Imagine you asked your finance team about how money enters and moves through your company, and they couldn’t tell you exactly where each dollar goes and is spent. You’d probably fire them all. So why aren’t a company’s users held to the same standard? Wealthfront VP of Growth Andy Johns receives a surprising number of blank stares and head scratches to this question.

Johns has spent his career helping startups grow. He’s been a product manager and internet marketer at Facebook, Twitter and Quora, where he worked on growing their number of active users. Johns has deployed more than $10 million in online advertising spend, built email systems that sent over 50 million emails monthly and executed over 400 product A/B tests for user acquisition and retention. Simply put, he’s the renaissance man of growth.

At First Round’s recent CEO Summit, Johns set out to help startups elevate their growth teams, via advice on hiring an exceptional head of growth and by helping founders sharpen their own growth chops. He mapped out what growth entails, outlined the three mandatory skills needed to be exceptional at it, and provided one-off lessons from his years in the field.

What a Growth Team Actually Does

“Do I really need this growth thing?” Four years ago, that inquiry was the most frequent question Johns received as he advised various companies on their growth initiatives. “Granted, the concept of a team dedicated to growth was still pretty new. Most startups saw growth as a company-wide objective and a bit of everyone’s role and responsibility,” says Johns. “Here’s the conundrum. Startups will build a really robust finance organization, but not a team with the responsibility to measure, understand and improve the flow of users in and out of the product and business. That’s the role of growth within a company.”

Finance owns the flow of cash in and out of a company. Growth owns the flow of customers in and out of a product.

In short, Johns believes that startups who have an established finance group but a fledgling — or non-existent — growth team have put the cart before the horse. “A finance team by definition measures, understands and improves the flow of capital in and out of a business. That’s important because it contributes to all sorts of incredibly important business decisions, from new hires to equity schedules, and from salary adjustments to office upgrades,” he says. “Finance uses its knowledge to help the business operate. What’s interesting is every company — and certainly the finance team — eventually realizes that the single biggest lever that it has for maximizing revenue potential is the number of users.”

Over the last four years, Johns has noted a shift in the line of questioning around growth. Now the most common question he gets is less about the necessity of a growth team and more geared towards how to hire someone exceptional to lead the charge. “Founders wanting to accelerate their high organic growth should bring a leader to take full ownership of it. In order to find someone great, you need to be able to determine if they can go beyond the basics,” he says. “To start, can they articulate the role of growth, and how it fits into the business? Can they go beyond the superficial explanation of growth as just measuring and testing stuff? There’s a skillset that they should be able to demonstrate when digging into these questions.”

The Three Mandatory Skills of a Growth Leader

Over the years, Johns has identified three key abilities that are pivotal to any member of a growth team and compulsory for its leader to master. Here are those skills and a basic line of inquiry to discover if a candidate possesses them:

- Building growth models. Ask them how they’d build a model for your company’s main product to grow at scale. It can be basic, but should capture the core levers that explains how your company will grow (versus say, Facebook, Quora or Twitter).

- Developing experimentation models. Dig into how they’ve built testing and experimentation programs in a company. How have they organized a product design and engineering team around a testing schedule? Ask them to identify which experiments are most important and justify why.

- Building customer acquisition channels. Can they identify, test and scale new customer acquisition channels? How do they choose from and cultivate different parts of the funnel?

Depending on the seniority of your growth hire, you’ll need a candidate who has a combination of these tools at her disposal. “If you’re hiring a leader of growth at the executive level, you need to show excellence in at least two of the three categories. If you find a candidate that’s a master of all three, you’ve got someone special,” says Johns. “For non-executive growth hires, they should show expertise in one and strong promise in the others.”

To truly gauge their answers — and grow your company — it’s important to know some basic growth frameworks. Here’s Johns’ deep dive into these three growth skillsets:

