It was the middle of 2020, and it became clear to Slack’s Chief Product Officer Noah Desai Weiss that the product’s first-day user experience needed a complete overhaul.

Up until this point, the product team had tinkered with hundreds of little experiments to the core platform’s UI — all trying to inch towards optimizing the onboarding funnel for new teams signing up. But amidst all of the experimenting, Slack’s growth had plateaued.

“It was sort of like climbing a mountain range,” Weiss says. “We had reached the top of a small hill, but we knew that there were other bigger hills just out of sight. So we took a giant step back, and looked around to see what the rest of the terrain was.”

Staring down an onboarding funnel that wasn’t ramping as many new users up as they’d hoped, Weiss made the pivotal decision to do an entire overhaul of the first-day user experience. “We called it Project Day One. Everything from the moment a user landed on the website or the mobile app, through creating an account, onboarding the first few teammates, and starting an initial conversation was ripped up from the ground and scrapped.”

It was a huge swing — one that could have landed with a decisive thud. But it did exactly what Weiss had hoped, a new burst of energy to beat stagnant growth. “It took us to the top of a new hill and brought us higher up than ever before. It allowed us to see that there was still a lot more that we can climb.”

And it’s the type of gutsy call that has made Weiss one of the foremost product experts. Throughout his seven-year tenure at Slack, he’s run several parts of the product business — leading everything from new product features like Huddles and Clips to running the self-service SMB business. Before Slack, he led the product team at Foursquare, scaling the pre-revenue company from 3 million users to over 50 million, bringing in $35 million in revenue.

In this exclusive interview, he opens up the decision-making playbook he’s relied on as a product leader at Google (leading the structured data team), Foursquare, and now at Slack. His goal? Help product folks take bigger, bolder bets with product decisions — ones that will bring in outsized returns, not just incremental shifts.

He starts by sharing his contrarian takes on two popular pieces of product strategy advice. Then, he walks us through the three-step process he uses to operationalize quality decision-making. (Spoiler alert: it boils down to sharing context, building trust and factoring in risk.) He wraps by zooming out and sharing how Slack’s product team thinks about making big bets, sharing two tactical ways to embed calculated risk into your product roadmap.

Judgment and intuition may seem like squishier skills that aren’t easily honed. But these decision-making principles apply to folks up and down the ladder, from an entry-level PM to a senior product leader. With Weiss’s tested frameworks to guide you, taking big swings will start to feel more routine and familiar, rather than daunting and insurmountable.

Hot Take #1: You can’t experiment your way out of every product problem

So much of decision-making comes down to what informs your choices — our outputs are only as strong as the inputs we are given. Weiss breaks down product inputs into two schools of thought: quantitative and qualitative. Ask any product leader which they favor, and chances are they lean towards letting the numbers talk. But Weiss feels taking the latter approach has some underrated merits.

“One of the things that we talk a lot about at Slack, which is very much in contrast to my early days at Google, is about not being data-driven with every decision that you make,” Weiss says. “Data can help solve easy problems, but it doesn’t actually solve the hard problems.”

A hard problem, he says, can’t be solved by experimenting your way out of it. “You have to figure out if it’s a big swing you want to take. You do that by using intuition.”

The distinction Weiss makes here is that the solutions to meaty, strategic problems product leaders face can be data-informed, but shouldn’t rely solely on data as a crutch.

It’s become fashionable to say that everything can be empirically answered by data. The ethos, especially in product, is unless you are doing everything as an experiment, then you are doing it wrong. And I disagree with that.

So when it comes to mapping this back to his own product decision-making process, Weiss likes to start any project by asking three questions:

- 1. What is the problem we are trying to solve for customers?

- 2. Why do we think this approach would help them?

- 3. What impact do we expect this to have? Whether measurable or immeasurable.

When you reach the third and final question, that is when to decide whether you can run some tests and experiments or if you have to learn about it through other means, he says.

“An unhealthy approach that you sometimes see with growth teams is this addiction to the velocity of experimentation,” he says. “Growth teams stop thinking about ‘the why’ behind what you’re doing and start focusing more on experimenting without thought. The hope is that you end up in a better place than where you started.”

That’s not to say there is no room for experimentation on a product team — quite the opposite. But Weiss argues that a strategic product leader knows the difference between when to experiment on something, rather than running tests willy-nilly.

“Certain types of product features are more conducive to experimentation, like when you are making isolated changes. A good example of this is A/B testing a checkout page, where you are trying to consolidate time to checkout from four steps to two steps. That's a great place where you can empirically answer does this change increase the conversion rate?”

