There are plenty of reasons a startup fails — lack of product-market fit, co-founder strife, poor management skills, the list goes on. But growth expert Matt Lerner (a former PayPal B2B growth lead and co-founder of SYSTM, an online accelerator for startups that need to unlock growth) suggests something less obvious: “Nearly always, a startup's failure has to do with the founder's approach to growth,” he says.

Through his experience working with hundreds of startup founders, first as a VC and now as an advisor, Lerner has become an authority on “founder-led growth.”

It’s a concept we’re seeing gain traction, recently referenced in a write-up from founding member of Superhuman and growth advisor Gaurav Vohra, that makes the case for having someone on the founding team who specifically owns growth.

While it’s common for founders to sit in on early sales calls and spearhead product development, Lerner has observed they seldom bring this same hands-on approach to growth channels. Many are even tempted to make an early growth hire to get this off their already full plates. “Ultimately, founders need to be the ones that figure out how their business is going to grow,” he says.

Founders can't afford to delegate growth right away, nor do the best founders have to. It's in great founders’ DNA to get stuck in something and make a mess of it until they figure out what drives their business forward.

This theme is central to all of Lerner’s work, from his widely-referenced Review guide on language-market fit (a cornerstone resource for founders conducting their first customer discovery interviews) to his latest book, “Growth Levers and How to Find Them,” which transforms these insights into practical frameworks for ambitious founding teams.

So Lerner returns to The Review with another comprehensive guide, this time, answering one of the top questions founders ask him: “How do I start executing growth myself?” What follows is a playbook for founder-led growth, where Lerner unpacks the most tactical insights he's collected from working with hundreds of startup founders.

To start, Lerner shares the three common traps founders fall into that slow down their learning and sabotage their startup’s growth potential. Then, he zooms in on his signature “growth levers” framework, providing real-world examples that founders have used to drastically improve conversion rates with small tweaks. He then unpacks his founder-led growth toolbox, with clear instructions for founders to use when they're stuck. Finally, he gives strategic advice on how to imbue an experimental spirit and growth mindset into your whole team.

Whether you're an early-stage founder grappling with growth or a later-stage founder looking to get closer to the details, this guide serves as your roadmap.

