Tomer London’s father gave him just one piece of career advice: don’t start your own business.

“For forty years, my dad has owned a small clothing store in Haifa, Israel, where I grew up. From a young age, I noticed how emotionally difficult it is. I could tell within seconds of him getting home if it was a good or bad day.”

London spent years helping out at the shop after school, cleaning, answering phone calls, handling customers and organizing inventory, and despite his father’s warning to become anything but an entrepreneur, it was too late. At twelve, he decided to bring his dad’s pen-and-paper inventory system online. Armed with a 386 PC running Windows 95 and a brick-sized Visual Basic guide, he taught himself to code and built an inventory management program for the store from scratch.

“It worked really well, saved my dad a bunch of time — he ended up buying a computer for the store just to run it,” he says. “That connection with small businesses meant that once I started touching software, I wanted it to do something useful.”

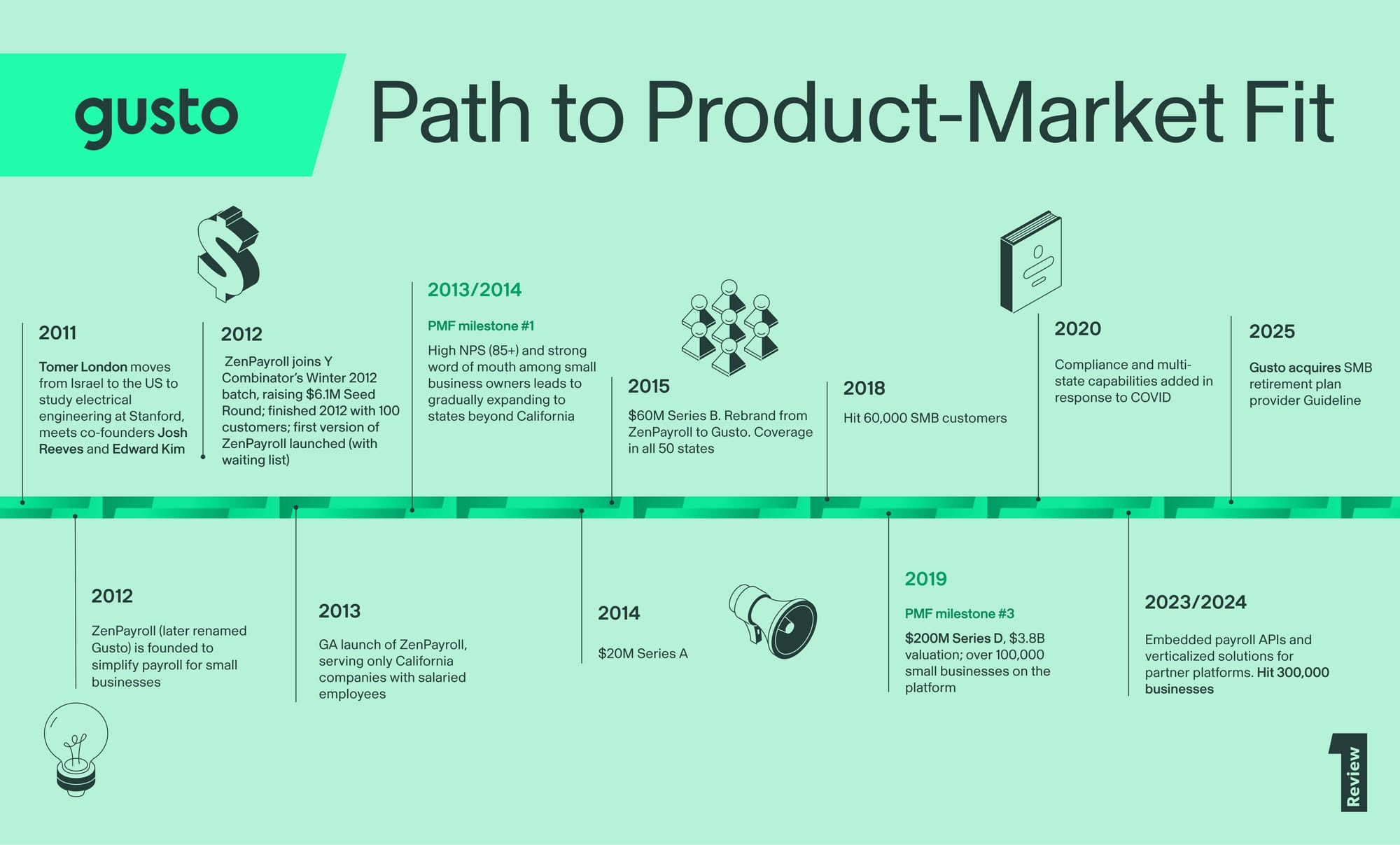

A decade and a half later, London arrived at Stanford for a PhD in electrical engineering, where he met future co-founders Josh Reeves and Edward Kim. The trio joined Y Combinator’s Winter 2012 batch, launching Gusto (then ZenPayroll) with a simple mission: to take the complexity out of building a small business, starting with payroll. What began as a narrow payroll product for California small businesses has since grown into Gusto, a platform that helps more than 400,000 small businesses manage payroll, benefits, HR, and compliance, most recently valued at $9.5 billion. Gusto’s latest milestone is its acquisition of Guideline, which Gusto has partnered with since 2016 to provide 401(k) services to SMBs.

