A psychology study at UC Berkeley broke students into groups of three, with one person chosen to be the leader of a project. At some point, the researchers would bring in a plate of four cookies.

"We all know the social norm is not to take the last cookie," says Robert Sutton, management expert at Stanford's School of Engineering. "But the research showed consistently that the person in power would take that fourth cookie. They even tended to eat with their mouths open and leave more crumbs. And this is just in the laboratory. Imagine that you're a CEO and everywhere you go you're empowered, and everyone is kissing your ass. You can start to see why it's so hard to be good."

Made famous by his 2005 book The No Asshole Rule, Sutton has spent hours studying the moves made by technology's top leaders, including Steve Jobs, Andy Grove, and others. More recently, though, he's turned his attention from negative qualities to what the best bosses in the world do and understand. A lot of it has to do with an innate sense of human emotions, but the good news is management can be learned.

In this Stanford Entrepreneurship Corner Talk, he breaks down what it takes to become a great boss — which, as it turns out, makes a much bigger difference than you might think.

It Really Is All About You

Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric and one of the most celebrated business leaders in history said, “When you’re a boss, it’s not all about you.” But Sutton disagrees. “This is only half true,” he says. “When you look at what happens to people when they're put into a position of authority, in many ways things really do become all about them.”

First, there’s something called the “magnification effect.” When you’re in power, suddenly everyone starts watching what you do very closely. At the same time, you start getting more credit and more blame than you deserve for organizational performance. When outcomes are dissected, it turns out that leaders are responsible for about 15% of what actually happens, but they get about 50% of the blame or credit.

For both of these reasons, the best bosses make being perceptive one of their core job responsibilities. This is easy to say but hard to execute.

Sutton cites a story he heard about a wave of 2009 downsizing. At an unnamed company, a secretary walked up to an executive vice president and simply asked, “When are the layoffs coming?” The EVP was shocked, even though cuts were secretly planned. How did she know? The tell was that he was shuffling around the office staring at his shoes all day, unable to look anyone in the eye. With the context of brewing financial trouble, his employees knew exactly what was happening and had already started to panic.

“Another thing that makes it difficult for leaders to be in-tune with their people is what I call ‘power poisoning,’” Sutton says. “When you put human beings in power, three things happen pretty reliably: They focus more on their own needs and concerns; they focus less on the needs and concerns of others; and they act like the rules don’t apply to them." There’s even evidence that when a company is performing great, leaders become more clueless, self-absorbed, etc. Thus the Berkeley cookie study.

When you become successful is when you should be especially wary you're going to turn into an idiot. There's a lot of evidence to support that.

The Hallmarks of Great Bosses

Unless you happen to be extremely empathetic, being a good manager requires a tactical approach. This is where Sutton’s hoards of data come in handy. He’s talked to enough people to know what workers actually want in a boss — not just what they say they want.

