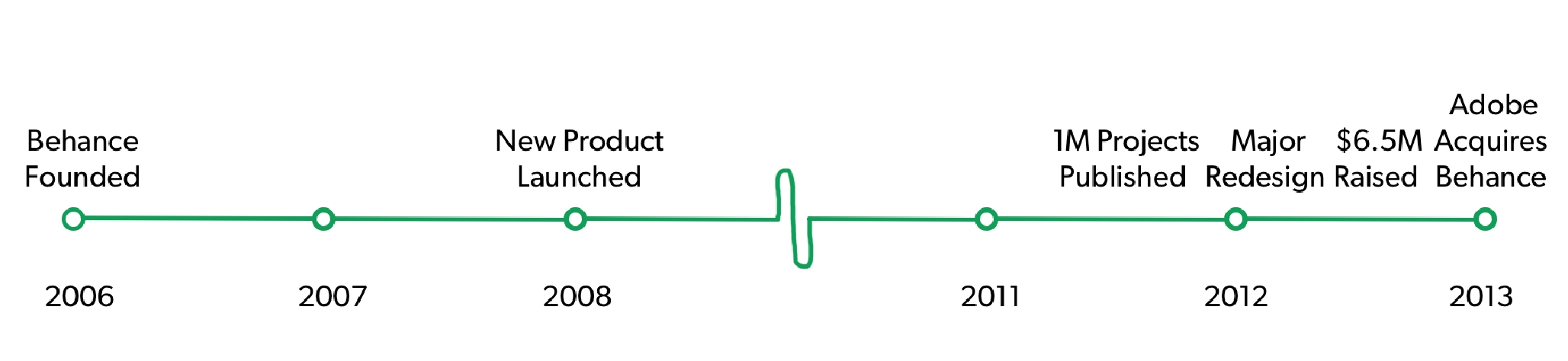

A quick search of social portfolio platform Behance on Techcrunch returns the expected results (its fundraise and acquisition) as well as a few milestones (a new product, a major redesign and its one millionth published project). But plot this coverage on a timeline and a trend emerges: Behance’s middle years are largely left out of the headlines — and coverage clusters at its launch and exit.

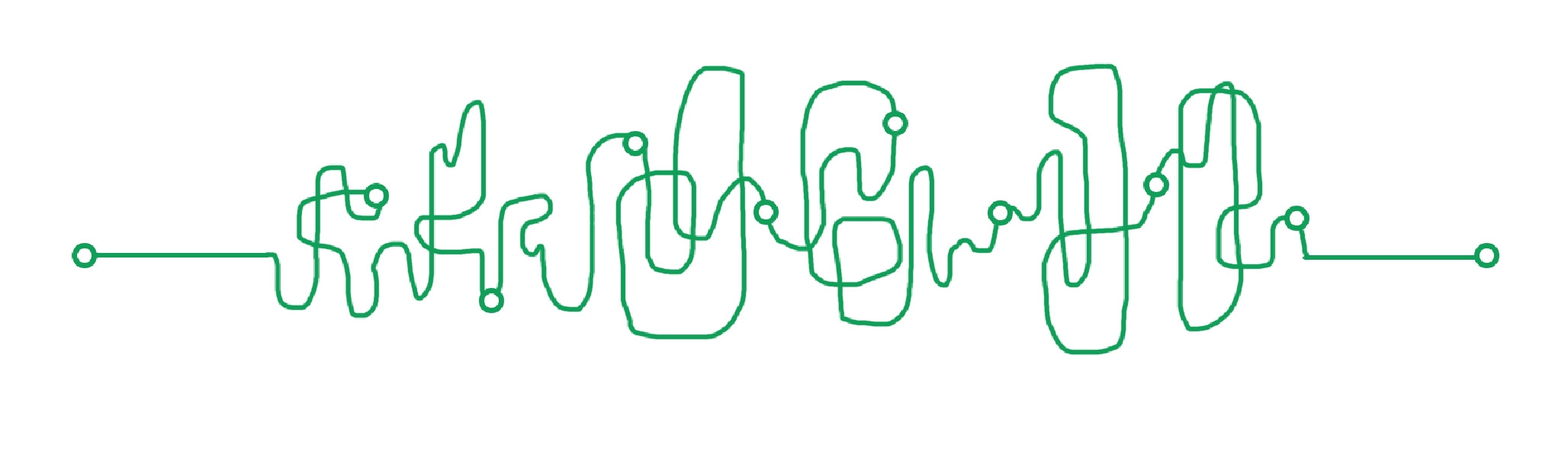

Talk to Behance founder Scott Belsky and the story’s different. The middle years were the most complicated, and also the most innovative. For the company, they were the most noteworthy — even if not the most newsworthy — in positioning Behance for growth and scale. And the company’s timeline didn’t feel like an even unfurling of events. In fact, to Belsky, this is a much more accurate representation of the evolution of Behance — and any technology company for that matter:

