Yuhki Yamashita was Figma’s ideal customer. Then he joined the company to head up product strategy.

He’d been working as a PM at Uber, where he grew frustrated with the time wasted navigating tools he needed to do his job: redesigning Uber’s rider and driver apps. He had to fumble around for design mocks in Photoshop or Sketch, taking PNG files from designers back into one of the tools to edit them the way he needed. “I was someone who bounced back and forth between product management and design,” he says. “I believed that the boundary between these functions should be more blurred.”

Then he discovered Figma. Uber was one of the first large companies to adopt the tool, and Yamashita happened to be on the team that brought it in. “It completely changed the clunky process I’d been using before. If I needed to put together a product review or make some adjustments, I could do that myself for the first time,” he says.

Eventually, his love of the product compelled him to take a bet on the company itself. This was back in 2019, three years after the startup’s public launch and long before its place on design tool Mt. Rushmore. “I went to Figma not because I thought it'd be a big business, but because they were building a magical tool that I loved,” he says.

Yamashita’s pipeline from passionate user to builder is a familiar story in the tech world — becoming so enchanted by a product that you set out to help build it yourself. These are often the folks who can help propel a startup from up-and-comer to generational company.

We’ve dedicated a substantial share of our digital pages here on The Review to the grueling 0 to 1 phase of product building, or put simply, finding product-market fit. But there’s no ribbon at the finish line once you’ve found it. The goalpost immediately moves to the next phase of growth, whether that’s expanding to new markets and users or launching new products — you’re now going 1 to 10. Yamashita has carved out a career dedicated to this messy middle stretch of a startup’s life: charting a path toward steady growth after nailing PMF and assembling a team to pull it off.

I have a worldview that not everything has to start from scratch. I'm more optimistic that I can take an existing product and evolve it, or radically change it, or extend it in really interesting ways.

