Arielle Jackson is Head of Brand and Product Marketing at First Round — for over 10 years, she’s helped hundreds of First Round founders on early positioning, brand identity, launch communications and marketing hiring. She started her career at Google, helping grow Gmail in its early days. At Square, she was one of the first marketers who led the launch of new hardware products. She then joined a seed-stage startup called Cover before it was snapped up by (then) Twitter.

Across all the companies she’s helped, naming is one of the trickiest challenges to solve. It’s hard to find a name, hard to know if you’ve found the right one and hard to know if it’s working. A lot of it is a gut feeling.

Naming exists in this art-meets-science gray area that many founders struggle with. On the surface, it might seem easy, but it’s an exercise in iteration, patience and taste. Search for resources out there and you’re more likely to land on a “name generator” than something that actually helps you come up with a name that feels like it truly fits YOUR company.

So we tapped Jackson to bring some color to the process. In this essay, she demystifies how to select a name — sharing the process she’s used to do it dozens of times. We figured the best person to walk you through it would be Jackson herself. The floor is now hers.

A bad name won’t kill a good company — but sometimes, it feels like it could.

I get why so many founders agonize over picking the right name. You want it to be memorable. You want it to have meaning for your company. You don’t want it to get roasted or outgrow it or regret the decision.

Some of this pressure comes from the fact that an excellent name can only help you, spreading word of mouth and making it easier to build your brand. Yet in many cases, great names don’t start great. Think about Disney, which was simply the founder’s last name: OK name, remarkable brand. In a spreadsheet cell in plain old 10-pt Arial font, would it stand out amongst other options? Probably not. And now, billions of dollars in marketing spend and 100 years later, it’s iconic, synonymous with magic and wonder.

This example should actually take some of the pressure off picking your name; you can’t foresee a decade or a century of brand equity. Think of your name as an ambassador for your brand, not the entire thing. Give yourself the space to “imagine if,” which is what we do around here at First Round Capital.

Naming is one of the most common challenges founders bring to me, usually after they’ve toiled over it themselves, sometimes for months. You can only walk around the block so many times before you get yourself dizzy.

I’ve helped with dozens of names over the course of my career, from companies to products, and I know the struggle founders go through when picking a name that fits their company. So here, I’m hoping to help more founders DIY naming by providing a framework that brings clarity to the naming process: what matters, what doesn’t, some of the legal necessities founders don’t think about and much more.

Incorporating your company: pick something you know will change

There’s a difference between the name you incorporate under and the one you use externally. When you’re first getting started, don’t put too much pressure on your incorporation name because it’s likely going to change. I’d say even plan for it to change.

If you need to act fast, just incorporate using a placeholder name.

Before First Round, I worked at a company called “Apps & Zerts, Inc.” (yes, inspired by this scene from Parks and Recreation). The founders knowingly incorporated under a ridiculous name they would never use publicly. Eventually, once they had confidence in the product they were building and its positioning, we landed on the name “Cover,” filed for a trademark and launched that way. I’ve worked with many founders who have incorporated using placeholder names: the street the co-founders grew up on, a child’s birthday, etc.

My advice is to pick something so outlandish that it could never see the light of day. This frees you up from the agony of selecting the right name (which you can do later), and the more unusable it is, the less you’ll get attached and end up launching with it simply because it’s become comfortable.

You don’t want to get tied to a name because you had to file your incorporation docs on a tight deadline.

A few years ago, I worked with Gagan Biyani, co-founder and CEO of Maven (and previously, co-founder of Udemy) to name the cohort-based learning company. He recommends the patient approach: “We operated for nearly eight months without a name.”

How to pick your actual name

The best time to do this is before launch. No matter how small your company is, once your name is out in the world, changing it only gets harder, not easier — you’re giving up some brand equity (especially if you’ve had the name for a while), there are more places to change the name and more communication required about the change. Do you call it X, or do you still call it Twitter?

I’ve found a few inflection points to be good moments for naming:

- You’ve incorporated using a placeholder name and now you know what you are building.

- You’ve pivoted, and your name no longer makes sense.

- You’ve realized you can’t use your current name for legal or other reasons.

- You’ve outgrown your name. This can happen when the core of what your company does expands beyond its original focus — like Grammarly adopting the name Superhuman after acquiring email platform Superhuman and AI products like Coda.

Expect naming to take at least a month. This isn’t a single brainstorm or ChatGPT prompt.

Creative work is often framed as divine inspiration (and sometimes it is!) but talk to any great painter, writer or musician and they’ll tell you how much unseen labor goes into what often looks effortless. While picking a name is more art than science, having a process results in a name that’s more intentional (and usually better).