In this conversation, London reflects on how years of building, failing, and trying again sharpened his judgment as a founder, teaching him to seek rejection to learn faster and recognize the emotional signals of real demand. The instincts that began in his father’s shop — listening closely, solving real problems, and caring about how the work gets done — still guide how he builds today.

Pressure-testing ideas through early customer discovery

It’s 2012 and Tomer London has locked himself in a walk-in closet, phone in hand, to dial the numbers of small business owners he finds on Yelp, taking rejection, after rejection, after rejection on the chin.

It’s been more than fifteen years since he built that inventory program for his father’s clothing store. He now calls the Bay Area home, as an electrical engineering student at Stanford. London had been studying in Israel and founded a handful of small software startups that ultimately didn’t scale. He decided to apply for a U.S. student visa, inspired by the story of the Google founders meeting at the university, as well as watching a video of Steve Jobs’s 2005 commencement speech. Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you, is the line that stuck with him.

Not long after arriving on campus, London made the kind of connections he’d been seeking in Josh Reeves and Edward Kim. “I was really, really lucky meeting Josh and Eddie in my first few months at Stanford,” he says. United by their shared desire to solve problems with software, the three students soon began exploring how to simplify payroll, and those early brainstorming sessions would become the foundation for ZenPayroll.

Which is how he found himself in that closet.

“I’d just start calling potential customers, one by one,” he says of the early days of customer discovery. It’s a strategy he recommends to all early stage founders. “Every day you can pitch something a little bit different,” he says. “You learn from the day before.” It was the fastest way to figure out what worked; talk to people, see how they react, tweak, repeat. “Having multiple founding journeys — me, Josh, and Eddie all had previous startups — helps you avoid repeating the same mistakes,” he says. “You can move faster, validating or invalidating ideas. It builds confidence. You have very little to lose.”

London leaned on being a student, and a foreigner, to disarm skeptical business owners, from laundromats, to convenience store owners to veterinary clinics. “I’m a PhD student from Stanford and I have a few questions,” he’d begin. “Do you mind helping?” Or, “I’m not from here, can you explain to me what this means?”

“You’d be surprised how many people are excited to speak with technologists who can build things for them,” he says. “Most people outside of Silicon Valley don’t often get to speak with people that can build products they use everyday.”

For London, there’s no shortcut to proper customer discovery. “It’s hard, but it’s your job to speak with strangers,” he says. “Fear of rejection is very human, but when you speak with a customer, you need to be in the mindset of seeking it.”

You go out there to learn, and the learning comes from rejection. You’ve got to develop a thick skin.

The art of customer discovery, London says, is patience and persistence — using every conversation, especially the rejections, to deepen understanding. “The world is full of distractions, long to-do lists, and things people care about,” he says. “It’s quite rare to get to that place where you feel excitement and energy from a potential customer. When you find it, stop everything, and double down.”

A strong signal from SMBs tightens Gusto’s target customer

They continued building the business, acquiring early customers through more relentless cold calling. “We were hustling, trying to find who would trust the three of us to run their payroll,” London says. “We had a swimming class for kids. We had a flower shop where Eddie was buying flowers, and he asked her, ‘Who do you use for payroll?’ She didn’t have a provider, so we set her up.”

They were also concurrently exploring building an API payroll product for enterprise platforms. “I remember going to some of these big platforms and we were sure they were going love it,” he says. “We were solving a really complicated problem for them. But mostly the response was, ‘This could be cool, but it’s not a priority right now.’”

It was this early feedback that reinforced their focus on SMBs. “When we talked with a small business, it was clear they were craving something better,” says London. “The pain from payroll was across industries, and the pain was strong enough that even if we did not have a personal network with dentists, dentists loved Gusto.”

The founders had recognized the “positive tension,” that unmistakable pull from SMBs who urgently wanted what they were building. It’s another lesson London gained from those early ventures he started in Israel: how to know if you’ve truly found product-market fit.