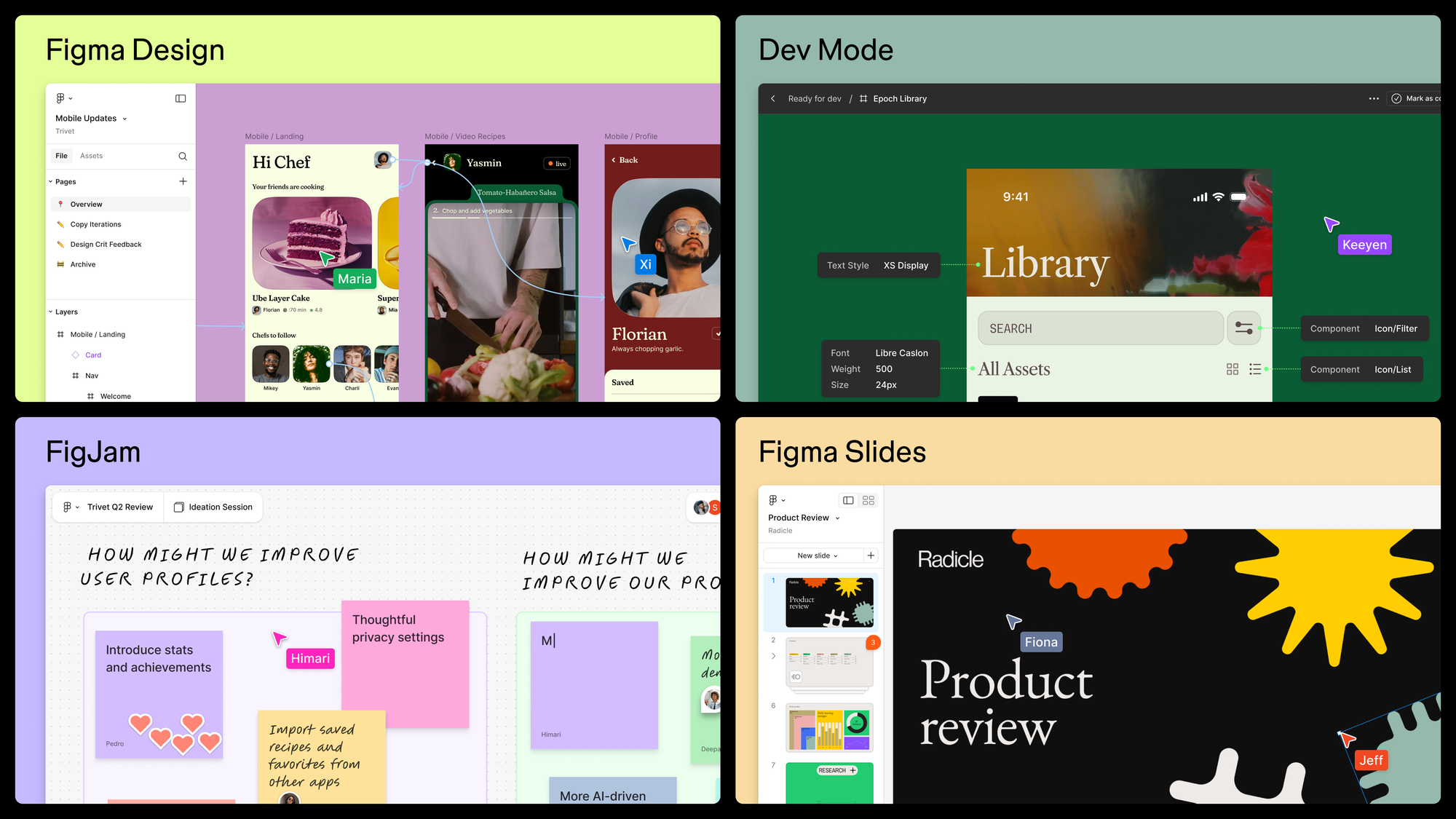

And Figma’s 1 to 10 product roadmap has been jam-packed under Yamashita’s direction: On top of core product iterations, the Figma team has rolled out countless features and new hits like FigJam, Dev Mode and, most recently, Figma Slides (for the detailed backstory on how Figma Slides came to be, check out our deep-dive with founding PM Mihika Kapoor).

In this exclusive interview, Yamashita walks through his three-phased approach to building and launching new products. He starts by sharing tactics behind idea generation and Figma’s successful expansion into different user personas, how he staffs the teams to build products that support these personas, and eventually, the core tenants for great launch storytelling (does your product pass “the screenshot test”?).

In the spirit of Figma, there’s something in here for everyone who leaves their fingerprints on a product — founders, engineers, marketers, designers — not just product folks.

Mining for ideas and bringing new user personas into the fold

Figma spent its first five years refining its core product for one primary audience: designers. Then over the next four years, the company was able to broaden its user profile, adding more product managers and engineers into the design file — both by launching new products, but also because the app was open and web-based. Interestingly, one-third of its users were developers before the company even launched Dev Mode.

“As we've embarked on the journey of becoming a multi-product company with FigJam, Dev Mode and Figma Slides, we’ve changed the way we work significantly,” says Yamashita. “We already knew how to talk to designers. But with new products, we had to figure out how to meet the needs of the entire product team. So we had to change the way we work, starting from who we talk to and how we communicate with them.”

Today, Figma has expanded beyond its core designer persona so successfully that non-designer users outnumber traditional designers. “Two-thirds of our weekly active users are now non-designers,” he says. “These new products that we've built have started to widen the aperture and optimize for our different audiences.”

Here’s how Figma tackled balancing new bets with the core product and speaking to new personas.

