For a moment, simplify the purpose of startup to one act: the transfer of belief. From founder to herself. From founder to startup. From startup to investor. From startup to market. That last transfer of conviction proves to be one of the most tenuous. According to a three-year study on startup mortality, most startups fail after having raised $1.3 million and around 20 months after their last financing round. Of course, many factors contribute to those failures, but it goes to show how treacherous of a stretch it can be for startups seeking to pave a path to market.

What’s needed is a simple test that can bring a go-to-market strategy into focus — one that can help startups smartly deploy limited resources when a product is first launched and a company has one chance to make a strong, first impression. For these inflection points, startups need a compass, and in my decades of working with them, I think this framework points them in the right direction.

The Framework And Its Two Forces

In 2003, a handful of fellow professors and I started lobbying Stanford Graduate School of Business (GSB) to develop a new sales course. The goal of the course would not be geared toward individual salespeople, but how an executive can position a startup to take a product to market. Out of all the professors, the head of the marketing department met me with equal enthusiasm. We locked ourselves away and started designing a course. But, we represented two different domains — marketing and sales — and so we started by asking ourselves: “What’s the difference between marketing and sales? Why would Stanford GSB teach both?”

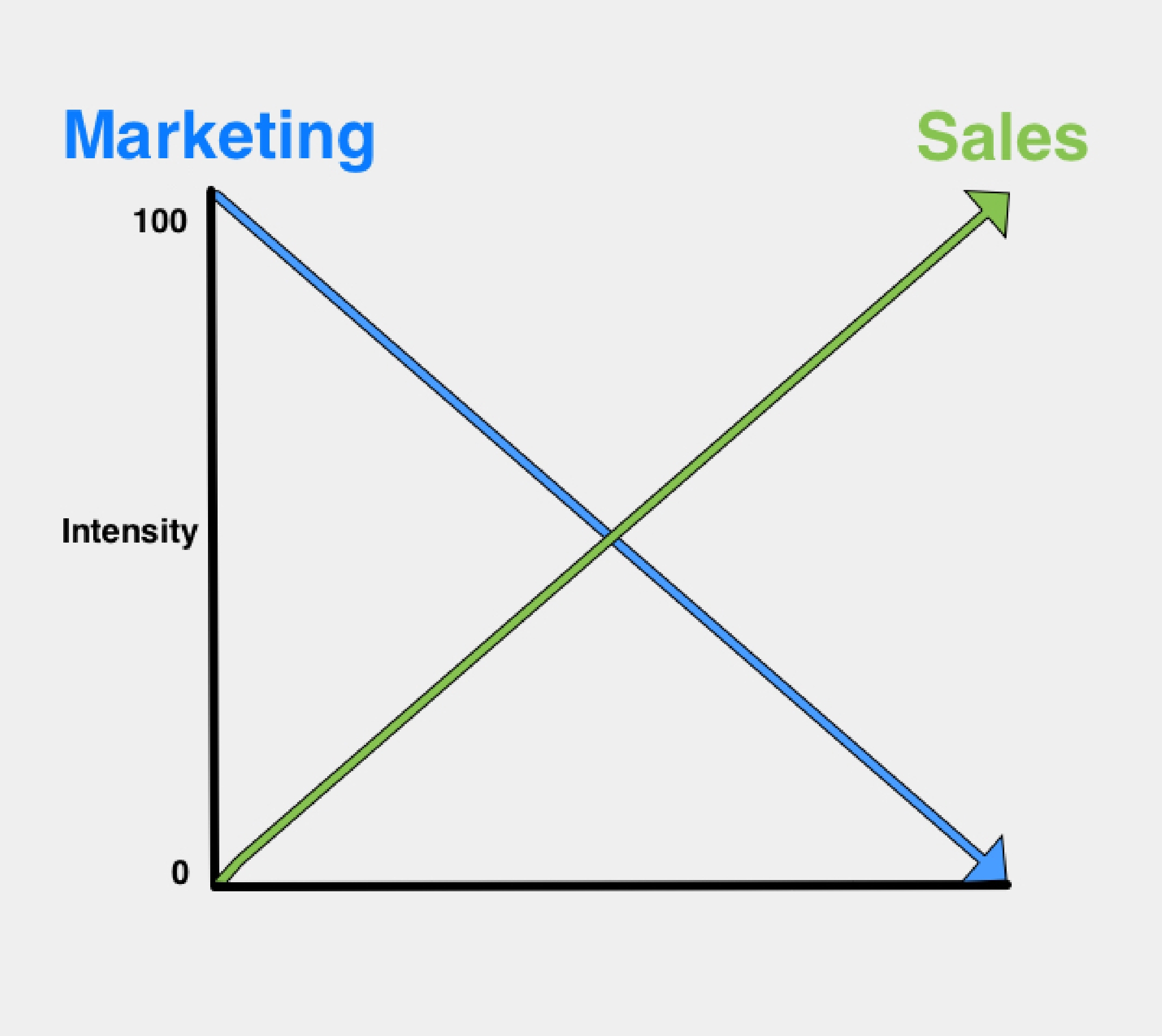

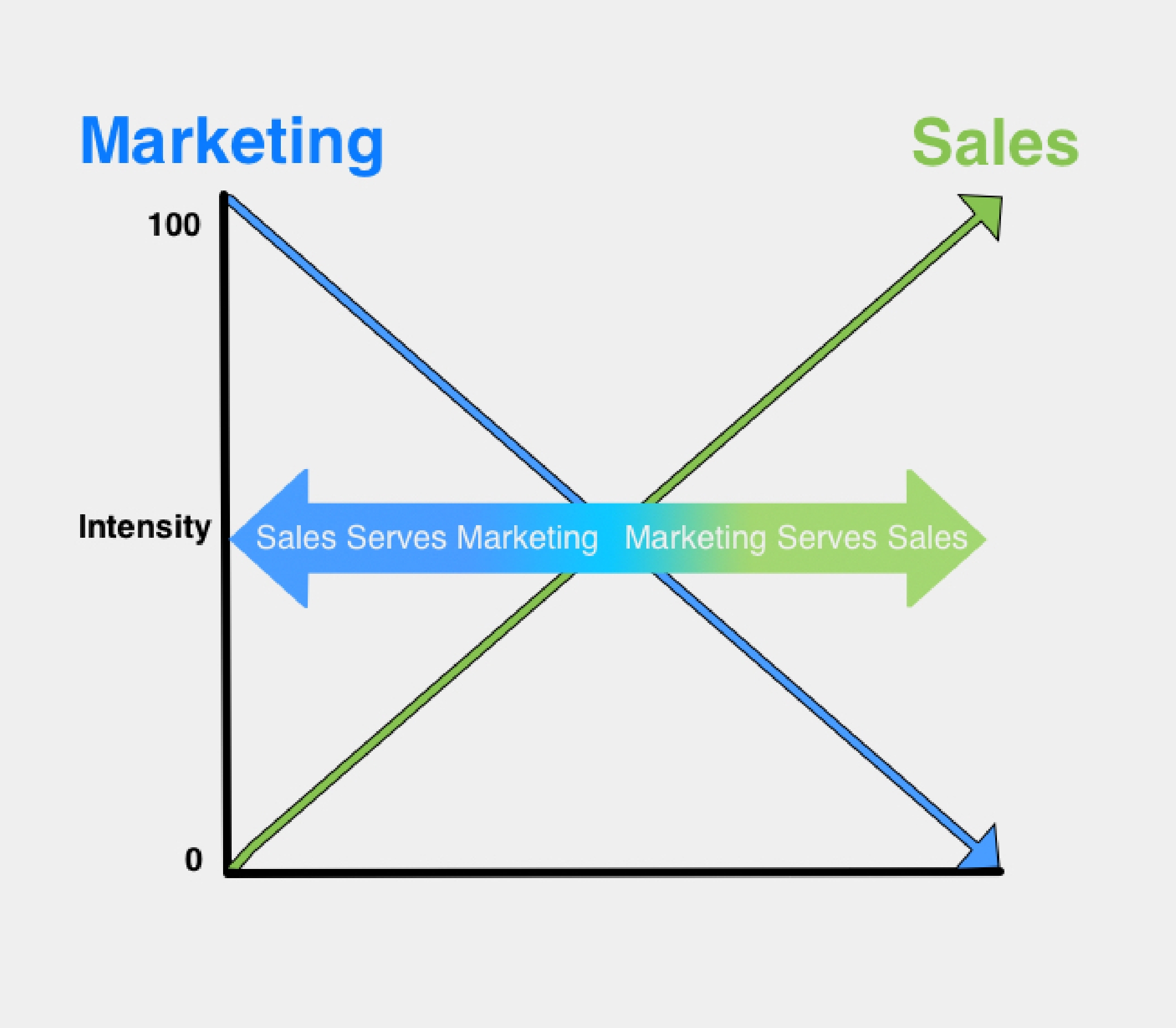

To answer, we went up to the board and drew a diagram like this:

