“My design philosophy has always been that you should design something for someone. It's hard — impossible even — to design something really good for everyone,” says Karri Saarinen.

That credo has also proven to be a successful strategy for finding extreme product-market fit. Saarinen has built Linear to impress one very particular someone: himself. And it turns out there’s a massive market of folks just like him — IC product builders itching for a better way to track their work than the incumbent tools can provide.

Saarinen has always had an eye for good (and bad) design. Growing up in Finland, he recalls shopping for a new bike at around eight years old and being struck by how ugly all the options were. “I just couldn’t understand — if you make a bike, why can’t you make it nice?” he remembers thinking. “Years later, I realized you need a designer to do that, and I learned that was a career path.”

His design instincts paired with a curiosity about software. Playing games on the Commodore 64 sparked an early interest in computers, and as a teenager, he learned how to code with rented library books about HTML. His first real job was running a web dev agency for local Finnish businesses — and he soon understood how universal the need for better digital design was. “Every company I worked with was good at programming, but very bad at design. So I started to think about design wherever I went.”

Much like his childhood frustration with bike design, when Saarinen later became a principal designer at Airbnb, he was dissatisfied with the company’s project management software. “When I first started using it, I thought, ‘Why is it so messy and complicated?’” he says.

So in 2019, Saarinen teamed up with his Finnish friends Jori Lallo and Tuomas Artman to design an issue-tracking tool that devs — like themselves — actually like using.