Know your Basic Growth Equation

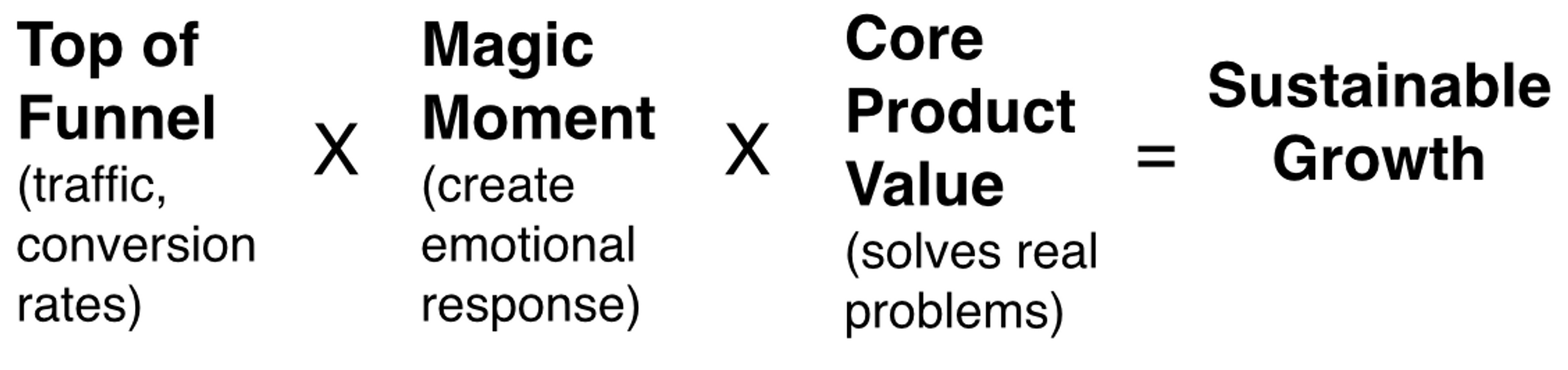

There are countless and complex growth models out there, but Johns recommends internalizing one specific equation. Here it is:

Johns learned this basic growth equation from his former boss, Chamath Palihapitiya, who ran growth at Facebook and now leads Social Capital. “Chamath uses this equation at the highest level to assess whether a product or a business has the ability to grow at scale for an extended period of time, through organic growth almost entirely,” says Johns. “In thinking about the products that I work on everyday, I can say that I follow this equation religiously.”

Here’s Johns’ breakdown of the three components:

- Top of the Funnel: In looking for a robust top of the funnel, what is being asked is: can the product capture traffic and convert it at an increasingly higher rate into some meaningful type of usage? This is a more tactical variable and the least important parameter in the equation, according to Johns.

- Magic Moment: This is the user’s emotional response when interacting with the product. Ideally, it strikes early and often in the product experience. “We have these moments with Wealthfront. One day, I went to bed and woke up to see it had harvested $3,000 in losses for me while I slept. It didn’t ask me to do anything or charge me; it just did it. That’s when I realized two things: One, how cool that I’ll have more money left over at year’s end and, two, I have to work on this product! That’s how investing should be.”

- Core Product Value: This component involves the size of your market, the legitimacy of the problem you solve and how right you were with your product/market fit hypothesis. For products that get the “magic moment” and “core product value” right, the top of the funnel naturally and rapidly fills. And when you have tremendous top-of-the-funnel growth you don’t have to fight to fill it. You just need to remove friction where it exists.

You’ve got a magic moment when how you frame what you do evolves from "I work on this" to "I get to work on this."

This equation is a fundamental starting point for any conversation about growth — whether it’s to evaluate products or test the understanding and acumen of a potential hire. “So when you’re chatting with a head of growth candidate, ask her about her frameworks for evaluating growth in companies,” says Johns. “She should at least be able to start with that growth equation, and ideally dig deeper to show a degree of thoughtfulness that you haven’t even considered yet. Have her mock it up on a whiteboard and verbalize it. Both are necessary skills.”