Watch how users are hacking your core product

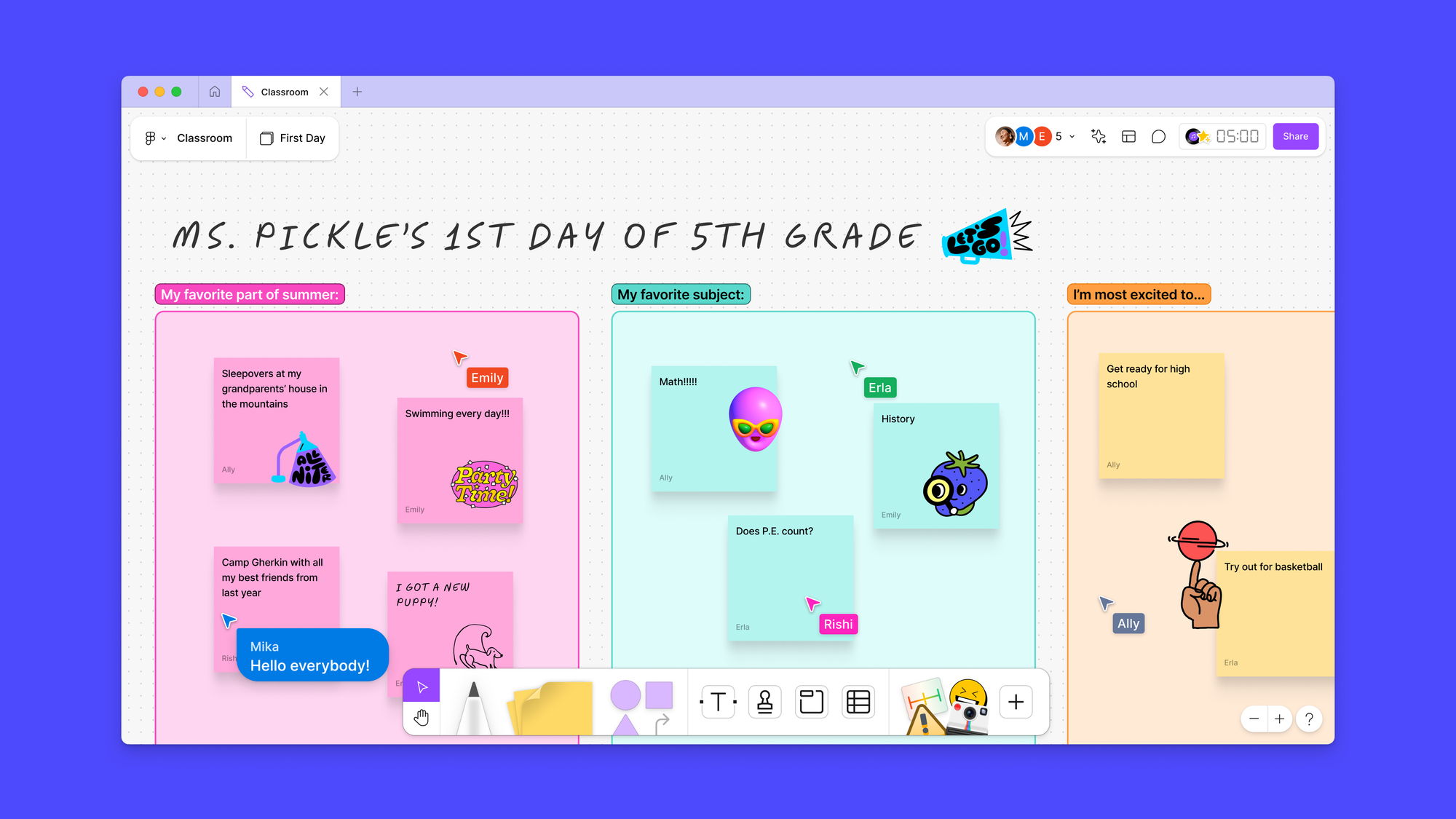

The inspiration for Figma’s second product, FigJam, came during the lonely days of lockdown in 2020, about a year after Yamashita joined the company as VP of Product.

“We noticed that people were using Figma design as a whiteboard and brainstorming tool. This was during the pandemic when everyone was working remotely and sick of Zoom happy hours. So people started hanging out in Figma instead,” Yamashita says.

The product team’s ears perked up. “We thought, ‘Okay, we should capitalize on this,’ because whenever your users are hacking your product in a fun way, that's really great inspiration,” he says.

But even if this was a compelling option for Figma’s second product, Yamashita knew not to rush to stamp the decision. The next product had to support the business and fit within the company’s larger goal. “A lot of people see Figma as a design tool where you draw some mocks and build some prototypes, but we know that’s not the end goal,” Yamashita says. “The broader goal is to actually get a product built and in users’ hands.” FigJam was a step toward that process.

After deciding to build the product, the team faced a classic fork in the multi-product roadmap: Carve out a new team to own FigJam and ship as fast as possible, or keep its development within the core team?

Internal debates centered on two factors: speed and creative divergence. For speed specifically, the team mulled over the state of their competition: “We were playing catch up. There were a lot of great players. Speed seemed of the essence,” says Yamashita. But speed comes at a cost. If you’re building quickly, it’s difficult to fully grasp how a second product might fit into the bigger picture. “The more we create divergence, the more difficult it becomes to unify later on,” he says.

