As our Marketing Expert in Residence here at First Round and in her own consulting work Arielle Jackson has helped shape hundreds of startup brands. If you suspect we’re padding the tally for narrative effect, by her count she worked with 71 companies in 2021 alone — and she’s been at this work for the past seven years.

So it’s fair to say that if you’re a founder building a brand, you’d want Jackson in your corner. For the better part of the last decade, she’s helped companies like Patreon, Loom, Front, Bowery and eero architect their positioning and brands from the ground up. (To say nothing of her previous product marketing work at Google and Square, where she helped launch and grow products such as Google Books, AdWords, Gmail, and Square Stand.)

Jackson has previously tapped into this deep well of experience to crystalize and share early marketing advice for founders right here on The Review, from a popular positioning framework and set of branding exercises, to detailed guidance for technical founders looking to hire their first marketers.

Recently, she marshaled this experience into a new format, a cohort-based-course powered by Maven, that allows her to work with even more early-stage founders. In distilling lessons learned and sketching out the tentpoles of the curriculum, Jackson found herself making a list of the mistakes that she was keen to help her students avoid — one that she thought might be helpful to share with Review readers as well.

“Working with hundreds of brands has cemented the importance of focusing on the fundamentals of your purpose, positioning, and personality early on. These are the essential elements of a brand strategy. When you get this stuff right, everything flows from there. You don’t get distracted by the competition. Your website writes itself. Your messaging breaks through the noise,” she says.

In this exclusive interview, Jackson outlines seven of the most common early marketing mistakes that she sees, sharing the very exercises and frameworks that she uses to help founders launch quality brands quickly.

Whether it’s the trap of focusing too much on other startup competitors, or the tendency to emphasize emotional over functional benefits, Jackson details the brand hurdles standing in every early-stage startup’s way, offering up a guide that’s deeply tactical and laden with examples from countless companies to bring these concepts to life.

MISTAKE #1: SKIPPING THE FUNDAMENTALS AND DIVING STRAIGHT INTO THE TACTICS

In the earliest of days, a founder’s marketing efforts are often more on the slapdash side of the spectrum. A landing page gets spun up here and some copy is thrown together there, while a hasty first iteration of the company name and logo makes its debut.

But taking a step back to think through how it all fits together matters, says Jackson. “There’s a tendency to think, ‘I don’t have to worry about brand right now.’ But once you’ve worked out the basics, such as your company purpose and your product positioning, tasks like figuring out your pricing or writing copy for your homepage become easier.”

In the early days, it can feel like you’re reinventing the wheel with every piece of marketing that you have to put out into the world. But when you start by focusing on your brand fundamentals, you’ll have a guiding light that will make every decision easier.

For Jackson, that minimum viable brand strategy revolves around three elements. If you haven’t read her previous Review articles, we recommend starting there. But we’ll give a quick cliff notes overview of her recommended process here:

- Step 1: Define your company purpose. “When I work with early-stage startups, we always start with the company's purpose. Why are you here? And why should people care?” says Jackson.

- Step 2: Plot out your product positioning. “The company purpose exists on a 10-year horizon and your product positioning exists more on an 18-month horizon, roughly from pre-launch to your Series A. So first the basics: What’s the thing that's coming to market? What does it do? What category is it in? Who’s it for? Why should people care? Who are you playing up against?” she says. “Then, your differentiation — the unique points that provide reasons to believe your product’s benefits, ones that the competing alternative cannot claim.”

- Step 3: Cultivate your brand’s personality. “This is how you show up, particularly in written copy, but it also informs visual identity. It’s the feeling you get from the company. If the company were a person, what would it be like?” says Jackson. “This gets everyone writing in the same way, and delivers a consistent look and feel.”

MISTAKE #2: OVERCOMPLICATING YOUR PURPOSE

“A lot of founders come into our working sessions with a purpose statement, a vision, a company mission, a set of values, a tagline — but it’s more of a collection of catchphrases that nobody pays any attention to. They don't have that one statement that's being used both as a company decision-making tool, but also as a way to get people root for them,” says Jackson.