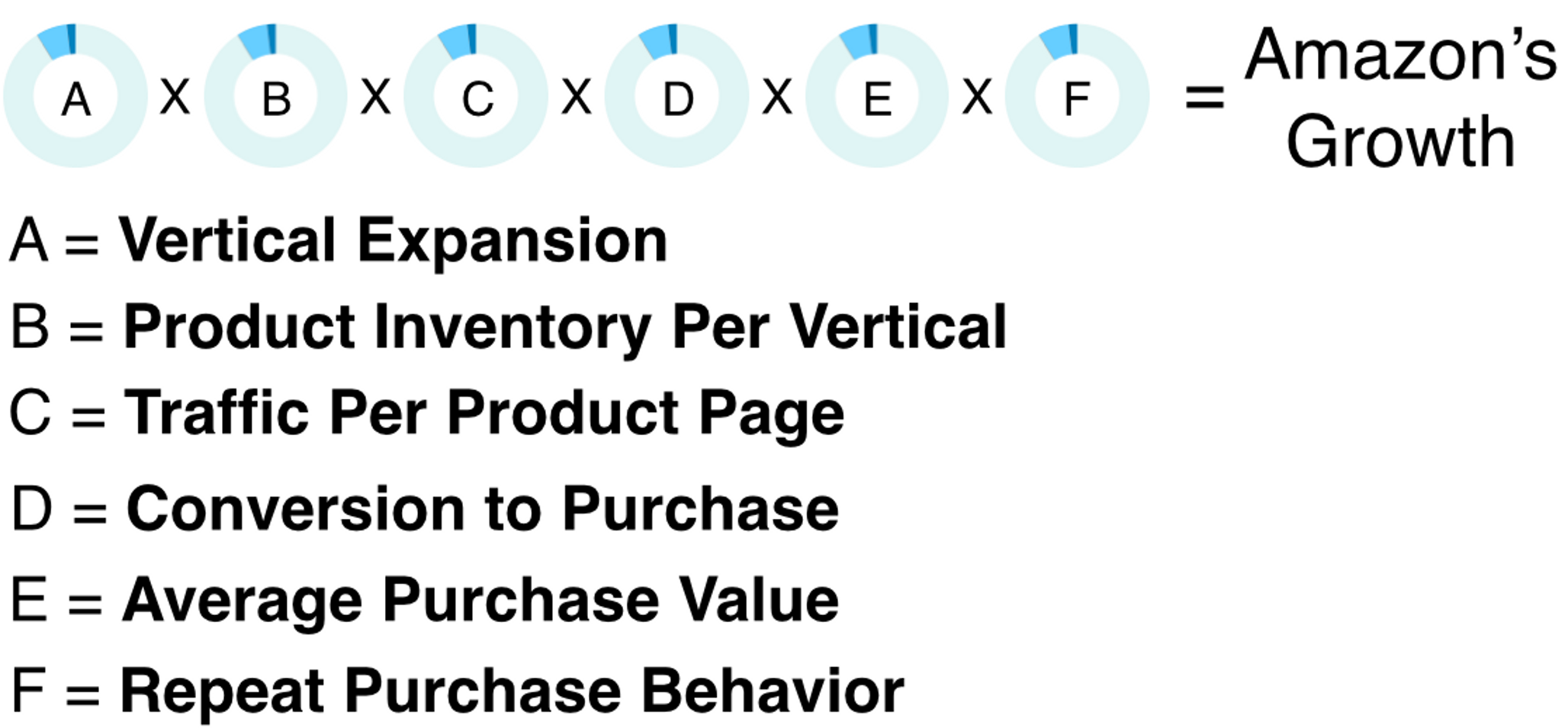

When he asks a candidate to list the growth equation for Wealthfront, the exercise reveals their training and instincts. “I can tell what they’re pulling from experience, what they’re drawing from their research and how they integrate information they’ve picked up from our interview,” he says. “All of those sources amass to show how they capture the main dynamics around our growth engine. At times, I’ll use Amazon as an example of applying the equation in an exercise.”

Johns’ growth model for Amazon provides an example of how to apply the basic growth equation to a real company. Here’s how he explains it — and would expect a head of growth to describe it:

- Vertical expansion. “When Amazon launched, it sold books. It’s growth was limited by books as a vertical. As it moved into more verticals, such as music or jewelry, it unlocked additional, latent growth potential and could expand at a faster clip. Every new vertical brings new growth acceleration. What’s key here is plotting which verticals to move into, in what order and with which plan to automate and scale.”

- Product Inventory Per Vertical. “Product inventory within a vertical asks: how can Amazon go from selling 10 books to 10 million books to every book on the planet? Amazon’s growth is proportional to the depth of its product inventory per product vertical.”

- Traffic Per Product Page. “Product inventory is directly linked to product pages that are capable of yielding additional traffic all over the web. The lever here is converting traffic at a higher rate to buyers.”

- Conversion to Purchase and Average Purchase Value. “These components — the number of purchases and amount of each transaction by a customer — are strongly linked. Amazon optimizes this variable by injecting recommendation engines into the product. The company suggests a related product, which helps it convert another purchase and generate additional revenue.”

- Repeat Purchase Behavior. “Then eventually the business gets so sophisticated that they can build mechanisms to drive repeat purchase behavior, such as introducing products like Amazon Prime. You just buy and buy.”

That’s just one example of a growth model for a real business. “So, when you’re interviewing growth executives and they say, ‘Hey, I love your business and product’ ask them to run through this exercise first,” says Johns. “If they can’t do it, they’re full of it or not very good at their job. In both cases, they’re not fit to command the engine of your company.”

Can They Develop Rigorous Experimentation Programs?

At the end of the day, growth models and equations are theoretical; they need to be tested. So the next skill that a Head of Growth needs is the ability to develop rigorous experimentation programs. “This is more the classic definition of growth, which is to run a bunch of A/B tests. It goes a hell of a lot deeper,” says Johns. “I can’t emphasize enough how critical it is to evaluate the depth of their knowledge and skillset around experimentation. Some starter questions include: How do you identify what part of the funnel to focus on? How do you identify the most valuable test to run out of a set of experiments? When do you run — and not run — that test?”

