Andrea Goulet and her business partner sat in her living room, casually reviewing their strategic plan, when an episode of This Old House came on television. It was one of those moments where ideas collide to create something new. They’d been looking for a way to communicate their value proposition — cleaning up legacy code and technical debt for other companies. And here they were, face to face with the perfect analogy.

“We realized that what we were doing transcended clearing out old code, we were actually remodeling software the way you would remodel a house to make it last longer, run better, do more,” says Goulet. “It got me thinking about how companies have to invest in mending their code to get more productivity. Just like you have to put a new roof on a house to make it more valuable. It’s not sexy, but it’s vital, and too many people are doing it wrong.”

Today, she’s CEO of Corgibytes — a consulting firm that re-architects and modernizes apps. She’s seen all varieties of broken systems, legacy code, and cases of technical debt so extreme it’s basically digital hoarding. Here, Goulet argues that startups need to shift their mindset away from paying down debt toward building technical wealth, and away from tearing down old code toward deliberately remodeling it. She explains this new approach, and how you can do the impossible — actually recruit amazing engineers to tackle this work.

RETHINKING LEGACY CODE

The most popular definition of legacy code comes from Michael Feathers, author of the aptly titled Working Effectively with Legacy Code: It's code without test coverage. That’s better than what most people assume — that the term only applies only to really old, archaic systems. But neither definition goes far enough, according to Goulet. “Legacy code has nothing to do with the age of the software. A two year-old app can already be in a legacy state,” she says. “It’s all about how difficult that software is to improve.”

