Earlier in her career, Karen Rhorer was rising through the sales ops leadership ranks and working with her team to come up with an aggressive hiring plan, trying to reverse engineer the sales team capable of delivering the equally aggressive bookings numbers that their startup had set.

At the time, this move seemed in-line with conventional thinking, which was steeped in hypergrowth and the triple triple double double double mantra that drove startups to sell more, faster. But that pressure to hit those top-line growth numbers created blinders that left one side of the equation out entirely: sustainability. Like many other companies, Rhorer’s startup didn’t realize early enough that the math wasn’t supporting the sheer amount of cash they were burning in a quest for growth. And just a few years later, it all came home to roost — and nearly 40% of the staff had to be laid off.

Rhorer has carried the lesson from this cautionary tale forward, carefully avoiding a similar mistake in her roles that followed. With a career that’s stretched across consulting, finance and sales operations, she’s become one of the most structured and analytical sales leaders out there, able to craft growth and performance plans from big picture strategy right down to executing the very tactical details of implementation. She went on to successfully manage sales strategy and operations teams at LinkedIn as it integrated its acquisition of Lynda.com and expanded learning solutions in EMEA, and then moved into her current role as the customer success and sales strategy lead for Atrium, the latest venture from the co-founders of TalentBin.

With the experience Rhorer brings to the table, it’s worth heeding her advice, especially when it’s cautionary. Because recently, she’s noticed the same warning signs that the growth-at-all-costs sales mentality is worming its way back through Silicon Valley as venture checks balloon and more competitors emerge. In this exclusive interview, Rhorer codifies what she’s learned about scaling sales hiring across her career, hoping to help other companies avoid the mistakes that she’s seen too many startups make. She shares how leaders can push past the pressures to spin up sales quickly by walking through the four levers for sustainable headcount planning and detailing the key calculations for avoiding a painful future of upside-down metrics that burn through cash.

BEFORE POURING IN THE GAS, MAKE SURE THE ENGINE IS WORKING

It’s a tale as old as time. Founders push sales orgs for growth to hit the numbers needed for the next round of fundraising. The ask stems from a need to show product/market fit in the form of revenue. With headlines of massive rounds being raised, founders feel that if they let up on the growth pedal, their competitors won’t. The first few sales folks are hired, and instead of that releasing the pressure it increases it. All of a sudden, plans are made to double or even triple the sales team as a sort of rush-order on revenue.

But according to Rhorer, that’s exactly when you need to hit pause and crunch the numbers instead. “That kind of thinking is not going to result in sustainable, healthy startup. Frankly, it's a dangerous simplified headline that ends up being a simplified business model. It overlooks so many things,” she says. “Before you know it, you’re burning more cash than you expected while bookings are increasing more slowly than you projected and it’s a full-blown crisis. It’s like raising an army of soldiers and forgetting about all of the infrastructure that goes with it. You don’t want to put a lot of pressure on the system without actually thinking through what that looks like. Ignoring your cash burn to achieve growth in the short-term can lead to painful layoffs later on.”

A growth-at-all-costs mindset is a recipe for out of control burn and topsy-turvy unit economics.

Now at Atrium, Rhorer is pursuing a much more measured approach. “It's only now that we’ve figured out the sales motion that we’re going to hire one person outside of the founder to focus on sales. And it’s just that one hire, because we want to make sure that the sales motion is real and replicable before we hire a fleet of account executives (AEs),” she says. “You need to understand the fundamentals before pouring gas on the fire because you want to make sure it’s going into a working engine, not onto a conflagration that will burn through your VC money.”

To check the engine light and see if it’s time to scale up the sales team, founders and sales operators need a clear view into the gears that drive sustainable growth. To that end, Rhorer has developed a detailed process with four steps leaders can use to pinpoint the right time to scale sales hiring — and make sure they aren’t setting their future selves up for a costly fall.

1) LEARN THE NEW MATH: A BETTER (UNIT) ECONOMICS 101

Founders and sales leaders need to first clear the hurdle of fully understanding the unit economics of their go-to-market model, doing the math on the most basic elements. To tackle this meaty task, Rhorer breaks it down into four sub-steps and provides basic and more sophisticated approaches as guidance:

Elevate your customer acquisition cost calculation.

Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is an oft-cited metric to track, but there’s more to this calculation than meets the eye. In Rhorer’s experience, people usually miss the fully loaded cost of the sales and marketing efforts required to nab a customer. “Your sales people are not just their salary and commissions expense. There are also costs associated with benefits, management overhead and sales technology spend, in addition to everything on the marketing side. It’s important to include a G&A allocation that fully bakes in all of the true costs,” she says.

For a really basic estimate, look at the total amount of money that’s spent on sales and marketing and divide that by the number of new customers acquired in the last quarter. “Of course, if you have sales reps that are both winning new customers and renewing or upselling, I’d recommend figuring out the rough portion of time they’re spending on new customer acquisition and using that allocation to estimate the percent of total sales cost to include,” says Rhorer.

How to take it a step further: Get even more sophisticated by looking at the granular details of CAC by customer type. “If you want to go further than just analyzing your overall CAC, look at each of the customer segments you support and proportionally allocate spending. If you are selling to really unique verticals, then the cost to acquire those types of customers will be different,” says Rhorer. “For example, it may be that marketing is putting a disproportionate percentage of their resources against SMB customers because that segment is best reached at scale via marketing efforts, whereas a sales team could focus only on enterprise accounts.”

Calculate your customer lifetime value (including customer success costs).

To ensure that user acquisition is profitable, startups need to run the numbers on how much these newly acquired users will be worth. Many have touted the power of customer lifetime value (CLV) as a funnel analysis tool and Rhorer sees it as an important lever to consider before pulling the trigger on sales hiring, provided that it includes a full accounting for customer success costs.

“You’re trying to understand how much a customer will be worth during each year that they are a customer, after accounting for the cost to keep them around. People often forget this piece. They’re quick to count the revenue but then miss the spend that comes afterwards,” she says. “As a basic initial approach, take your average deal size, multiply it by your net dollar retention rate to get your year two expected value, and then keep doing that for the number of years you expect your customer to stay a customer to find the lifetime revenue. Then multiply that by your gross margin to back out the costs of supporting, retaining and upselling that customer. This can get a little complicated because what you’re functionally doing is calculating the present value of an annuity, so I've built a simple metrics calculator to help simplify this process.”

Rhorer advises relying on churn rate in the explanation above in cases where the average customer lifetime is still premature for an early-stage team.. “As a simplifying mathematical assumption, if you know what percentage of your customer base churns every year, your average customer lifetime is going to be the inverse of that. So if 25% of your customers churn every year, then your average customer lifetime is four years or 16 quarters,” she says. “In place of hard numbers, start with reasonable assumptions and continually monitor to make sure that they stay reasonable. If you’re selling to SMBs and it’s a super transactional sale with lots of competitors and low switching costs, you’re probably going to have a shorter customer lifetime than somebody who does a complex enterprise sale.”

How to take it a step further: For those ready to move beyond assumptions and wade even deeper into a CLV calculus, Rhorer shares two steps to go beyond the initial equation:

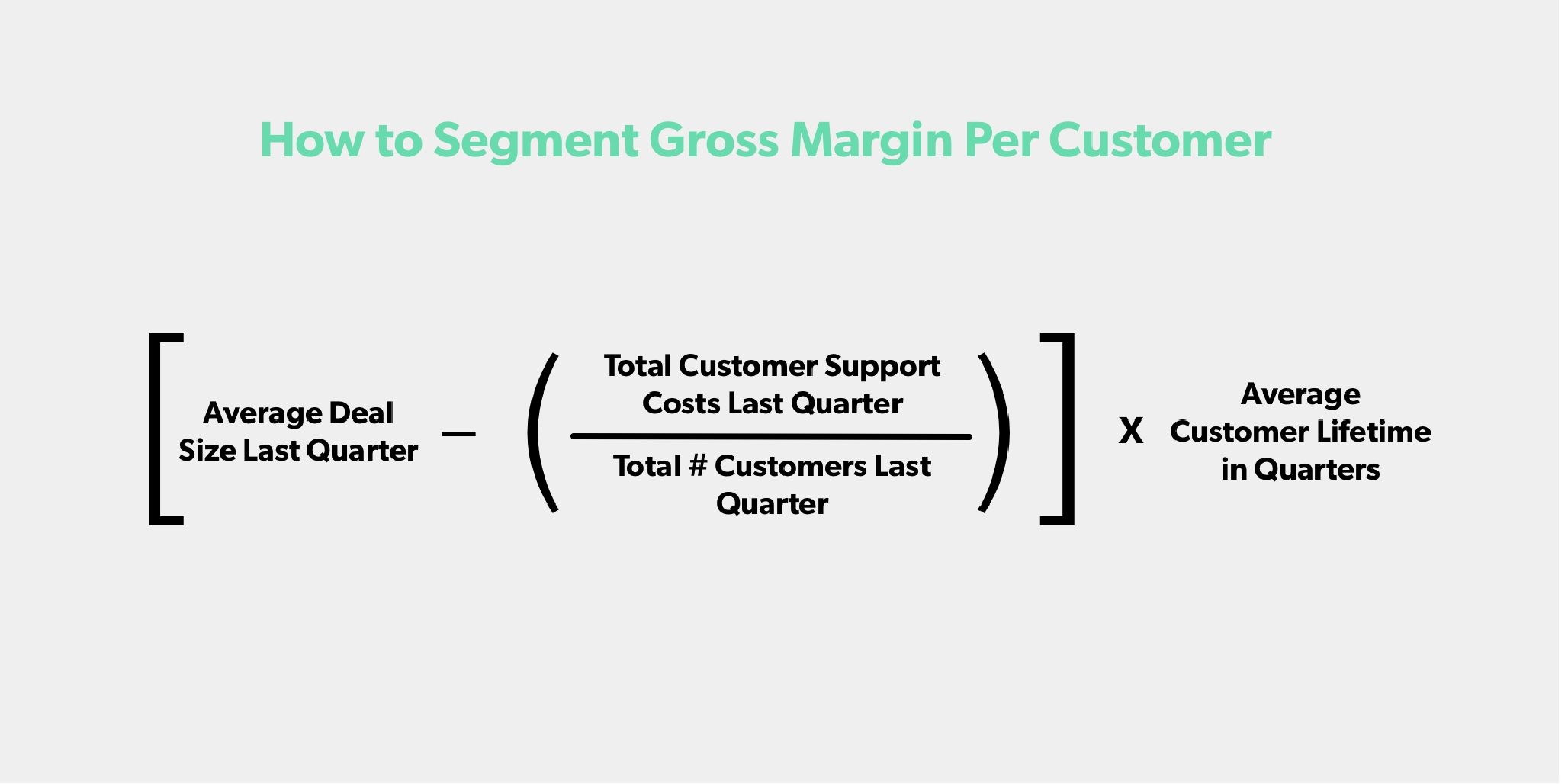

- Take a more tailored approach to costs. “Instead of using gross margin, look at the direct expenses for supporting your customers, such as AWS servers, and your fully loaded account management and customer success headcount and technology expenses,” she says. “Add these up to find your quarterly cost of goods sold (COGS), divide that by your current amount of active customers and multiply that by the number of quarters in your average customer life. You can then subtract this lifetime total cost of supporting a customer from your total bookings value per customer.”

- Break down CLV by customer segment. “When I was using the more basic approach of looking at overall CAC and CLV at my first startup, we missed that we were selling to three distinct customer segments with highly divergent economics” she says. “What we discovered was that the cost to acquire customers was different across those segments but not sufficiently different for the revenue we were generating from each. We ended up refocusing on an enterprise segment because the lifetime value was so much higher, in relation to the customer acquisition cost.”

Double-check that your ratios are reasonable.

After calculating these figures, leaders should take stock to see if they’re on the right track. When it comes to keeping LTV and CAC in line, there are two general industry rules of thumb that Rhorer follows: aim for a CLV that’s at least three times CAC and pay back CAC in less than 18 months.

“These are popular principles for a reason,” Rhorer says. “If CLV is only 1x of CAC, that means that it only covers the amount of money that you spent acquiring that customer. So by definition, your customers are not covering any of your other business expenses. That doesn't leave any money to pay your engineers to build and maintain the product that you sold them, so that's clearly not sustainable.”