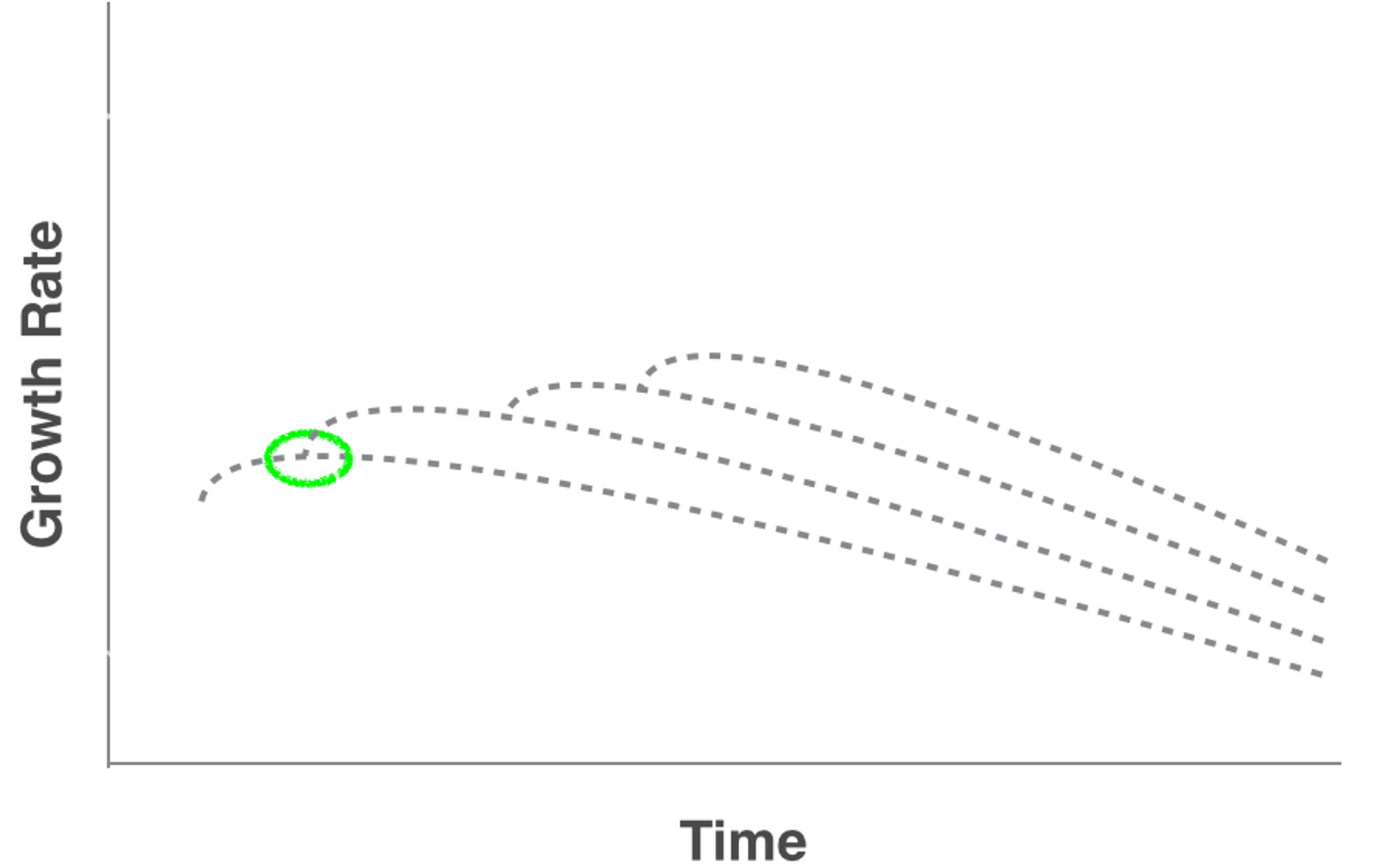

As you interview, push candidates to surface nuanced insights. Regarding experimentation, one of the behaviors that Johns has observed is that large companies really like small optimizations. “Bigger companies typically have a larger user base from which to test. Here’s a common approach that we took at Facebook: say there’s a part of the product that generates 100 million visitors per week. We could run an A/B test to 1% of that traffic and inside 24 hours have 100% confidence on the outcome of that experiment,” says Johns. “If it gave us a 5% change in user behavior, that’s wonderful. That would prompt us to do as many of those tests as fast as possible and let those bumps in growth compound.”

Back in 2008, that’s exactly what Facebook did. “That year, we finished the year with around 130 million monthly active users. Then, the board and executive team announced the goal for 2009: 300 million users,” says Johns. “It was daunting because it had taken many years just to get to 100 million. Now they wanted us to more than double in a year. At the time, we were growing roughly 1.5% week over week. If we grew at 2% week over week, we could hit the goal. That’s how we broke down the challenge and optimized experiments.”

If you’re not a social network with over a billion monthly active users, here’s a more relevant example if you are seeking to accelerate the growth of your user base:

Let’s say you’re a mid-sized company with 10 million users and you’re growing at 1% week over week. “So at the end of the first week you have 10.1 million users, and at year’s end, you serve 16.8 million users. Those are pretty good numbers — I’d probably write a check to that,” says Johns. “But let’s say the same company grows at 2% week over week. They start with 10 million monthly active users and end the year with 28 million. That’s even better.”