So many startups spend tons of time fiddling with their mission, vision and purpose statements. No one wants to remember all that — and rarely does it actually guide behavior.

Below, Jackson makes a case for why defining your company purpose is so critical, and shares ideas for how to put it to work:

What good looks like:

“There's been some backlash on purpose in recent years, with folks debating if it even matters. At a bare minimum, it’s important for rallying your internal employees — but I believe it matters for everything,” says Jackson.

It’s all well and good to have your own internal goals, but for external messaging, flip it to: What is the change you want to see in the world, irrespective of financial gain? That’s really where a good purpose lies, Jackson says.

Company purpose is about how you’re going to make a mark on the world — not how you’re going to add to your bottom line.

Here’s a few examples that have stood out to Jackson over the years:

- Square: “For a long time, Square’s purpose was ‘to make commerce easy.’ It was rooted in the company’s origin story of how co-founder Jim McKelvey lost out on a sale at his glassblowing studio because he couldn’t accept American Express.”

- Nike: “Their line is so iconic: ‘To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete* in the world. *If you have a body, you are an athlete.’”

- Stripe: “‘To increase the GDP of the internet’ is not without financial gain for them because, of course, they get a cut of every little piece of internet GDP that they produce. But it's really pointing to something much bigger — if the payment rails of the internet were better, more commerce would happen there.”

Not sure if your company purpose meets this bar? Here’s her litmus test: “Let's say you're a 10-person company, and I asked everyone, ‘Why does your company do what it does?’ I’d likely get 10 different answers. What is the purpose statement we can shift to, where in three months, if I asked all 10 people again, I would get everyone saying the same thing?” she says.

“I joined Google when there were around 1,300 people, and every single person could say, ‘Google's mission is to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.’ I recently worked with an ex-Googler who left when there were 80,000 people and he said most employees could still recite that mission, which is impressive.”

How to get there:

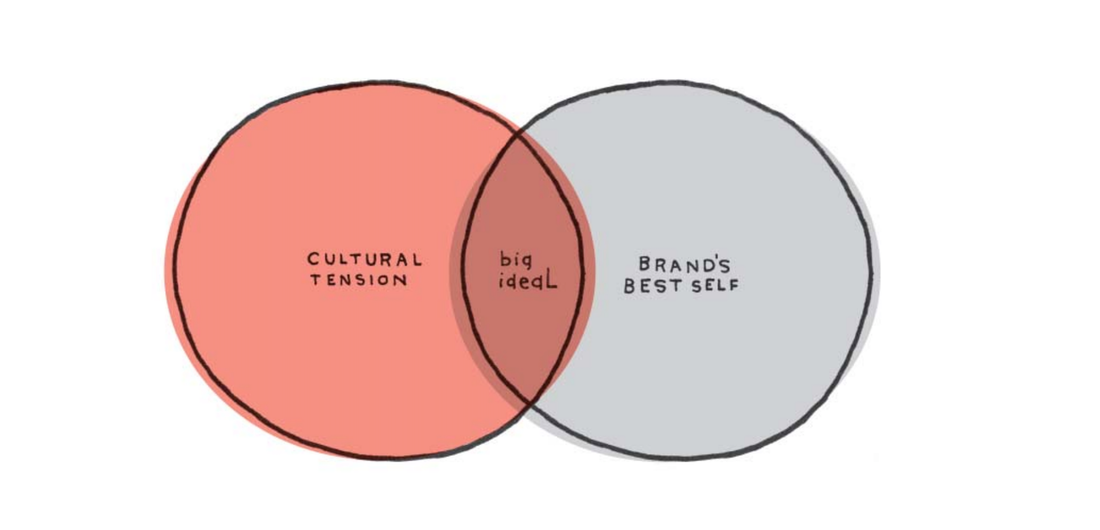

“This is a clear example of where I find frameworks are useful, because it's really hard just to be like, ‘Go brainstorm your purpose, good luck!’” says Jackson. “I go off of Ogilvy & Mather’s The big ideaL framework, where you brainstorm all the things that are happening in the world that are relevant to you as a company and your brand at its best.” (Read more about how to apply this framework in Jackson’s previous article.)