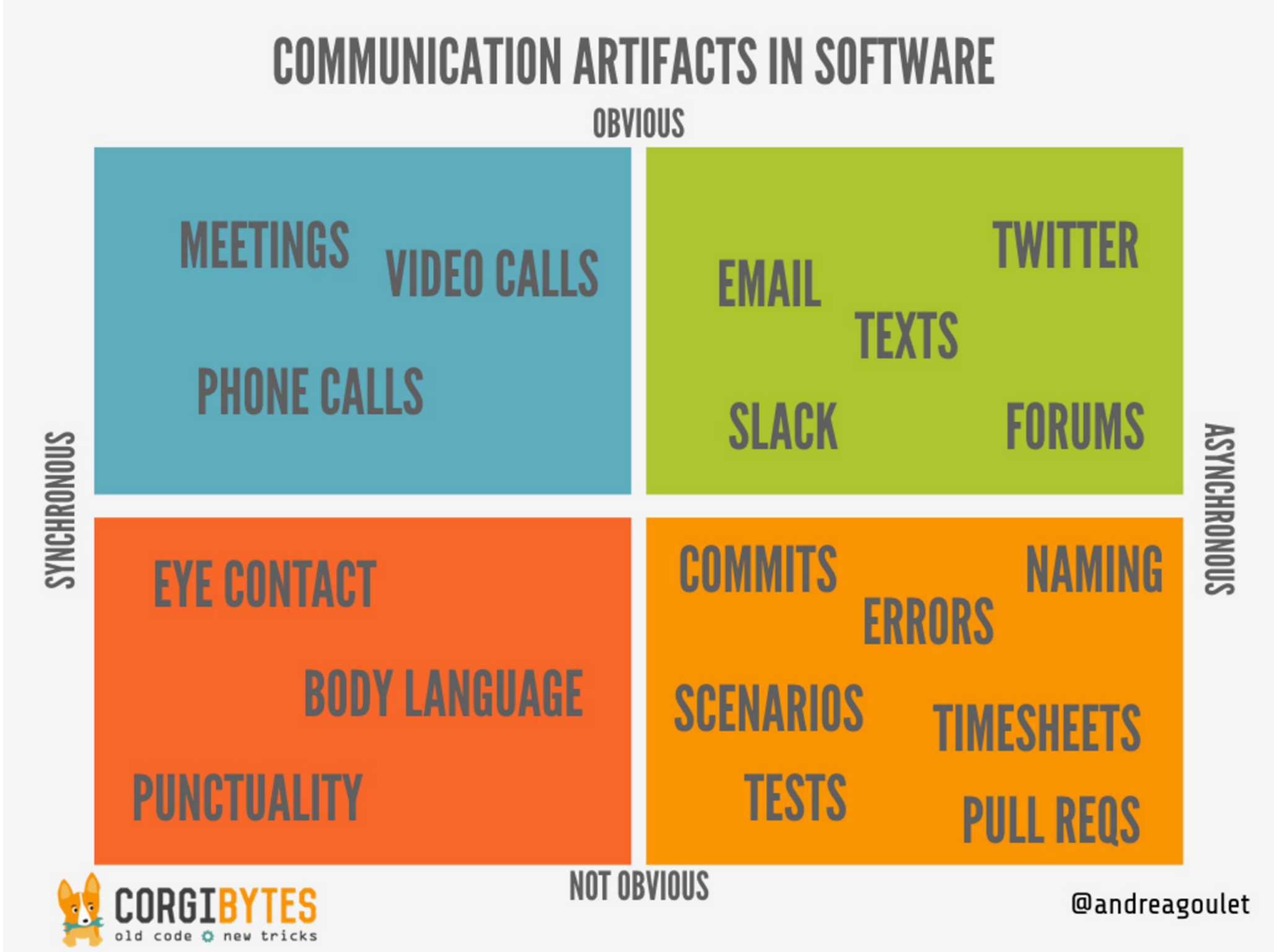

This means code that isn’t written cleanly, that lacks explanation, that contains zero artifacts of your ideas and decision-making processes. A unit test is one type of artifact, but so is any documentation of the rationale and reasoning used to create that code. If there’s no way to tell what the developer was thinking when you go to improve it — that’s legacy code.

Legacy code isn't a technical problem. It's a communication problem.

If you linger around in legacy code circles like Goulet does, you’ll find that one particular, and rather obscure adage dubbed Conway’s Law will make it’s way into nearly every conversation.

“It’s the law that says your codebase will mirror the communication structures across your organization,” Goulet says. “If you want to fix your legacy code, you can’t do it without also addressing operations, too. That’s the missing link that so many people miss.”

Goulet and her team dive into a legacy project much like an archaeologist would. They look for artifacts left behind that give them clues into what past developers were thinking. All of these artifacts together provide context to make new decisions.

The most important artifact? Well organized, intention-revealing, clean code. For example, if you name a variable with generic terms like “foo” or “bar,” you might come back six months later and have no idea what that variable is for.

If the code isn’t easy to read, a useful artifact is the source control system, because it provides a history of changes to the code and gives developers an opportunity to write about the changes they’re making.

“A friend of mine says that for commit messages, every summary should be the size of half a tweet, with the description as long as a blog post, if necessary,” says Goulet. “You have the chance to tightly couple your rationale with the code that’s being changed. It doesn’t take a lot of extra time and gives tons of information to people working on the project later, but surprisingly few people do it. It’s common to hear developers get so frustrated about working with a piece of code they run ‘git blame’ in a fit of rage to figure out who wrote that mess, only to find it was themselves.”

Automated tests are also fertile ground for rationale. “There’s a reason that so many people like Michael Feathers’ definition of legacy code,” Goulet explains. “Test suites, especially when used along with Behavior Driven Development practices like writing out scenarios, are incredibly useful tools for understanding a developer’s intention.”

The lesson here is simple: If you want to limit your legacy code down the line, pay attention to the details that will make it easier to understand and work with in the future. Write and run unit, acceptance, approval, and integration tests. Explain your commits. Make it easy for future you (and others) to read your mind.

That said, legacy code will happen no matter what. For reasons both obvious and unexpected.

Early on at a startup, there’s usually a heavy push to get features out the door. Developers are under enormous pressure to deliver, and testing falls by the wayside. The Corgibytes team has encountered many companies that simply couldn’t be bothered with testing as they grew — for years.

Sure, it might not make sense to test compulsively when you’re pushing toward a prototype. But once you have a product and users, you need to start investing in maintenance and incremental improvements. “Too many people say, ‘Don’t worry about the maintenance, the cool things are the features!’” says Goulet. “If you do this, you’re guaranteed to hit a point where you cannot scale. You cannot compete.”

As it turns out, the second law of thermodynamics applies to code too: You’ll always be hurtling toward entropy. You need to constantly battle the chaos of technical debt. And legacy code is simply one type of debt you’ll accrue over time.

“Again the house metaphor applies. You have to keep putting away dishes, vacuuming, taking out the trash,” she says. “if you don’t, it’s going to get harder, until eventually you have to call in the HazMat team.”

Corgibytes gets a lot of calls from CEOs like this one, who said: “Features used to take two weeks to push three years ago. Now they’re taking 12 weeks. My developers are super unproductive.”

Technical debt always reflects an operations problem.