Don't let these be the reasons you wait on growth

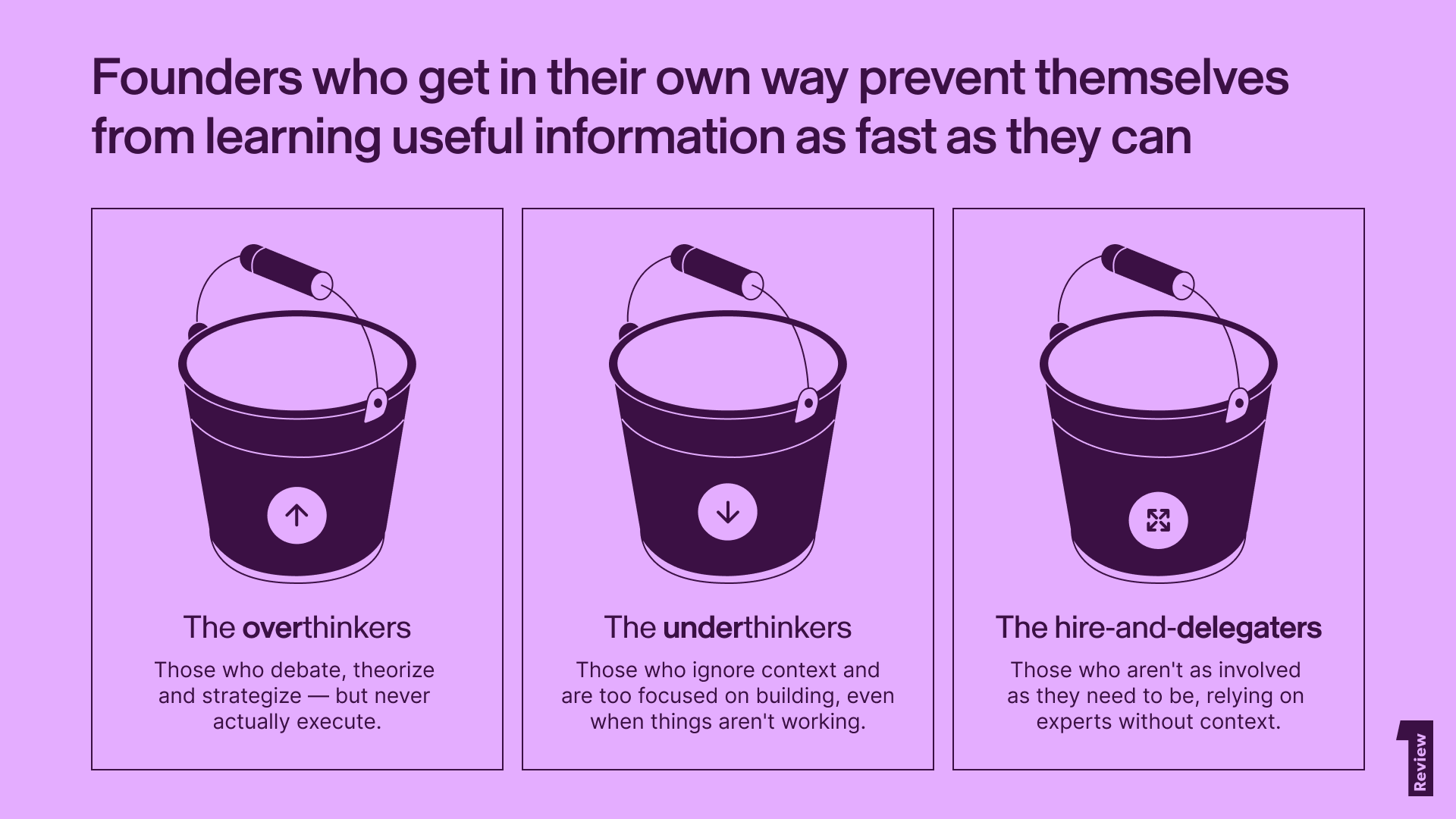

When writing “Growth Levers and How to Find Them” Lerner’s editor posed a question he couldn’t immediately answer. “One day, he asked me to explain the big reasons a startup fails in language simple enough that a 12-year-old could understand.” The answer seemed straightforward on the surface, with obvious issues like lack of product-market fit and poor management skills. But as Lerner thought more about it, he looked back at lessons from his own career and found that often, a startup fails because a founder gets in their own way of learning useful information as fast as they can. These founders often fall into three buckets:

- The overthinkers: “Founders who debate, theorize, strategize and talk to other smart people all day long and think things through, but never execute,” Lerner says. “I don’t need to tell you how that story ends.”

- The underthinkers: “These founders’ philosophy is to build, build, build, and fair enough.” he says. “But if you’re just building off your sense of the market, and your product isn’t working, adding more features that your customers don’t need, founders are just adding complexity to the product, the code base and maintenance — and slowing themselves down.”

- The hire-and-delegaters: These are founders who come from a senior role inside a big company, or who are humble enough that they rely on hiring experts for leading all the different functions. “But those outside experts don't have the right context,” he says. “They're thinking in terms of their own function, not the entire company. The founder needs to be involved in growth at the early stage.”

Lerner can see strengths in each one of these approaches — once a company is at scale. “A big business needs all three of these people,” Lerner says. “It needs smart, forward-thinking strategic thinkers, it needs executors, and it needs people who can hire brilliant people and delegate. But what a startup needs to do first and foremost is be humble and open and curious to experiment and learn.”

Strategizing, hiring and delegating are great ways to execute, but they are very slow ways to learn.

In the 0 to 1 stage, it’s easy to look at all these elements of growth — the lists of ideas, case studies, frameworks, and best practices — and feel overwhelmed. That’s where Lerner urges founders to consider this: If it works, how big can it be?

“Don’t let effort be a factor in your prioritization. I’ve said that all of PayPal’s growth came from five things, but they did way more than that. They built products nobody ever used and spent hundreds of millions of dollars on ads that didn’t move the needle,” Lerner says. “Again, often the big levers are uncomfortable, but think less of the effort and more on the opportunity cost. They’re seldom obvious, but you can find them with a process.”

The three-step process for finding your growth lever

Lerner works with founders to uncover their “growth levers”: the highest-leverage tactics for growing their businesses. “The 10% of work that's going to bring 90% of the results as quickly as possible, before you run out of money,” he says.

You’re starting with this tiny amount of resources and time and you need to have a big impact, which means you’ve got to find something that works like crazy.