How to actually use your purpose:

Once you have a purpose that you’ve articulated well, there are plenty of places to put it to use. Here are the ones Jackson mentions to early-stage founders most frequently:

- Making decisions: “The first and foremost use case is as a North Star for decision-making. Ring’s ‘We exist to make neighborhoods safer,’ is a great example of this. I’ve heard the CEO Jamie talk about how that gave him ammo to go to his board and push back on ideas that he wasn't happy with, like raising the monthly subscription fee. It also helped make product decisions easier — what’s the right angle for the camera lens to capture to promote safety?”

- Introducing yourself. Think about the times you’ll get up in front of an audience or at a conference. What’s your opener, something that would make people want to hear what else you have to say? “It’s important that it’s consistent and inviting in this context, that's it’s an idea someone wants to root for,” says Jackson. “Irving Fain at Bowery does a great job of this. They’re an indoor vertical farm and their purpose is to grow food for a better future. Whenever he would talk to a reporter, or speak at a conference, he would introduce himself that way.”

- Recruiting and onboarding. “Same thing goes when you're reaching out to candidates with cold emails on LinkedIn — always lead with your purpose, and then explain what your product does,” says Jackson. “To get to the place where the whole company is saying the same thing, make sure that continues in internal onboarding.”

- On your website: “If you have a great purpose, you should put it in big font as the header on your ‘About’ page. If you’re hesitant to do that, or it reads really clunky, then you’re not there yet.”

If your purpose can't help you make decisions, it's not a good purpose.

MISTAKE #3: NOT CAREFULLY CONSIDERING YOUR CATEGORY

“Category definition is a part of the broader work of positioning, and it’s one of the main components that I find founders tend to trip up on,” says Jackson. “Put very simply, you need to be able to say, ‘Company X is a Y that does Z.’ Y is the category in which you’re playing — give me a mental model for what I should think about when I think about your company.”

There are two strains of mistakes that she tends to see here. “One is just not thinking about it at all. Surprisingly often, founders don't try to define which category they're playing in,” says Jackson.

Abdicating the chance to make a conscious choice can have consequences. “If you don't define the arena in your target audience’s mind, they will have to do it for you — and they'll do eight different versions of it and it won't be clear,” she says.

“I worked with Patreon at a point when users were describing the product like a tip jar, a way to throw a couple bucks at a creator who you admired or wanted to support. But when we ran through the positioning exercise, it became clear that they wanted Patreon to be a way to subscribe to a creator's content, so we shifted their category to be a membership platform for creators.”

The earlier you do the work to define who you are, the better off you’ll be. If you can’t articulate what you stand for and where you play, you won’t be able to occupy that space in your target customer's mind, much less march along to the same beat internally.

The second pitfall Jackson often sees is that when founders do consider category, they’re almost always tempted to chase the same option: creating a new one. “Play Bigger was a really popular book a few years ago, and it put out a message that the players who won defined a new category, which I think is why founders are so big on category creation now,” says Jackson. “But there are actually three different choices, so considering the alternatives and making a thoughtful decision is crucial,” she says.

Here’s the menu:

- Take on an existing category: “This can be intimidating, but it’s not always a bad choice. I worked on Gmail early on, and we decided to play in free webmail. At the time it was Yahoo! mail and Hotmail, so there were incumbents to take on. Or think about Amazon deciding to play in the retail bookseller space when they started,” says Jackson. “If you choose an existing category, you have to think about whether you could someday win that category. So with Gmail, we really thought that we could own the category by building a better version of free web mail.”