Beyond founding Behance, Belsky has lived and studied technology startups from a number of vantage points — as advisor (Uber, Pinterest, sweetgreen), author (Making Ideas Happen), investor (Benchmark), and Adobe’s Chief Product Officer — and observes that the most critical part of a startup’s journey is the least discussed and most misunderstood: the middle. We tend to glorify the first and final mile of an endeavor, to the detriment the road between the endpoints: the part that makes or breaks a venture.

Today, Belsky releases his new book, The Messy Middle, in which he digs into the volatile stretch between start and finish, bringing lessons on how founders and leaders can endure and optimize their team, product and themselves to survive — and excel. He covers an expansive range of topics, from constructing teams (“If you avoid folks who are polarizing, you avoid bold outcomes”) to culture and tools (“Be frugal with everything except your bed, your chair, your space, and your team”) to anchoring to your customers (“empathy and humility before passion”).

With The Messy Middle hot off the press, we’re pleased to present Belsky’s introduction to his “Optimizing Product” chapter, as well as three tactic-laden sections on simplifying and iterating products. Read on for new thinking and enduring advice from Belsky, one of the most insightful minds you’ll find on building products, teams and companies.

OPTIMIZING PRODUCT

A quick note before we begin. This next section is all about optimizing your product. The journey of building and endlessly iterating a product or service is a field unto itself, flush with best practices in design, product management, customer research, and psychology. I have approached this section as a book within the book, recognizing that some readers deep in the process of building products may skip to it while others skip it altogether. Regardless of the nature of your work, these principles demonstrate how remarkable products are made in the middle. All right, let’s talk product.