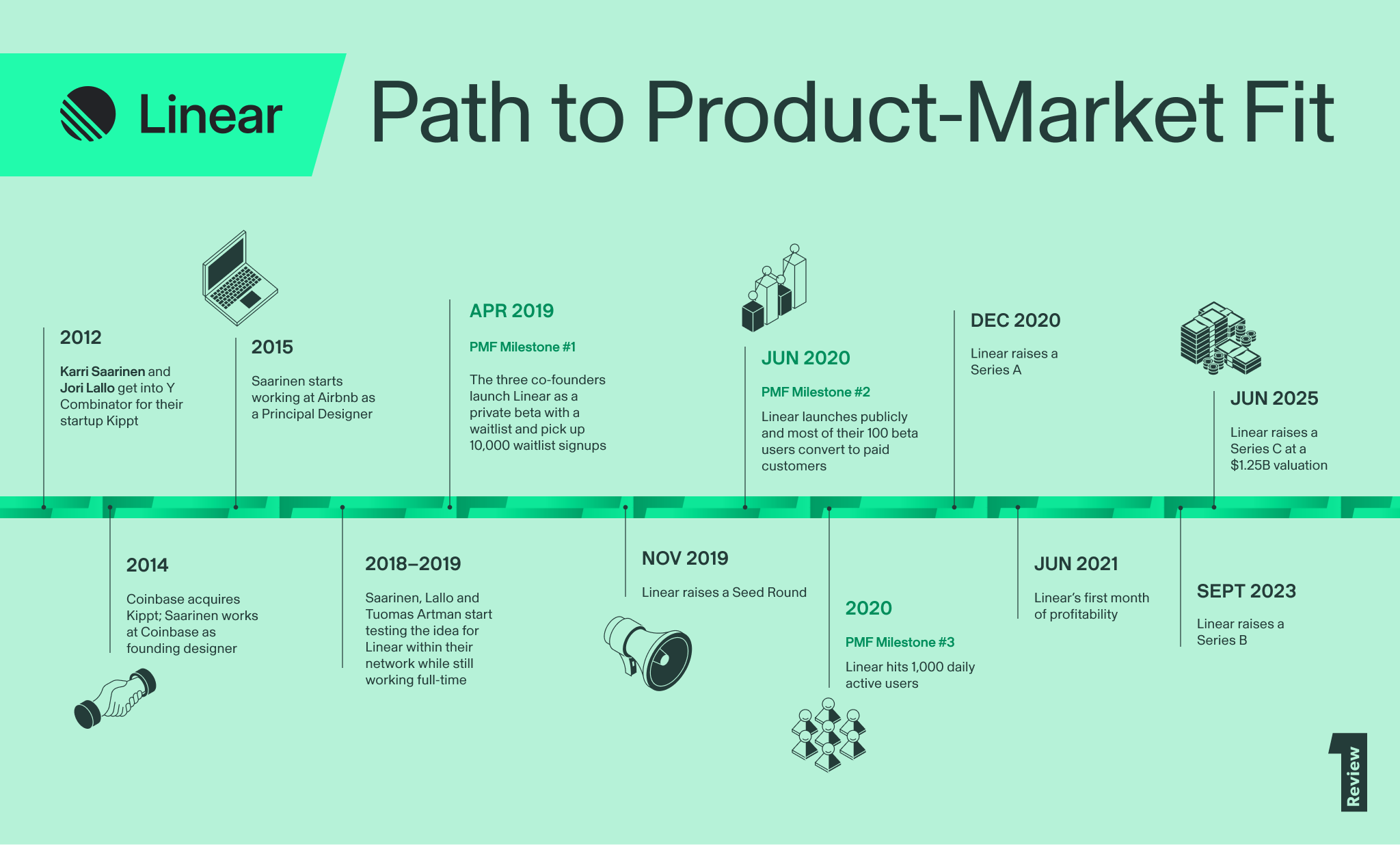

Flash forward to today, and the founders’ thesis that issue tracking can and should be both efficient and enjoyable has resonated widely. Fresh off of a Series C fundraise, Linear has soared to a $1.25B valuation, winning over both fast-growing startups and enterprises switching from legacy software, with companies like OpenAI, Ramp and Vercel as customers.

In this exclusive interview, Saarinen traces the deliberate early moves behind Linear’s success, from running informal user research with colleagues at Airbnb to narrowing in on — and designing a remarkable experience for — an ultra-specific ICP (one that mirrors the founders themselves).

Preludes to Linear

In 2011, Saarinen had his first go at running a startup with Kippt, a web bookmarking tool that he and Lallo initially built as a side project. Like most software products of that vintage, they launched it on Hacker News — and within a few months netted 10,000 users, which gave them the confidence to apply to Y Combinator’s 2012 batch. They got in, trading Helsinki for the Bay Area to work on the company full-time.

But beyond the initial burst of users, Kippt failed to gain much traction. They couldn’t find a viable route to monetizing — advertising only made sense with a massive user base that Kippt didn’t have, and the tool’s appeal among far-ranging personas from teachers to engineers meant there wasn’t an obvious customer group who wanted, or was able to, pay for it.

“We learned that it's really hard to turn a company into a business if you didn't set out to build one,” Saarinen says of Kippt’s trajectory.

But Kippt proved to be a pivotal first step in Saarinen’s entrepreneurial journey. The co-founding duo were in the same YC batch as Coinbase founder Brian Armstrong. Coinbase’s early team didn’t have any designers, so Saarinen would often serve as a design advisor, and Armstrong kept nagging him to join. He wouldn’t take no for an answer: Coinbase acquired Kippt in 2014, and Armstrong brought Saarinen on to be the founding designer as the startup skyrocketed from a team of 12 to over 100.

Saarinen later left to join Airbnb in 2015 as a principal designer, which is where he first had the idea to create a better project management platform for software development. He’d just begun using Jira for the first time and found the user experience frustrating. “So I refused to use it for a long time,” he says.

But realizing that boycotting the tool was hardly productive for himself or his team, he took matters into his own hands and designed himself a better version. “I created a Chrome extension that loaded up a custom CSS for the Airbnb Jira instance. I changed the colors, the styling, the hierarchy of the views and the screens, and removed stuff I didn’t find necessary,” he says.

His custom Chrome extension proved popular with coworkers. “I launched it internally as a ‘simplified, nicer looking Jira,’ and it actually got about 100 installs within Airbnb.”

Several years later, Saarinen got together with Artman and Lallo for beers. Artman had moved to Uber as a software engineer, and Lallo had stayed on at Coinbase. They both had the same frustrations with Jira that Saarinen had experienced. At the bar, Artman and Lallo told Saarinen: “We use all these software development tools at our companies and all of them are quite bad. I think we could build something better.”

They suspected incumbent software was bad because it targeted people who weren’t even using the product — procurement, IT leadership — instead of ICs. “We believed that we could build something that’s very good for end users. And that would be really valuable because all the work they’re doing is tracked there, and the system can be a real-time source of truth,” Saarinen says.

Saarinen was sold from that first discussion at the bar. “When we first decided we wanted to start a company, the very next sentence was, ‘This is the idea.' We didn't explore other ideas.”

Validating the idea

The three friends didn’t rush to put in their two weeks’ notice to start working on this issue-tracking startup. Instead, they spent over a year letting the idea simmer while still at their day jobs — and running light user research with their colleagues.

They already felt deep conviction in the idea given their personal frustrations, but they wanted to validate that their experience was shared by people just like them, who were:

- ICs (not managers)

- Product builders (software developers, product managers and designers)

- Working at fast-growing startups (Airbnb, Uber and Coinbase)

“We were always the type of people that we wanted to build something for,” Saarinen says of himself, Lallo and Artman. “We weren’t in management positions — we were in high IC positions because we all loved building things. And it didn’t feel like the incumbent tool was helping ICs actually do the work, which is weird, because the productivity of any company comes from ICs like engineers and designers.”