What most startups fail to consider is the third scenario. “The last column projects that you start at 1% week over week growth, but then let’s assume that the growth team is working on its active user rate,” says Johns. “So, every fourth week, the team improves that growth rate by 5% and it does that consistently over the next 52 weeks. Then you end up at 30.5 million users, which is more than the second scenario.”

That’s why big companies like small optimizations. “This is the philosophy behind Google engineers testing 40 different shades of blue in a particular sign up button,” he says. “When you’re a smaller company, that approach just doesn’t work because you don’t have 100 million users to throw in front of a ‘1% test.’ You have to do something different.”

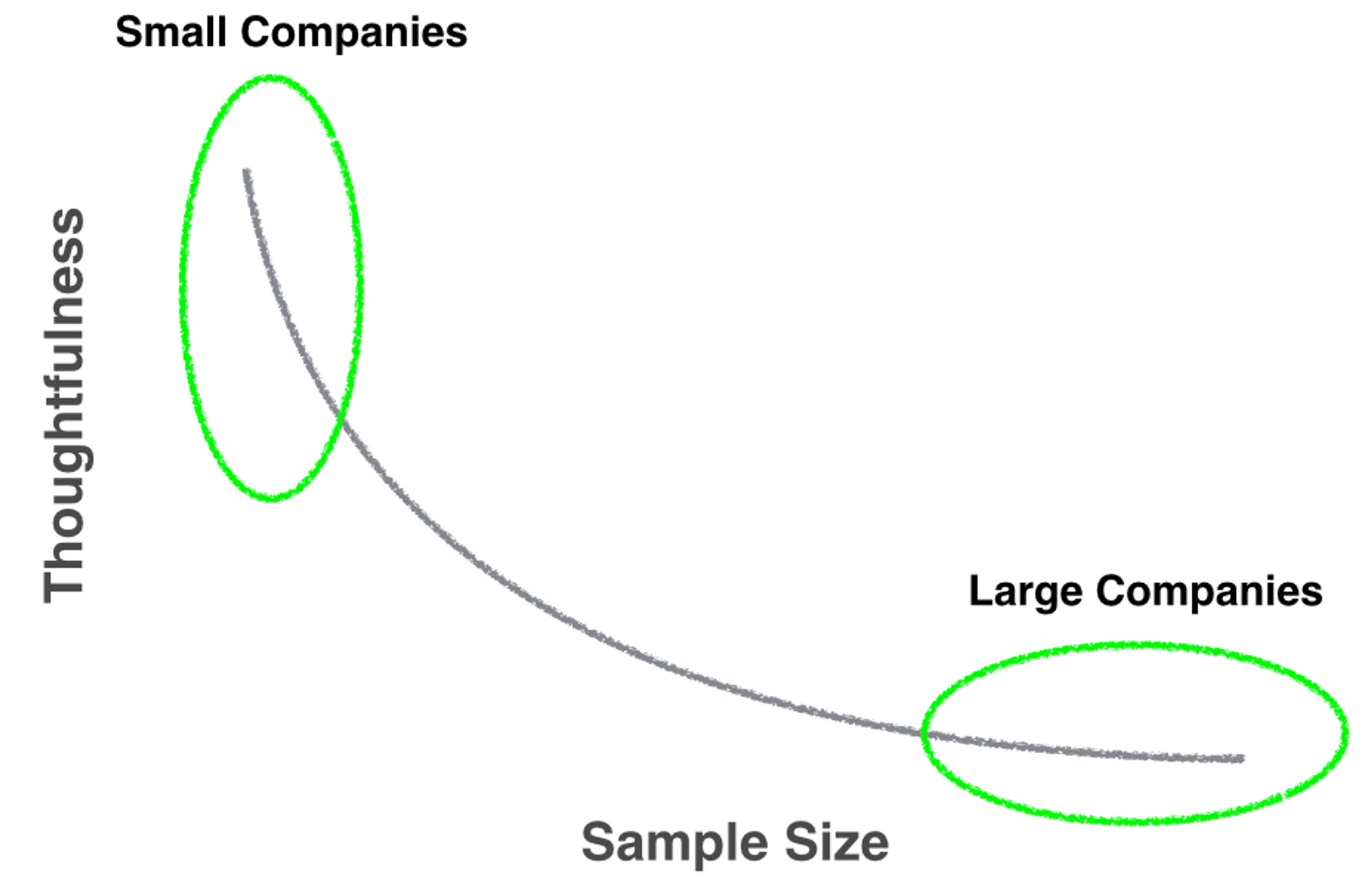

“This is probably my favorite graph, which is not scientific but very symbolic. On one axis you have thoughtfulness. It measures how thoughtful you are with the experiments that you’re designing, selecting and implementing. On on the X axis you have the sample of users you can draw from,” says Johns. “It turns out then when you have tons of traffic, people tend to not be that thoughtful. Larger companies field many half-baked ideas, but startups have to be more deliberate, precise and careful with their experiments.”

