incredible to see so many different perspectives represented in a community forum,” she says.

As the community continued to pick up speed, building out the digital clinic required more capital, so Ryder set her sights on raising more money from institutional investors to start getting the company off the ground. But on the next leg of her fundraising journey, she faced a much sharper incline. “Back in 2013 and 2014, very few VC firms had female investors on their teams. And most men at the time just weren’t buying into our core belief — and our data — that this was a universal problem. They thought women’s health was niche and cringed when we would bring up things like pelvic floor therapy,” she said.

But stories from Maven’s customers — women underserved by the healthcare system — kept her pushing forward after doors kept slamming shut. After 40 rejections, Maven’s Series A round was eventually led by Lauren Brueggen, a mom of three from a small B2B fund who believed in the problem. Since then, most of Maven’s additional rounds have been led by female investors.

And as they continued building out the MVP for the digital clinic, Ryder and her team tapped back into the consumer community for feedback. “We knew eventually the economics for Maven relied on selling to employers, but we wanted to learn as much as possible from consumers.

Even if you’re building a B2B product, find a way to get that direct line to your customers in the early days.

LAUNCHING:

Eventually, Maven launched the virtual clinic in April 2015 with 300 providers. And while Ryder and the team set their sights on a flood of traffic and booked appointments on launch day, that wasn’t quite what happened.

“At the time, we were one of the first apps to be built with Swift, an iOS programming language that Apple developed. Talking to folks on the Apple side, they were definitely winking that they would feature us in the App Store on our launch day. I remember writing to all the providers that they should prepare to open up their schedules because there was going to be a huge influx of patients coming from this Apple feature,” says Ryder. “But Apple didn’t actually end up featuring Maven. I think on launch day we got one doula appointment from someone who had read about us on TechCrunch.”

It turned out that changing consumer behavior when telemedicine was just entering the parlance was a tricky needle to thread. “This was 2015. Talking to a doctor over FaceTime was much newer and weirder at the time,” says Ryder.

Her advice to other founders? Don’t get deterred, and do the things that don’t scale. To generate more user signups, the Maven team encouraged providers to jump into the consumer Maven community and answer questions that folks were posing to the group, which pushed some of those community users to sign up for the digital clinic and access more expertise. Ryder and team also pounded the pavement. “We would stand in a park and try to sign consumers up with field marketing. We’d hire a bunch of interns to go canvas the city and try to get eight appointments. We set up a table at the New York Marathon. It was a grind,” remembers Ryder.

Make sure your early team is really mission-driven and ready for the bumps — because there will always be bumps.

Maven also started making the push towards their ultimate goal: selling to employers. Ryder tailored the pitch accordingly. “Employers are in the best position to buy — they want happy and healthy employees and they want women to come back to work after having babies. So I was going around to different employers and speaking their language about how Maven could help them cut their high healthcare costs and provide a compelling benefit that stands out from competitors,” she says.

The company’s initial pitch to employers was centered on its first enterprise offering, Maven Maternity. The value prop was that by offering Maven as a free benefit, their employees could have safer, healthier pregnancies and deliveries with access to the specialists they need — thus smoothing the path to a happier and healthier return to work. They would also have support during key areas of maternity that were absent in the care model: like supporting women through miscarriage, and during the postpartum period.

The first corporation that signed on was the Clinton Foundation, with Snap following shortly after. By 2017, Maven launched its second enterprise offering, Maven Fertility. This product covered all pathways to parenthood, including surrogacy, adoption, egg freezing, and IVF/IUI. It was another key area of the family care model that was underserved by the current system of care, and Maven’s product supported both couples suffering from infertility as well as providing equitable support to LGBTQ+ community looking to start families.

LOOKING FORWARD:

In retrospect, the path to product-market fit for Maven was a story of the power of networks. From the initial idea coming from conversations amongst friends, to her earliest employees and first checks, there were multiple personal touchpoints that drastically impacted the company’s trajectory. Even the name Maven was solidified when Ryder emailed a list of 10 name ideas to her closest friends, who voted for their favorites.

Fast forward to today and the Maven platform now has more than 2,000 doctors, caretakers and specialists spanning 30+ specialties and 350+ subspecialties in its network and has 15 million lives under management. Most customers access Maven through their employer, including more than half of the Fortune 15, and the company sells to health plans as well, recently inking a partnership with Blue Shield of California and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

As for what’s next, the power of Maven’s community roots is influencing the company’s direction and they’ve recently added services and specialists for menopause, based on conversations and interest in Maven’s digital health community. They are continuing to expand their global offering as well. Maven now covers nearly 1 million lives outside of the US, and they continue to see massive global demand for equitable family-building financial support and care.