A lot of CTOs will see the problem coming, but it’s hard to convince their colleagues that it’s worth spending money to fix what already exists. It seems like backtracking, with no exciting or new outputs. A lot of companies don’t move to address technical debt until it starts crippling day-to-day productivity, and by then it can be very expensive to pay down.

FORGET DEBT, BUILD TECHNICAL WEALTH

You’re much more likely to get your CEO, investors and other stakeholders on board if you reframe your technical debt as an opportunity to accumulate technical wealth — a term recently coined by agile development coach Declan Whelan.

“We need to stop thinking about debt as evil. Technical debt can be very useful when you’re in the early-stage trenches of designing and building your product,” says Goulet. “And when you resolve some debt, you’re giving yourself momentum. When you install new windows in your home, yes you’re spending a bunch of money, but then you save a hundred dollars a month on your electric bill. The same thing happens with code. Only instead of efficiency, you gain productivity that compounds over time.”

As soon as you see your team not being as productive, you want to identify the technical debt that's holding them back.

“I talk to so many startups that are killing themselves to acquire talent — they’re hiring so many high-paid engineers just to get more work done,” she says. “Instead, they should have looked at how to make each of their existing engineers more productive. What debt could you have paid off to get that extra productivity?”

If you change your perspective and focus on wealth building, you’ll end up with a productivity surplus, which can then be reinvested in fixing even more debt and legacy code in a virtuous cycle. Your product will be cruising and getting better all the time.

Stop thinking about your software as a project. Start thinking about it as a house you will live in for a long time.

This is a critical mindset shift, says Goulet. It will take you out of short-term thinking and make you care about maintenance more than you ever have.

Just like with a house, modernization and upkeep happens in two ways: small, superficial changes (“I bought a new rug!”) and big, costly investments that will pay off over time (“I guess we’ll replace the plumbing...”). You have to think about both to keep your product current and your team running smoothly.

This also requires budgeting ahead — if you don’t, those bigger purchases are going to hurt. Regular upkeep is the expected cost of home ownership. Shockingly, many companies don’t anticipate maintenance as the cost of doing business.

This is how Goulet coined the term ‘software remodeling.’ When something in your house breaks, you don’t bulldoze parts of it and rebuild from scratch. Likewise, when you have old, broken code, reaching for a re-write isn’t usually the best option.

Here are some of the things Corgibytes does when they’re called in to ‘remodel’ a codebase:

- Break monolithic apps into micro-services that are lighter weight and more easily maintained.

- Decouple features from each other to make them more extensible.

- Refresh branding and look and feel of the front-end.

- Establish automated testing so that code validates itself.

- Refactor, or edit, codebases to make them easier to work with.

Remodeling also gets into DevOps territory. For example, Corgibytes often introduces new clients to Docker, making it much easier and faster to set up new developer environments. When you have 30 engineers on your team, cutting the initial setup time from 10 hours to 10 minutes gives you massive leverage to accomplish more tasks. This type of effort can’t just be about the software itself, it also has to change how it’s built.

If you know which of these activities will make your code easier to handle and create efficiencies, you should build them into your annual or quarterly roadmap. Don’t expect them to happen on their own. But don’t put pressure on yourself to implement them all right away either. Goulet sees just as many startups hobbled by their obsession with having 100% test coverage from the very beginning.

To get more specific, there are three types of remodeling work every company should plan on:

- Automated testing

- Continuous delivery

- Cultural upgrades

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

Automated Testing

“One of our clients was going into their Series B and told us they couldn’t hire talent fast enough. We helped them introduce an automated testing framework, and it doubled the productivity of their team in under 3 months,” says Goulet. “They were able to go to their investors and say, ‘We’re getting more with a lean team than we would have if we’d doubled the team.'”

Automated testing is basically a combination of individual tests. You have unit tests which double-check single lines of code. You have integration tests that make sure different parts of the system are playing nice. And you have acceptance tests that ensure features are working as you envisioned. When you write these tests as automated scripts, you can essentially push a button and have your system validate itself rather than having to comb through and manually click through everything.

Instituting this before hitting product-market fit is probably premature. But as soon as you have a product you’re happy with, and that users who depend on it, it’s more than worth it to put this framework in place.

Continuous Delivery

This is the automation of delivery related tasks that used to be manual. The goal is to be able to deploy a small change as soon as it’s done and make the feedback loop as short as possible. This can give companies a big competitive advantage over their competition, especially in customer service.