Can They Test In Different Parts of the Funnel?

Given that early to mid-stage companies have to be more thoughtful with their experimentation programs, they need to be disciplined with how they test within the funnel. “Startups only have so many opportunities to run an experiment in the product, and they’re also time bound by the cash they have in the bank,” says Johns. “With that said you need to run experiments that matter. Experiments that count when you are using smaller samples have to be incredibly thoughtful. Your future Head of Growth should understand that intuitively.”

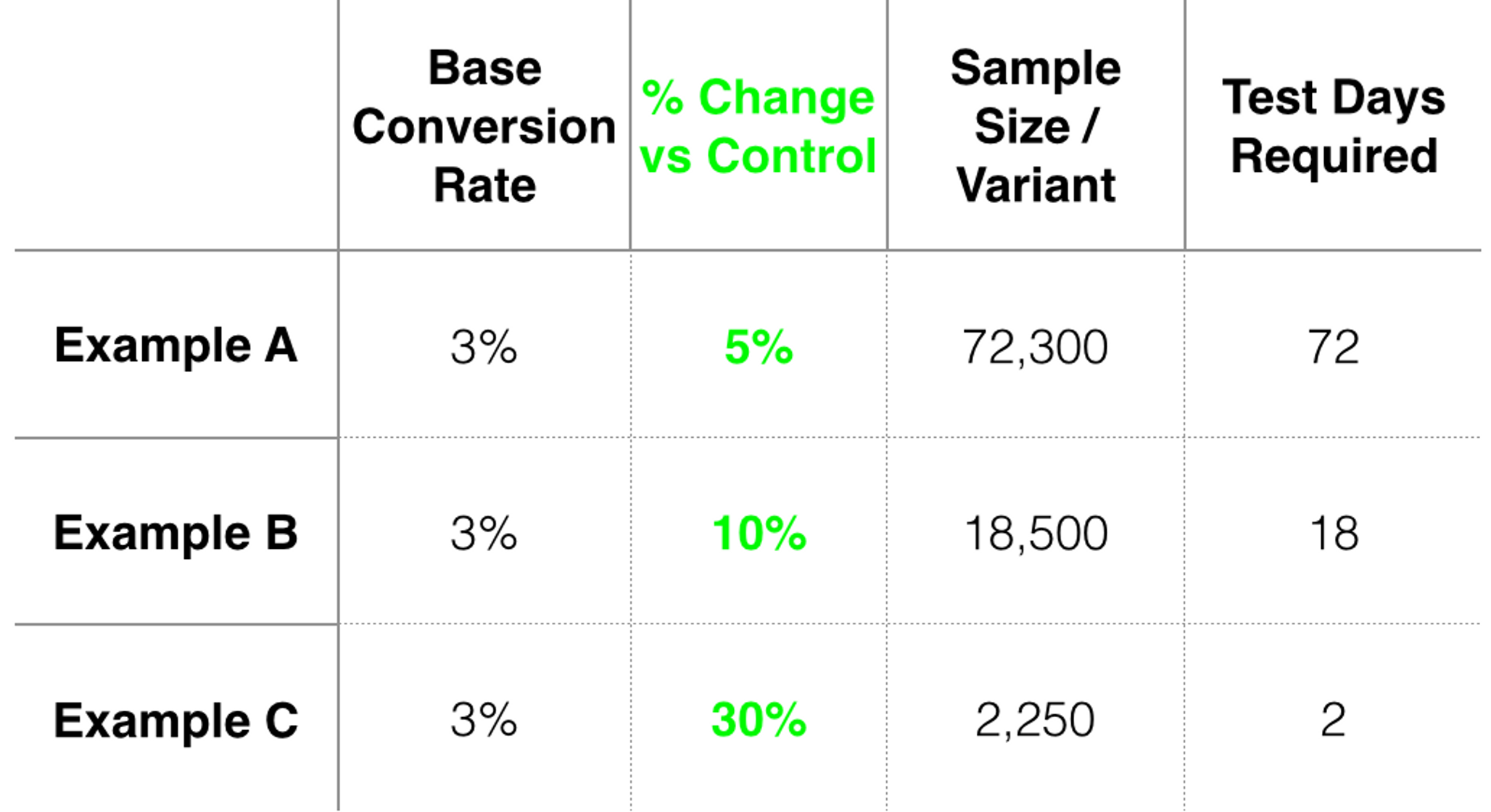

To root this point in tactics, Johns juxtaposes two analyses on experiment scenarios — one that examines the impact of a large lift over a control and the second that looks at the impact of different base conversion rates. Let’s look at the first scenario:

This chart looks at 3 A/B tests. The base conversion rate just refers to the ultimate conversion rate of users executing an act you want them to do. In this case, the focus is on the column in green, which captures the percent change over the control. So, for example, in Example A, a growth experiment was run and performed 5% better than the control that you’re testing against. Example C is 30% better.