But for many other types of change, and definitely for most early products, product leaders don't even have the scale or the time to run a test that gets statistical significance. “In those cases, you have to use intuition, judgment and strategy a lot more,” says Weiss

For larger, bolder features (like Slack’s new day-one interface) decisions should be taste-driven. “For decisions that hinge on what our customers love, we’ll always consult the data, but gut checks and strategy steer those bigger, bolder ship decisions.”

Hot Take #2: Focus on your own hand, not the whole card table

Let’s say you’ve sat down for a game of poker. What are you focusing on more — the hand you have in front of you, or the outcome of the whole table? If you picked the latter, you aren’t alone. Poker champion (and First Round’s Special Partner in Decision Science) Annie Duke dedicates a whole section in her bestselling book “Thinking in Bets” to this line of thinking. It’s called resulting — and it can be costly.

Weiss counts himself as a fan of Duke’s frameworks, and this one in particular. “She explains that if you look at how a hand played out, as opposed to how you played the hand, you can take away lots of really bad lessons on how to play poker. Because even if you happen to take the whole pot, you might be missing that you just got really lucky when the final cards hit the table, and that doesn’t serve you well for next time.”

Resulting can also be applied to quality product decision-making. “You can still use the outcomes of your decisions over time in aggregate as a signal, but trying to evaluate yourself or a team based on a single outcome at a single point in time is likely going to draw a lot of spurious conclusions,” he says.

An alternative approach is to get comfortable making smaller changes in increments over time. “If we go back to our mountain metaphor, oftentimes product leaders are staring down their next summit with little to no visibility,” Weiss says. “Have trust that the incremental decisions you make over a longer period will provide more valuable learning lessons to inform each decision you make going forward.”

It’s easy to get swept up in a grand vision, but realistically you can’t deploy a feature and get five years’ worth of feedback and learnings in an instant. How will you know what will resonate with customers? How do you know what the market will react to?

How to operationalize for quality product decisions: The startup leader’s playbook

Product leaders have to make tough calls, often without any real data or historical precedents to rely on as guideposts. But there is a way product leaders can think about operationalizing their decision-making process, and a lot of wisdom can be borrowed from how product is run at early-stage startups, Weiss says.

“At these places where there are only ten, 20, or 30 people at the company, it’s hard to even know whether you are making quality decisions because you may not even have a product on the market,” he says. “But on the flip side, the reasons that make startups feel so risky also enable them to be excellent grounds for decision making.”

He breaks down the three bedrocks of quality decision-making, explaining how early-stage startups get this right and how to keep up the pace as your product team scales.

1. Share context

“Almost always, when I look at a team or project at a larger org trying to make a decision with differences in opinions, the root of those differences almost always starts with shared context,” Weiss says. “Or lack thereof.”

The first step to identifying if your team is lacking shared context is to ask yourself a series of questions, Weiss says. “Does everyone making the decision have the same knowledge and information? Is everyone using the same backdrop to weigh the pros and cons fairly?”

In Weiss’s experience, the answer is more often than not a resounding no. “Alignment is the fundamental challenge with almost every large company,” he says. “Communication is hard, and people are just busy. But if you can crack the code and keep your organization aligned and focused, it’s like a superpower for velocity.”

- What startups get right here: “There is a tremendous amount of shared context that a smaller group has in every direction about the mission, the strategy, the customer, or what they are trying to achieve,” Weiss says. “That context becomes a shared language used when they are trying to make decisions.”

Be transparent, and then hit repeat.

The two fundamental practices to start cracking this code are transparency and repetition, according to Weiss.

On the transparency front, making information widely available for every person weighing in on a decision is crucial to making sure product teams are inputting a chorus of different voices and avoiding blind spots.

“Leaders can do this by simply sharing everything they possibly can with their teammates and those directly involved with the decision at hand,” says Weiss. “But the real kicker here is repetition. Keep grounding back in the context that matters most for the decision you are making, because people tend to need reminders,” he says.

Assume that if you don’t talk about something after a month, people will have forgotten about it by then. Alignment isn’t static. You don’t get to do it just once.

2. Build trust

Maintaining and preserving shared context is only one piece of the puzzle. Product leaders often find themselves charged with gathering consensus from teams across the organization — often with a level of healthy pushback. “In order to do this well, you have to have a decisive point of view, yourself,” Weiss says.

- What startups get right here: “At early-stage companies, there’s usually a high degree of trust. And with that trust, folks wind up pushing each other’s thinking more. There’s an expectation that you can push on ideas and not come across as threatening.”

If there’s no trust, it’s really hard for there to be conflict. And healthy conflict is necessary to get to any great resolution.

When a decision goes well, no doubt there is glory to whoever’s name is attached to an idea. But it’s that sliver of ownership that Weiss says rattles so many talented startup leaders into even attaching their name to something in the first place.