Their approach to these conversations was informal. “It was pretty random and unstructured,” says Saarinen. They started by asking coworkers, along with other friends in the tech world, including some founders, these questions about their companies’ software dev project management tool of choice:

- What do you think is bad about this tool?

- How would you want to improve it?

- What would make you more productive?

Just about everyone had complaints, but Saarinen noticed that most folks assumed this wasn’t a problem that could be solved. “What was interesting was that a lot of people had lots to say and clearly saw a problem. But no one said, ‘I wish you could solve this.’ They hadn’t even thought about it. The incumbent in this market is like the floors in the building — you don’t think about the floors, you just walk on them.”

One of the biggest grievances that surfaced during these conversations was how slow the performance of tools were. “So that made us think, what if we can solve the speed issue? What if we can build a tool that’s never slow?” he says.

Saarinen now credits much of their early conviction in Linear to this pre-work they did before quitting to work on Linear full-time.

Sometimes it's good to not just build immediately. We didn’t want to commit right away and move really fast. We wanted to take some time to talk to people and form our thinking around this idea.

Designing a prototype usable by the founders

The founders spent roughly a year ideating and validating on the side, meeting every Wednesday at a bar near their offices to discuss what they had learned from friends and coworkers that week.

In March 2019, they resolved to quit their jobs and start building the product. But they didn’t want to spit out a prototype just to get it out there. They were determined to build something that met their own high bar, which meant designing a tool with deep functionality from the outset — that was also fast.

“We wanted the first product to get to the state where we could use it every day for our own basic workflows,” says Saarinen. “We were the first ideal customer. So we just had to build something nice for ourselves that actually worked.”

They were also extremely opinionated about how every nook and cranny of this software should look and feel. Saarinen says this approach to product design emulates Apple’s philosophy, which creates a universal experience of using a Mac or an iPhone by allowing users to change some things, but not everything. “I don’t think you can build the optimal tool for anything if it’s very flexible or endlessly customizable. So from the beginning, we had a strong opinion of what a good workflow looks like and we provided standards and defaults for how to operate,” he says.

It took the founders about a month to whip up a working prototype, then they got it in the hands of 10 friends to play with. One of those friends was also a founder whose entire 10-person team liked the product so much they all switched over to Linear. That fed the trio’s confidence enough to bring the product to more people.

Because we did so much pre-work and pre-thinking, a lot of the architecture was basically built into the product by the time we started.

Launching a private beta to a small cohort of motivated users

In April 2019, one month after quitting their jobs and finalizing the prototype, the founders rolled out an invite-only beta with a blog post, a tweet, and a signup for an email waitlist.

“We wrote the blog post very clearly to ourselves — using the language I would want to read if I were learning about this for the first time,” says Saarinen.

In a way, this language was almost like a signal to other people who felt the founders’ pain and sought a better experience. They weren’t trying to woo as many new users as they could; instead, they were extremely deliberate about choosing the right first few people to test out Linear.

At the bottom of the launch blog post was an email signup that led to a survey. The survey asked questions like, ‘Why do you want to use it and what are your current problems?’ It was designed to seem optional, but it was actually a way for the founder to identify the most motivated and promising set of early users — who ticked every box of the ICP persona.

“We knew Linear was never going to be a fit for everyone right out of the gate. So we didn't want to launch publicly and have a ton of people checking it out for a day, and then leaving, thinking the tool sucks,” says Saarinen. “So we wanted to control the process by inviting the right types of users and then seeing what kind of feedback they’d have.”

He estimates that Linear collected around 10,000 emails on the waitlist, and roughly 10% of them became users during the first year of the private beta. He would handpick people based on their survey responses and send them an invite to Linear, adding only around 10 people per week.

Even among those vetted early users from the waitlist, not everyone loved the product. Saarinen didn’t sweat over it. “When you create something new, there's always going to be people who don’t like it, especially in the beginning. So I don’t think you should overindex on why someone doesn’t like it — you should index on why someone does like it,” he says.

To do that, the founders struck up a rapport with early users who were in Linear every day, emailing them weekly and tracking feedback they submitted while using the app. With the strong traction from the private beta, Linear raised a $4.2M seed round in November 2019.

I wanted to find the most motivated users and focus on them as much as possible, because they could help us build this thing.

Enable your happiest users — and squash blockers for prospective ones

The selective cohort approach gave the founders higher quality feedback from people who were using Linear just as the founders intended — to manage bread-and-butter daily software work. “With each new cohort of 10 users, every week we basically made a new version of the product,” Saarinen says.