Now look at the impact on the required sample size that will be needed to prove that the experiment is statistically better. For Example A, you will need more than 72,000 samples in both the experiment bucket and in the control bucket to execute the test. And importantly, you’ll need 72 days to detect if the experimented change is 5% better than the control. “That’s a lifetime when you’re a startup!” says Johns. “If you have 24 months of runway and you just spent nearly 3 months of it on an A/B test, that won’t foot the bill.”

Conversely, if you take Example C, it takes 2 days to measure if your experiment is 30% better. “Everyone wants those results. If you’re a startup, be thoughtful but also be dramatic in the changes that you’re willing to make,” says Johns. “Seriously. Be dramatic. Don’t just move a button on a page. You may run that experiment, given that you have small traffic sizes, and because of the small lift, you may run that test for months or years. Produce dramatic lifts if you’re a young startup.”

Testing rounded corners or 40 hues of blue won’t get the job done if you have small traffic sizes. Muster the courage to run experiments that can produce dramatic lift.

And if the experiment fails? “If it’s dramatically worse, you’ll find out in two days as well and that’s okay. Cut your losses and move on,” says Johns. “If it’s dramatically better, you earn that reward right now and let it compound as fast as you can.”

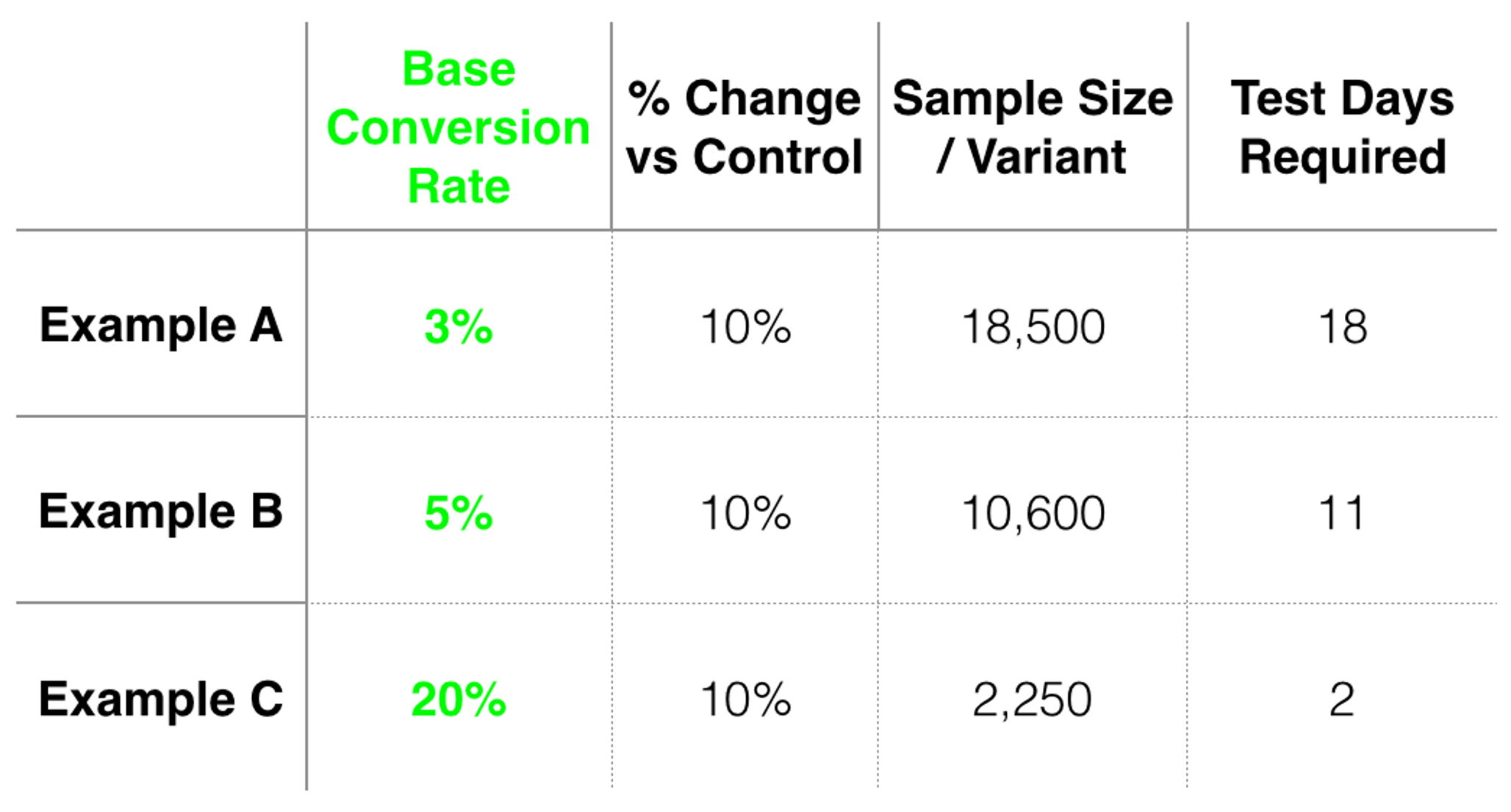

Now let’s make the base conversion rate the variable and evaluate the impact on sample size and the duration of the experiment. As a reminder, the base conversion rate refers to the ultimate conversion rate. “Let’s say you have 100 people on your homepage and you’re going to run an A/B test on it, from top to bottom,” says Johns. “If 100 people started on the homepage and 3 of them converted, that’s a 3% conversion rate. Or if, somewhere midway through the funnel, there are only 10 people on the page, but 3 convert, that’s a 30% base conversion rate.”

Taken another way, the base conversion is a proxy for the depth of the funnel. “The higher the base conversion rate generally the better,” he says. “So, for the same reason, you’ll notice that a 10% lift on a high base conversion rate — such as 20% as in Example C — allows me to detect an outcome in two days. On the other hand, if I have a small base conversion rate — such as in Example A —- that lifts by 10%, it will take nearly three weeks to evaluate the result.”

The takeaway here is to go deep in funnels. “That advice is especially true if you have a product that requires a significant purchase decision. If I'm going to buy something worth $1,000 online and if you want to drive the conversion rate on people actually buying it, don’t run a test on the homepage,” says Johns. “Run a test as part of the purchase funnel, where they enter their credit card details. That’s where you want to be testing, because you can resolve those tests more quickly given that you’re dealing with a committed customer. That type of customer is more likely to respond to a different design or experience. That’s where you want to test.”