“Nobody wants to be attributed to a bad decision,” Weiss says. “No one wants to stick their neck out there, even if they were going off the inputs they had at the time. If it suddenly turns out to be a disaster, no one wants to be at fault. People become paralyzed with fear, and then you have a consensus-driven approach because no one wants to take ownership.”

Relying too much on consensus-driven decisions is the biggest mistake Weiss sees in product teams at scaling companies.

When you are guided by consensus, it often means you are reaching the most vanilla or neutral outcomes.

To inject some startup-level trust into your org at a larger team, Weiss says the best way to do this is to practice consistency. “Repetition is the best strategy you can use to build trust,” Weiss says. “My old board members at a previous company used to say, ‘The best leaders say what they are going to do, do what they said or let you know why doing it wasn’t possible.’ You’ll know you’ve built that trust when your team feels their expectations are met after you announce a decision.”

It doesn’t especially matter what product leaders are sharing with their teams, but Weiss says it matters more that reports know the information they are receiving is transparent .“By exercising this transparency over and over again, it’s possible to build trust with folks across your organization in a scalable way.”

Another transparency technique Weiss recommends for product leaders is to borrow from their engineering counterparts and set up a blameless post-mortem at your next team meeting. The main idea here is to shift the blame from an individual when an outcome goes haywire to being an organizational failure instead.

You want to avoid a culture where people become petrified of having high convictions and feeling the blame when the results of their ideas don’t work out as planned.

Building this type of culture must be intentional, according to Weiss. “This doesn’t stop just at post-mortem meetings. You need to have a culture where you’re not putting individual blame when outcomes go wrong. On any individual decision, optimize for the pace of learning and the impact will follow.”

3. Factor in risk

As a product leader at a growing company, the decisions you make only become more high-stakes. Each potential product or feature change impacts a wider customer base, more voices chime in with warnings of what could go wrong, and the risk of failure looms larger.

It's only natural then, for potential negative consequences to give you pause. After all, a misstep could carry painful repercussions — for customers and users, for your team's momentum, and for your own career trajectory. This inclination towards risk aversion is understandable, says Weiss.

However, playing it safe also carries a cost. Opportunities are missed, innovation gets left on the table, and — possibly the biggest blow to scaling companies — progress can gradually grind to a halt. The key, Weiss says, is finding the right balance, fully evaluating risks while not becoming paralyzed into inaction, and operating with enough confidence to move forward decisively.

- What startups get right here: Early-stage startups are inherently risky — and taking big swings comes with the territory. After all, there aren’t too many wholly safe bets when you’re building from 0-1. On high-performing startup teams, this risk is acknowledged, rather than an emergency break to pull that grinds projects to a halt.

One-way vs. two-way door decisions

A key skill for any seasoned product leader is knowing which choices warrant careful scrutiny and which don't require sweating the small stuff. Not all decisions carry equal weight.

One useful framework Weiss offers for thinking through decisions is Amazon’s “one-way” vs “two-way door” model. By splitting potential choices into "one-way doors" and "two-way doors,” Amazon founder Jeff Bezos was able to dial up his decision-making pace to an electric speed. Weiss is a big fan of this framework and even had his team adopt the philosophy. Here’s how he breaks it down:

- Two-way doors: “For example, it can feel very fraught when deciding on a new tagline for the homepage. It’s very prominent and visible. Thus, you can spend months internally debating and focus group testing, and still end up with an option that no one person wants to 100% claim. But, while visible, a new homepage tagline is an incredibly easy decision to reverse. This is an example of a two-way door. Teams should feel comfortable walking through this decision knowing that making any changes or updates to the tagline will be easy to revert.”

- One-way doors: These are decisions that are much harder to reverse. “These have long-term repercussions and are hard to de-risk,” says Weiss. For example, changing the name of a core product. Once product leaders identify an upcoming decision as a one-way door, Weiss encourages giving yourself enough time to work through what the biggest risks are ahead of time, so you can be more judicious.

We have this saying at Slack that you should walk confidently through two-way door decisions. Which is to say, don’t be paralyzed by things that are easily reversible.

The more two-way door decisions product leaders can identify, the faster they can move. But Weiss adds one last thing to consider when making speed a habit. “You want to make sure that all your teams know that most of the decisions you are going to make are two-way doors, and set the expectation that these will be made with a faster pace,” Weiss says. “By making a distinction between the types of decisions that come across your desk, this will afford you trust from your team when you do need to move slowly on a one-way door decision.”

Diversify your risk with the 70:20:10 product roadmap rule

Now with frameworks in place to make speedy decisions with conviction, Weiss encourages product leaders to also consider the potential each decision has to change their business. He singles out another common problem of scaling orgs that are likely inhibiting bigger bet-taking.

“The inclination that’s developed over time for product orgs is to have a localized team that’s focused on a subset of the feature space, and you have one or two KPIs to meet,” he says. “And in any given quarter, success for the product leader and the team is incrementally moving that KPI you are directly responsible for.”