The bookend on paying back CAC is similarly rooted in sustainability. “It’s possible to be a profitable business at scale and have a long payback period in a scenario where your customers are super expensive to acquire but stick around forever,” say Rhorer. “But usually a long payback period means that you’re spending a lot of cash in order to scale.”

If it’s taking a long time to pay back CAC, that should set off an alarm that the sales motion isn’t actually working.

For the startups struggling to hit these key ratios, in Rhorer’s experience, it usually comes down to a mismatch between their go-to-market motion and the customers they’re going after. “If you have an SMB inside sales motion where average sales prices (ASPs) are a little bit smaller and the renewal rate for customers isn't quite as good, it’ll be harder to make the unit economics work if you're staffing a whole team against that customer. The margins just aren’t there and you need to be realistic about that,” she says.

To help make all this number crunching easier, Rhorer has created a simple metrics calculator. Plug in your own numbers to calculate CAC and CLV, as well as confirm that the ratio and payback period are both on track.

Factor in ramp for new hires.

While it’s easy to get swept up in the trap of thinking that adding more salespeople will quickly boost growth, new hires clearly don’t walk in closing deals on day one. Every new AE will always be unprofitable in his or her first few months with the company, but Rhorer has found that many leaders fail to build that burn into their financial models.

“It’s important that you know how long it takes a new hire to consistently reach full productivity so that you can account for their cash negative time period. Their ramp is dependent on what your average sales cycle looks like,” says Rhorer. “If it’s four months, then it’s going to take a new AE at least that long to ramp.”

You aren't going to get an account executive to fully ramp productivity in two months. It's just not going to happen.

In addition to the loss of productivity that accompanies a newbie’s first few months, Rhorer sees another point that others overlook. “Many just talk about how quickly can people spin up and bring cash in the door. But I think what’s not mentioned is how ramping up AEs efficiently frees up more management bandwidth. If you have a plan to shorten AE ramp time, you’ll be able to hire your next cohort of AEs more quickly or focus on other business priorities, so speeding up the onboarding here can really increase your enterprise value.”

But the line between ramping slowly and not being a fit is razor thin — and hard to spot. Rhorer offers some tips for teams looking to make the distinction:

- For the first sales hire: While passing over the reins to a dedicated sales hire can provide a sense of relief for founders, it can also be a source of stress. New hires can struggle to find their sea legs, so it’s common for leaders to be unsure of how to gauge their performance — and wonder if they made the right call by pushing the sales work off their plate. “If you have the founder selling for long enough, when it comes time to hire that first rep, you’ll already know what success looks like,” says Rhorer. “For example, at Atrium, I know how many opportunities our co-founder Pete Kazanjy works on at a time and how long it takes him to close them. I know what his ASP is and how many meetings he's in every week. So when we have our first AE come on board, we’ll already know those rough benchmarks in the onboarding plan. And if things are falling short, I can go back a step or two to see if it’s a bad hire or if the levers are different for a co-founder and an AE.”

- For the next cohort of AEs: For the mid- to late-stage teams that have already started to build out a sales army, there are other markers to look for. “When you have a new batch of AEs, compare their ramp to that of other AEs when they were at the same tenure. Establish a general profile of a successful AE with benchmarks on the number of meetings scheduled, opportunities advanced and pipeline built,” says Rhorer. “Look at a new hire’s progress every month until the end of the full sales cycle. You should see the number of opportunities and ratio of initial meetings to follow-on meetings going up as the months go on. If everything’s as expected, then it’s all systems go — you can stay the course on the same training or coaching plan. If those things are falling short, then that's where you can step in.”

On the other end of the hiring funnel, it’s important to pay attention to attrition rate as well. “You don’t want to end up in a situation where the AEs you’re hiring are never actually paying for themselves,” says Rhorer. “You have to address training, onboarding or retention issues before adding any extra headcount; otherwise it’s a leaky bucket.” Avoid this headache by spending the time upfront making sure you have the right people in these roles. “Make sure your hires actually want to be doing this job. One sales leader I know has candidates come in for a trial day that they get paid for before they’re formally hired. There’s a decently high drop off rate after that trial day, but it’s a great way to weed out those who aren’t serious,” says Rhorer.