Step one: positioning

I’ve gone in depth about positioning on The Review. I recommend starting there, because being able to explain your product in plain English — who it’s for, what it is and what makes it different and desirable — is a great jumping off point for naming it. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- What is positioning, exactly? It’s the space you occupy in the minds of people in your target audience, relative to what they already know.

- The inputs to good positioning: To position your product in the mind of your user requires a bunch of upfront research, from prioritizing audiences to understanding their problems and what they’re doing to solve them. Based on that, you can make a set of choices to avoid being everything to everyone, in favor of being something great for someone.

- The positioning statement: Functionally, you end up with an internal statement that looks something like this:

- For (target customer)

- Who (statement of need or opportunity),

- (Product name) is a (product category)

- That (key benefit).

- Unlike (competing alternative) (Product name) (primary differentiator).

- Here's Maven's first positioning statement, which we used as an input for naming back when they were still using the temporary placeholder “Didactic:”

- For experts (former or current operators) with audiences (5k+ followers online / 500 offline)

- Who want to share their knowledge while making money,

- Didactic is the first cohort-based course platform

- That makes it easy to deliver a premium student experience at scale.

- Unlike small workshops or impersonal mass online classes, Didactic integrates both live and asynchronous components to fully engage your students while eliminating the burden of managing the course yourself.

Step two: complete a naming brief

Once positioning is in a good place, it’s time to set the target on the name itself. It can be tempting to jump right into brainstorming, but without a brief, it feels a bit like throwing darts in a dark room, hoping to hit something.

A simple naming brief ensures the most basic parameters are clear, while also forcing participants to articulate their personal likes and dislikes. Answer the following questions:

1. What are you naming?

The company? The product? Both?

2. What are the names of related / competitor products?

Make sure you don’t sound like everyone else by compiling an extensive list to identify common themes or types of names.

3. Who’s the target audience?

Describe who we’re naming for. Paint a picture of who you’re trying to acquire for the next 18 months as well as who might ever use you.

4. What concept do you want to communicate?

List your brand attributes / personality. How do you want to be perceived? What’s the single most important idea for the name to convey? What should the tone be?

5. Do you have a preference for descriptive, suggestive or fanciful names?

- Descriptive names are fairly explicit about what your business does. Think Internet Explorer, Whole Foods, Toys ‘R Us.

- Suggestive names evoke what your business or product is without being explicit, often via metaphor. Safari suggests exploration. Amazon is a huge river and suggests a wide selection.

- Fanciful names have nothing directly to do with your company’s offering. Examples include FireFox, Adobe, Apple.

- Many people think made-up words can only be fanciful, but they can really be any of the above. PayPal and YouTube are pretty descriptive. Swiffer or Pinterest are suggestive. Oreo or Kodak are fanciful.

6. Pick five company names you really like (which don’t have to be in your specific space). What do you like about them?

Nike, Apple and Tesla often come up during this step. But try your best to separate the name from the company (and what the names have come to mean over decades — see note about Disney above).

7. Now the inverse. Pick five company names you really dislike. What do you dislike about them?

This is obviously subjective, but many founders say they don’t like Hugging Face (too silly), Xilinx (too difficult to produce) or Fast (too generic).

8. Are there any length considerations you need to be aware of?

If you’re a hardware company, etching your name onto a small piece of plastic or metal, space might be paramount. It’s not time for a name like Harley Davidson or The Browser Company, but one like Oura or Ember.

9. What are the legal considerations?

Some founders are adamant about owning the trademark to their names, but others don’t care as long as they’re not violating someone else’s trademark.

10. Does the exact domain name need to be available?

Consider alternate top-level domains (TLDs) besides .com, and if you’re willing to amend your name with a prefix or suffix to make it work for the domain (we’ll get into this more later).

11. What is your rough budget for domain acquisition?

This is where I usually have to come in with a reality check. If you want a real English word on a .com, it’s going to cost you.

12. Any additional details, requirements or inspiration we should be aware of?

What existing ideas or concepts do you have already? What should we avoid? Is there anything else we need to keep in mind? For example, I’ve worked with founders who have their operations split between the U.S. and China and needed the name to be easy to pronounce by a native Mandarin speaker.

Step three: have a namestorm

The best brainstorms combine structure and creativity. Without some structure, it’s easy for creative ideas to be untethered and unhelpful. Establish the box before thinking outside it.

Too often, founders brainstorm alone or just with their co-founder, which vastly narrows the pool of good ideas. While that can be a good starting point, you’ll definitely want to bring in other employees or even friends and family. If you happen to have a linguist friend or a writer or someone who speaks five languages, this is the time to call in a favor and get them to participate.