He bucketed the feature sets the team built out for the early user cohorts into these two categories:

- Enablers: The features that will make existing users extremely happy

- Blockers: The features that will remove barriers for people who fit the ICP bill, but are for some reason blocked from joining

One of the big blockers the Linear team discovered while vetting waitlist signups was that they’d built the whole login process with a Google authentication — which meant folks couldn’t get set up in Linear if they didn’t use the Google Workspace. They realized that when it was time to launch publicly, they’d need to revise the onboarding process with a general email signup.

“Most of the time, in the early days, you’ll be focused on building enablers to make the group of people who are really motivated about using your product extremely happy,” says Saarinen. “But every now and then, look at your list of blockers so that you can open up your product to a larger user group, and they can be happy too. You shouldn’t optimize too much for either — you should try to do both.”

Scaling up by building more for the ICP

To determine when to launch publicly, Saarinen watched for steadily high retention rates. “If you’re losing the majority of your first users, you shouldn’t launch it publicly because you’ll just lose even more people,” he says.

The Linear team kept the waitlist up for almost a year, collecting roughly 1,000 daily active users by the time they eventually rolled it out publicly. But the team never swayed from the day-one ICP of IC product builders.

Saarinen says the team wasn’t too concerned with acquiring the next marginal user when plotting the product roadmap. Instead, they focused on building out more workflows for existing Linear users, scaling from just issue tracking to an end-to-end project management platform.

“If you don’t want to grow to more customer types, you can sell more to existing customers. That’s what we’ve done,” he says. “We started with issue tracking because that’s the core need of every software company. But the engineers have to do other work, so we’ve gone downstream of the stack. Engineers need to plan their work — so we built project briefs and roadmaps. And they need to tackle customer feedback, so we recently launched a customer request feature.”

That’s meant opening up the original ICP specification of startup employees to IC builders at larger companies. He thinks there’s plenty of TAM to go around by continuing to build for IC product builders, even if it’s not quite as large as the TAM of a more general purpose tool. “My hope is that every software company uses Linear. And pretty much every company today has some software aspect,” he points out.

He notes that his grand long-term vision to help product teams work more is hinted at in the company’s name. “Ironically, these processes of building software often aren’t that linear. So the name is a bit aspirational. People want linear processes and outcomes,” he says.

Sales as an extension of the product experience

As Linear has moved beyond startups and begun selling into enterprises in recent years, the company has added several dedicated sellers to the team. He admits that he was resistant about bringing in sales help at first — just because they didn’t see the need for it until they began courting enterprise buyers. “Investors told us, ‘Hey, you probably need salespeople,’ and we said, ‘No, we don’t. Who wants to talk to salespeople?’ But then we started talking to customers who actually do want to talk to salespeople. We realized as you go upmarket, buying gets more complicated. Companies have to talk to a lot of people before they can buy something,” he says.

But Saarinen insisted that the sales process clear the same quality bar as the product itself. He was determined to design a sales process that was high-quality (and worthy of unsolicited kudos from customers) — just like the experience of using Linear.

Saarinen thinks Linear’s approach to sales as an extension of the high-craft product has proven to be a differentiator. “Quality for us just means there’s a salesperson who’s super knowledgeable about the product. It’s not that hard or complicated, but a lot of companies don’t do that because they don’t think it’s important. They think that the rep just needs to close the sale, and nothing else matters. But we think it matters because it sets the tone for the customer and how they feel about the product itself,” he says.

Sales is very playbook-driven, which gives you an advantage to do things differently.

Staying small and focused as the company grows

Linear has ticked off some impressive milestones with a remarkably lean team. The founders didn’t hire their first employee until six months after launch, and only roughly doubled Linear’s headcount each year. The company sat at just around 80 people when it nabbed a $1.25B valuation along with a Series C — and it’s been profitable since 2021, just one year after launching the product publicly.

And those brag-worthy stats aren’t the result of setting aggressive OKRs, but rather relentlessly pursuing a harder-to-measure metric: quality.

Quality is our first principle. Every other metric and decision flows from that.

Hitting profitability early on in Linear’s journey created room for that commitment to quality. “We’ve set out to be profitable so that we have the freedom to do things in a high-quality way,” says Saarinen. “What often happens to startups is that the pressure to ship or hit certain metrics means they have to compromise the quality. We think we can win this market by being quality-first.”

Saarinen says Linear’s ethos of building slowly and intentionally can be traced to the founding team’s Finnish roots. “Silicon Valley is obsessed with scale and speed. We try to be more measured — for us, speed and scale come second to quality,” he says.