“Let’s say every time you deploy, it’s this big gnarly mess. Entropy is out of control,” says Goulet. “We’ve seen deployments take 12 hours or more because it’s such a cluster. And when this happens, you’re not going to deploy as often. You’re going to postpone shipping features because it’s too painful. You’re going to fall behind and lose to the competition.”

Other tasks commonly automated during continuous improvement include:

- Checking for breaks in the build when commits are made.

- Rolling back in the event of a failure.

- Automated code reviews that check for code quality.

- Scaling computing resources up or down based on demand.

- Making it easy to set up development, testing, and production environments.

As a simple example, let’s say a customer sends in a bug report. The more efficient the developer is in fixing that bug and getting it out, the better. The challenge with bug fixes isn’t that making the change is all that difficult, it’s that the system isn’t set up well and the developer wastes a lot of time doing things other than solving problems, which is what they’re best at.

With continuous improvement, you would become ruthless about determining which tasks are best for the computer and which are best for the human. If a computer is better at it, you automate it. This leaves the developer gleefully solving challenging problems. Customers are happier because their complaints are addressed and fixed quickly. Your backlog of fixes narrows and you’re able to spend more time on new creative ways to improve your app even more. This is the kind of change that generates technical wealth. Because that developer can ship new code as soon as they fix a bug in one step, they have time and bandwidth to do so much more frequently.

“You have to constantly ask, ‘How can I improve this for my users? How can I make this better? How can I make this more efficient?’ But don’t stop there,” says Goulet. “As soon as you have answers to these questions, you have to ask yourself how you can automate that improvement or efficiency.”

Cultural Upgrades

Every day, Corgibytes sees the same problem: A startup that's built an environment that makes it impossible for its developers to be impactful. The CEO looms over their shoulders wondering why they aren’t shipping more often. And the truth is that the culture of the company is working against them. To empower your engineers, you have to look at their environment holistically.

To make this point, Goulet quotes author Robert Henri:

The object isn't to make art, it's to be in that wonderful state which makes art inevitable.

“That’s how you need to start thinking about your software,” she says. “Your culture can be that state. Your goal should always be to create an environment where art just happens, and that art is clean code, awesome customer service, happy developers, good product-market fit, profitability, etc. It’s all connected.”

This is a culture that prioritizes the resolution of technical debt and legacy code. That’s what will truly clear the path for your developers to make impact. And that’s what will give you the surplus to build cooler things in the future. You can’t remodel your product without making over the environment it’s developed in. Changing the overall attitude toward investing in maintenance and modernization is the place to start, ideally at the top with the CEO.

Here are some of Goulet's suggestions for establishing that flow-state culture:

- Resist the urge to reward “heroes” who work late nights. Praise effectiveness over effort.

- Get curious about collaboration techniques, such as Woody Zuill’s Mob Programming.

- Follow the four Modern Agile principles: make users awesome, experiment and learn rapidly, make safety a prerequisite, and deliver value continuously.

- Give developers time outside of projects each week for professional development.

- Practice daily shared journals as a way to enable your team to solve problems proactively.

- Put empathy at the center of everything you do. At Corgibytes, Brene Brown’s CourageWorks training has been invaluable.

If execs and investors balk at this upgrade, frame it in terms of customer service, Goulet says. Tell them how the end product of this change will be a better experience for the people who matter most to them. It’s the most compelling argument you can make.

FINDING THE MOST TALENTED REMODELERS

It’s an industry-wide assumption that badass engineers don’t want to work on legacy code. They want to build slick new features. Sticking them in the maintenance department would be a waste, people say.

These are misconceptions. You can find incredibly skilled engineers to work on your thorniest debt if you know where and how to look — and how to make them happy when you’ve got them.

“Whenever we speak at conferences, we poll the audience and ask 'Who loves working on legacy code?' It's pretty consistent that less than 10% of any crowd will raise their hands.” says Goulet. “But when I talked to these people, I found out they were the engineers who liked the most challenging problems.”

She has clients coming to her with homegrown databases, zero documentation, and no conceivable way to parse out structure. This is the bread and butter of a class of engineers she calls “menders.” Now she has a team of them working for her at Corgibytes who like nothing more than diving into binary files to see what’s really going on.

So, how can you find these elite forces? Goulet has tried a lot of things — and a few have worked wonders.

She launched a community website at legacycode.rocks that touts the following manifesto: “For too long, those of us who enjoy refactoring legacy code have been treated as second class developers... If you’re proud to work on legacy code, welcome!”