You’re probably thinking AI can be great at coming up with names. In my experience thus far, the overt name suggestions haven’t been good (they’re either obvious and pattern-based or unusable) but the brainstorming has been amazing. Instead of spending hours reading Wikipedia and searching, I have a conversation with an LLM:

- Bad prompts look like this: “Come up with a name for my startup that makes engines,” or “Provide 10 names for a company that does therapeutic services for children in a preschool setting.”

- Good prompts are more focused on identifying the specifics you need without the hours of legwork: “What are 25 lesser-known engine parts? I’m looking for real, technical components that aren’t as widely known as ‘turbine’ or ‘compressor’ but are important to the function, efficiency, or durability of gas turbine engines.” Or “Give me 10 kid-friendly English verbs that mean ‘to propel’ and 10 nouns that suggest forward motion, like a slingshot or swing.”

I’ve covered some of the brainstorm process in this positioning article, but let’s get into some more detail.

1. Take your positioning statement and break it into nouns and verbs.

This is a great warmup exercise to get the creative gears greased. For every meaningful word you isolate, create a full list of synonyms, antonyms, free associations, words in other languages, etc. You can use AI to help with this, and just capture as many as you can.

Full disclosure, it’s unlikely you’ll find your name this way, but it happens. When I was working with Maven’s co-founders on their name, we first found “maven” (from the Yiddish word “meyvn” which means “one who understands”) when doing this for “expert” — one of the words straight from their positioning statement.

2. After the warm up brainstorm based on your positioning statement, do a second brainstorm on ~8-10 relevant themes.

Here are some of the themes we played with when naming Maven:

- Groups of people or animals (herd, flock)

- To gather or gatherings (squad, audience)

- Patterns in fabric, math or woodworking (joinery, fractal)

- Last names of famous educators (Montessori, Nye)

- Ancient Greek words and mythology related to gathering or learning (agora, Socratic)

- Special or premium access (red carpet, box seats)

One theme I like to include is “just say it:” explain what the heck the company does in as few words as possible (think PayPal or even First Round).

3. Read — a lot

The Review team recently sat down with Jeanette Mellinger, former Head of UX Research at Uber Eats and BetterUp and now, advisor and consultant to early-stage startups on all things research. Her research framework includes an “incubate” phase for a reason: “Look at how our brains work. Great ideas don’t happen on schedule. True insight takes time, and pops up in unexpected ways.”

While you’re researching terms related to your chosen themes, there are many other ways to spark ideas — like reading historical accounts of the industry or browsing everything from baby name websites like Nameberry to Urban Dictionary (I’ve found name contenders on both!).

It also helps to read fiction or nonfiction that has nothing to do with the topic at hand. Highlight or write down names and phrases that are interesting and could be food for thought. I get kind of obsessed with words when I’m in this phase of naming and pay attention to everything from street signs to song lyrics.

Sometimes inspiration comes from somewhere unexpected. For example, wifi system eero was originally called “Portal,” but while working with naming firm A Hundred Monkeys, someone mentioned that they were from St. Louis, which led to discussing the city’s famous Gateway Arch by Finnish-American architect turned industrial designer Eero Saarinen. That moment led to a new name reflecting the company’s focus on design.

I consider this to be a different and equally useful path from the AI research you’re doing; it’s more serendipitous than the pattern-based AI suggestions.

4. Gather every idea in a spreadsheet and make a shortlist.

At this point, you should have hundreds of ideas at minimum. Maybe even thousands. Scour the earth. To expand your list, play with the following types of names:

- Real words: like Apple, Gain and Square that have been repurposed outside of their definitions

- Phrases: like Man Repeller, Good Inside and Human Interest

- Affixes: tacking something onto an existing word, like Blogger or Contently

- Compounds: two words fused together, like Salesforce or Facebook

- Blends: part of one word combined with part of another, like Pinterest (pin + interests) or Microsoft (microcomputer + software)

- Fragments: a piece of an existing word, like Cisco from a clipped version of San Francisco or Vanta from advantage

- Misspellings: like Google, Lyft and Okta

- Other languages: like Reebok (from "rhebok,” Afrikaans for a South African antelope) or Asana (Sanskrit for a sitting meditation pose)

- Onomatopoeia: words that imitate the sound they represent, like Zoom and Twitter

- Coined words: fully invented words like Kodak, Etsy, or Vercel. Beware: the failure case here is sounding like a little-known Pokemon creature (think Zygarde or Giratina) or a drug (think Ozempic, Abrysvo or Camzyos — there are a lot of strange coined pharmaceutical names due to intense trademark and regulatory pressure)

- Names of people or places: like Tesla, eero and Duane Reade (the first location was on Broadway between Duane and Reade Streets)

- Eponyms: named after the founder like Disney, Adidas and Ford

- Acronyms: like IBM (International Business Machines), GEICO (Government Employees Insurance Company) or Fiat (Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino). Some of these you may have not known are acronyms!