Lerner first got the idea of growth levers as an investor. “As a VC, you get pitched hundreds of times and are looking at dozens of decks every day,” Lerner says. “Since my background was in growth, I focused on the go-to-market slides of each pitch. But it was also clear that many of these companies’ strategies weren’t going to work. They weren’t so much strategies as theories and lists. And if any of them did work, the impact they’d have on the business would be small.”

Watching founders focus on fruitless growth tactics made Lerner reflect on his role at PayPal, where he observed that the majority of the company’s massive growth could be traced to a handful of key bets like:

- Getting eBay sellers to use the product and turning that into a network effects loop.

- Keying in on dev relations, since developers were the ones building checkout flows for e-commerce businesses.

- Partnering with the hosts of e-commerce platforms like the predecessors to Shopify, because of course all of these platforms needed payments.

This was an important realization for Lerner, calling this power law principle “growth levers.” And eventually, Lerner developed a process for how founders can systematically find these growth levers on their own.

Lerner will only work with a startup that has a live product and some happy customers — to figure out exactly who they are and how to get more of them. Founders then often engage Lerner at a pivotal time in their company’s life where they can shift their focus toward growth. “Once a startup has some happy customers, but isn’t growing, there’s an instinct for some product people to add more features that customers want,” Lerner says. “The mentality is ‘If we add enough features, maybe then we’ll grow.’ Usually that’s not the problem. The problem at that point is go-to-market.”

These are Lerner’s simplified steps for finding your growth levers:

- Step 1: Map the customer journey. Use data to find the bottlenecks where customers are dropping off.

- Step 2: Dive into customer motivations. Interview your customers to understand what’s driving (or stalling) action using Jobs to be Done.

- Step 3: Run rapid experiments. Pinpoint a specific “lever” you want to test, designed to tackle these bottlenecks and optimize growth, and run those tests.

The goal of running through the growth process is to identify a growth lever. But that oversimplifies things. Let’s break down each of these steps in more detail.

Step 1: Mapping the customer journey

Lerner shares an example of a UK-based company called Popsa, which he invested in during his time as VC. Founded by serial builders, the app lets people make photobooks using pictures on their phones — they found a wedge in a crowded direct-to-consumer market to do this quickly and easily.

“It was clear to us that this was a product people liked,” Lerner says. “They were ranked number one in the UK App Store for photobooks, had good engagement, good retention and good repeat rates. Despite this, their view-to-install rate was low.”

Since Popsa had such a high ranking in the App Store, this was many people’s first touchpoint with the brand. “That’s where we started,” Lerner says. “Very few variables go into an App Store listing, just five or six words and a screenshot. So we looked to their tag line, which at the time was ‘Fast, Easy Photo Books.’”

Through user testing, they eventually learned that one person thought “fast” meant two hours. But Popsa could do it in five minutes. So Lerner says, “They tweaked their tagline to ‘Photo Books in Five Minutes,’ and with that one small adjustment, quadrupled their install conversion rate overnight.”

The payoff was massive. “They were already ranking number one in the App Store for their category, so with this change they were off to the races. Now, it made sense to put ad spend behind it and keep the funnel up,” Lerner says. “The company recently passed $45M in annual revenue.”

Finding this growth lever resulted from the process:

- Identify the bottleneck: app store listing page.

- Understand the customer: a misconception about the meaning of “easy.”

- Experiment: test different words to convey the value.

Now, let’s return to step one, how do you find your bottleneck?

Identify your North Star metric

“There are lots of ways to generate revenue, most of them will not lead to a billion dollar business,” Lerner says. “But when you’re a startup, you first have to be better than everyone else at delivering value to customers, at getting lots of customers, delighting them and retaining them. If you can do that, monetization is usually straightforward.”

So you want to find a North Star metric that measures the value delivered to your customers. This can be weekly actives, daily actives, or in Popsa’s case, the number of photo books made or number of memories solidified.

Pinpoint your key drivers

Once you have this North Star metric, work backwards to find what point in the customer journey leads you to achieving it. “You may have different traffic sources, but ultimately, you’re looking at each behavior point where a customer has to make some kind of decision,” Lerner says.

In other words start by asking questions like:

- How many people who view a blog post are subscribing to a newsletter?

- How many people who read the newsletter are doing a free trial?

- How many people who start a free trial are doing more than five actions in the product?

- How many people who do more than five actions in the product end up paying?