The question sparked productive dialogues that informed Figma’s approach to future product rollouts. “Now, as we build our third and fourth products, we have more of a framework,” says Yamashita. “We know we should have a different way of organizing so that there's a team that's thinking about these shared primitives right out of the gate. But back then with FigJam, we were just kind of winging it.”

Build forums to let winning ideas (and their advocates) bubble up to the top

Yamashita says Figma’s leadership team is always on the hunt for hungry upstarts who can bring something new into being. “At Figma, we often talk about ‘starters,’ the people who are really great at getting something off the ground — people who can come up with a core idea that you can latch on to. So whether that's in engineering or design or PM, we definitely look for that skill set.”

Figma has created an internal forum to give grassroots ideas a platform: Maker Week, a hackathon that gives all employees the chance to pitch new projects. “People make everything from software to physical things that express themselves,” he says. “People often pitch new products, and you see who emerges as particularly entrepreneurial. It’s a forum that allows you to be experimental with these prototypes.”

So how do you spot those “starters”? Sometimes it’s brute force and hustle and scrappiness. Other times it’s the ability to sell the team on an idea. But in Yamashita’s view, starters all tend to share one trait. “I think entrepreneurs are slightly irrational,” he says. “By taking something from nothing and bringing it into existence, they’re doing something that people didn't really believe was possible. There’s a lot more brute force and selling that needs to happen.”

New products don’t emerge from a rational line of thinking.

The poster child of a Maker Week success story is Kapoor’s pitch for Figma Slides — who later presented her pitch to Yamashita in a product review.

Staffing up for a multi-product suite

Once you’ve got new bets locked into the roadmap, how do you start divvying up your roster of builders?

Yamashita’s experience with FigJam helped him outline a more intentional approach to assembling the team for Figma Slides and Dev Mode.

Chart the quickest path to prototype with a lean crew

Yamashita cautions against routing a ton of talent to tackle a hot new bet — instead suggesting that a dedicated few can get to work building a sample product.

“With new products, we always start pretty small,” says Yamashita. “We can do all the reviews that we want, but a working prototype can take an idea from something on paper to something that's actually believable.”

That was the case for Kapoor’s initiative to get Figma Slides onto the product roadmap — it was just her (a PM), an engineer, and a handful of other team members who she successfully pitched to work on a Maker Week demo. After that initial company-wide presentation, the small team was able to quickly scrap a prototype together so that decision makers (like Yamashita) could visualize the idea’s potential.

“We didn't give that green light to Mihika right away. But her small team persisted and she convinced some teams to start using it. And the next thing you know, it proliferated internally.”

A small prototype or MVP completely changes the game — when you see a surge of everyone wanting it internally, it gives you more conviction that there’s something there.

Bring in outsiders to deepen understanding of new users

When it comes to weaving new products into the core offering, Yamashita thinks that some disagreement among the product team is useful: “The best products come out of a bit of internal conflict, when people stand up for a use case in a way that’s counterintuitive to the core product team.”

When a core product team has built years of intuition around one set of users and one way of thinking, it can be hard to suddenly consider the needs of a completely different persona. Yamashita has found the internal debates that spring from these conversations to be productive.

This became clear when launching Figma’s third product, Dev Mode, to a user persona with a wholly unique set of needs: developers. “You look at our core product and you'd think that every new product has to create an infinite canvas. That's just table stakes at Figma, right? But it turned out that developers found a blank canvas really hard to navigate,” he says. “It was important to bring on people who could advocate for that perspective and challenge core assumptions — and through that debate, you build the best product.”

FigJam may have been a new product, but it was created by existing teammates for an existing persona. For Dev Mode, they decided to bring in external people who could build for developers, a completely new persona. These weren’t just any new hires — Figma acquired a company working on a Figma dev tool spinoff, Visly.

“For our developer efforts, our engineering leader, Emil, was someone who we found through an ‘acquihire’ of a team that was thinking about how to translate design into code. So they built their own tool because they didn’t think Figma was doing enough,” says Yamashita. “The fact that this company existed meant that Figma as it stood was not doing enough for developers. So they brought in an outsider's perspective, which was really healthy.”

To build new products, you need to create an environment where people can really feel ownership of their new audience without feeling the burden of legacy.