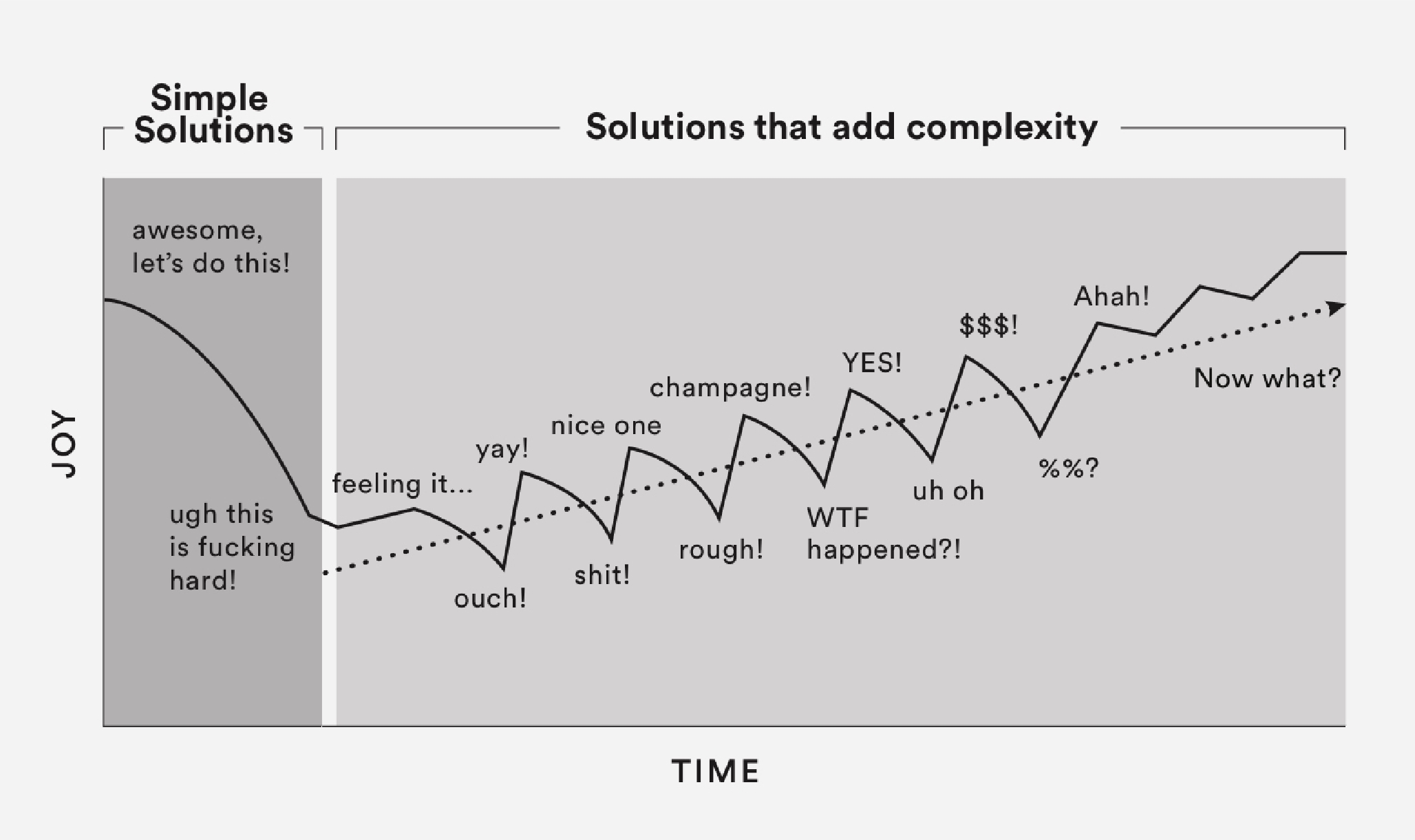

The honeymoon phase at the start of a venture is known not only for its boundless energy but also its remarkable clarity. In the beginning of your journey, simple solutions come easily. But as the middle becomes volatile and more problematic, we have the tendency to add complexity. We solve problems by adding more options, more features, and more nuances to our creations.

While a new product’s simplicity is a competitive advantage, it evolves and becomes more complex over time. The unfortunate result is what I have come to call “the product life cycle” and it applies to any type of service or experience you’re creating, your “product.”

The Product Life Cycle

- 1. Customers flock to a simple product.

- 2. The product adds new features to better serve customers and grow the business.

- 3. Product gets complicated.

- 4. Customers flock to another simple product.

Simple is sticky. It is very hard to make a product—or any customer experience—simple. It is even harder to keep it simple. The more obvious and intuitive a product is, the harder it is to optimize it without adding complication.

Successfully optimizing your product, whatever it may be, means making it both more powerful and more accessible. The key to striking this balance is grounding the decisions you make with simple convictions, the absolute simplest being, Life is just time and how you use it.

Every product or service in your life either helps you spend time or save time. The news channels or shows you watch, the social apps like Facebook and Snapchat that you use, the books you read, and the games you play all compete for how you spend your time. Other products, like Uber (getting a car faster), Slack (communicating with your team faster), and Amazon’s Alexa (buying things faster) exist to help you save time. And it’s not just digital ventures: businesses like bakeries and restaurants that sell prepared foods fall into this category as well. The only exceptions are rare products like Twitter (a quicker way to consume more information) or Blue Apron (a quicker way to cook at home) that add a time-consuming action to your plate while also making that experience faster than it normally would be.

The fact of the matter is that we are constantly battling time, whether to save or spend it. We’re fiercely aware and protective of our time. The only time we’re not focused on time is when our natural human tendencies—like wanting to look good, satisfy curiosity, or be recognized by others—make us lose track of it.

Natural human tendencies are the twilight zone for time. When you account for these tendencies when developing your product, you win your customer’s time.

As I reflect on the new products that have improved my life the most over the years, they ultimately removed a daily friction. Apps on my phone like Google Maps brought the city to my fingertips and helped ensure I’d never get lost again. Products like Uber eliminated the burden of arranging transportation or finding a cab. Decades earlier, companies like FedEx and UPS enabled people to ship something anywhere in the world by filling out a simple form rather than dealing with multiple carriers. Throughout history, many of the best businesses have hunted friction and eliminated it to save people time.