This conceptual framework exhibits the interplay between sales and marketing in a go-to-market strategy. When a product has been commercialized and is available to the public, a company has two key muscles it can flex to take it to market: marketing and sales. Most companies that get this far know this intuitively. But what this chart suggests is that marketing and sales are counterbalances. The less marketing is flexed to bring a product to market, the more sales must step in. If sales is not driving the go-to-market strategy, the more marketing must. In nearly every case, either marketing or sales takes the lead in getting the product to customers.

The challenge is in knowing which one to activate for your company and specific product. This answer is especially critical for startups, which all too often pour resources into both to eliminate the guesswork, even though this wastes a great deal of resources. The stakes are high. If they choose the wrong path, they can stumble out of the gates. For example, hiring a high-touch, expensive sales force to sell a low-priced product can be a game-ender. After this misstep, an otherwise high-potential company may fail to grow fast enough to compete or reach profitability.

So, at the heart of the framework — and a startup’s go-to-market strategy — is this question:

Is your product marketing-intensive or sales-intensive?

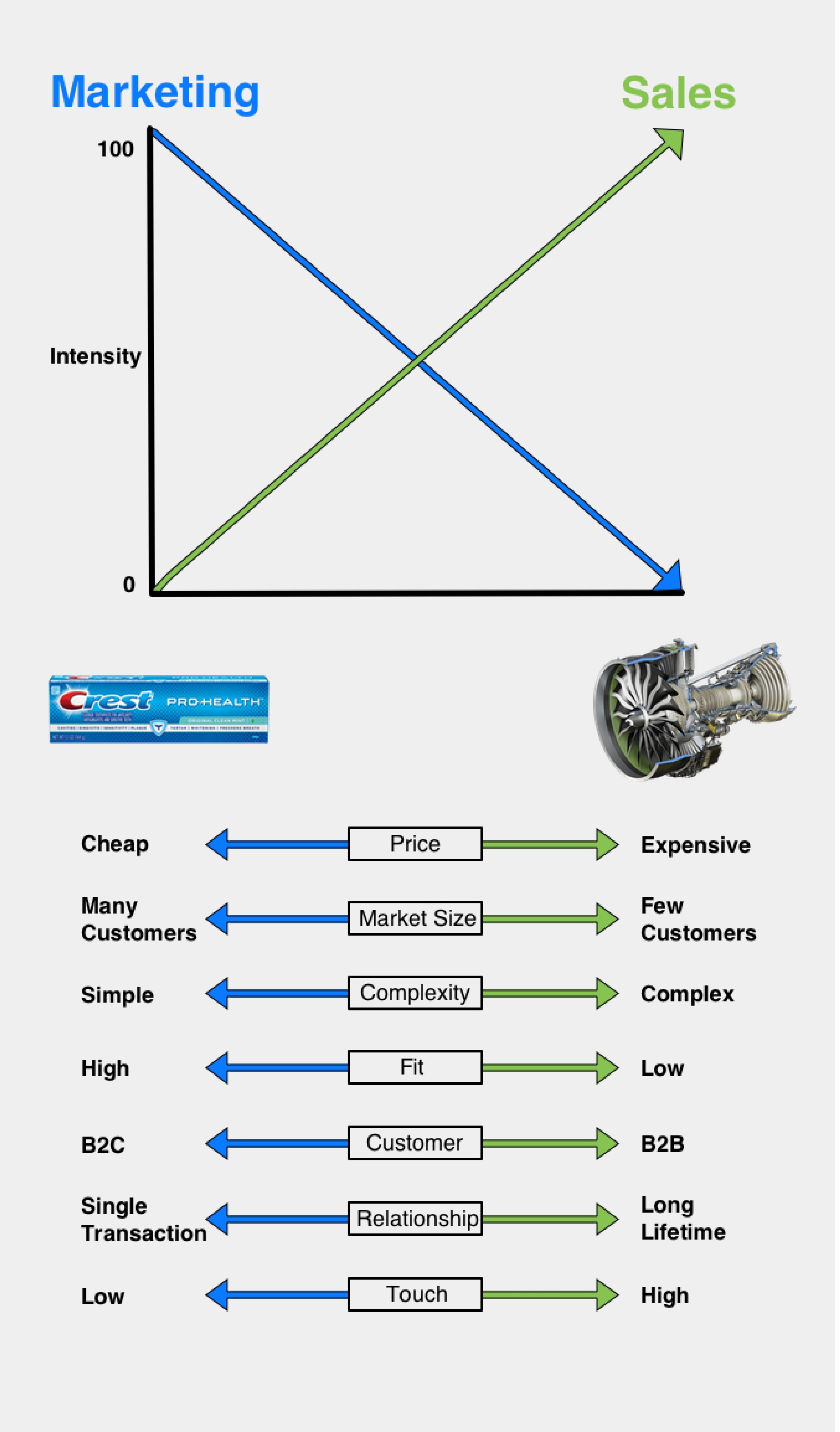

To better answer that question, let us examine two extreme examples — Proctor and Gamble’s Crest toothpaste and General Electric’s jet engines — to illustrate the framework. Key to this chart is the x-axis, which has multiple variables to consider that are crucial — but not exhaustive — in hashing out how you should go to market.

The first step for startups to take is to determine where they lie on the spectrum by examining the variables. Examine each one and determine whether your product lies on the left (marketing-intensive) or right (sales-intensive). To determine the answer, ask yourself the following questions about each variable. Let’s continue with toothpastes and jet engines, to illustrate the framework:

Price is determined by how the customer values the product or service. Simply stated, it’s how much is the customer willing to pay, which is tied to the return-on-investment that the customer realizes. For example, you can’t afford to “sell” a $2 tube of toothpaste. To prove it, just take the total cost of the salesman and divide it by the number of sales calls in a year. That’s why no one goes door-to-door saying, “Let me explain the benefits of Crest over Colgate.” But, say you’ve got a product that costs $100,000 to build, you need to sell it for $200,000. Now you’re in a sales-intensive go-to-market strategy.