2) FILL IN THE GAPS IN THE HANDOFFS

For Rhorer, the transition between sales development reps (SDRs) and AEs is a particularly important part of the sales cycle that requires tight and repeatable unit economics. New AEs need a predictable pipeline volume, so it’s key to put SDR productivity — and retention — under the microscope.

“You will always have a random bluebird outlier deal happen, but if the inputs and outputs are pretty similar over time, then you can understand what will happen when you hire another SDR or AE,” says Rhorer. Here’s her checklist for assessing SDR performance before kicking things into overdrive:

- Do you know how long it takes a newly hired SDR to reach full productivity?

- Are inbound SDRs converting marketing qualified leads (MQLs) to opportunities at a consistent rate?

- Are outbound SDRs generating meetings and sales-accepted opportunities at a consistent rate?

- Do you understand how many accounts an SDR needs to touch to generate a meeting?

Once the system is firing properly, the sales cycles become predictable and SDRs are performing, the conversation quickly turns to career pathing. There’s an inherent tension here. Successful SDRs are often hungry and growth-minded — and not eager to stay in their role for longer than 12 months, despite the significant investment in their ramping period. It often seems as though as soon as success is achieved, SDRs are promoted and the cycle of ramping starts all over again on both ends.

“One thing I've seen be successful is putting in intermediate roles so that there is a promotion point within SDR. They can take on more responsibility or generate more income, but you aren’t losing that productivity,” says Rhorer. “Another strategy involves hiring a mix of those super growth minded people and people who want more predictability and are happy to stay in the SDR role for a longer period of time. It’s very similar to what many companies do with the individual contributor track versus the managerial track.”

It’s also important to have foresight when backfilling. Founders should plan a few squares ahead as people get promoted up the sales ladder. “One common pitfall I see is that SDRs perform very well and get promoted to AEs, but it’s only then that folks start thinking about backfilling those SDRs,” says Rhorer. “If you want to make sure newly promoted AEs are going to have pipelines of their own, as soon as you make the decision to promote, you need to be out there with an open SDR req trying to hire backfills. If you had two SDRs supporting five AEs and decide to promote both of them without immediately backfilling them, then whatever pipeline they were generating before goes away. It creates a gap that will need to be made up with AE self-prospecting, as you now have seven AEs without SDR support for some period.”

You’ll have a big management challenge if you only hire growth-minded SDRs. But if you hire none of those people, you won’t have an internal talent pipeline.

3) FARM TO FEED YOUR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES

Many startups take the time to understand where their pipeline is coming from today, but in Rhorer’s experience, not enough spend work out where it will come from tomorrow — and how a new legion of AEs will be fed with fresh leads.

“People think that hiring sales people automatically leads to more deals, but inbound lead volume doesn’t scale as you hire new AEs. If you currently have five AEs and 50% of each of their pipelines came via inbound channels, then hiring an additional five AEs means that you will have 10 AEs with 25% of their pipelines coming from inbound — unless you get marketing to commit to delivering more leads. It’s almost entirely independent of how many AEs you choose to hire,” she says.

To help keep new AEs satiated in the long-run, Rhorer offers two tactics:

- Break it down by source. Split out where your bookings are currently coming from. “It’s important to know what percent of total pipeline comes from marketing and inbound SDRs, outbound SDRs and the AEs themselves today so that you can plan for how those proportions might shift in advance. What those ratios actually are is going to be heavily dependent on what your go-to-market strategy is and what kind of customers you're selling to,” says Rhorer. “In the future, marketing will grow based on the investment your company makes in it, while the outbound SDR leads should scale linearly with the number of SDRs being hired.”

- Map ratios to sales cycle. When it comes to ratios between AEs and SDRs or follow-up meetings to first meetings, Rhorer advises aiming for a target that matches the sales motion. “If you have a big enterprise sales cycle, it may make sense for your SDR to AE ratio to be 1:1. If you're doing more of a mid-market sales cycle, maybe it's two AEs per SDR,” says Rhorer. “It also depends on what you’re asking SDRs to do. Some organizations just have SDRs set meetings while others continue to own the opportunity so it's much further developed before it gets passed over to an AE. When it comes to the follow-up meeting ratio, it’s more about your customer segment,” she says. “In SMB or lower mid-market sales cycles, I’ve seen it be just below or at one. So, for every initial meeting you have one or fewer follow-up meetings. For mid-market sales motions, that number gets closer to two. And then for an enterprise sales cycle, the ratio can get very high, depending on how big and complex it is.”