Optimizing the product you’re making is ultimately about making it more human-friendly and accommodating to natural human tendencies. The insights ahead are intended to fine-tune your product logic. How do you improve the first mile of your customer’s experience of your product? How do you maintain simplicity in the face of new challenges and accommodating new types of customers? How do you make your product increasingly relevant and engaging? How do you keep optimizing your product and marketing to better serve your customers’ needs?

Optimizing product experiences is a field of study in itself. While the next two sections on optimizing products have a bias toward digital products, I believe that these insights apply to all kinds of products, services, and experiences.

Take great pride in your product, but not at the expense of failing to see its problems. As soon as your product stops evolving, you lose. As soon as you are satisfied, you become complacent. Never be truly satisfied: When you’re creating, the current version of your product should always feel underwhelming.

In many ways, the state of your product is a mirror of the state of your team.

All that we have talked about when it comes to enduring the middle miles and optimizing how your team performs comes to the surface when your customers experience what you’ve created. The pursuit of a great product requires discipline, endless iteration, and grounding your objectives with your customers’ struggles and psychology.

Never stop crafting the first mile of your product's experience.

Whether you’re building a product, creating art, or writing a book, you need to remember that your customers or patrons make sweeping judgments in their first experience interacting with your creation – especially in the first thirty seconds. I call this the “first mile,” and it is the most critical yet underserved part of a product.

You only get one chance to make a first impression. In a world of moving fast and pushing out a minimum viable product, the first mile of a user’s experience is almost always an afterthought. For physical products, that could be the packaging, the wording of the instructions, and the labels that help orientate a new customer. For digital products, it could be the onboarding process, the explanatory copy, and the default settings of your product. When we spend so much time focusing on making what’s behind a locked door so brilliant, we sometimes forget to give the user the key.

A failed first mile cripples a new product right out of the gate. You may get loads of downloads, pre-sales, or sign-ups, but very few customers will get past the onboarding process to start actually using your product. And even if they do, your customers need to feel successful quickly. You need to prime your audience to the point where they know three things:

- Why they’re there

- What they can accomplish

- What to do next

Consider, for example, a product like Adobe XD, one of Adobe’s newest and fastest growing platforms for experience designers (people who design interfaces of all kinds, websites, mobile apps, and anything else that graces a screen or helps people navigate an experience). As soon as you open the product for the first time, you should know why you’re there (to design that cool app you have an idea for), what you can accomplish (the vast array of experiences you can design for, as represented by examples and a list of ways to get started), and what to do next (it should always be clear what your next step is—and the sequence of steps you must take to be successful).

Once a new user knows these three things, they have reached a place in your product experience where they are willing to invest time and energy to build a relationship with your product. They don’t need to actually know how to use your entire product at the beginning—they just need to trust you and know what their immediate next step is.

Much of what I know about the first mile of product experience I learned the hard way while building Bēhance’s products and working with other startups. In the earliest version of Bēhance, we had so many steps and questions in the sign-up process. For example, we asked new members to select their top three creative fields, like photography, photojournalism, or illustration. There were a lot of options, and new users took an average of 120 seconds to browse the list and select their top fields. It was helpful for both of us to know who our users were and for the users to instantly connect to communities, but we lost over 10 percent of new members at this particular step in the sign-up process. We decided to remove it and resolved ourselves to capture this information later on, sometime after the first mile once new Bēhance users were actively using the product and willing to give us the benefit of the doubt. We reduced or altogether removed other steps as well. As a result, sign-ups went up by approximately 14 percent.

Reducing and iterating the first mile experience had a greater impact on growth than any other new feature that year.

Over the years since, I have worked with dozens of other companies trying to optimize the first mile of their customer experience—whether it was Pinterest’s first version of welcoming new users that aimed to maximize the number of “pin boards” each user was following, Uber’s way of describing itself to new users when it first launched, sweetgreen’s mobile application for ordering salads for pickup, Periscope’s live-streaming application, or mobile creative applications at Adobe — and every product suffers the same challenge: helping customers understand why they’re there, what they can accomplish, and what to do next in as few steps, words, and seconds as possible.

Established products are not immune to this problem. Consider Twitter, a product that engages millions of people but struggled to optimize the first mile. For a subset of users—perhaps the first 150 million or so—an onboarding experience that required new users to select accounts to follow was sufficient. However, at some point Twitter encountered a new cohort of customers that didn’t have the patience or desire to curate their own feed. They just wanted the news, and Twitter’s first mile experience was much more difficult than switching on the television or going to a website. Even though their core product improved, Twitter struggled to get new users to build a relationship with the product — and growth stalled as a result.