- Ask yourself: Is this a large or small economic decision for the buyer?

Market size is determined by the quantity of potential customers. Products may be saleable to millions or even billions of customers (via smartphones), or only to a very few. For example, billions of people need toothpaste, but unlikely more than 100 airframe manufacturers are in search of a supplier of jet engines.

VERITAS’ original product was an operating system component that the company sold to systems manufacturers as part of their UNIX operating system. When VERITAS went to market, there were many who wanted to spend money on marketing. But Leslie felt differently. At that time, there were roughly 100 system manufacturers, so spending money on ads or mailing lists didn’t make sense. Instead the company invested in going to industry shows — but never bought booths. They knew who the customers were, so sought them out, rather than waiting.

- Ask yourself: Is it easier for them to find you or for you to find them?

When it comes to the level of complexity, some products are dead simple, while others require education, manuals and customization to derive utility. From turbines to subsonic inlets, jet engines are composed of countless components, whereas operating a tube of toothpaste is completely self-evident.

Another example is Oracle ERP, which can take hundreds of people years to implement. As a complex product, it’s always sold, never marketed. Whereas Uber is supremely simple for the consumer. We all remember the first time we opened the app, figured out how to call an Uber and then a little car appeared on the map.

- Ask yourself: Can a customer self-serve to use or is education required?

Fit and finish ranges from out-of-the box solutions to something that requires multiple steps or points of support to operate. As toothpaste literally comes out of the box — or tube — it has a high fit and finish. However, when a jet engine is purchased, that’s just the start; it has to interact and interface with other parts of the plane. However, don’t mistake complexity with fit and finish — some products that are highly complex have a high fit and finish. For example, a Tesla — or any new car for that matter — has hundreds of computers, but you just need to turn your key or press a button to start it. Regardless fit and finish is key. In most cases, poor fit and finish only has longevity when the customer has no better alternative.