Launching new products: The two hallmarks of a compelling debut

Yamashita’s product launch strategy can be boiled down to one skill: storytelling. It’s a discipline he finds central to product building, and he credits his high school English teacher for nurturing that instinct.

“My high school English teacher taught me all about literary commentary, or reading something and making a case for what it’s about,” he recalls. “That’s so connected to product building because it’s all about storytelling. Why does this alliteration matter here, for example? This is an approach I take to product building — you have to take those little bits of insights to derive a thesis on why you need to build something.”

To double down on the English class inspiration, Yamashita contends that much of Figma’s multi-product success can be chalked up to great storytelling around the launch of each new bet.

Below are Yamashita’s tenets of great product launch storytelling, along with simple tests to run your own products through. He shares examples from Figma’s past launches, from how co-founder Dylan Field thoughtfully spun out the OG product to the design community to the storytelling magic behind recent launches like Dev Mode and Figma Slides. Spoiler alert: they’re not all that different from the ingredients of a great story, full stop.

Tension: The feather-ruffling test

Nothing gets a community talking like controversy. “Every good narrative has a little bit of tension,” says Yamashita.

Perhaps no Figma launch story sparked more online chatter than its original product. “Dylan wanted to get the design influencers on board, the people in the community whose voice mattered,” he says. “He kept going back to them, not trying to sell them on it, but just showing Figma to get them excited.”

Field understood that he wouldn’t be able to create any momentum if the product didn’t have a strong perspective on the way design teams should work. So he gave those influencers a somewhat controversial idea to talk about: Everyone could work in a design file at the same time. That got people talking.

The mark of a shrewd bet is, of course, the product’s eventual success — and Figma’s vision for collaboration ultimately created a new norm for the design process. “Now, it’s intuitive, but back then it was considered undesirable to have a hovering art director in your file. That your product manager or your CEO is going to be able to see every movement you're making wasn’t something that was necessarily welcomed, but it also had a view about design and what it should be that was more progressive.”

Figma’s balance of standing for what design should be while creating a little bit of controversy supplied a narrative that influencers and evangelists were excited to talk about.

Simplicity: The screenshot test

Yamashita has a simple litmus test to gauge the effectiveness of a product’s story: Can its value be distilled into one single, self-evident screenshot?

At Figma, visuals are just as important — if not more important — than words. “What’s the one screenshot that’s completely self-explanatory?” he asks. While he acknowledges this might be a “superficial” way of thinking, distilling the product’s story into a single screenshot or gif or tweet helps arrive at something evocative. “You need to show something people want. That’s a design problem. That’s a storytelling problem. That distillation is really important,” he says.

But this isn’t just a thought experiment to conduct the week before a launch. Preserving simplicity is an ethos that starts in the very earliest stages of product development, and Yamashita takes care to push his team to always whittle as much as possible. “When we’re in the process of designing a product and adding new features, it’s easy to just add more and more stuff,” says Yamashita.

This test is a useful way to push his team to simplify things further. “It forces people to think about simplicity, but it also forces people to think about brand as well. Because the best stories make you feel something.”

If you’ve been involved in the evolution of the product, you can empathize with how you got there. But users don't see that evolution — they’re coming fresh at a screenshot with no context. If you have to explain what's going on, that's an indication that you haven’t made the value proposition simple enough.