- Alphanumeric: like 7-Eleven, from their original hours of operation, or 23andMe from the 23 pairs of chromosomes

Then, go through and highlight the ones that are interesting and worth pursuing. Some practical criteria to consider:

- Trademark. Is the name OK to use? Meaning, it’s not violating someone else’s trademark (bonus if you can proactively trademark it yourself).

- Domain availability. Is there a path to a viable domain?

- Distinctiveness. Is it unique and memorable?

- Timelessness. Is it cool now and will it still be cool in 10 or 100 years? You don’t want to be dated based on the name you pick when it’s no longer trendy anymore (think the “drop the e” trend of Tumblr or Flickr or Grindr from the 2000s — Twitter was originally part of that group but they later added the “e”). You want a name that will age well because it's built on deeper linguistic, semantic, and/or emotional foundations.

- Reflective of key messaging. It’s nice if your name can do some marketing work for you. Is it at all suggestive of what the product does or a feeling you’re trying to convey?

- Sound and ease of pronunciation. Is it easy to spell? Is it easy to understand over the phone? This is more important than people think. Say the name out loud. Is Zapier “zay-pee-er” or “zap-ee-er”? Think about how it would be used in a sentence and say that out loud too. Does it feel natural in your mouth as you say it? Is it fun to say?

- Appearance. Literally how pleasing or logical it looks to the eye. Names with harmonious letter heights, shapes and symmetry give designers a field day when creating wordmarks. Think Coca-Cola with those twin “C”s and “a”s.

- Length. A two-syllable word can be preferable because it’s not too long but more distinctive than a monosyllabic one.

Using those criteria and any additional ones you added to your brief, make a shortlist of 10-25 contenders. I find it helpful to put these into a new tab of the spreadsheet, where each name is a row and the criteria are columns — then, for every name, assign each consideration a stoplight color.

5. Narrow it down to a top three

From your initial shortlist, get to your top three. I usually have each founder independently send me their top three, and then we get together to discuss what emerges.

Often, practical considerations like trademarks and domains will help you declare a winner. If not, here are some other signs to help you whittle down.

Good signs:

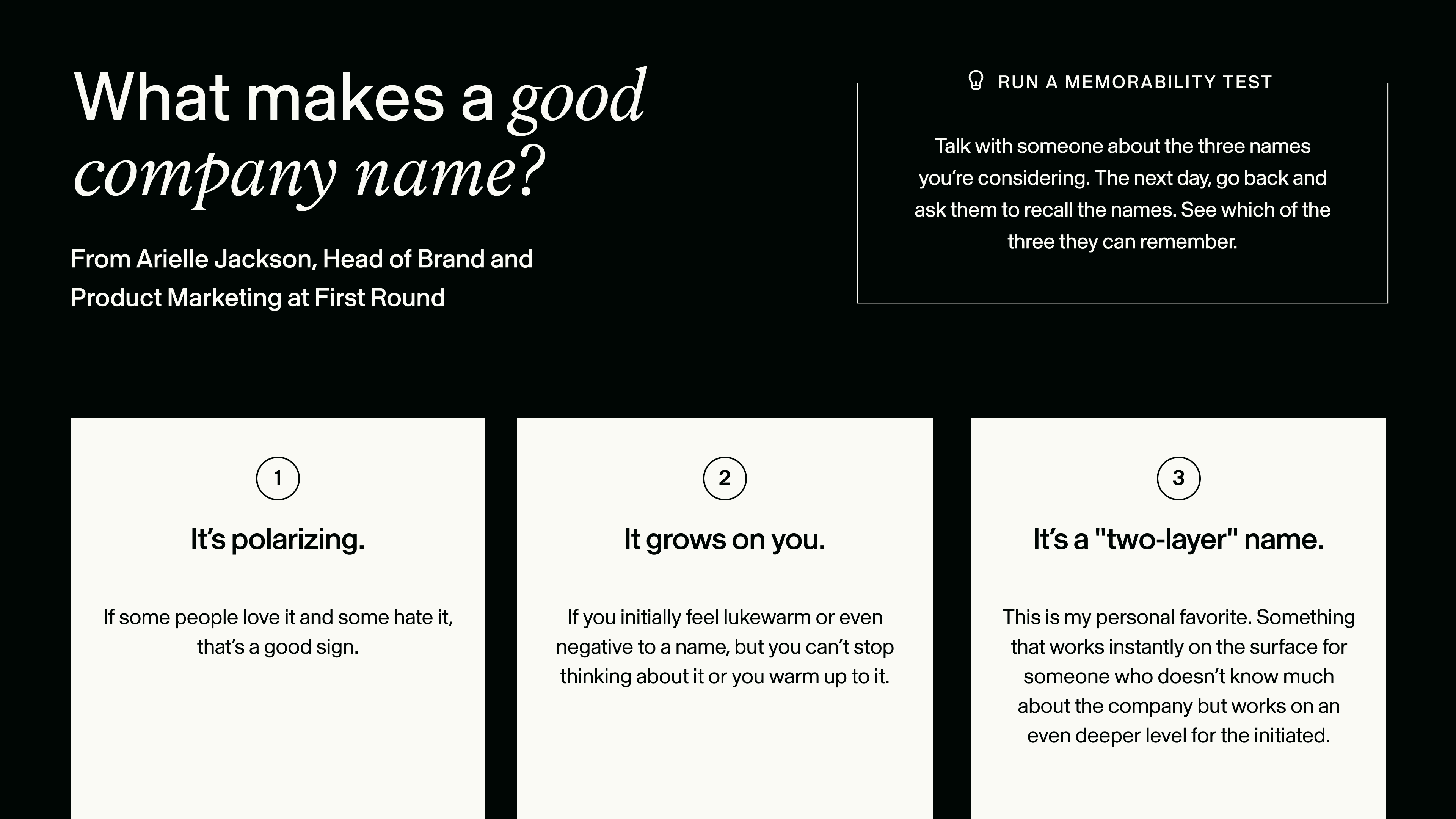

- It’s polarizing. If some people love it and some hate it, that’s actually a good sign. The names that everyone thinks are fine but no one loves are the boring, safe choices. You’re looking for names that get a reaction. It means people are feeling something.

- It grows on you. You initially felt lukewarm or negative to a name, but you can’t stop thinking about it, or you warm up to it. Nike is a classic example, which at the time was called Blue Ribbon Sports. As detailed in co-founder Phil Knight’s memoir Shoe Dog, when an early employee suggested the name Nike (after the Greek goddess of victory), Knight thought it was “not terrible” but didn’t love it. After it was picked from an “unspeakably bad” list that included Falcon and Dimension Six, Knight later admitted, “it grew on me.”