- Make a modification: “This is when you take an existing category that people have a good understanding of and tweak it. My favorite example is Nest. For years, thermostats were boring, sat on your wall and didn’t do much. And Nest had this brilliant idea to just add the word ‘learning’ to the word ‘thermostat,’ carving out a sub-segment of that category that they could own. Prose is another good consumer example, with ‘custom shampoo.’ But there are tons of B2B examples as well, like Marketo with ‘marketing automation,’ and Sprig with ‘continuous research,’” says Jackson. “This one often makes sense when the market is too big and it’s unreasonable to win outright. In the book ‘Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind’ — which is one of my favorites, even though it’s a bit dated — they reference Virginia Slims, which wasn’t going to win directly against the likes of Marlboro. But they modified it to be the first cigarette for women, and for a long time were the number one product that women purchased.”

- Create a new one: “This takes time, it's expensive. You have to say the same thing over and over and over again until people get it. Uber did this with ‘ridesharing.’ Gainsight did this really well on the B2B side with ‘customer success,’” says Jackson. “If you’re choosing to create a new category, can you really lay a claim to being first, only, or best?”

You cement your category by being very consistent in the way that you talk about your product — from your website to your customer support, to your packaging, to the interviews you give. As the CEO, it should feel boring to you.

How to choose thoughtfully:

Start by exhaustively exploring the alternatives. “Take eero. We made a list of all the existing categories in the home wifi space. They could have been a router. We could have modified it to make it a modern or a premium router. And then we looked at how we could potentially create a new category by brainstorming all of the possibilities,” says Jackson.

“One that came up was ‘home wifi system’. Enterprise wifi systems existed at the time, but they were never built for a home market. The CEO Nick latched onto that. He understood the challenges of creating a new category, and it was a big investment, but now when you go to Best Buy, there's an aisle of home wifi systems.”

If the choice isn’t intuitively leaping off the brainstorming page, research can help. “How are your customers talking about it?” she says. “If you're a B2B business, you're selling to a buyer who has budget for existing categories, so playing in an existing category or modifying one is often a smart move. Take Sprig. If they had branded themselves totally outside of the category of research, it would have been harder to get budget from the people who manage the market research budget.”

MISTAKE #4: FOCUSING ON THE WRONG FOIL

Another component of positioning is defining what you're up against — what is your target audience doing today? “The positioning worksheet I give founders has a section for them to list who else is playing in their space. 70-80% of the time, I get a list of competitors that are other startups trying to solve a similar problem for a similar audience,” says Jackson.

“But when I talk to the founders, what I tend to learn is that all of these startups are really early and nobody has any market share yet. If you press on what their audience is actually doing today, they’re not using another one of those startups — the real foil is the old way of doing things or the status quo.”

Jackson saw the power of this perspective shift firsthand in her own product marketing career. “Back in 2007-ish, we were about to launch Google Calendar. At the time, most people at Google were using Outlook or some other digital calendar — but most people in the world were using Filofaxes. And so we positioned Google Calendar against paper calendars, rather than iCal.”

She shares three more examples, this time from the First Round community:

- Ascend: “This insurance tech company recently launched, and positioned against paper checks and manual reconciliation, which is how most people pay for commercial insurance today. It's easy to make that the bad guy, as opposed to another startup who nobody even knows about yet.”

- Composer: “They’re in the fintech space, and they allow you to create a portfolio of hedge fund-like strategies. Right now, their audience is sophisticated retail investors who want to take a systematic approach to investing but are struggling with Excel and trying to learn Python to automate their trading strategies. So that’s their bad guy.”

- Mirror: “You might expect it to be another startup in the fitness space, but when they launched, they were up against just trying to push yourself on your own with at-home workouts.”

That’s not to say you should disregard your fellow upstarts. “Keep tabs on them from a competitive perspective. You want to know what they're doing and saying — but don’t build your messaging around that,” she says.

Too many founders over-index on tracking competitors who are other startups and under-index on the behavior that they're actually replacing: the old way of doing things.

MISTAKE #5: EMPHASIZING EMOTIONAL INSTEAD OF FUNCTIONAL BENEFITS IN YOUR EARLY MESSAGING

“Benefits are another core part of your product positioning. Matt Lerner wrote a great piece on language/market fit on The Review recently that captured the mistakes I see here. He talked about how everyone wants to write the next ‘Just Do It’ or ‘Think Different.’ But Nike and Apple had already built ubiquitous awareness and comprehension, so their ads were allowed to be elusive — they had earned that right over decades,” says Jackson.