“It should feel like pulling a rope, not pushing a rope,” he says. “With my previous company, I remember going to one of the biggest companies in Israel, an airline, and trying to convince them, ‘Here’s how the product is going to make your life better, and your customer’s life better, and improve your metrics.’” But London didn’t feel that positive tension. “There was interest, but it was not a priority for them. It was a priority enough to keep getting us more meetings — but not enough to actually get a contract.”

He also looks for emotional reactions. “A lot of people, when you tell them about your idea or show them the product, will be polite and nice about it,” he says. “But ‘polite’ and ‘nice’ is not how you build a business. You need a strong positive emotion — or a strong negative emotion.”

It’s the intense reactions on either end of the spectrum that London found valuable, whether critical or positive. “When someone says your stuff is absolute shit, that’s gold. There’s something in your mental model that’s wrong; either it’s the wrong customer, or something about your service, or the way you pitched it.” And on the flip side: “When someone is emotionally reacting with engagement and excitement — ‘Where can I sign up?’ — you know you’ve hit gold. But 90% of conversations sit in the middle. There’s not a lot of data there.”

London says a founder should understand their target audience so well that when you talk to customers, you should know how they’re going to respond before they open their mouth.

Speak with customers so much that you start predicting what they’re going to say next.

London estimates that in those early days, two out of ten SMB owners they spoke with were instantly sold. “That’s great product-market fit,” he says. “The next step was to figure out, who are those two? Who are those segments? Then you can pick ten of those, and you’re going to get ten out of ten.”

The company eventually applied to YC and got in, which again brought into question the market segment they’d focus on — even though they’d been committed to building a payroll product for SMBs. London debated with Reeves and Kim about which market sector they should target.

“I actually thought we should focus on startups,” he says. They could tap their YC batch mates. “We could just go to them and say, ‘Hey, do you have payroll? No? Great, do you want to use us for it? I can onboard you right now.’ But Josh pushed to go broader, to put it out there for all small businesses. That ended up being the right call.”

As they moved through YC and started raising their seed round, they encountered a new kind of skepticism. “Investors didn’t believe the story of what we were trying to build,” London says. “There’s a reason why back then there were tons of companies focusing on software for enterprise, and software for consumers; for SMBs, you can’t just put it on billboards.” The SMB audience is fragmented, made up of millions of independent buyers with needs too highly individualized to be effectively reached through broad, top-down marketing. Not only that, but each account would bring in far less revenue than an enterprise business or a fast-growing startup would. In other words, most investors saw small business go-to-market as a losing game.

But the trio remained steadfast in their commitment to SMBs and to test it, got hyper-focused about which types of SMBs they’d focus on. This was the thinking behind their decision to target a specific segment of the market within SMBs: California companies with salaried employees only. “We decided that we were not going to serve anyone else,” London explains. “Because we wanted to make sure that every person we did serve loved the product.”

They aimed for an NPS of 85 and above, knowing the power of word-of-mouth. “Small businesses often have friends who are small business owners. Our hypothesis was, ‘We’re going to build a product and service people love so much that small businesses are going to talk about it all the time.’”

Letting customer insight drive the roadmap

In the early days, London and his co-founders found a rhythm that kept them moving quickly: a strict monthly release cycle. “The way we built the first product was around releases — we had a monthly release cycle,” London says. “We were all working together in one small room. It’s not like we’d start working and only see each other at the end of the month, but having that monthly cadence meant we were always building backwards from a clear goal.”

Each month they forced themselves to answer the question, what needs to ship by the end of this cycle? From there they worked backward, scoping and prioritizing the most impactful features. “By the end of this month, here’s what we need to ship. Now let’s figure out how to do it in the time we have. There’s no other way,” London says. “That approach forced us to be decisive about scope — what to build first, what could wait. It helped us make progress really fast.”

This disciplined cadence helped fuel the young startup’s momentum. “This was post-YC, during that first stretch of about a year,” he says. “Every single month was about defining the thing we needed to ship to reach our goals. It was really helpful.”

As they were onboarding customers, London’s upbringing as the son of a shop owner came through in his hands-on, service-first approach. “This first set of customers all had my phone number,” he says. “I personally onboarded every single employee at every one of those first, I want to say, fifty companies. It was an incredible experience to learn what works and what doesn’t. You see them use the product, see what’s confusing, write it down, then go and fix it. You get a bunch of insights from that that can really help build a better product.”

It would take nearly a year before the product could handle full self-service, letting customers onboard, run payroll and file taxes on their own. Until then, every interaction ran through London or one of the co-founders. It was a high-touch, time-consuming approach, but worth it.

Even once they’d launched publicly — about eight months after YC, with a TechCrunch announcement tied to their $6.1 million seed round — the mix of customers remained split between startups and small businesses. By that point, they had already begun expanding beyond California, rolling out state by state as customer satisfaction remained consistently high.