An influential factor here is the channel through which a customer discovers your product. For instance, a customer's journey would look very different if they saw an advertisement for your product on the subway versus searching for a solution in the App Store. It's important to recognize that even as an early-stage startup, you're likely to have more than one growth channel.

Once you have this funnel mapped out, Lerner has his teams do a quick pencil sketch putting numbers to these.

“Teams love to get deep into the analytics, and it’s tempting to debate these numbers, differences, definitions, and attributions for months. But at this level, founders only need to have a rough idea of the stats that line up closest to their North Star metrics,” he says. “Map that journey at a high level, and you can then go through and start to find your bottlenecks.”

Uncover your bottlenecks

While growth is often perceived as an all-out push, Lerner's model focuses on identifying and removing specific obstacles. To illustrate this approach, he draws on an unexpected source of inspiration: his experience working at an oil refinery.

“It's a great marketplace business because you get paid at both ends: First by taking dirty used oil, then again by refining and selling it again as clean fuel oil.” Lerner says. “But the rub on a refinery is that all your revenue is delineated in gallons. Your costs are all delineated in hours, salaries, leases, etc. So the more gallons you can refine per hour, the more money you make.”

But it was at this refinery where Lerner first learned the theory of constraints. “At any given time, there's the narrowest point in the throughput,” he says. “It might be how quickly we're unloading trucks of dirty oil. It might be the number of centrifuges that are working or the number of filters clogged. It doesn’t matter. What does matter is finding that bottleneck and addressing that.”

If you apply resources to a bottleneck, it makes the whole system run faster. If you apply resources anywhere else, it's wasteful and inefficient.

The same logic can be applied to startups. Unlike an oil refinery with its clear input-output model, startups rarely have such straightforward operations. But by closely examining the constraints at each stage of their funnel, founders can gain valuable insights. This granular approach allows them to measure progress against their North Star metric.

Don’t be discouraged if the bottleneck you found doesn’t end up surfacing your big growth lever. It’s all part of the journey. “Often what you think of as the bottlenecks at first don't end up being it. It’s a complex system. But at least if you start working on them and then watch how everything else in the system moves, you’ll discover the next layer deeper, one that’s closer to the root cause.”

For example, Lerner once worked with a D2C subscription company that had poor second-order retention. They tweaked everything they could about the first order experience, and nothing worked. Eventually they realized all the churn was coming from affiliate-sourced traffic, and their referrals and Meta ad subscribers had good retention rates. “They fixed retention by shifting their affiliate budgets over to Meta — what looked like a churn issue was actually down to traffic quality,” he says.

Step 2: Understand your customer

Mapping the customer journey is the behavioral side of the equation but that data won’t tell you why people are dropping off. “That’s why the other side is the mindset funnel,” Lerner says. “What’s in customers’ heads at each stage of this journey? You really need to know that before you can fix it.”

To illustrate this point further, Lerner crafts another scenario. “Let’s say you've mapped out your customer journey and discovered that people aren't converting from a blog post you wrote,” he says. “One quick solution might be to slightly animate the sign-up button on the blog's landing page, as you've read that can drive more clicks. However, what's far more valuable is understanding why your customers aren't clicking that button in the first place.”

In this step, Lerner shares tactics for both conducting quality customer interviews and how to use those insights in experiments.

Conducting interviews to uncover your customer’s mindset

“Over time, my focus has moved away from the metric side of growth experiments and more towards what's in customers' minds at any given stage,” Lerner says. “Because the metrics, I realize, just don't tell you very much. People are coming to the page and not signing up. You have no idea why. Are they not qualified? Are they confused? It’s important to move towards those answers.”

Customer interviews are a skill to be developed, like a sales call or a recruiting pitch. Lerner leans on the Jobs to Be Done framework (JTBD) here, a classic product interviewing technique, but he’s also amassed quite a few questions that can illuminate what’s going on between a customer’s ears.

Questions to peel back the layers of a customer’s goal:

- Tell me in your own words, what did you buy? "Obviously, this one is a little weird because it's your own company, and you just sold them a product. But it anchors people on the purchase."

- What would that enable you to achieve? "This immediately takes the conversation away from your product, which is what you want," Lerner says. After this, don't talk about your product in the rest of the interview until you get to their goal. "It could be a simple, functional goal such as 'I need to move all my data into one place and stop using spreadsheets.'"