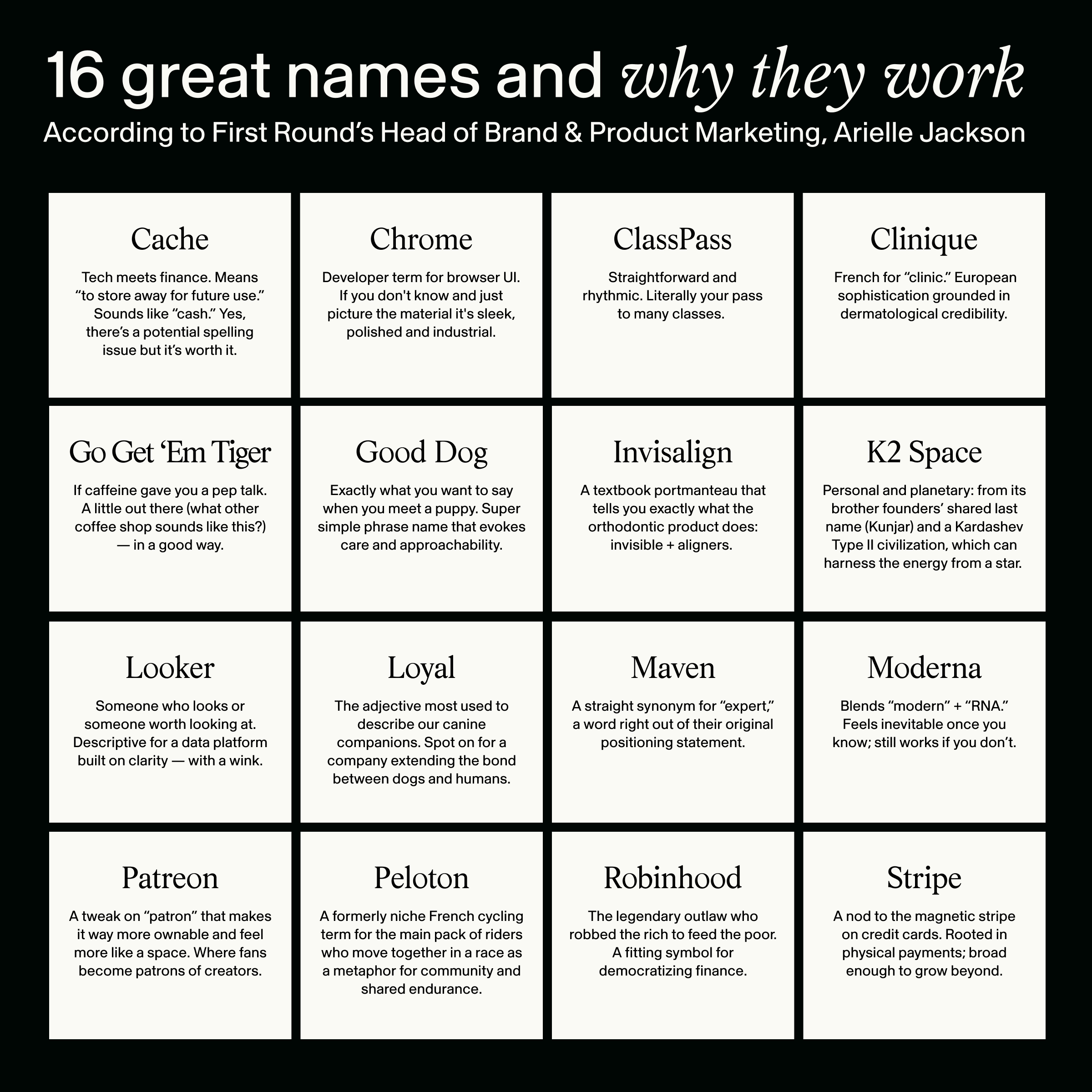

- It’s a “two-layer” name. This is my personal favorite: a name that works instantly on the surface for someone who doesn’t know much about the company, but works even better on a deeper level for the initiated. For example, most people think Google is a made up word that’s fun to say. But math nerds know it comes from the mathematical term “googol,” a one followed by 100 zeros. Or Moderna, which just sounds like a modern biotech until you know it’s a blend of “modified” + “RNA.” If you’re in the inner circle, these names feel like they’re winking at you.

Bad signs:

- There are tons of companies with the same name or it sounds like a competitor.

- It’s obvious and boring.

- It can easily be made fun of. "Pilaster" came up recently in a brainstorm. Say it out loud a few times. The jokes would write themselves.

- It locks you into something that’ll feel too restrictive later. When ZenPayroll started to add products outside of just payroll, the name got too small — so they rebranded to Gusto.

Getting feedback on your contenders

Naming is obviously a qualitative exercise. To me, good naming lives at the intersection of instinct and discipline. When things click, it feels obvious, like the company named itself. But many founders, by nature, like to test and get feedback and measure as quantitatively as possible — so often, they’ll look to their internal teams or friends and family or customers or generally, “the internet” as a backboard off which to rebound ideas.

Research around naming is tricky, particularly quantitative or survey-based research.

If you ask a bunch of people to help pick a name, you’re likely to end up with a least common denominator name: one that pleases everyone but means nothing.

However, this type of research can be helpful to surface negative connotations you weren’t previously aware of. An example here is Vicks, the over-the-counter medication. In Germany, they’re “Wick” because in German “V” can sound like “F,” so it sounds like “Ficks” to German speakers — which is a vulgar term (that many of you are probably looking up right now).

It can also make you aware of other meanings or associations you may want to play up as you’re developing the brand. If a name doesn’t communicate anything, that’s also good to know — and it’s probably not a good name.

On the qualitative front, I’ve found it helpful to gather feedback from both initiated and uninitiated users:

Talk to current users.

Tell them you’re exploring a few new names, and ask what each name communicates. You want to uncover each option’s strongest qualities and find those negative associations that become dealbreakers.

Then ask which name they think fits best and why. Beware that this question often results in a descriptive name. I’ve found that in general, people are fairly literal and tend to prefer things that are familiar, so for a browser, that means they’d choose Internet Explorer over Chrome, Safari, or Firefox. Follow up with why they picked that name to get a deeper explanation of their choices.

Talk to uninitiated users — people in your target audience who don’t know anything about the product yet.

Two options here:

- Same as above, but first using your positioning statement as the foundation, write a very short blurb about what the product does and have people read it with an “X” as the name. Then show the 2-3 names you’re deciding between.

- Show each name by itself and ask folks what the name brings to mind and what they think a product with this name might do.

Run a small memorability test.

Memorability is an important aspect of a good name, but it’s also difficult because the human brain is a weird thing.

Conflicting elements can make a name memorable. One is concreteness, when a name evokes something tangible and easy for people to picture, like Apple or Red Bull. That mental image helps people remember the name, even if it has nothing to do with the product itself. These names often take something simple and familiar and place it in a completely new context — think Shell for gas or Caterpillar for tractors.