“I started getting all these emails from people saying, ‘Oh my god, me too!’” she says. “Just getting out there and spreading this message about how valuable this work is drew in the right people.”

She’s also used continuous delivery practices in her recruiting to give these type of developers what they want: Loads of detail and explicit instructions. “It started because I hated repeating myself. If I got more than a few emails asking the same question, I’d put it up on the website, much like I would if I was writing documentation.”

But over time, she noticed that she could refine the application process even further to help her identify good candidates earlier in the process. For example, her application instructions read, “The CEO is going to review your resume, so make sure to address your cover letter to the CEO” without providing a gender. All letters starting with “Dear Sir,” or "Mr." are immediately trashed. And this is just the beginning of her recruiting gauntlet.

“This started because I was annoyed at how many times people assumed that because I’m the CEO of a software company, I must be a man,” Goulet said. “So one day, I thought I’d put it on the website as an instruction for applicants to see who was paying attention. To my surprise, it didn’t just muffle the less serious candidates. It amplified the folks who had the particular skills for working with legacy code.”

Goulet recalls how one candidate emailed her to say, “I inspected the code on your website (I like the site and hey, it’s what I do). There’s a weird artifact that seems to be written in PHP but it appears you’re running Jekyll which is in Ruby. I was really curious what that’s about.”

It turned out that there was a leftover PHP class name in the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript that Goulet got from her designer that she’d been meaning to getting around to but hadn’t had a chance. Her response: “Are you looking for a job?”

Another candidate noticed that she had used the term CTO in an instruction, but that title didn’t exist on her team (her business partner is the Chief Code Whisperer). Again, the attention to detail, the curiosity, and the initiative to make it better caught her eye.

Menders aren't just detail-oriented, they're compelled by attention to detail.

Surprisingly, Goulet hasn't been plagued with the recruiting challenges of most tech companies. “Most people apply directly through our website, but when we want to cast a wider net, we use PowerToFly and WeWorkRemotely. I really don’t have a need for recruiters at the moment. They have a tough time understanding the nuance of what makes menders different.”

If they make it through an initial round, Goulet has a candidate read an article called “Naming is a Process” by Arlo Belshee. It delves into the very granular specifics of working with indebted code. Her only directions: “Read it and tell me what you think.”

She’s looking for understanding of subtleties in their responses, and also the willingness to take a point of view. It’s been really helpful in separating deep thinkers with conviction from candidates who just want to get hired. She highly recommends choosing a piece of writing that matters to your operations and will demonstrate how passionate, opinionated, and analytical people are.

Lastly, she’ll have a current team member pair program with the candidate using Exercism.io. It’s an open-source project that allows developers to learn how to code in different languages with a range of test driven development exercises. The first part of the pair programming session allows the candidate to choose a language to build in. For the next exercise, the interviewer gets to pick the language. They get to see how the person deals with surprise, how flexible they are, and whether they’re willing to admit they don’t know something.

“When someone has truly transitioned from a practitioner to a master, they freely admit what they don’t know,” says Goulet.

Having someone code in a language they aren’t that familiar with also gauges their stick-to-it-iveness. “We want someone who will say, ‘I’m going to hammer on this problem until it’s done.’ Maybe they’ll even come to us the next day and say, ‘I kept at it until I figured it out.’ That’s the type of behavior that’s very indicative of success as a mender.”