4) MAP OUT CARING BEFORE ACQUIRING

The final step in assessing readiness for scaling sales hiring involves looking at the part that comes after the sale.

“With your sales hat on, it’s easy to forget about how this plugs in to the other parts of your organization, but you really need to diagnose how customer retention is humming along before you decide to bring even more sales folks aboard,” says Rhorer. “Account Managers (AMs) or Customer Success Managers (CSMs) may be part of your sales organization, but even if they're not, they're certainly a key component in the renewal side of the equation that drives LTV.”

Whether it’s building a practice from scratch or assessing if current efforts are adding value, here are Rhorer’s tips for thinking about the customer success piece of the scaling sales puzzle:

For founders looking for advice on how to structure customer success:

“If you do no account management or customer success, I have seen churn rates as high as 50% a year, unless you’ve built out the product to do that renewal for you. But that’s not how most startups are doing it these days,” says Rhorer. “The structure I commonly see is an AM who works with the business decision-maker and is responsible for renewal and upsell, and a CSM who works on end-user success. I’ve also seen that be a combined role. In terms of where these roles slot in, both can fit under the sales organization, but I've also seen them roll up into a chief customer officer so that the end-to-end customer experience is owned by one person.”

Of course, bringing AMs and CSMs on board generally leads to much lower customer churn rates, but there are significant costs involved in supporting that. “That's why all the math is there. If you’ve got support costs in your LTV, you can make sure that the decision to have them is worth it,” says Rhorer.

For founders trying to evaluate current retention efforts:

“When you’re thinking about stepping up your sales hiring, you need to think through how that will impact your current customer operations. How many accounts does each of your AMs or CSMs cover? Are they at capacity?” says Rhorer.

She advises taking a particularly close look at changes in staffing or the number of accounts per manager. “If you’ve been overstaffing customer success, but know that model is financially unsustainable over the long term, you should plan for some increased churn as the customer success model moves from high-touch to low-touch,” says Rhorer. “Similarly, if the number of accounts or touches per account manager has been changing, watch for how that impacts customer health scores like product usage and NPS so that you can forecast the future impact on churn and adjust your LTV/CAC calculation accordingly. But if you feel good about how the current model is working, the only thing to do is to make sure that you hire additional AMs and CSMs to go along with the additional AEs.”

Just as you want to make sure the AEs will be “fed” before you hire them, have a plan to care for customers before you acquire them.

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

While hitting the sales-fueled growth button may seem like an appealing shortcut to the revenue numbers investors seek, founders should take the time to understand and fine-tune their sales motion before spinning up a full-blown sales team. Understand your unit economics by calculating CAC and LTV, breaking out customer segments and more tailored costs for a more advanced approach. For sustainability’s sake, make sure LTV is three times CAC and aim to pay back CAC in less than 18 months. Build ramp time for new hires into your model and set up checkpoints to evaluate their success and ensure everything’s on track. Consider creating an intermediate promotion point for hungry SDRs and hire the right mix of superstars and rockstars to keep your sales talent pipeline stable. Feed AEs by backfilling SDRs who get promoted and matching your SDR to AE ratio to your sales cycle. Finally, don’t forget about customer success’ impact on LTV. Think through how any changes will affect churn and make sure AMs and CSMs are hired in line with AEs.

“Taking these steps in advance will help ensure that you don’t make commitments that your future self will not be able to afford. It’s a lesson that everyone really needs to learn. I keep having these conversations with CEOs who are thinking about hiring because they’re being asked to hit this growth number, but there are just so many things to think through here,” says Rhorer. “You have to look at all of the other parts of the equation to see what makes growth sustainable. When it’s working, do you really understand why? Or do you know what to look at if it's not? I’ve seen firsthand what happens when you focus on growth without having answered these questions and then have to lay off members of your team as a result. Having a focus on growth is important. But having a singular focus on growth to the exclusion of other things can be incredibly perilous — and founders that are serious about sticking around for the long haul need to keep that in mind before setting off to the races.”

Photography by Bonnie Rae Mills.