Make sure your future head of growth can articulate and manipulate these charts, all the while clearly explaining how she picks her spot in the funnel. “Usually candidates say, ‘I'm going to test everything because I can run through it all quickly.’ Let me translate that for you: ‘I'm just going to throw spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks,’” he says. “That’s not your executive leader. Maybe that’s a good entry level person. But what you really want in a growth leader is someone who understands the value and benefit of intelligent experiment selection and design.”

Don’t hire a head of growth unless you have healthy organic growth first.

A Grabbag of Guidance on Growth

As you hire for your head of growth, Johns has a few stray suggestions:

You can’t sustainably grow something that sucks.“If you don’t have healthy organic growth, you have a product challenge. Hiring a growth leader isn’t the solution. Build your growth team after you demonstrate organic growth and a receptive market,” says Johns. “Frankly, you can’t sustainably grow something that sucks. Nothing replaces an incredible product.”

You don’t need or want a growth hacker to lead. “I say this from a recruiting perspective because it can be more of a bad sign. How many growth hackers do you know who have successfully executed on two to four years worth of growth work at Facebook, Pinterest, LinkedIn or Airbnb?” says Johns. “I don’t know any, but I know a lot of growth hackers that are clever and sophisticated in their own way. They understand tactics expertly and have worked on smaller products, but that’s it. You wouldn’t hire a finance hacker as your CFO, would you? Or a sales hacker as your Head of Sales at a SaaS company, right? Don’t fall sucker to that temptation.”

Your growth lead needs to be a product person. “A growth leader isn’t just a scientist experimenting,” says Johns. “With Wealthfront, the most meaningful changes that we make to the product are actually derivatives of deeper behavioral finance understandings. I like my chances with the candidate who comes in on Monday, having read a 30-page white paper based on two years’ worth of market research on how to get individuals to contribute to 401(k)s more often. That’s the person that finds the behavioral finance difference that we can integrate into the product that moves the needle.”

The most meaningful product changes will come from a deep intuition and empathy for the user of your product.

In order to establish an effective growth team and put an exception leader at its helm, a company must first demonstrate healthy organic growth. When it’s time to assemble a growth team, it’s critical that its leader can articulate the role of growth in the organization as well as have command over growth models, experimentation programs and various tests in the funnel. You’re looking for product-oriented, user-empathizing growth leader — not growth hacker.

“When it comes to growth at companies, there’s a spectrum of science and art. The artsy ones just build great products and don’t look at data or test. The scientific ones measure and test everything,” says Johns. “Your head of growth must be the fulcrum between those ends of the spectrum, balancing empathy and experimentation, passion and precision. It’s not an easy find, but when you do encounter one, do what you can to bring them on board.”