- Ask yourself: After all is designed, done and shipped, is there still much more for the consumer to do?

Identifying whether you’re serving a business or consumer is a big component to a go-to-market strategy. Products are sold to businesses or directly to consumers. Each requires its own type of relationship. But it’s key to note that this is a volume metric. There are more consumers than businesses, and the former is more homogeneous than the latter. The vast majority of people need toothpaste, but the vast minority of businesses do not need a jet engine.

- Ask yourself: Am I predominately selling directly to people or companies?

The customer economic lifetime focuses on the cadence and duration of interaction with the customer. Though there is the issue of brand loyalty, there will be hundreds of tubes of toothpaste bought by a customer over her lifetime. Given that jet engines last many years and that there are roughly 100 manufacturers, there are no more than that many deals a year — and likely much fewer. The question is the nature of the relationship with the customer. Do you expect to have a long-term relationship with increasing revenue over time, or more transactions with increasing frequency over time? The longer the lifetime of the relationship, the more consideration goes into how I actually deliver and sell this product.

- Ask yourself: Do I measure successful customer relationships by transactions or longevity?

Linked with the customer economic lifetime is whether a product requires high-touch or low-touch selling. Selling jet engines often requires a “design win,” a very long, complex, technical campaign that results in many sales over the years-long lifetime of a particular model. It requires relationship-building and may be worth billions of dollars over twenty or thirty years. Low-touch sales don’t require the ability to ‘land and expand’ or customize sales according to the relationship. It takes little history to buy the same or different toothpaste.

- Ask yourself: How much agency do you have in developing your relationship with your customer? Can your efforts compound or are the mostly one-off?

In summary, Crest is the extreme example of a marketing-intensive product: it’s very low cost, bought by millions of consumers, simple to operate and has a high “fit and finish” as it’s ready to use immediately after purchase. Though P&G would like to have lifetime customers for its toothpaste, it has a very low switching cost and a purchase decision can be influenced by a coupon. Have you ever met a P&G sales representative who has extolled the virtues of Crest versus Colgate?

On the other hand, the General Electric jet engine typifies the sales-intensive product. The engine’s price tag is in the millions of dollars, is sold to about 100 airplane manufacturers, has incredibly complicated technology and has low fit and finish, as it always requires extensive engineering and customization after the sale. It’s the ultimate selling experience because it’s a design win. A customer wants fuel efficiency, strict weight thresholds, thrust, a certain level of noise and hundreds of other specifications. Jet engine manufacturers spend a long time on not only building the products, but defining and fulfilling contracts — it’s very high touch. For all these reasons, I’ve never seen a GE jet engine offered for sale at Walmart.

Finding Your Mark

As a conceptual framework, the key is less to identify your company’s exact point on the spectrum, but more to know which approach (or in which half of the diagram) your startup is positioned. Depending on whether your new product is more like Crest toothpaste or a GE jet engine will help inform if your go-to-market strategy should be more marketing-intensive or sales-intensive.

If you’re marketing-intensive, the product is bought. If it’s sales-intensive, the product is sold.

There are exceptions, but, by and large, how successful a go-to-market strategy depends on how reasonably aligned each factor is in the same half of the diagram. Here are two companies’ stories that illustrate the importance of alignment:

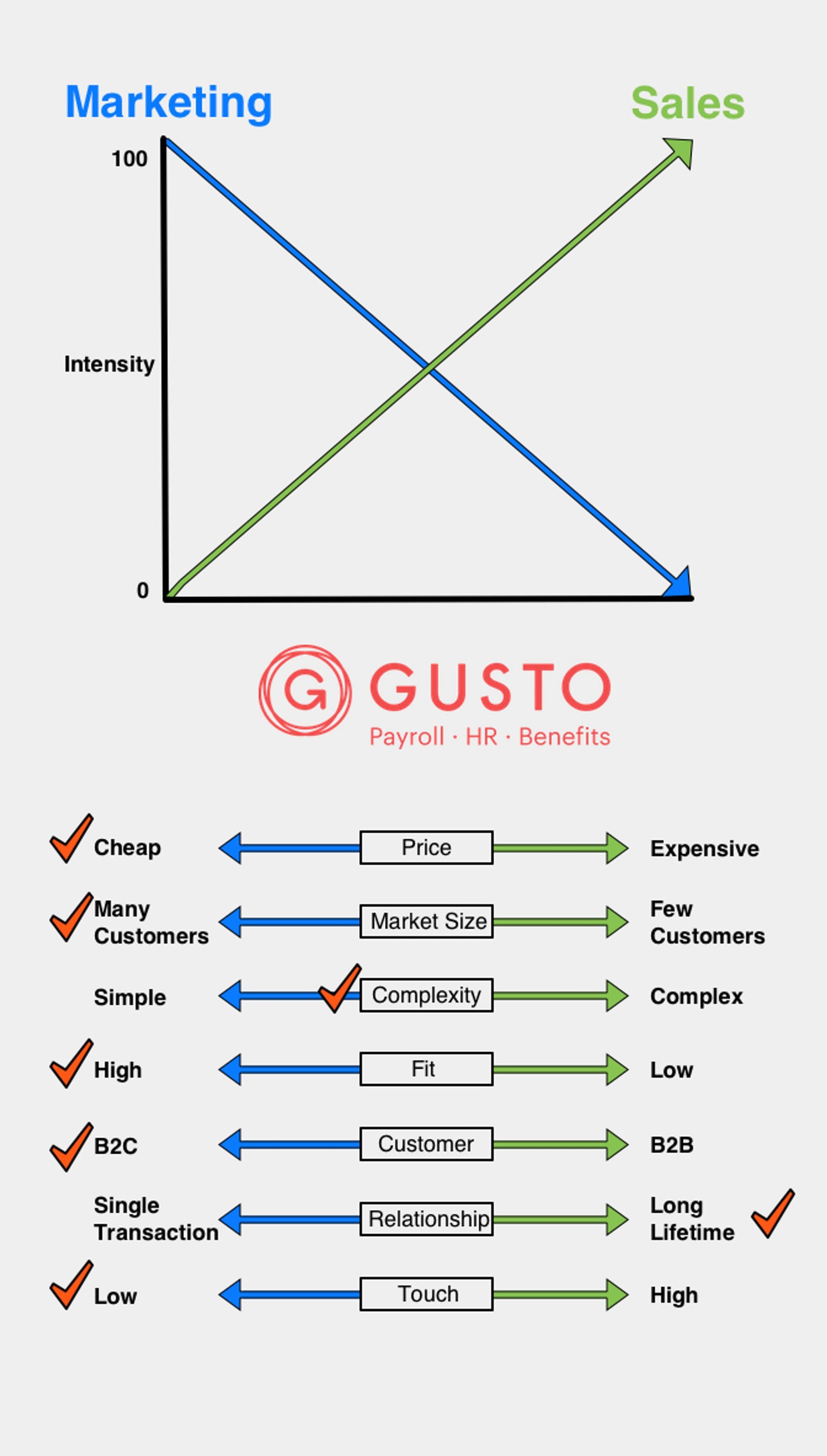

Online HR services startup Gusto is an example of good alignment, which led to a successful go-to-market strategy. Gusto — formerly known as Zenpayroll — operates in a market where tools to run payroll are built for bigger companies, involve heavy duty interfaces and require a bit of a learning curve or support team to troubleshoot.

When Gusto decided to offer a solution to many, tiny companies, it had to alter other aspects of how it would go to market. For example, it decided to take a low-touch approach and sell its services over the web. While its product is of medium complexity, it has extremely high fit and finish, as it takes only a few minutes to set-up and is intuitive to use. Relative to its competitors, its price is low at around $40 per month base price with a nominal per employee fee tacked on. It’s technically a B2B company, but where the second ‘B’ is more like a ‘C’ given its many, smaller customers.

Today, Gusto now has about 50,000 customers. Here’s what its chart looks like:

It’s important to note that not every checkmark needs to be on one side of the chart for a successful go-to-market strategy to unfold. However, startups must be aware of the points of misalignment to make adjustments, as Gusto did adjusting its B2B business to a B2C approach given its many, smaller-sized customers at the start.

In contrast, a cautionary tale is the story of private cloud computing startup Nebula. It seemed to have it all, at least on paper. A co-founder who helped start OpenStack. A leadership team that included the man who helped invent the first browser and a former Dell executive. This luminary founding had attracted NASA engineers and backing from top-tier investors.