With that last question, Lerner found it's best to prod even more, because there’s usually more to the story:

- Why is this goal important to you?

- Who else cares about this outcome?

Once you have a solid idea of what exactly your customer is trying to accomplish, now it’s time to dig into the specifics of how they would get there.

Questions for to map motivations to different parts of the customer journey:

- Do you remember the first time you started trying to do X?

- Where did you look?

- Where were the specific steps you took to find a solution for X?

Lerner is listening for a few things throughout these conversations:

- What do they think they’re looking for?

- Where did they look?

- Who did they ask?

- How did their conception of their project or goal change over time?

- What criteria were they applying?

- What other options did they consider? How did the other options they considered come up short, and how would you position against them?

- What anxieties or worries or questions did they have in this process?

A lot of this exercise is aimed at finding the ways your company and product can establish trust as a customer considers purchasing it. “You have to understand what specific worries and questions your customer is going to have, and address those at the points in the journey where they turn up,” Lerner says.

By following this approach, founders can uncover valuable insights that inform their growth strategy. “You do this five times, and you’ll start to see patterns,” he says. “That’s when you start to get ideas about what to experiment with.”

Step 3: Running rapid experiments

Growth sprints apply a concept from Agile software development to a single outcome: learning. Come up with a hypothesis, test it, and learn as fast as possible. Lerner even says that growth sprints operate on a tighter, more responsive cycle than Agile. “It’s more Agile than Agile,” he says. “Growth sprints typically take one week, maybe two.”

Unlike product sprints, most growth experiments fail — so learning from them is important, especially in the fast-paced world of early startups searching for their growth levers. These growth sprints give founders a framework for quickly finding what’s most impactful for their companies.