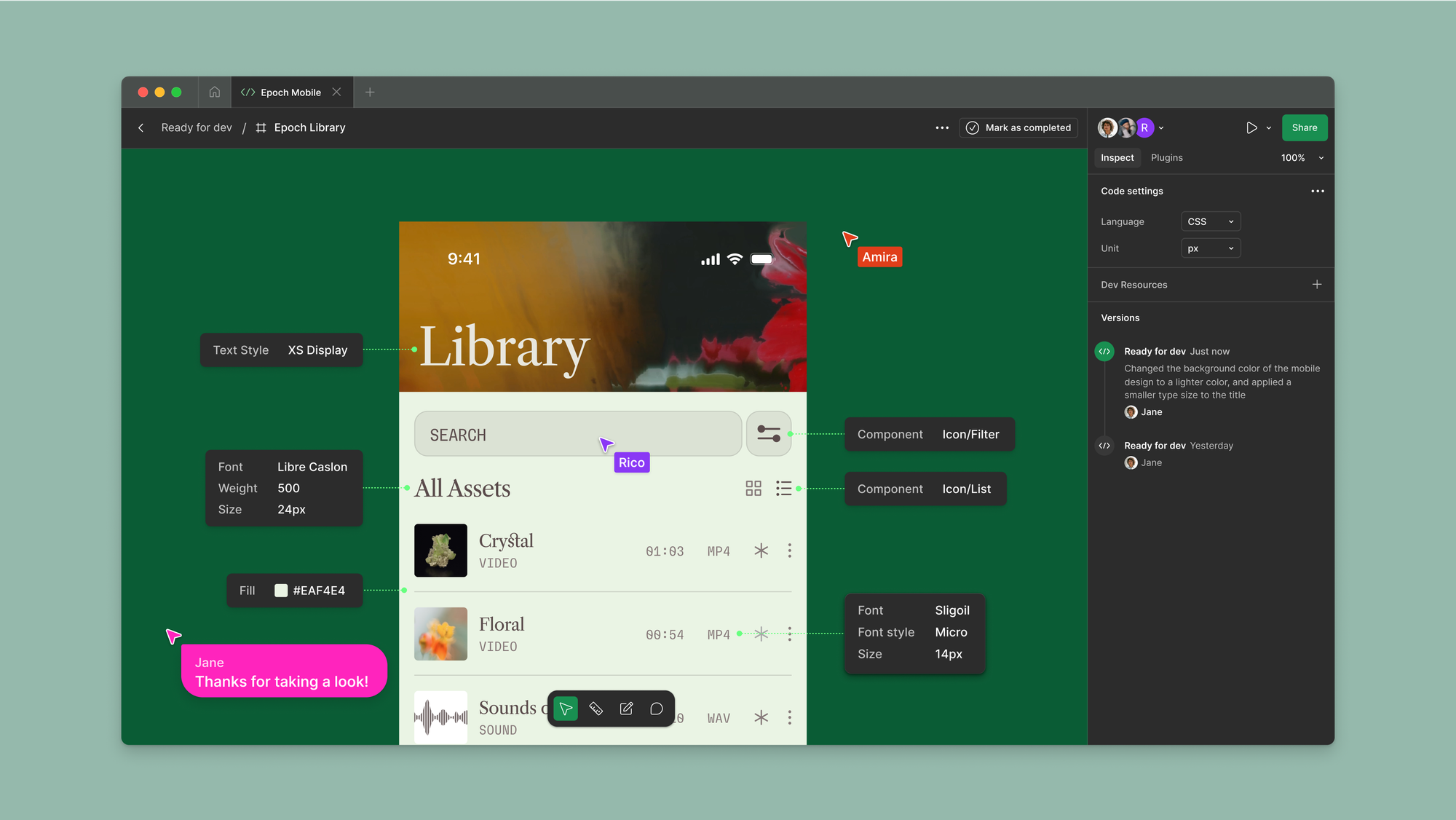

Yamashita points to the launch of Figma’s Dev Mode, which gives designers and developers the ability to work in different modes in the same Figma files. A single screenshot packed a punch in luring a new persona to the Figma suite: developers.

“For Dev Mode, we used screenshots to show how developers can have a diff in their designs with a green and red view that they see in code all the time,” he says. “To be able to see designs with code underneath is really evocative, because now developers will think, ‘Oh, now you’re speaking my language.’”

Don't let expansion compromise simplicity

As Figma has grown into a multi-product shop, Yamashita and the team remain dedicated to product usability. The products are so usable, in fact, that third graders can find their way around Figma Design, FigJam, and Figma Slides. “We have a big education investment right now, and I was recently watching third graders in Japan use Figma,” says Yamashita.

But watching children use the tool for social studies was a stark reminder for Yamashita that every new user today needs to find Figma products just as intuitive as the Figma that launched almost a decade ago. “Simplicity shouldn’t be equated with fewer features. It’s about mental models. When you look at a really complicated product, you’re like, ‘I’m trying to do this thing. I know it’s somewhere, but I have no idea how to get there.”

The 1 to 10 product journey is a constant balancing act of building for new use cases while preserving simplicity. “Products only get more complex over time. You still need to pass the screenshot test — you can look at it and quickly parse what’s going on. The design should tell you what to focus on. The best product managers can push for that.”