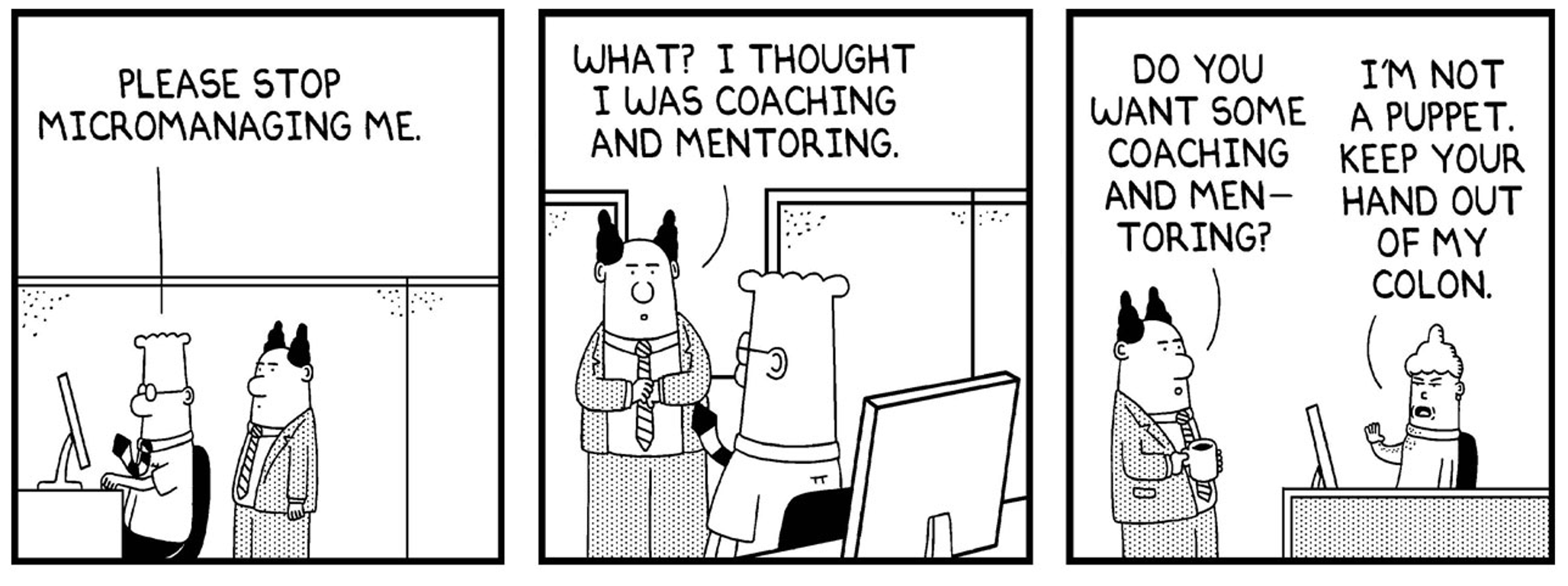

Be perfectly assertive. Even more important than having charisma, knowing exactly when to be aggressive and when to be passive elicits the best results. “The best bosses have an ability to turn up the volume, to be pushy, and to get in people’s faces when they need it — maybe even give them some negative feedback,” Sutton says. “But they also know when it’s the right time to back off.”

This becomes especially critical if you’re supervising creative work. In this arena, micromanagement becomes anathema. “When you watch people closely, when you ask them more questions and constantly evaluate them — that stifles creativity. Ironically, this is how most people in Silicon Valley seem to act as bosses.”

What can you do instead? He points to IDEO founder David Kelley as a prime example of a light-touch manager. “David is a master of what I call ‘management by walking out of the room.’” He might convene a meeting, but if things are going well and the conversation is productive, he’ll eventually walk out. “He knows the fact that he is an authority figure can mess things up. The discussion can be more creative without him there.”

After you plant a seed in the ground, you don't dig it up every week to see how it's doing.

This is a quote from William Coyne, who led R&D at 3M for over a decade. Sutton loves this saying because it busts the myth that the more bosses get in people’s faces, the better they're going to do.

“So, on one hand, we want bosses to lead us who are confident and competent, who act like they are in charge and who make firm decisions. But on the other, we don’t want to work for arrogant, pigheaded bastards who can’t take any input.”

What you end up with is the challenge to walk the line between the two. This requires cultivating what Sutton calls an “attitude of wisdom.” “Andy Grove summarized this attitude pretty well. It's the courage and confidence to act on what you know right now, along with the humility to course correct when new information comes along."

This all sounds very meta — maybe even impossible. But Sutton has five rules for managers to help them walk this tightrope:

1) Listen. It’s not just about hearing your employees. It’s more about getting them to tell you the truth when there’s very little incentive. Study after study shows that flattery makes people like you more, even if they know you’re lying. Even more research shows that people are less liked when they share negative news or criticism. Given these conditions, why would you ever tell your boss the truth? And when this is the case, things can get pretty out of whack.