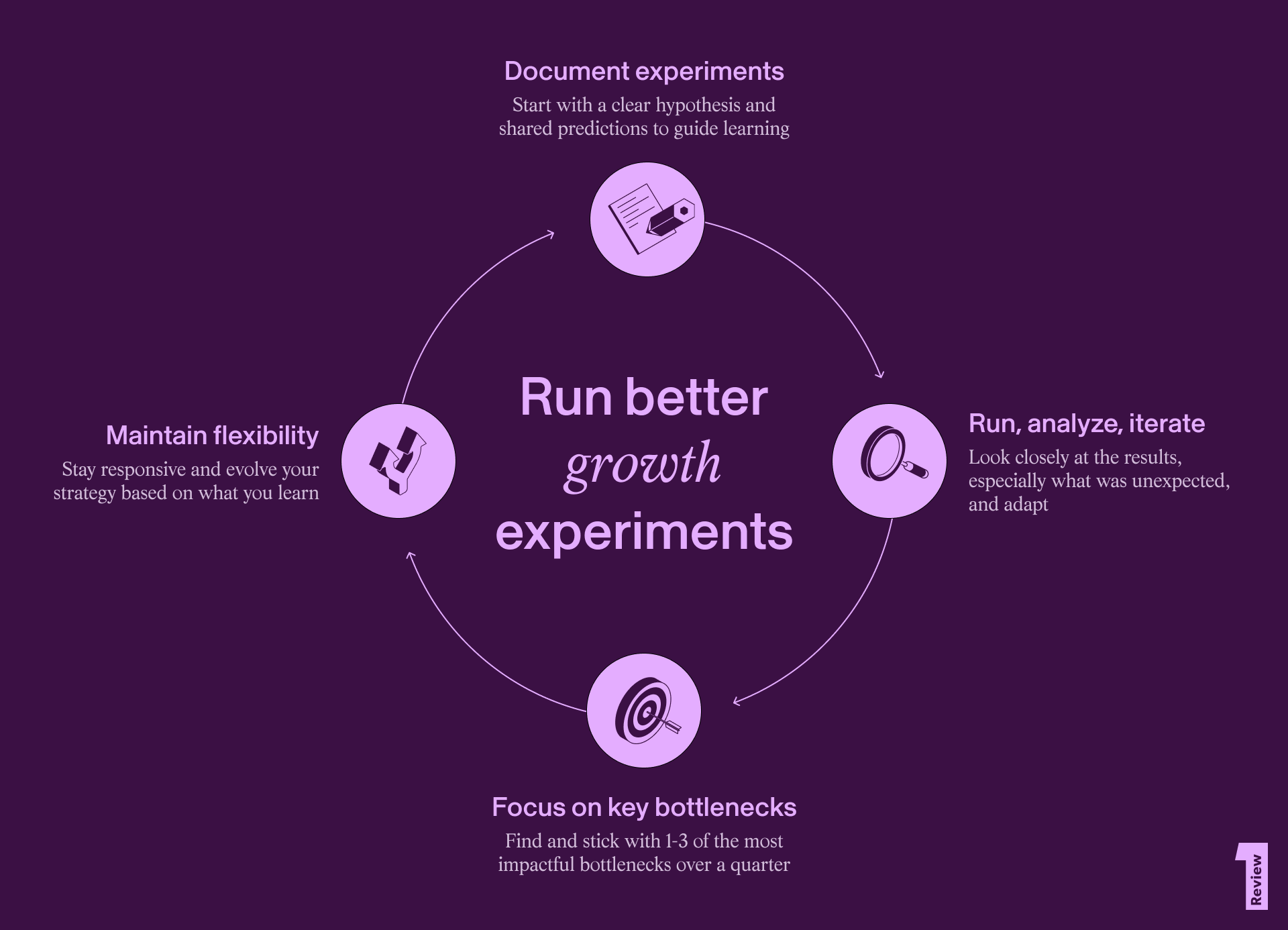

To make them more regimented and meaningful, Lerner suggests the following structure:

- Document your experiments — For each growth idea, Lerner recommends creating an experiment document. "It starts with an observation and hypothesis. Then have everyone make a prediction. Doing this in groups helps eliminate hindsight bias," he says. This collaborative approach also ensures that the team learns together, regardless of the experiment's outcome.

- Run, analyze and iterate — After running the experiment, thorough analysis is crucial. "Come back, look at the results, figure out why whatever surprising or weird thing happened."

- Focus on key bottlenecks — "At any given time, you'll be focused on one or two or three bottlenecks," Lerner says. This focused approach allows teams to direct their efforts where they can have the most impact. But more than that, it's about structuring your efforts over time. "So founders can say, 'For this quarter, we're going to focus on this and this.' Then you're going to go to your backlog and figure out the ideas that can have the biggest impact. Maybe you tried that and it didn't work, but we learned this thing, and therefore, now we are going to try another one." This ensures you're not running experiments randomly, but strategically addressing your most pressing growth challenges.

- Maintain flexibility — Perhaps most importantly, Lerner advocates for a highly responsive approach. "You're really steering the ship week by week based on your learnings," he says. This flexibility allows teams to quickly pivot based on new insights, ensuring that growth efforts remain relevant and effective.

Growth sprints have short timelines to encourage founder engagement in the growth process. The sprint also helps avoid confirmation bias. By making speed a habit, founders have a better chance to keep the integrity of their experiments intact, according to Lerner.

Here are a few more real-life examples of rapid growth sprints:

- Popsa, the digital photobook app, suspected their landing page design was too cluttered. They tested comprehension by showing customers the page for five seconds, then asking for their interpretation. Finding that customers understood it, they immediately moved to the next prepared test, focusing on audience appeal. When that yielded no results, they shifted to targeting different audience segments. This rapid experimentation continues, with Popsa running up to 10 growth experiments weekly.

- Sonic Jobs, an hourly service job marketplace, had high sign-ups but low job applications. Their welcome email used generic language like “Click here to find jobs.” Analysis showed users searched for specific roles, not broad categories. The founders updated the email with 15 links to specific jobs like “Amazon driver” or “Warehouse operative.” This simple change doubled their activation rate, significantly boosting the platform's performance.

- Smart Tales, an educational app for children, struggled with paywall conversion despite good installation rates. Through customer interviews, they discovered parents' core desire: giving their kids an iPad without guilt. It became clear the app's marketing didn't effectively communicate this value. So the founders revamped their ads, App Store listing, and pre-paywall content to address this need and alleviate parents' concerns. Without changing the paywall itself, these adjustments led to a 65% increase in conversion rates.

With each growth experiment, it’s just like you’re debugging your code. You want to break it into pieces and isolate each variable.

Lerner points out that on paper, these experiments look fairly simplistic, but each one can take several weeks at a time to get to even one answer. “Start where you think the problem is, and with efficient growth sprint hygiene, you’ll end up finding your growth levers eventually,” he says.