“But when you're an innovative little startup, you haven't yet. You need to be really clear and functional until people understand what you do. Yet so many founders go straight to emotional benefits, skipping over the functional messaging entirely.”

The reason? “It’s incredibly boring. And it takes a lot of discipline. But you need to challenge yourself to say, ‘What is the most bare bones, functional way I could phrase this?’” she says. Here’s a handful of examples:

- “I worked with Loom and we landed on ‘Record instantly shareable videos of your screen and cam,’ which is exactly what they do.”

- “I worked with Rupa Health through First Round, whose benefit is, ‘Order, track and get results from 20 lab companies in one place.’”

- “Sometimes I nerd out with founders on the Wayback machine to pull up some examples of what companies’ functional benefits were early on. You can often look at their homepage and the benefit is the headline. Take Peloton. It literally said, ‘Join studio cycling classes from the comfort of your home.’ That was the functional message they needed to reinforce before they could stay stuff like, ‘Together, we go far.’”

To help stay focused on the functional, Jackson suggests two exercises:

Exercise #1: Find your sweet spot on the Cinderella spectrum

“In the story of Cinderella, what is the super functional thing that happened? She had a fairy godmother who turned her pumpkin into a carriage. On the emotional side, she lived happily ever after. And right in the middle — she married a prince,” says Jackson.

Run through a similar brainstorm as you’re thinking about benefits. “List all the functional, straightforward benefits you have, all the emotional benefits you have, and all the ones in between. If you’re an early-stage startup, try to stay focused more on the functional side of the ledger,” she cautions.

“But you can still strive for a little bit of emotional evocation in your headline. Uber and Lyft had something like, ‘Get a ride from your phone in minutes,’ which is functional, but also felt a bit magical at the time when it was still an entirely new behavior. With eero, we went with ‘Blanket your home in fast, reliable wifi,’ and that word choice of ‘blanket’ got at a bit of the emotional side of things, but was still functionally saying, ‘Get your home covered in good wifi.’”

Especially if you're establishing a new category, you have to make sure people understand what the hell it is you're talking about before you can move higher up Maslow's hierarchy in your messaging.

Exercise #2: Take the bar test.

“I like to do a role-playing game where we say, ‘Pretend you’re a happy customer who's using your product. You're going to get a drink with a friend who's also in that same target audience and you're going to tell them about this new product — what would you say? That conversation is usually along the lines of:

‘Hey, I've been meaning to tell you about X’ — which is the company name. ‘It's this new Y that does Z’ — meaning it's this new category that has this benefit. And the friend would likely respond by saying, ‘Tell me more.’ And you’d respond, ‘Well, before we were doing this’ — that’s your competing alternative — ‘and this new product instead does this’ — that's the differentiator.”

“If your message can't be said out loud like that, it's not done. It needs to be written in a way where people would actually have that conversation.” Jackson shares a few more targeted pointers to help you get there:

- Remove jargon “I'm allergic to words like enabling and leveraging. People don't talk like that. The more you can speak in plain English, the more likely it is that your messaging will be repeated by your audience. It’s not about the way it sounds in your head, it’s about giving your future users a way to spread your message. Otherwise you’re going to have a mismatch between the way that your users talk and how you show up in the world.”

- Picture a bored teenager. “I've worked with a number of technical companies, and there’s a trap that both technical and B2B founders fall into. They say, ‘Well, it makes sense that you don’t understand it because you're not an engineer. This messaging is good. You just don't get it.’ But Ed Zitron, our PR Expert in Residence at First Round, uses a great line when we’re prepping founders for press — explain it to me like I’m a bored, but smart teenager. Because if they can't understand what you do, you haven't explained it well enough yet. You can’t rely on the jargon of the industry. Kubecost was an example of this. It took me a little while to understand Kubernetes, but we got there.”