Especially for new companies, these crucial components of initial engagement are typically addressed in haste as a product is launching. The “top of the funnel” for engaging new people with your product is your ultimate source of growth, and yet such early aspects of the product experience like designing a “tour” for your product and determining what the default experience should be are all-too-often afterthoughts. In some teams, I have even seen these pieces outsourced or delegated to a single person to figure out on her own.

To make matters worse, the first mile of a product experience is increasingly neglected over time despite becoming more important over time. As your product reaches beyond early adopters, the first mile will need to be even simpler and account for vastly different groups of “newest users,” not just the power users you were originally hoping to attract. New customers are not the same over time; if they were, you would have snared them in the opening round. The first mile requires therefore continuous scrutiny after launch. Just because you’re accommodating fresh users well now doesn’t mean the same approach will work in the future as you attract wider and different audiences. Without constantly reconsidering your assumptions for what new users need, you’ll fail to accommodate the cohorts that will bring your product into the mainstream. As products scale across demographics, generations, and nationalities, your first mile will need to change.

The first mile of your customer’s experience using your product cannot be the last mile of your experience building the product.

For any product with aggressive growth aspirations, I’d argue that more than 30 percent of your energy should be allocated to the first mile of your product — even when you’re well into your journey. It’s the very top of your funnel for new users, and it therefore needs to be one of the most thought-out parts of your product, not an afterthought.

Optimize the first 30 seconds for laziness, vanity and selfishness.

Within that first mile, the first 30 seconds of the sprint determines if people will keep running the whole distance. During these first 30 seconds of every new experience, people are lazy, vain, and selfish. This is not intended as a cynical jab at humanity. It’s an essential insight for building great products and experiences both online and off-. It is a humbling realization that everyone you meet — and everyone that visits your website or uses your products — has an entirely different mind-set before they’re ready to make the effort to care.

We are lazy in the sense that we don’t want to invest time and energy to unwrap and understand what something is. We have no patience to read directions. No time to deviate. No will to learn. Life has such a steep learning curve as it is with seldom enough time for work, play, learning, and love. So, when something entirely new requires too much effort, we just let it pass. Our default is to avoid things that take work until we’re convinced of the benefits.