After jumping out of the gates with big name customers — such as DreamWorks, Sony and Genentech — and about $1 million in sales the first quarter, the momentum slowed. Nebula hoped and planned for many customers, but, with a $275,000 starter kit, they had a relatively expensive entry-level price tag for customers to sign up without a long and arduous sales cycle.

Amid the then-emerging private cloud computing market and the highly anticipated Openstack movement, potential customers looked for a solution that was as plug-and-play as Amazon’s public cloud offering. Nebula launched as an “all-in-one appliance.” After its early go-to-market efforts the company realized that its solution required a high level of selling, service, support and education than any off-the-shelf product could provide.

Nebula’s sales team targeted businesses, but the product wasn’t entirely designed for them. For example, its servers’ exotic console — which even displayed Klingon characters — and touchscreen display were intended to excite the technorati. But serious business computing users tucked away servers in dark data centers where few people interacted with the product.

Lastly, when Nebula launched, it expected the plug-in-play solution would not require a high touch, but due to defensive moves by VMWare and the ease-of-use from AWS, Nebula’s sales pitch lost its punch and needed to be ever more personalized and niche to get traction.

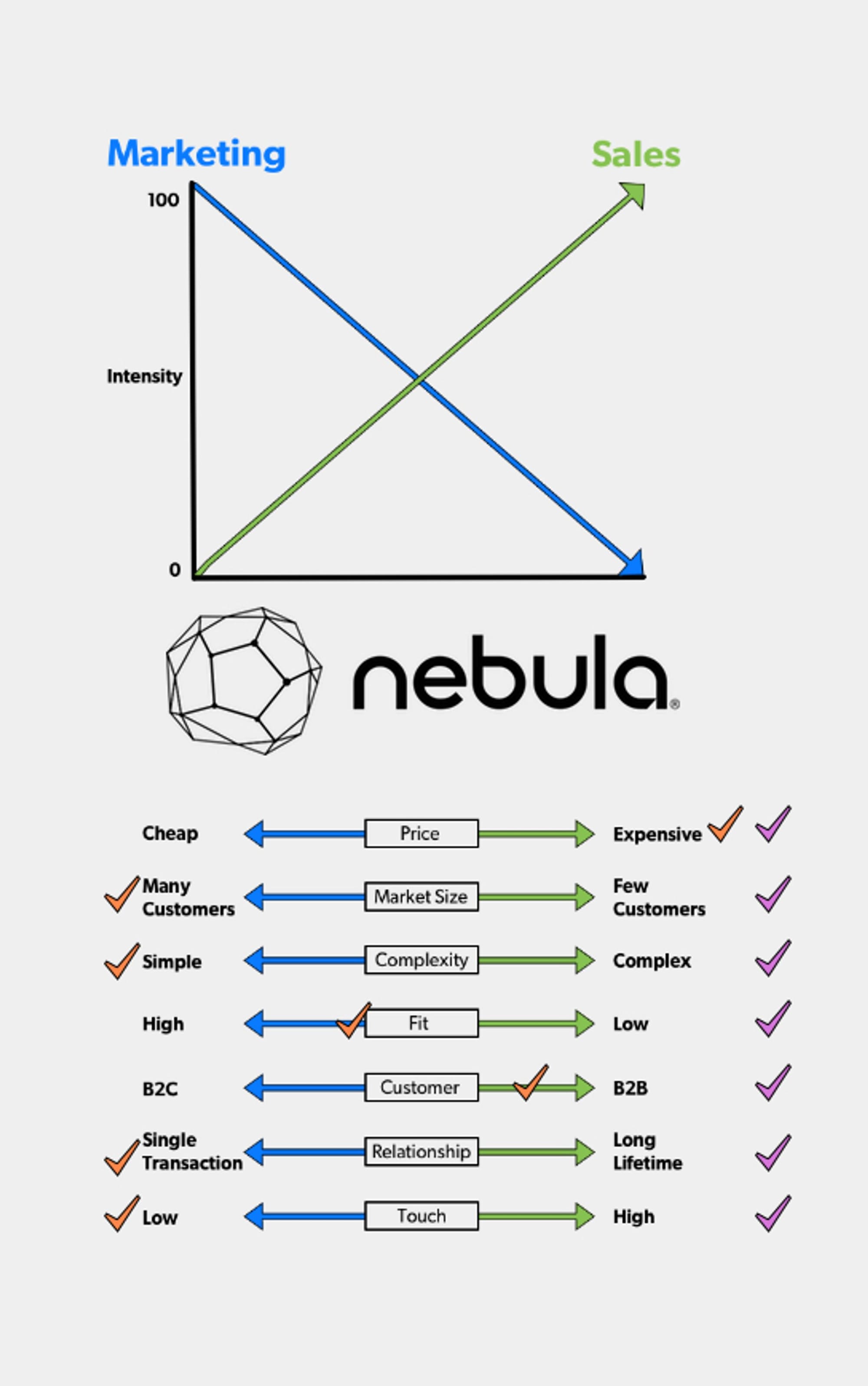

Nebula never hit its speed and shut down four years after it launched. Here’s what it’s chart looked like when it launched (orange checkmarks) and what, in retrospect, it should have been (purple checkmarks) as it planned to launch, according to Leslie.

Determine Whether Marketing or Sales Takes the Lead

To work through this conceptual framework is not only to increase the likelihood of a more successful go-to-market strategy, but also to determine how to best structure the relationship between sales and marketing to maintain that momentum.

The way to build on an effective go-to-market strategy is to know whether marketing or sales is taking the lead. If the answers to your questions in your framework — on price, market size, complexity and the others — align toward the left of the chart, marketing should take the lead with the go-to-market strategy. If the vast majority of the answers align on the right side, sales should take the lead.

Sales Serves Marketing

In the scenario on the left, marketing has primacy. In this case, marketing generates the demand. With its campaigns, it creates a strong enough appetite that people buy the product on their own. Sales serves this effort by creating a “place.” What this means is that they line up distributors, retailers and merchandiser so the product has a presence — essentially a place where it can be found and is available for purchase. Taking it back to the toothpaste/jet engine spectrum, examine the culture of marketing-driven Proctor and Gamble. One of the most highly valued jobs — with the greatest upward mobility — is the product manager, who works on the brand, advertising, PR, launch and more.