- Poke the problem. “Don’t dive straight into feature, feature, feature, before telling the broader story of the problem. Even for technical products, start by asking: What's the problem and how does your audience address this problem today?” says Jackson. “And in some cases it's a problem they may not even realize they have, so you have to remind them of the problem. You’ve likely heard the ‘Are you an Advil or a vitamin?’ framing, but often products are somewhere in between — it’s an inconvenience, but something that’s easy to forget about. eero did this really well by reminding us how we had learned to live with our wifi cutting in and out, visually showing some of the crazy things people did as workarounds.”

Yes, you need some level of language that is deeper and speaks to experts in your target audience. But your first order of messaging of who you are and what you do has to be at a level where a smart, but bored teenager could get it — and that means you need to ditch the jargon.

MISTAKE #6: FORGETTING TO GIVE YOUR BRAND PERSONALITY

“Oftentimes I work with founders who have either a placeholder identity or have already invested in one. But when I ask to see the style guide, usually they send over one of those PDFs that has their logo, fonts and colors, maybe their illustration or photography style. It almost never includes, ‘This is how we show up in written copy. This is who we are. If we were a person, this is how we’d speak,’” says Jackson.

“They gloss over the personality and voice of the company, in favor of typography and color palettes. But the best style guides cover not only the visual direction of the identity, but also the tone and voice of the brand as well.”

To help founders sharpen their sense of the company’s personality, Jackson of course has a few go-to frameworks (like the voice guide she shared previously on The Review). But here’s the exercise she’s been running founders through lately: “We talk about the five dimensions of brand personality, which is academic work from Jennifer Aacker. She analyzed big brands and showed that they come down to five dimensions: sincerity, competence, ruggedness, sophistication, and excitement. Strong brands spike in two of those five areas,” Jackson says. “Take Harley Davidson, they are rugged and exciting. Or Rolex: competent and sophisticated.”

She starts by asking founders: Which areas of those dimensions does your brand spike in? “Many startups predictably choose sincerity and competence, which is the same territory as big brands like Volvo, but also tech giants like Google and Amazon.”

The next step is to figure out, if those are the two areas you need to embody, what would your five specific personality attributes be if your brand was a person? “We brainstorm a ton of possibilities, and then we pick the five that are the hardest working and the most different from each other. And, critically, we try to make sure that those have tension between them,” she says.

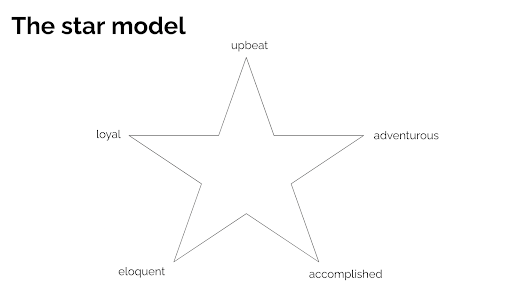

Here’s what Jackson means: “If you tell me that you're approachable, helpful, kind, diligent and nice, you've basically told me the same thing five times. But if you tell me that you’re upbeat, loyal, adventurous, eloquent, and accomplished, those five each help develop the picture I have of you,” she says.

Think about these five brand personality attributes as the five points of a star, where the top of the star is the attribute that you’d want to own if you only had one adjective. “Try to get each adjective on opposite sides of the star to have some tension between them,” Jackson advises. “For example, someone who is ‘savvy’ or ‘expert’ is not usually someone you’d also think of as being ‘approachable’ or ‘straightforward.’ Or in the diagram below, someone who is ‘eloquent’ isn’t necessarily someone you’d also think about being ‘adventurous.’”

Some examples from the startup realm:

- “When we worked on the Woolf brand, we wanted their personality and visual identity to be both traditional and modern, as they have one foot in traditional higher education and another in its future.”

- “As another example, I didn’t work with the founder, but Lemon.io has a unique brand among outsourced dev shops. In a category where almost everything looks the same, their personality and visual identity stands out. They seem to spike in sincerity and excitement, and their attributes are along the lines of straightforward, irreverent, helpful, funny, and responsive.”