With customer satisfaction consistently high, they decided the time was right to start expanding beyond their California test market — the narrow focus that had allowed them to perfect the experience and build genuine customer love. They began by adding support for hourly and contract workers, not just salaried employees, and rolling out state by state. “The timing was 100% based on how well the payroll product was doing,” London says. “It felt quite linear. We knew what we needed to do. We needed to expand states, we had a list of features and functionality, and I knew we could do it.”

As adoption grew, in 2015 ZenPayroll rebranded to Gusto, a name chosen because it conveyed the enthusiasm, care, and human warmth they wanted people to feel when using their product — a stark contrast to the cold, bureaucratic baggage of “payroll.” “When we thought about our mission, it was never just payroll,” London says. “Payroll was where we started, but it was clear after a while that payroll data is very, very powerful. Once you’ve done payroll onboarding, you know everything about the company: who the employees are, where they work, how much they get paid. That makes it really easy to add additional products and solve more problems.”

The first new product was benefits, followed soon after by insurance and HR tools. “Health insurance back then felt exactly like payroll felt — people hated the experience,” London says. “It felt janky. You had to call people, fax forms, do a bunch of manual work. So we thought, can we just make that a few clicks instead?”

London validated the idea the same way he had in the early days — talking directly to customers. “I remember sitting in a room and calling twenty of Gusto’s customers that I thought could be a good fit,” he says. “I pitched them: ‘Hey, we’re going to build this. Here’s how much it’s going to cost. Can I sign you up?’ I got seventeen out of twenty.”

The overwhelmingly positive response confirmed they were on the right path. “It represented this combination of a really important pain point and a great revenue stream,” London says. “We were at a point where payroll was going well. The team was executing, we were expanding state by state. We knew we could take some of our best people, put them on a new team, and launch something from scratch.”

That was the beginning of what Gusto’s founders called the “people platform”: a suite of products that would help small businesses streamline employee services beyond payroll. “When we did our YC pitch, the last slide was about that,” London says. “It said, ‘We’re starting from payroll, the next step is benefits and HR, and from there it’s going to be a full people platform. Everything to help you start, build, and grow your business.’ That was the vision from day one.”

Then, in 2020, when the pandemic hit, compliance became a focus. “We heard a lot about it over the years,” London says, “but it really popped up in COVID. All of a sudden, a company with seven employees might have five different states to manage. There’s a lot of compliance work around managing the state entities, the registrations, all the different tax regulations — every state is different.”

The pandemic, as painful as it was for small businesses, also uncovered an opportunity for Gusto to better support them. “It completely changed our prioritization,” London says. “We brought compliance up to the top of the roadmap, and we’re spending a lot of energy on it now. I think we have a really good product there.”

For London, it was another reminder that the company’s best product decisions have always come from listening to customers — the same instinct that started in that walk-in closet a decade earlier. “That’s something I wish we’d seen earlier,” he reflects. “Compliance is absolutely part of the job people hire Gusto to do. It’s not an add-on. It’s central.”

Looking ahead

In August 2025, Gusto announced plans to acquire Guideline, bringing in-house the 401(k) service the two companies had partnered on since 2016. It’s a milestone that marks how far Gusto’s “people platform” vision has come. But for London, it doesn’t feel like a finish line.

“When I look five years ahead, I know future me will look back at Gusto today and think, wow, they were just getting started. There’s still so much to do.” That restless, forward-looking, rarely satisfied mindset has defined London’s decade at Gusto. Even as the company scaled nationally and matured beyond its ZenPayroll roots, he struggled to see any moment as a true arrival. “That performance anxiety has been there the whole time,” he says. “It’s not doubt so much as fuel — a sense that Gusto’s success has always been a midpoint, never an endpoint.”

He can pinpoint the first time he felt the company gaining real traction — around the Series B, when Gusto hit tens of millions in annual recurring revenue. Yet he still didn’t feel it was a moment to exhale. What he remembers of that time is the emails he would sent his team. We’re not growing fast enough. Onboarding takes too long. We need more of this kind of customer.

“If you’re not on your toes and trying to disrupt yourself, to innovate and move fast, you’re going to lose,” he says. “This is not the industry to sit back and hang out and think about the past.”

Still, beneath the urgency is a principle London credits to his father’s clothing shop in Haifa — a belief that real success is measured by longevity, integrity, and a customer first mentality.

“There is something around long-term orientation that I learned from my dad,” he says. “For the customer, it's not a transaction, it's a relationship. It's about building something for the long-term in a respectful way that you feel proud of the ‘how’ later, but without sacrificing performance.”