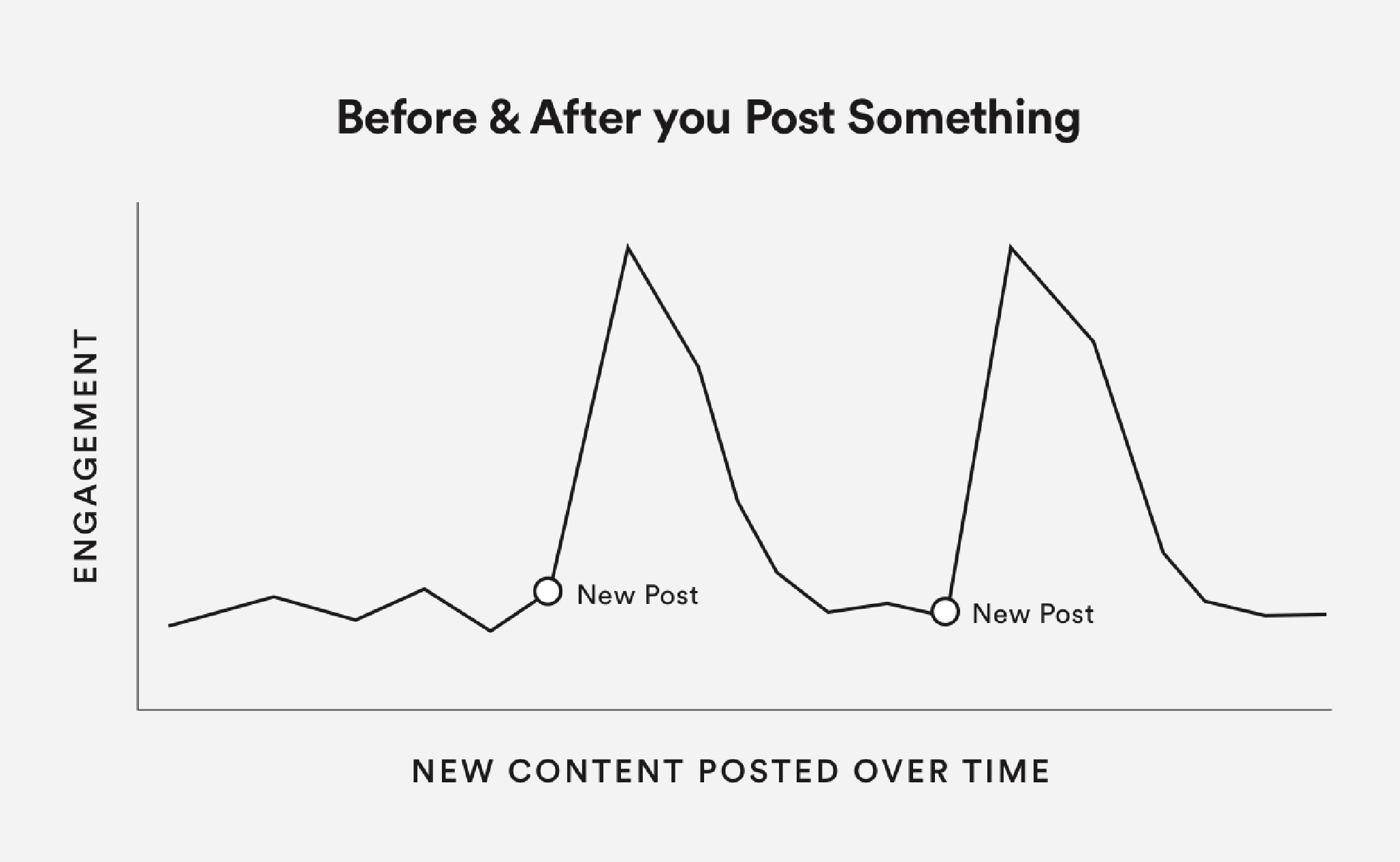

We are vain because we care how we come across to others, at least initially. Mirrors, hair product, and social media all provide a quick return of self-assurance for how we appear to others. For this reason, products like Instagram and Twitter are geared to yield you likes and friends as quickly as possible; no one wants to start using a new product if you have no one to share it with. While the majority of your time on a product like Instagram may be spent browsing your friends’ content, if you pay attention to your behavior using the product, you’ll notice the tendency to open the app more frequently immediately after posting a new image.

You want to see what people are saying about your content, and you’ll keep checking. Instagram’s activity feed is an example of what I’ve come to call “ego analytics”; it shows you what people are saying and strokes your ego after taking the risk to publish or share a creation of your own. The same goes for other apps, as well as gallery openings, press coverage, and book launches. We are all hardwired to tune in to what others are saying about us if given the opportunity to do so.

For product designers, ego analytics is a critical mechanism to keep users contributing and engaged. The fact that creative apps are more about seeing who saw your content than seeing others’ content is telling. Rather than open our aperture to browse and discover the world’s creations, we perseverate over the performance of our own. Our vanity routinely sucks the gravity out of any creative opportunity.

Of course, the more we know our friends and loved ones, the less we judge them and posture ourselves for them — but until they know you, you want to look good. These ego analytics are a very powerful form of engagement because vanity rules the first 30 seconds.

We are selfish because we must also care for ourselves. When you engage with a product or service, you want an immediate return that exceeds your initial investment. Instruction manuals, laborious unpacking, extensive sign-up processes, and other friction points that obstruct getting a quick return from engagement are alienating. New customers need something quick, right now, regardless of what they may get later.

This lazy-vain-selfish principle is true for all kinds of product experiences, online and offline.

In the first 15 seconds, your visitors are lazy in the sense that they have no extra time to invest in something they don’t know. They are vain in that they want to look good from the get-go when they engage with your product or service. And they’re selfish in that despite the big-picture potential and purpose of what your product stands for, they want to know how it will immediately benefit them.

As a result, every new relationship and resource around us is at a disadvantage. Meaningful engagement with whatever is new to us only occurs when we’re pulled past the initial bout of laziness, vanity, and selfishness that accompanies any new experience. Your job is to find a way to reach beyond the surface of every new experience, find its meaning, and express that to the user.

Whatever pulls us past that first 30 seconds is the hook. Don’t think you’re above needing a hook. Nobody is. And, most important, don’t think your prospective customers are above needing a hook. When you see a prompt to “Sign Up in Seconds to Organize Your Life,” it’s a hook. Headlines in newspapers are hooks. Book covers, and their lofty promises like achieving a “4-hour workweek,” are hooks. Dating sites are full of hooks.