However, names can also gain memorability through functional relevance — when they directly reflect the product promise. HotelTonight is overtly descriptive, while Swiffer succeeds more subtly: it sounds like swiftly sweeping, embedding the product’s benefit in its phonetics. Another path to memorability is wordplay, which can make a name catchy or fun to say. That might be through alliteration (Firefox, Coca-Cola), rhyme (7-Eleven), creative misspelling (Lyft), or even palindromic symmetry (Sonos). And just to make things extra confusing: being short and sassy with a name can make it memorable (like Sony), but so can being long (like American Express or Harley Davidson).

I like to run a simple test: talk with several people about the three names you’re considering. The next day, go back and ask them to recall the names. See which of the three they can remember.

Trademarks and legal clearance

Congrats, you have your top choice name. Before moving forward — using it publicly, doing visual identity work, spending a five-figure sum on a domain — you’ll want to make sure the name is usable. Don’t fall in love with something you can’t have.

I highly recommend having a trademark attorney involved at this point. There are essentially two questions to address (everyone needs to answer the first one):

- Might you be violating anyone else’s trademark? If so, you could receive a cease and desist and be forced to change your name.

- Can you trademark the name yourself? If you can, I suggest doing this — it’s relatively low cost ($5k) and proactively prevents others from using your name.

Just because another company uses the same name doesn’t mean you can’t use it. Think Delta (airlines, dental insurance and faucets), or Dove (soap, chocolate). These can coexist because they’re in unrelated industries with very different goods and services — so there’s no likelihood for user confusion, which is something both you and the trademark office want to avoid. Contrast that with trying to use the name Dove to make a different kind of chocolate, or even a different kind of candy. That could be a problem. You want to be as distinct as possible from others offering similar goods and services.

Trademarks are categorized into classes by the USPTO, based on the type of goods or services they cover. For example, Class 9 is for “Electrical and scientific apparatus” which includes downloadable software and mobile apps, but not SaaS. That falls under Class 42, “Computer and scientific services.”

A company can hold trademarks in multiple classes if its products or services span different categories. For instance, Anduril has registrations in several classes — including both 9 and 42 but also Class 7 (machinery), Class 12 (vehicles), Class 23 (yarns and threads), and more. Within each class, you must specify a “description of goods and services,” which precisely defines what your trademark protects within that category.

Some common steps for clearing use and protecting your name are:

- Start with a basic search. You can do this initial screen, sometimes called a “knockout search,” either yourself or with an attorney here at the USPTO to quickly rule out obvious conflicts.

- Do a comprehensive search. This goes beyond registered trademarks and includes common law uses — businesses using a name without having registered it. A trademark attorney or specialized search firm can run this type of report. It takes longer because it includes unregistered but legally relevant uses like domain names, social handles and state business registrations.

- Understand the risks and your tolerance. Usually, names come back from your legal advisor as low, medium or high risk. Get on the phone with your lawyer to discuss the results and strategize. Don’t email — it’s much better to talk about these things over the phone because lawyers will be more likely to give you brass tacks they might not be comfortable writing.

- Decide whether to file. If you do, you’ll need to determine the relevant trademark class(es) and draft an accurate description of your goods and services. Again, a lawyer can help and actually do this filing for you. You can file for a word mark (text only), a design mark (logo), or both. In the meantime, you can likely start using your name.

- Wait. For months. You (or, ideally, your trademark attorney) will eventually receive either an approval for publication or an “Office Action” from the USPTO, which is a notice requiring a response. For example, if your name is initially found to be confusingly similar to another, your attorney can help you amend your application or submit arguments to overcome the refusal.

If you’ve incorporated as a different name

Keep in mind that if your company was incorporated under a different name than the one you plan to use publicly, you’ll need to make that official. To do this, your lawyer can either amend or restate your incorporation documents to reflect the new name, or file a “doing business as” (DBA) which legally allows you to operate under a trade name that’s different from your registered corporate entity.

Think of a DBA as your company’s official nickname — the name you go by in public even though your legal paperwork uses another. We did a DBA at Apps & Zerts. Maven updated their corporate entity. There are pros and cons with either path. I leave it to the lawyers to decide.

This advice comes directly from one:

“Changing the name on the corporate side is straightforward – it just requires Board and stockholder consents, and an amendment to the certificate of incorporation that gets filed in Delaware.

You also need to update the IRS – they can be painfully slow in confirming the name change, and sometimes that can create some administrative burdens with third parties such as payroll providers, banks, insurance companies and importers, who frustratingly sometimes insist on something more than the Delaware corporate filing. The fastest way to cut through that is by filing the tax returns with the new name reflected.

Using a d/b/a has its own set of hassles – technically you’re often supposed to register that in local counties/cities wherever you do business, which can be a real pain to keep track of as I believe there are periodic filings in some places every year or every 2-3 years.”