When Slack’s product leaders sit down to review their team’s roadmaps, diversification is key. “We look at the portfolio and make sure no two teams have the same exact mix of the type of goals they are working on,” he says.

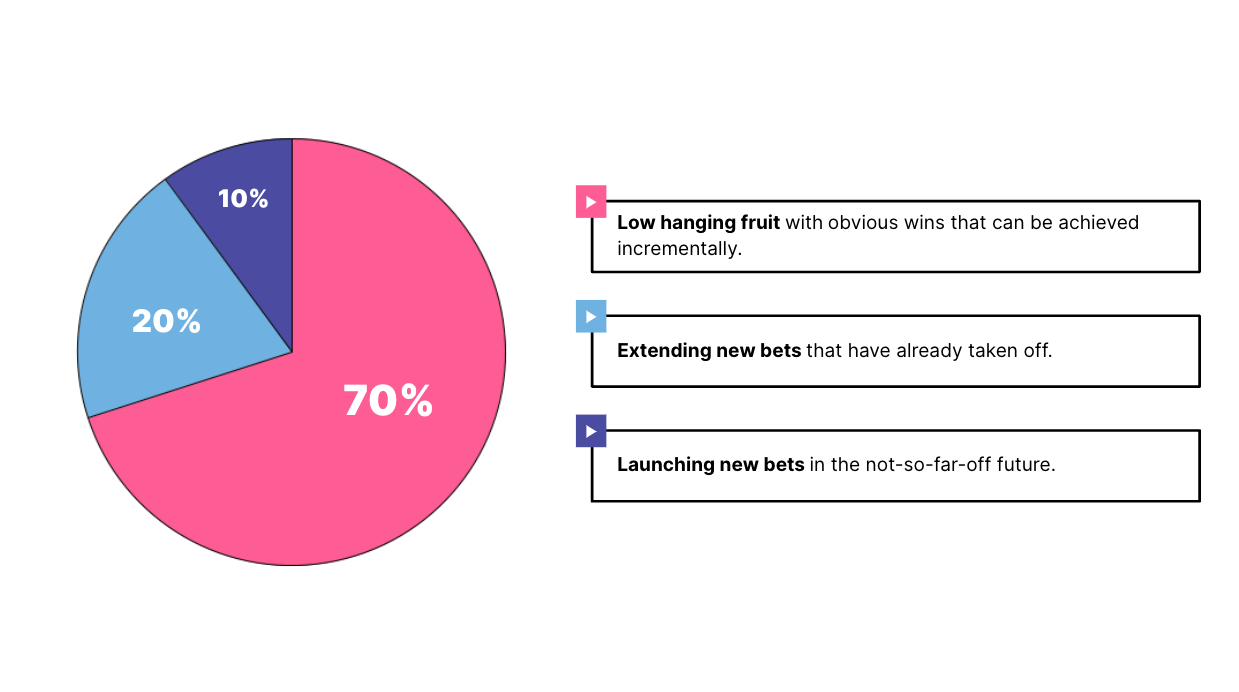

Reviewing product roadmaps from this lens also allows the product team to examine if goals along the roadmap are taking big enough swings. Here, Weiss leans on the 70:20:10 model that he picked up from his time at Google.

They are tentpole products now, but there was a time when Gmail and Google Maps fell into that 20% category, Weiss says. “The logic was to keep investing in those bets even though they weren’t fully at scale yet. And the 10% category was around self-driving cars and AI.”

Even if you don’t yet have a multi-product suite, these same principles of balancing big bets with low-hanging fruit can still be applied. “Just be deliberate about what your allocation looks like and how it’s changing over time,” Weiss says.

Wrapping Up: Don’t write off the power of well-defined values

The process, depth and quality of a decision can be measured and mulled over ad nauseam, but ultimately, without an organizational culture that promotes autonomy and risk-taking, all of these frameworks become moot, according to Weiss.

“Slack actually created a product principle called take bigger, bolder bets. Which sounds like an obvious guiding statement for a product team, but the reality of working as one person inside a 1000+ person product development team is there are a lot of laws of gravity as an organization that prohibits you from doing so,” says Weiss.

Outside of the product team, Weiss points to Slack’s company-wide value of humility as a big motivator in the choices he makes every day. “When we unpack what humility means, it means being introspective. Being comfortable being self-critical. Not just as an individual but as an organization. Our company has always been pretty good at being self-critical and not assuming the momentum from the past year is guaranteed to continue forever in the future,” Weiss says. “Without being self-flagellating, we can still be self-critical. And I believe that having this awareness is where our biggest turning points came from.”

This article is a lightly edited summary of our podcast episode with Weiss. You can listen to the full episode here.