An effective hook appeals to short-term interests that are connected to a long-term promise.

Consider your process when purchasing a book. Regardless of how well written and interesting it may be, it is nothing but hundreds of pages — either digital or physical — of black-and-white words. The hook, in this case, is often the cover and title. The cover compensates for the lazy, as it paints a pretty picture that might compel you to reach out your hand and pick it up. Your vanity may be stroked by the prospect of appearing more intelligent or familiar with the zeitgeist by reading what others are talking about. The title and subtitle appeal to your selfishness through the promise of what’s in it for you and your self-interests.

Or consider retail. If you run a store, what you display in your windows determines whether or not a potential customer will walk in. The science of window-dressing is entirely different from in-store merchandising and the quality of your products — but no one gets to feel the thread count of your sheets or the smoothness of your ceramic kitchenware if you can’t get them in the door first.

Your challenge is to create product experiences for two different mindsets, one for your potential customers and one for your engaged customers. Initially, if you want your prospective customers to engage, think of them as lazy, vain, and selfish. Then for the customers who survive the first 30 seconds and actually come through the door, build a meaningful experience and relationship that lasts a lifetime.

Do > Show > Explain

When bringing a new product to market, you’ll be tempted to explain what it is and how it works. Such attempts usually result in extensive amounts of copy, how-to videos, and multisequence digital “tours” explaining the product’s purpose and how to make the most it. For nondigital products and services, explanations take the form of bulky instruction manuals, verbose menus at restaurants, and lengthy onboarding meetings for new clients.

If you feel the need to explain how to use your product rather than empowering new customers to jump in and feel successful on their own, you’ve either failed to design a sufficient first-mile experience or your product is too complicated.

Having to explain your product is the least effective way to engage new users. This realization hit close to home when I joined Adobe and learned how many millions of copies of Photoshop were downloaded every year by prospective customers, opened once, and then never opened again. It happens more often than you think. A new Photoshop document was a blank page, and most people had no idea what to do next. There were no onboarding steps and no templates to choose from first. A quick search for “Photoshop” on YouTube or Google yields tens of thousands of instructional videos attempting to teach people how to use the product, which emphasized how much explanation was required before customers could use the product. There was an entire economy of tutorials, how-to videos, and books devoted to helping prospective Photoshop users navigate the product. Photoshop was a daunting product with no consideration for the first mile.

Over the years since then, the Photoshop team has started designing new onboarding experiences, like a welcome page and tips to jumpstart creative projects. But these attempts to show how to use the product aren’t enough to help new customers achieve some level of success before investing the time and energy to learn how to use the product’s vast set of features.

The absolute best hook in the first mile of a user experience is doing things proactively for your customers.

Once you help them feel successful and proud, your customers will engage more deeply and take the time to learn and unlock the greater potential of what you’ve created. For digital applications such as Paperless Post, an online tool to create and send digital party invitations and birthday cards, that means providing customers with templates to choose from and edit rather than explaining how to create a digital card from scratch. For photography-editing applications like Instagram or Google’s and Apple’s photo products, that means providing smart filters that apply a sequence of effects to an image all at once, rather than forcing customer to learn how to use different tools for contrast, brightness, and sharpness. In most of these cases, full personalization is available—but it’s not the first option.

The same principle applies to physical products and in-store experiences. When educating customers about which products they should buy, activity-apparel company Outdoor Voices, another company I work with, launched “kits” as a way to help their users save time, and do so stylishly. Kits are essentially a preselected set of matching items that help new customers get the basics without having to navigate across multiple product categories and become familiar with a new nomenclature. The customers feel like they’re getting an easy, personalized shopping experience — and the brand is benefitting from fully outfitting them all at once — and they are likely buying a little more than they would have otherwise.

You can’t expect new customers to endure explanation. You can’t even expect customers to patiently watch as you show them how to use your product. Your best chance at engaging them is to do it for them — at least at first. Only after your customers feel successful will they engage deeply enough to tap the full potential of your offering.

Scott Belsky’s book The Messy Middle: Finding Your Way Through the Hardest and Most Crucial Part of Any Bold Venture is available today, October 2, 2018.

Image by Amith Nag Photography / Moment / Getty Images.