Domains

Get the name right, then solve for the domain.

It’s harder than ever to get a good .com domain — but it also matters less than ever. User behavior has shifted away from direct URL entry and toward search bars with predictive text, social media and apps.

Plus, folks are far more comfortable with a variety of domain extensions beyond .com.

You can get creative with the domain you select by using:

- Prefixes — variants with a word in front of the name like onepeloton.com or tryfigma.com (they moved to figma.com later).

- Suffixes — variants with a word in the back of the name like awaytravel.com or squareup.com (they have a redirect in place from square.com but even today that’s still technically owned by Square Enix, the Japanese gaming company).

- Alternative top level domains (TLDs) — .ai is an obvious one for today’s founders, but there are others like .aero or .university you might consider depending on your company. An .ai domain might cost you five figures. The same domain at .com might be seven or more.

In Maven’s case, they wanted maven.com, which was owned but no longer being used by a big corporation. Eventually, they worked out a part-cash, part-stock deal to acquire the domain. Biyani wrote about their path to Maven a few years ago.

If you can’t outright purchase your domain, a domain broker can help you negotiate if the domain you want is owned by someone else. They can also help structure lease-to-own options, where you rent a domain for a set period of time with the option or obligation to purchase it at the end of that term. This spreads out the upfront cost and reduces some of the risk with going all-in on a domain.

Stop to ask yourself: Does the .com really matter to you? One founder I worked with spent $39 by amending the name, while another spent a seven-figure sum on the straight .com because they thought:

- The .com communicated more trust to their small business customers, which was important given their industry.

- Buying the .com name felt inevitable as the company hopefully became successful.

- If they spent ~$1M a month on search ads, the .com domain would have a large overall impact on conversion rate and eventually positive ROI.

Some founders just don’t have cash for the straight .com or think it’s prudent when they’ve only raised a few million dollars. It’s quite common to start with a variant and kick .com down the road. Or if you’re a mobile app, and most of your user acquisition comes from app stores, it matters much less. All of this really depends on the context of your business and some personal preference.

Naming your product vs. naming your company

When it comes to naming products, most founders overcomplicate it. My advice: Don’t get too creative. If you only have one product, keep the company and the product name the same. When you branch out into multiple offerings, then it makes sense to ask customers to remember more than one name. As a fledging company it’s hard enough to get them to remember one.

If you’ve built equity in your company name, resist the urge to give your product an entirely different name. It’s a lesson some of the frontier AI labs seem to have missed.

I’d bet the average users of ChatGPT have no idea it comes from OpenAI, or that Claude comes from Anthropic. And I don’t think that was intentional.

When you are launching a new product and need to disambiguate it from the company name and/or your first product, a simple framework usually works: [Company Name] + [Descriptive Word]. This lets the new product borrow the parent brand’s equity and build on it.

It works best when the company name itself isn’t also descriptive. Google Maps is a good example. By the time it launched, Google already stood for search, speed and simplicity in “organizing the world’s information.” There was no need to get cute or abstract — these were maps, done the Google way.

Of course, there are times when separating the product name from the company name makes sense. Google kept its name attached to its products (Google Maps, Google Drive, Google Calendar) until it introduced Android. They didn’t acquire Android and rebrand it to Google OS or Google Phone; they kept the distinct name that felt open, neutral and futuristic. This new mobile platform was supported by Google, but not defined by it. Square took a similar approach with names like Square Reader, Square Register and Square Invoices. Then it launched Cash App, a consumer product aimed at a completely different audience that might never touch its merchant tools.

Some car brands use model numbers to lean on the parent brand (BMW’s X5, Audi’s A3). Others use distinct product names (Toyota’s Prius, Tacoma and more) to create a new set of expectations and associations for each. For now, just remember: descriptive product names reinforce who’s behind the products; distinct product names provide room to build something new.

If you’re still struggling with naming

When you first started with naming, you might’ve thought, “How hard could this really be?” Sure, you could pick a name out of a hat — but choosing the right name that works for your company requires a much more thoughtful process.

If you don’t want to go through it, you can outsource to a specialized naming firm, or in some cases, your branding agency can take over. But keep in mind, it’ll cost you: full service naming usually starts around $25k but can go all the way up to six figures.

Really, my hope is that this essay might make it possible for more founders to DIY naming. There are other DIY resources that can help too, like a fun deck of cards for name generation (put out by a naming studio I’ve mentioned working with called A Hundred Monkeys). Or if you’re more of an auditory learner, listen to naming expert David Placek of Lexicon Branding on Lenny’s Podcast. Don’t forget about your marketing friends or your VC firm that might have an in-house marketer — they can act as your thought partner.