Marketing Serves Sales

In the scenario on the right, sales has primacy. In this mode, marketing’s responsibility is to create and hand off qualified leads to the sales organization. They manage various lead sources through an organized pipeline structure. They provide the collateral materials and programs to find prospects. The heart of the organization's success is for the sales department to convert a qualified lead to a customer win.

How Primacy Shifts

It’s key to note that at the as a company is placed on these axes, the level of primacy — for Marketing or Sales — is most intense at the left and right extreme positions, respectively. As you move toward the middle, the phenomenon of “serving” declines. At the midline, marketing and sales relate as equals.

Bringing It All Together

Understanding your go-to-market strategy as a function of the primacy of sales or marketing is paramount. Use this simple framework to establish whether you have a sales-intensive or marketing-intensive product that you’re bringing to market. Make that determination by pinpointing where your product stands on seven key variables: price, market size, complexity of technology, fit and finish, type of customer, customer lifetime and level of customer engagement. The framework provides a key question to help ascertain where a product stands on each vector, but is more geared to help startups understand whether they are all aligned. If so, not only will that make for a smoother go-to-market strategy, but also help marketing and sales better coordinate their efforts to win customers.

It doesn’t matter if you’re making toothpaste or jet engines — or anything in between. Any product can be bought or sold with the right alignment and team structure to support it. The questions this framework asks gets to the heart of building great companies and roll up to the most central question: What are we building and for whom? These questions must be asked and answered to be effective for a successful go-to-market. Of course, there’s no one framework that will guarantee victory, but, as the compass needle moves, this one will get you company pointed in the right direction. And that’s a competitive advantage in itself.

Mark Leslie is a Lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business where he teaches courses in Entrepreneurship, Ethics and Sales Organization. He is also the managing director of Leslie Ventures, a private investment company, and serves on the boards of two public companies, six private companies, and three nonprofit organizations. Prior, Leslie was the founding Chairman and CEO of VERITAS Software. He tweets at @mleslie45.

Matt Heiman, a former student of Mark Leslie at Stanford GSB and investment professional at Greylock Partners, contributed to this article.