MISTAKE #7: NOT PUTTING IN THE PREP WORK FOR PRESS

The work that ties your brand fundamentals together is the big moment where it’s all revealed — the fabled launch day. But given the changes in the media landscape in recent years, there’s plenty of ways for this startup milestone to go sideways.

Here are the early PR pitfalls Jackson most often sees:

- Time crunch: “A common mistake here is not leaving enough time to do it right, like when a founder emails me and says, ‘We’re launching in three days, which reporters should we talk to?’ That's just not going to happen, especially in today's world,” says Jackson. “If someone says, ‘We're launching on X day,’ my first question is always, ‘Why? What's driving that date?’ If you have your positioning down already and you truly already know how to talk about your company, you can get this done a lot faster, but if you don't have that done, rushing it is a recipe for disaster.”

- Dreaming a little too big. “So many founders have unrealistic expectations about who will want to cover them. I hear ‘We want to be in The Wall Street Journal,’ or ‘I want five big articles out of this’ pretty regularly,” she says. “Bigger publications are more interested in trends and FAANG companies than your little startup, all cool as it may be,” says Jackson. “Seven years ago, we could take a $4M seed round, go to five outlets with an embargo, and get at least three to file a story. In the current climate, we almost always have to run it as an exclusive, and there are only a few tech and business outlets that are interested in covering companies of that size and phase.” To right-size your ambitions, ask yourself: What is a realistic set of reporters who might be interested in writing about this? “People who cover education are interested in an exciting new take on the future of accreditation, but you can't expect that some random person who just generally covers tech at The New York Times will be,” she says.

- Not thinking about the content. “It still surprises me how often founders are unsure of what the story they want written even is. What is the headline you want to see? What is the news that you are sharing? That could be a funding announcement,a product launch, momentum with customers, new partnerships, anything that makes what you're doing newsworthy.”

- Unclear goals. “An offshoot of that is figuring out what exactly you’re trying to generate out of this news cycle. Even if you do secure coverage, it doesn't always move the needle in a way that is meaningful, especially in terms of usage or top of funnel awareness,” says Jackson. “What that article will do is oftentimes attract partner interest, build investor interest, or help you stand out in terms of recruiting. Another reasonable goal is getting a legitimizing link that you can share in your outbound sales.”

In Jackson’s experience, here’s how seed-stage companies succeed in nabbing that initial coverage. “One way is to build off of an existing relationship with a reporter in your space. If you're an ed tech founder, I hope you're reading what TechCrunch’s Natasha Mascarenhas is writing, because she writes most, if not all, of the edtech stories for them, so you should already be reading and talking to her. Can you be a source for a different story that she's writing? Have background conversations with her so that you build a relationship, and can tell her more about your company when the time is right?”

Another option is the “DIY approach.” “This is where you don’t hire a PR firm, and go it alone or lean on your investors to get warm introductions to the right reporter. The level of support you get varies from firm to firm. But one mistake I see here is that a lot of founders simply say, ‘Hey, we'd love a warm introduction to a reporter,’” says Jackson. “That request to your investor is so much better when you can instead say, ‘Hey, we noticed this reporter is covering our space and we think it's relevant. Here's what we're going to want to talk to them about, and here's a note you can forward to them.’”

Jackson also advises founders to think beyond their first media hit. “When you’re launching, it’s easy to just focus on that one launch announcement. But especially in today’s climate, you need to ask, what else are we going to do to achieve our goals?”

Securing your first media article is your starting line, not your finish line.

“For example, if you’re a fintech company with a consumer product, are you going to all the subreddits and posting, doing more of the grassroots style awareness building? Are you going on the podcasts that your audience listens to, not just for ads but as a guest? Do you have a paid marketing budget?” says Jackson.

“If your goal is awareness, getting one article in one outlet isn't going to be enough. Building a startup brand requires an aggregate of action that's consistent over time. After all, your brand is much more than your logo — it’s who people think you are.”

This article is a lightly-edited summary of Arielle Jackson's appearance on our new podcast, "In Depth." If you haven't listened to our show yet, be sure to check it out here.

Cover image by Getty Images/ cagkansayin.