According to Sutton, when Richard Feynman was recruited to the commission looking into the Challenger space shuttle disaster, he would ask people at NASA, “What is the probability that the main engine of the shuttle would fail?” This was something that had yet to happen, so the question was hypothetical. The engineers at the bottom of the food chain estimated the odds to be one in 200. The senior executives pegged it at one in 100,000. “I love this,” Sutton says. “It shows how out of touch our leaders can be, how much ass-kissing goes on, and how difficult it is to break bad news.”

To be a good leader, then, requires creating safe spaces for the truth to flourish, downplaying punishment for failure, and committing to listening to what everyone has to say.

2) Fight constructively. “There's a lot of evidence, especially for creative work, that the most effective teams fight in an atmosphere of mutual respect,” Sutton says. He quotes American organizational theorist Karl Weick:

Fight as if you're right. Listen as if you're wrong.

All good teams find a way to do this. Brad Bird, the Pixar director who brought The Incredibles and Ratatouille to life, was famous for creating constructive conflict. But Pixar wanted to shake things up, so they gave him a chance and his own team. When recruiting, Sutton says Bird asked for all the black sheep. “Give me all the people who are ready to leave — the ones who have new ways to solve problems and are desperate to try them,” he said. The crew drove each other nuts fighting, but in what everyone described as a “loving” atmosphere rooted in respect for each other’s work.

As a boss, crafting this atmosphere is vital. But it has an arc to it too. Early on, you need to contain fights and encourage free idea generation. “Don’t start shooting things down until you have enough choices,” Sutton says. And then, when things are finally being decided, you need to convince people to accept defeat gracefully so they can work to implement ideas they disagreed with. “As Andy Grove argued, if you disagree with an idea, you should work especially hard to implement it. That way, when it fails, you know it was because it was a bad idea, not a bad implementation.” Conveying these ideas to your team can have real impact.

3) Adopt a “small win” strategy. Jim Collins, author of the well-known business title Good to Great, touts the virtues of going after “big hairy goals.” But a great leader, according to Sutton, is able to break these goals into bite-size pieces that keep people motivated and moving. Otherwise, a team can get stuck.

He gives the example of a CEO who found herself staring down massive layoffs unless she figured out how to bump sales by 25% over the previous year — a goliath and unlikely task. Instead of giving up, she gathered her top execs and pads of Post-It notes. Then she said, “I want us to write down all the steps we need to take to run a successful sales campaign.”

Soon, they had over 100 stickies-worth of ideas. The CEO drew a line down the center of a whiteboard and instructed her team to put all the easy tasks on one side and all the hard tasks on the other. “Now, let’s start talking about how we accomplish all these easy ones in the next two weeks,” she said. That’s exactly what they did.

“By doing this, they got all the small wins they needed to get the ball rolling,” Sutton explains. “And after that, they had the confidence to be successful when they tackled the more difficult things. A great CEO makes people feel the mission and then makes the implementation easy. You need that one-two punch.”

4) Don’t be too sensitive. When you manage other people, you inherently have the right to offer them feedback. Good bosses will also be able to receive feedback, even if it’s not phrased as delicately as it could be. “You’ve got to be real careful about snapping people’s heads off,” Sutton says. “If someone comes to you with criticism, you have to always stop and consider whether you’re being insensitive or an egotistical jerk that can’t take bad news.”

5) Nip disrespect in the bud. While you should always check to make sure you’re not being too touchy, as a manager you need to know when to shut down feedback that isn’t constructive. Sutton mentions a study here by Charles O’Reilly, a professor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. Data he collected showed that the best leaders of teams in a sales environment were the people who wouldn’t let their subordinates get away with bad behavior, including disrespecting each other or customers. “They would move very quickly to give feedback,” Sutton says. “There’s an argument that the worst bosses are the ones who let things fester and think they’ll naturally get better on their own. They usually don’t.”