If you’re stuck, identify shared outcomes among your customers

If you’ve run many tests and aren’t seeing results, you can go back into customer interviews — specifically looking for the outcomes these customers hope to achieve by purchasing your product.

Lerner often notices founders go after people who didn’t buy the product in an attempt to identify where the funnel broke, which logically makes sense. But he cautions against this temptation: “There are a lot of reasons why someone might not have bought your product, but the common theme will be that it wasn't right for them in some way,” he says. “If you interview them, everything you learn might lead you in the wrong direction.”

If you don’t have customer interviews to fall back on, that’s a sign to do more of them. “You can even recruit people who just signed-up for your product,” Lerner says. “The purchase journey will still be fresh in their minds.”

Whether this user research is old or new, finding experiments is a process of pattern-matching why customers chose your product. But how you do that might look different depending on how many outcomes your product offers.

If your startup offers a single outcome, you can scan customer surveys for these patterns. “If you’re lucky, you’ll find that your best customers all have a single goal that they have in common,” Lerner says. “It could be a shared thing all customers hate doing, like asking people for a copy of their passport. Or maybe it’s a shared outcome, like all customer segments agree that the goal is to remotely verify and onboard employees and clients in minutes. You can craft your entire conversation with them around this.”

For startups that solve multiple outcomes, have customers self-select their goals. “Calm, the meditation app does this well,” Lerner says. “If you go to their site, you’ll get a screen that asks you ‘What brings you to Calm?’ It’s a multiple choice survey with options like: I want to sleep better, reduce my anxiety, improve my focus and performance at work, etc. People can then go in and self-select their outcome, making your research process that much easier.”

Once you have this data, the goal then becomes identifying and focusing on an outcome that brings in customers who might convert the easiest — they know their pain point, they have the budget and are willing to pay.

Remember: Your growth levers won’t always be novel

Don’t cringe if you’re employing the same tactics as everybody else. Perhaps the best kept secret is knowing that growth levers are not always novel, and using that to your advantage. Here are two tricks Lerner has up his sleeve when you find yourself with an inspirational block:

- Study a company who has solved an analogous problem — “For example, if you’ve got multiple use case customers or heterogeneous customer segments, Calm solved that really well with their onboarding flow. They have multiple choice questions they offer first-time visitors of the website/app asking them what they are trying to achieve. I’ve now seen B2B SaaS companies succeed with that same approach.”

- Look outside your industry all together — “Look at someone who’s in an industry that’s way further along than yours that’s nailed an analogous problem. A lot of these businesses end up combining a couple of things together. Content and inbound for example, which leads to a network effects flywheel.”

But even if growth levers feel similar at a high-level, copying and pasting shouldn’t be done mindlessly. “As soon as you get more specific than running an ad playbook, or an influencer marketing playbook, that’s where you have to get creative,” Lerner says

Tactics for getting the whole team into a growth mindset

Finding your startup’s growth levers is only 5% of the battle. “The other 95% of founder-led growth is figuring out what needs to happen at each stage of your company’s life,” Lerner says. While a founder should continue to stay intimately connected to growth levers as their company scales, it’s important to make a growth mindset part of the fabric of their startup.

Here, Lerner shares a handful of tactics that are uniquely at the founder’s disposal to cultivate a growth mindset in their org.

Overcome the “strain of mental resistance”

Lerner finds that when it comes to growth levers, founders often already have the right answer in their backlog somewhere, but resist implementing it. This "strain of mental resistance" manifests in various ways. Lerner identifies two common forms:

- Fear of simplicity: Lerner recalls working with a founder who sells software to architects in Germany. Two years after developing a proposition through customer interviews, the founder reported their best month ever in July. Surprised, Lerner asked why it took two years to test the message. The founder replied, “Well, it seemed too simple. We had all these other ideas. It just didn't seem like the right thing at the time.” It wasn't until they began rapid testing that they finally got around to trying it.

- Fear of effort: Lerner worked with Fatmap, an app with high-def 3D terrain maps for outdoor enthusiasts. Customer interviews revealed their bottleneck was qualified top-of-funnel traffic, yet tons of users were finding the app through specific Google searches. Lerner suggested programmatic SEO for their 300,000 trail maps. The CTO initially resisted: “They told me they thought of that. But the map rendering engine was slow. There was so much data, the pages just wouldn't load fast enough. So they nixed it.” Lerner proposed using static images with background map loading. They implemented this, leading to increased traffic and eventual acquisition. “It was more complicated than that, of course, but the point is, they crossed the idea off the list because they thought it was high effort. Instead, they focused on things that are easy, but wouldn't have a big impact.”