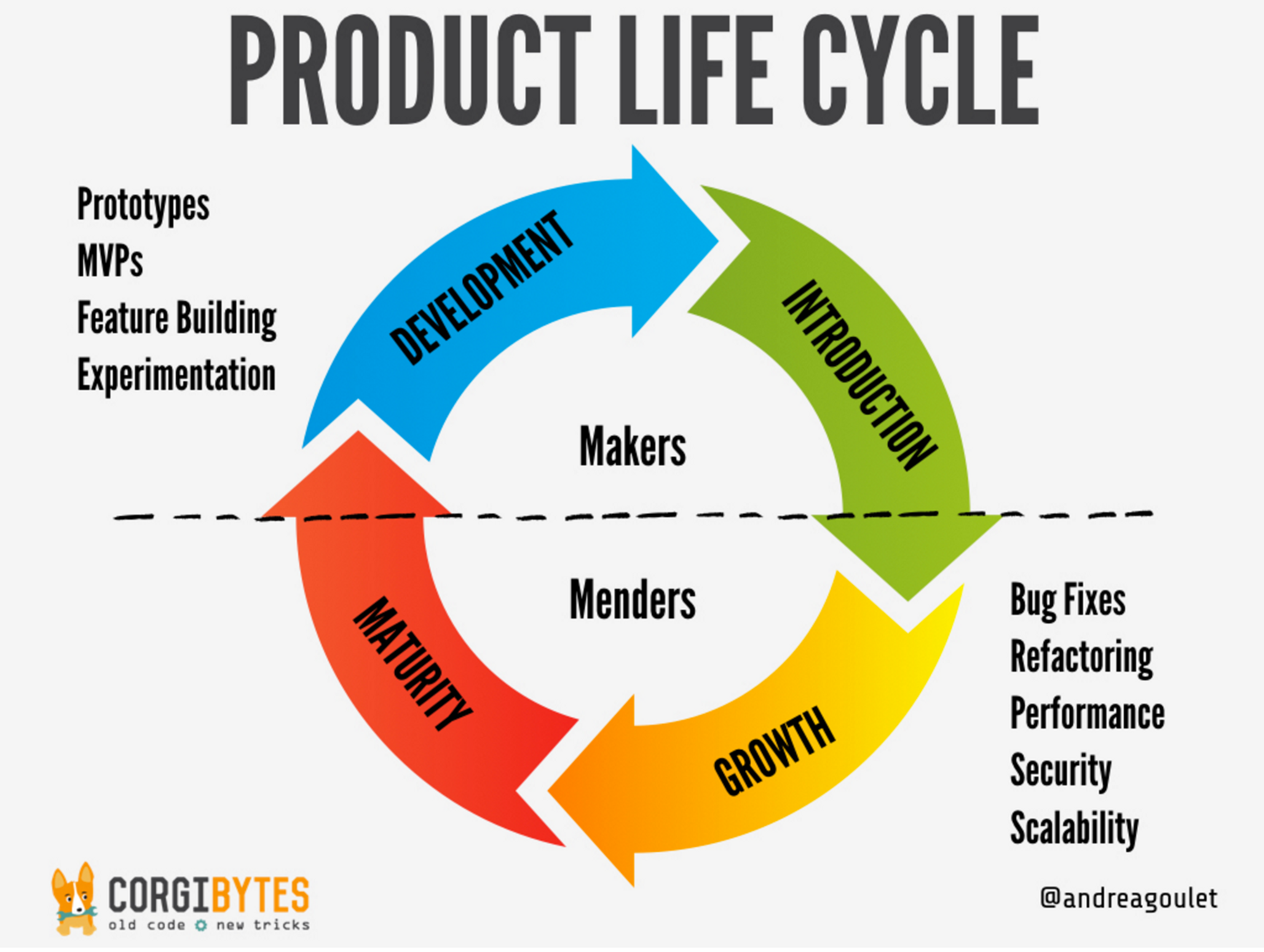

Makers are so lionized in our industry that everyone wants to have them do maintenance too. That's a mistake. The best menders are never the best makers.

Once she has talented menders in the door, Goulet knows how to set them up for success. Here’s what you can do to make this type of developer happy and productive:

- Give them a generous amount of autonomy. Hand them assignments where you explain the problem, sure, but never dictate how they should solve it.

- If they ask for upgrades to their computers and tooling, do it. They know what they need to maximize efficiency.

- Help them limit their context-switching. They like to focus until something’s done.

Altogether, this approach has helped Corgibytes build a waiting list of over 20 qualified developers passionate about legacy code.

STABILITY IS NOT A DIRTY WORD

Most startups don’t think past their growth phase. Some may even believe growth should never end. And it doesn’t have to, even when you enter the next stage: Stability. All stability means is that you have the people and processes you need to build technical wealth and spend it on the right priorities.

“There’s this inflection point between growth and stability where menders must surge, and you start to balance them more equally against the makers focused on new features,” says Goulet. “You have your systems. Now you need them to work better.”

This means allocating more of your organization’s budget to maintenance and modernization. “You can’t afford to think of maintenance as just another line item,” she says. “It has to become innate to your culture — something important that will yield greater success in the future.”

Ultimately, the technical wealth you build with these efforts will give rise to a whole new class of developers on your team: scouts that have the time and resources to explore new territory, customer bases and opportunities. When you have the bandwidth to tap into new markets and continuously get better at what you already do — that’s when you’re truly thriving.