In addition to these five cardinal rules, Sutton says there are two categories of employees to keep your eyes on: super stars and rotten apples. To be a good boss for everyone, these individuals need to be managed in very careful, specific ways.

Super stars aren’t always an absolute positive. In fact, Sutton believes that most companies over-incentivize high performers, creating huge, unreasonable spreads in pay that can only come back to bite you. More importantly, though, you need to be sure about how you define your super stars. If you look closely, most great companies — like Google, or IDEO or General Electric — define their super stars as those who get ahead by helping others succeed, not by stomping on people on their way to the top. “It’s one of those things you see over and over again when you dig into the reward systems at great companies,” he says.

But this can also be a gray area. Men’s Warehouse is a particularly interesting example. The suit-seller is very vocal about having a team-based culture, even though pay is driven by commission. “The idea is that people come to Men’s Warehouse to get in and out with a great suit as fast as possible, so you want every salesperson in the store cooperating to make sales,” says Sutton. “They had one guy in the Seattle store who was consistently the highest-performing salesperson over and over again. But he wouldn’t help his teammates with sales. He would even steal sales from them. So they fired him. And the interesting thing that happened was that sales in that store went up by more than 30%, even though no other salesperson reached his level of performance.”

The moral is, you need to know who your real stars are, and create an environment where they're set up for success.

Rotten apples are a bit more straightforward. Everyone knows that negative people are damaging to company culture, but they probably don’t know exactly how damaging. There’s an accepted rule that says if you have a relationship with someone, either personal or professional, you need at least five positive interactions for every one negative interaction to keep that relationship healthy.

In the workplace, when you have a bad encounter with someone, it packs five times more emotional wallop than a positive encounter.

There’s research that shows that when teams have just one rotten apple — someone who is lazy or depressive or uncooperative — it knocks down team performance by up to 30 to 40%. “It’s contagious,” Sutton says. “If you work with jerks, you start acting like them. That’s one problem. And then on top of that, rotten apples are high-maintenance. You end up spending more time dealing with this one person than doing the job.”

While there is evidence that motivated bad apples can be coached and improved, there comes a point where you have to get rid of them. And the rule of thumb is the earlier the better. This is where Sutton’s famous “no asshole rule” comes in. He’s even seen it put into practice to great effect. After his book came out, he noticed a company called Baird at No. 39 on FORTUNE magazine’s list of best places to work. The company said their culture was defined by having a strict “no asshole rule.” Of course, Sutton got on the phone with the CEO, Paul Purcell, to see how he had deployed the rule.

Purcell’s response floored him: “During interviews, I tell candidates that if I discover they’re an asshole, I’ll fire them and see how they react.” When Sutton asked him for his definition of asshole, Purcell said, “Somebody who consistently puts their own needs ahead of their peers, customers or the company.”

On the flip-side of the equation, if you’re trying to determine whether the prospective manager you’re interviewing with is a rotten apple, you can tune in to how often they use the pronoun “I” instead of “we.” Does it sound like they take an inordinate amount of credit for the projects other people have been talking about?

Basically, if you want to be a great boss (or work for one), you have to make it clear that there is no room for selfishness on your team or in your organization. Even if you have someone incredibly productive onboard, selfishness will always be an opportunity cost.

How to Know If You Lead Like a Boss

While there’s no magical advice that can turn you into a stellar founder or CEO, there’s one litmus test Sutton recommends for managers to determine whether they are good at their jobs.

After people talk to you, do they come away with more or less energy?

This is something you can ask members of your team, or simply observe in many cases. It’s a simple “yes” or “no.” Management Professor Rob Cross at the University of Virginia has conducted surveys at upward of 50 companies, and he finds over and over again that this question is one of the strongest predictors of whether or not people get promoted or fired.

Being an energizing force is even more important at companies focused on rapid innovation. In Silicon Valley, it can make the difference between getting the right team, funding, and resources you need to scale or never getting off the ground.

Click here to watch the original video of Bob Sutton's Stanford Entrepreneurship Corner talk.