If you can’t put it on the back of an envelope with a pen and show me that an experiment at least has the potential to have a huge impact, then it’s just not worth the time.

To combat this kind of cognitive trap, Lerner recommends public accountability. “Have the team post growth experiments in Slack and get everyone to vote on which variant they think is going to be the winner,” he says. “Let the founder and the Head of Product and Head of Growth be very public about their bets, and then if they're wrong, let them be very public about not having all the answers. That’s quite empowering.”

Put growth in everyone’s job description

Another way to think about scaling growth more broadly is to give everyone ownership of growth. “Most companies are organized around skills or job functions, but growth isn’t a singular skill. It requires a lot of different skills,” Lerner says.

“Some of those teams are organized around job titles, which promotes inside-out thinking and internal competition,” he says. “Some teams are organized around customer segments, which is a great idea. But growth is everyone’s job. I mean literally everyone — operations, fulfillment, customer service, finance, HR.” Founders should be asking themselves: “How can we get every single person aligned to support our growth?"

He suggests a four-step process to achieve this:

- Share your North Star Metric with everyone in your company (e.g. weekly active users, meals delivered, gross merchandise volume, etc.). Take time to answer their questions and understand it.

- Ask (don't tell) each person to explain to you how their work impacts your North Star. “Have a little discussion about that, you should each learn something,” he says.

- Ask each person which work they could do, or do differently, to have the greatest positive impact on the North Star.

- Put that work into their quarterly goals.

Bring on the right people at the right time

Perhaps the most obvious way to scale growth at your company is to simply hire folks whose full-time job is to run these experiments. But before you add this function, Lerner says founders must be able to answer three questions:

- What's our first growth lever?

- How are we going to pull it?

- What's one way we can reliably get customers if we just double down?

Hopefully, after running hundreds of growth experiments on your own, you’ll develop a sense of what you’re good at and what’s still missing. “You’ll learn what muscles you already have and which ones you need to strengthen,” Lerner says.

This is the inflection point for building a dedicated growth team. “In other words, start hiring when you have your growth levers figured out, and you’re starting to wonder how to run experiments at scale,” he says.

There’s not one magical background that makes someone a good candidate for growth. But there are two reliable types of hires that Lerner recommends when you are just starting to build out a dedicated growth team:

- The Junior Generalist: In Lerner’s experience for hiring early growth people, there is a particular resume that stands out to him over the rest. “My first hires would be bright, junior generalists,” he says. “My best growth people I’ve ever hired had no product or marketing experience at all. They were analytical thinkers, former scientists who had a bias for action and good people skills.”

- The Internal Co-Pilot: Often your first growth people aren’t going to be “growth” people at all, but core members of your team who are already on board. “This could be anyone from the internal analyst to the customer service rep or product people or engineers that start naturally getting involved in some of the experiments you run. Get them started on one piece of the problem. They’ll grow and learn alongside you, and start to figure out the business. Hopefully, they’re going to advance into more senior roles.”

Wrapping up: Prioritizing growth will always pay off

Understanding the growth model, surfacing your growth levers, running experiments — all of this is a result of first adopting a founder-led growth mindset. Lerner emphasizes that doing this successfully requires intellectual honesty about what you don’t know. “The best founders, in terms of growth, have a really clear sense of the limits of their knowledge and what they need to figure out,” Lerner says.

With everything on your plate, it can be hard to make the argument to focus on growth yourself. But Lerner gives an interesting example: “You’d never hire someone else to be your head of product before you make your first product. Why do you think you’re going to hire someone off the street who can figure out your growth?” he says. “If you don’t know how to grow the product yourself, you’re not hiring someone to run growth, you’re hiring someone to figure it out. That’s a hard job, and people who can do it well are starting their own companies, not working for a teeny fraction of yours.”

He argues that growth is a founder’s job, partly because the process of discovering growth levers gives founders critical insights that inform every aspect of the business — by interviewing customers, identifying bottlenecks and running experiments, founders develop a deeper understanding of their company and the market that can’t be delegated. This knowledge circles back to inform everything from product to hiring decisions.

Hiring a Head of Growth sounds like a high-leverage move to figure these out. But you might already have the answers, and you might be the best person to uncover them.